As the chief designer assigned to the “thin-clam” team at Motorola, Chris Arnholt was responsible for some of the phone’s distinctive physical features, including its sleek aluminum finish and backlit keyboard. In fact, it was he who pushed the company’s engineers and marketers to buck an industry trend toward phones that were getting fatter because of many add-ons such as cameras and stereo speakers. For Arnholt had a vision. He called it “rich minimalism,” and his goal was to help the Motorola cell phone team realize a product that embodied that profile.

But what exactly did Arnholt mean by rich minimalism? “Sometimes,” he admits, “my ideas are tough to communicate,” but as a veteran in his field, he also understands that “design is really about communication.”See Adam Lashinsky, “RAZR’s Edge,” Fortune, CNNMoney.com, June 1, 2006, http://money.cnn.com/magazines/fortune/fortune_archive/2006/06/12/8379239/index.htm (accessed August 22, 2008); Scott D. Anthony, “Motorola’s Bet on the RAZR’s Edge,” HBS Working Knowledge, September 12, 2005, http://hbswk.hbs.edu/archive/4992.html (accessed August 24, 2008). His chief (and ongoing) task, then, was communicating to the cell phone team what he meant by rich minimalism. Ultimately, of course, he had to show them what rich minimalism looked like when it appeared in tangible form in a fashionable new cell phone. In the process, he also had to be sure that the cell phone included certain key benefits that prospective consumers would want. As always, the physical design of the finished product had to be right for its intended market.

We’ll have much more to say about the process of developing new products in Chapter 10 "Product Design and Development". Here, however, let’s simply highlight two points about the way successful companies approach the challenges of new-product design and development (which you will likely recognize from reading the first part of this chapter):

The common denominator in both facets of the process is effective communication. The designer, for example, must communicate not only his vision of the product but also certain specifications for turning it into something concrete. Chris Arnholt sculpted models out of cornstarch and then took them home at night to refashion them according to suggestions made by the product team. Then he’d put his newest ideas on paper and hand the drawings over to another member of his design team, who’d turn them into 3D computer graphics from which other specialists would build plastic models. Without effective communication at every step in this process, it isn’t likely that a group of people with different skills would produce plastic models bearing a practical resemblance to Arnholt’s original drawings. On top of everything else, Arnholt’s responsibility as chief designer required him to communicate his ideas not only about the product’s visual and physical features but also about the production processes and manufacturing requirements for building it.See Industrial Designers Society of America (IDSA), “About ID,” IDSA, http://www.idsa.org/absolutenm/templates/?a=89&z=23 (accessed September 4, 2008).

Thus Arnholt’s job—which is to say, his responsibility on the cell phone team—meant that he had to do a lot more than merely design the product. Strictly speaking, the designer’s function is to understand a product from the consumer’s point of view; develop this understanding into a set of ideas and specifications that will satisfy not only consumer needs but producer requirements; and make recommendations through drawings, models, and verbal communications.IDSA, Industrial Designers Society of America (IDSA), “About ID,” IDSA, http://www.idsa.org/absolutenm/templates/?a=89&z=23 (accessed September 4, 2008). Even our condensed version of the RAZR story, however, indicates that Arnholt’s job was far broader. Why? Because new-product design is an integrative process: contributions must come from all functions within an organization, including operations (which includes research and development, engineering and manufacturing), marketing, management, finance, and accounting.See Glen L. Urban and John R. Hauser, Design and Marketing of New Products, 2nd ed. (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1993), 173.

Our version of the RAZR story has emphasized operations (which includes research and development, engineering, and manufacturing) and touched on the role of marketing (which collects data about consumer needs). Remember, though, that members from several areas of management were recruited for the team. Because the project required considerable investment of Motorola’s capital, finance was certainly involved, and the decision to increase production in late 2004 was based on numbers crunched by the accounting department. At every step, Arnholt’s drawings, specs, and recommendations reflected his collaboration with people from all these functional areas.

As we’ll see in the next section, what all this interactivity amounts to is communication.See Glen L. Urban and John R. Hauser, Design and Marketing of New Products, 2nd ed. (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1993), 653. As for what Arnholt meant by rich minimalism, you’ll need to take a look at the picture of the RAZR in Figure 8.1 "Motorola RAZR". Among other things, it means a blue electroluminescent panel and a 22 kHz polyphonic speaker.

Let’s start with a basic (and quite practical) definition of communicationProcess of transferring information from a sender to a receiver. as the process of transferring information from a sender to a receiver. When you call up a classmate to inform him that your Introduction to Financial Accounting class has been canceled, you’re sending information and your classmate is receiving it. When you go to your professor’s Web site to find out the assignment for the next class, your professor is sending information and you’re receiving it. When your boss e-mails you the data you need to complete a sales report and tells you to e-mail the report back to her by 4 o’clock, your boss is sending information and, once again, you’re receiving it; later in the day, the situation will be reversed.

Obviously, you participate in dozens of “informational transfers” every day. (In fact, they take up about 70 percent of your waking hours—80 percent if you have some sort of managerial position.Stephen P. Robbins and Timothy A. Judge, Organizational Behavior, 13th ed. (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, 2009), 368; David A. Whetten and Kim S. Cameron, Developing Management Skills, 7th ed. (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, 2007), 243.) In any case, it wouldn’t make much sense for us to pursue the topic much further without assuming that you’ve gained some experience and mastered some skills in the task of communicating. At the same time, though, we’ll also venture to guess that you’re much more comfortable having casual conversations with friends than writing class assignments or giving speeches in front of classmates. That’s why we’re going to resort to the same plain terms that we used when we discussed the likelihood of your needing teamwork skills in an organizational setting: The question is not whether you’ll need communication skills (both written and verbal). You will. The question is whether you’ll develop the skills to communicate effectively in a variety of organizational situations.

Once again, the numbers back us up. In a recent survey by the Association of Colleges and Employers, the ability to communicate well topped the list of skills that business recruiters want in potential hires.National Association of Colleges and Employers, “2006 Job Outlook,” NACEWeb, 2007, http://www.naceweb.org (accessed August 12, 2008). A College Board survey of 120 major U.S. companies concludes that writing is a “threshold skill” for both employment and promotion. “In most cases,” volunteered one human resources director, “writing ability could be your ticket in—or your ticket out.” Applicants and employees who can’t write and communicate clearly, says the final report, “will not be hired and are unlikely to last long enough to be considered for promotion.”College Board, “Writing: A Ticket to Work…or a Ticket Out: A Survey of Business Leaders,” Report of the National Commission on Writing, September 2004, http://www.writingcommission.org/prod_downloads/writingcom/writing-ticket-to-work.pdf (accessed August 10, 2008).

They’re important to you because they’re important to prospective employers. And why do employers consider communication skills so important? Because they’re good for business. Research shows that businesses benefit in several ways when they’re able to foster effective communication among employees:John V. Thill and Courtland L. Bovée, Excellence in Business Communication, 8th ed. (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, 2008), 4. See Nicholas Carr, “Lessons in Corporate Blogging,” Business Week, July 18, 2006, 9.

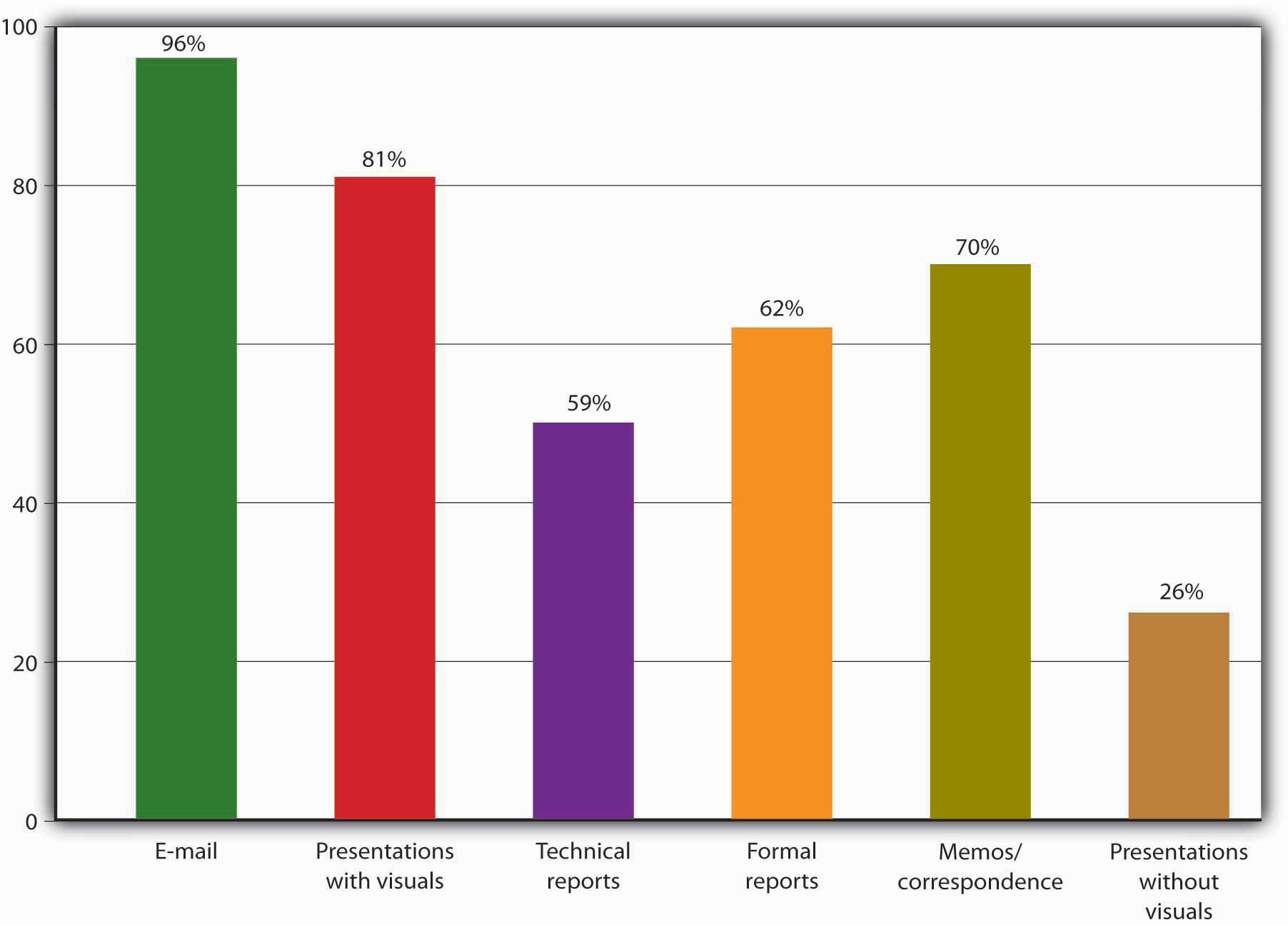

Figure 8.7 "Required Skills" reveals some further findings of the College Board survey that we mentioned above—namely, the percentage of companies that identified certain communication skills as being “frequently” or “almost always” necessary in their workplaces. As you can see, ability in using e-mail is a nearly universal requirement (and in many cases this includes the ability to adapt messages to different receivers or compose persuasive messages when necessary). The ability to make presentations (with visuals) also ranks highly.

Figure 8.7 Required Skills

Effective communication is needed in several facets of the new-product design and development process:

Businesses benefit in several ways when they’re able to foster effective communication among employees:

(AACSB) Analysis

Pick a company you’re interested in working for when you graduate from college. For this company, identify:

For each of these positions, describe the skills needed to get the job and those needed to be successful in the position.