So far, we’ve focused our attention on the financial environment in which U.S. businesses operate. Now let’s focus on the role that finance plays within an organization. In Chapter 1 "The Foundations of Business", we defined finance as all the activities involved in planning for, obtaining, and managing a company’s funds. We also explained that a financial manager determines how much money the company needs, how and where it will get the necessary funds, and how and when it will repay the money that it has borrowed. The financial manager also decides what the company should do with its funds—what investments should be made in plant and equipment, how much should be spent on research and development, and how excess funds should be invested.

Because new businesses usually need to borrow money in order to get off the ground, good financial management is particularly important to start-ups. Let’s suppose that you’re about to start up a company that you intend to run from your dorm room. You thought of the idea while rummaging through a pile of previously worn clothes to find something that wasn’t about to get up and walk to the laundry all by itself. “Wouldn’t it be great,” you thought, “if there was an on-campus laundry service that would come and pick up my dirty clothes and bring them back to me washed and folded.” Because you were also in the habit of running out of cash at inopportune times, you were highly motivated to start some sort of money-making enterprise, and the laundry service seemed to fit the bill (even though washing and folding clothes wasn’t among your favorite activities—or skills).

Because you didn’t want your business to be so small that it stayed under the radar of fellow students and potential customers, you knew that you’d need to raise funds to get started. So what are your cash needs? To answer this question, you need to draw up a financial planPlanning document that shows the amount of funds a company needs and details a strategy for getting those funds.—a document that performs two functions:

Fortunately, you can draw on your newly acquired accounting skills to prepare the first section—the one in which you’ll specify the amount of cash you need. You start by estimating your sales (or, in your case, revenue from laundering clothes) for your first year of operations. This is the most important estimate you’ll make: without a realistic sales estimate, you can’t accurately calculate equipment needs and other costs. To predict sales, you’ll need to estimate two figures:

You calculate as follows: You estimate that 5 percent of the ten thousand students on campus will use the service. These five hundred students will have one large load of laundry for each of the thirty-five weeks that they’re on campus. Therefore, you’ll do 17,500 loads (500 × 35 = 17,500 loads). You decide to price each load at $10. At first, this seemed high, but when you consider that you’ll have to pick up, wash, dry, fold, and return large loads, it seems reasonable.

Perhaps more important, when you projected your costs—including salaries (for some student workers), rent, utilities, depreciation on equipment and a truck, supplies, maintenance, insurance, and advertising—you found that each load would cost $8, leaving a profit of $2 per load and earning you $35,000 for your first year (which is worth your time, though not enough to make you rich).

What things will you have to buy in order to get started? Using your estimate of sales, you’ve determined that you’d need the following:

And, you’ll need cash—cash to carry you over while the business gets going and cash with which to pay your bills. Finally, you’d better have some extra money for contingencies—things you don’t expect, such as a machine overflowing and damaging the floor. You’re mildly surprised to find that your cash needs total $33,000. Your next task is to find out where you can get $33,000. In the next section, we’ll look at some options.

Figure 13.8 "Where Small Businesses Get Funding" summarizes the results of a survey in which owners of small and medium-size businesses were asked where they typically acquired their financing. To simplify matters, we’ll work on the principle that new businesses are generally financed with some combination of the following:

Figure 13.8 Where Small Businesses Get Funding

Remember that during its start-up period, a business needs a lot of cash: not only will it incur substantial start-up costs, but it may even suffer initial operational losses.

Its owners are the most important source of funds for any new business. Figuring that owners with substantial investments will work harder to make the enterprise succeed, lenders expect owners to put up a substantial amount of the start-up money. Where does this money come from? Usually through personal savings, credit cards, home mortgages, or the sale of personal assets.

For many entrepreneurs, the next stop is family and friends. If you have an idea with commercial potential, you might be able to get family members and friends either to invest in it (as part owners) or to lend you some money. Remember that family and friends are like any other creditors: they expect to be repaid, and they expect to earn interest. Even when you’re borrowing from family members or friends, you should draw up a formal loan agreement stating when the loan will be repaid and specifying the interest rate.

The financing package for a start-up company will probably include bank loans. Banks, however, will lend you some start-up money only if they’re convinced that your idea is commercially feasible. They also prefer you to have some combination of talent and experience to run the company successfully. Bankers want to see a well-developed business plan, with detailed financial projections demonstrating your ability to repay loans. Financial institutions offer various types of loans with different payback periods. Most, however, have a few common characteristics.

The period for which a bank loan is issued is called its maturityPeriod of time for which a bank loan is issued.. A short-term loanLoan issued with a maturity date of less than one year. is for less than a year, an intermediate loanLoan issued with a maturity date of one to five years. for one to five years, and a long-term loanLoan issued with a maturity date of five years or more. for five years or more. Banks can also issue lines of creditCommitment by a bank that allows a company to borrow up to a specified amount of money as the need arises. that allow you to borrow up to a specified amount as the need arises (it’s a lot like the limit on your credit card).

In taking out a loan, you want to match its term with its purpose. If, for example, you’re borrowing money to buy a truck that you plan to use for five years, you’d request a five-year loan. On the other hand, if you’re financing a piece of equipment that you’ll use for ten years, you’ll want a ten-year loan. For short-term needs, like buying inventory, you may request a one-year loan.

With any loan, however, you must consider the ability of the business to repay it. If you expect to lose money for the first year, you obviously won’t be able to repay a one-year loan on time. You’d be better off with intermediate or long-term financing. Finally, you need to consider amortizationSchedule by which you’ll reduce the balance of your debt.—the schedule by which you’ll reduce the balance of your debt. Will you be making periodic payments on both principal and interest over the life of the loan (for example, monthly or quarterly), or will the entire amount (including interest) be due at the end of the loan period?

A bank won’t lend you money unless it thinks that your business can generate sufficient funds to pay it back. Often, however, the bank takes an added precaution by asking you for securityCollateral pledged to secure repayment of a loan.—business or personal assets, called collateralSpecific business or personal assets that a bank accepts as security for a loan., that you pledge in order to guarantee repayment. You may have to secure the loan with company assets, such as inventory or accounts receivable, or even with personal assets. (Likewise, if you’re an individual getting a car loan, the bank will accept the automobile as security.) In any case, the principle is pretty simple: if you don’t pay the loan when it’s due, the bank can take possession of the collateral, sell it, and keep the proceeds to cover the loan. If you don’t have to put up collateral, you’re getting an unsecured loanLoan given by a bank that doesn’t require the borrower to put up collateral., but because of the inherent risk entailed by new business ventures, banks don’t often make such loans.

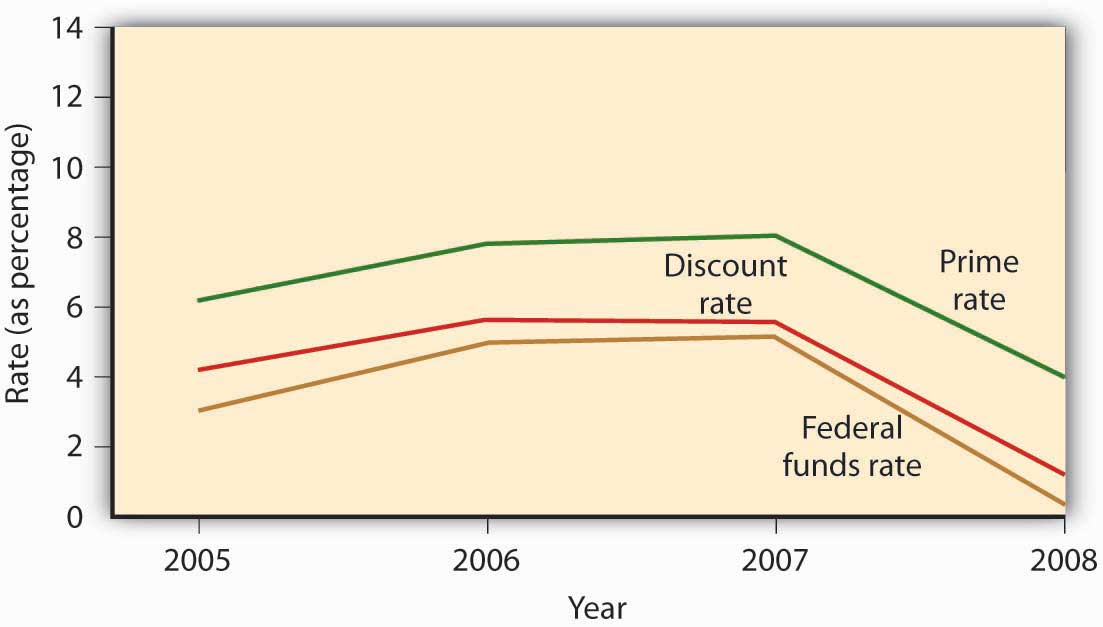

InterestCost charged to use someone else’s money. is the cost of using someone else’s money. The rate of interest charged on a loan varies with several factors—the general level of interest rates, the size of the loan, the quality of the collateral, and the debt-paying ability of the borrower. For smaller, riskier loans, it can be as much as 6 to 8 percentage points above the prime rate—the rate that banks charge their most creditworthy borrowers. It’s currently around 5 percent per year.

Now that we’ve surveyed your options, let’s go back to the task of financing your laundry business. You’d like to put up a substantial amount of the money you need, but you can only come up with a measly $1,000 (which you had to borrow on your credit card). You were, however, able to convince your parents to lend you $10,000, which you’ve promised to pay back, with interest, in three years. (They were wavering until you pointed out that Fred DeLuca started SUBWAY as a way of supporting himself through college).

So you still need $22,000 ($33,000 minus the $11,000 from you and your parents). You talked with someone at the Small Business Development Center located on campus, but you’re not optimistic about getting them to guarantee a loan. Instead, you put together a sound business plan, including projected financial statements, and set off to your local banker. To your surprise, she agreed to a five-year loan at a reasonable interest rate. Unfortunately, she wanted the entire loan secured. Because you’re using some of the loan money to buy washers and dryers (for $15,000) and a truck (for $6,000), you can put up these as collateral. You have no accounts receivable or inventories, so you agreed to put up some personal assets—namely, the shares of Microsoft stock that you got as a high-school graduation present (now worth about $5,000).

Flash-forward two and a half years: much to your delight, your laundry business took off. You had your projected five hundred customers within six months, and over the next few years, you expanded to four other colleges in the geographical area. Now you’re serving five colleges and some three thousand customers a week. Your management team has expanded, but you’re still in charge of the company’s finances. In the next sections, we’ll review the tasks involved in managing the finances of a high-growth business.

Cash-flow managementProcess of monitoring cash inflows and outflows to ensure that the company has the right amount of funds on hand. means monitoring cash inflows and outflows to ensure that your company has sufficient—but not excessive—cash on hand to meet its obligations. When projected cash flows indicate a future shortage, you go to the bank for additional funds. When projections show that there’s going to be idle cash, you take action to invest it and earn a return for your company.

Because you bill your customers every week, you generate sizable accounts receivable—records of cash that you’ll receive from customers to whom you’ve sold your service. You make substantial efforts to collect receivables on a timely basis and to keeping nonpayment to a minimum.

Accounts payable are records of cash that you owe to the suppliers of products that you use. You generate them when you buy supplies with trade creditCredit given to a company by its suppliers.—credit given you by your suppliers. You’re careful to pay your bills on time, but not ahead of time (because it’s in your best interest to hold on to your cash as long as possible).

A budgetA document that itemizes the sources of income and expenditures for a future period (often a year). is a preliminary financial plan for a given time period, generally a year. At the end of the stated period, you compare actual and projected results and then you investigate any significant discrepancies. You prepare several types of budgets: projected financial statements, a cash budgetFinancial plan that projects cash inflows and outflows over a period of time. that projects cash flows, and a capital budgetBudget that shows anticipated expenditures for major equipment. that shows anticipated expenditures for major equipment.

So far, you’ve been able to finance your company’s growth through internally generated funds—profits retained in the business—along with a few bank loans. Your success, especially your expansion to other campuses, has confirmed your original belief that you’ve come up with a great business concept. You’re anxious to expand further, but to do that, you’ll need a substantial infusion of new cash. You’ve poured most of your profits back into the company, and your parents can’t lend you any more money. After giving the problem some thought, you realize that you have three options:

Eventually, you decide on the third option. First, however, you must decide what type of private investor you want—an “angel” or a venture capitalist. AngelsWealthy individual willing to invest in start-up ventures. are usually wealthy individuals willing to invest in start-up ventures they believe will succeed. They bet that a business will ultimately be very profitable and that they can sell their interest at a large profit. Venture capitalistsIndividual who pools funds from private and institutional sources and invests them in businesses with strong growth potential. pool funds from private and institutional sources (such as pension funds and insurance companies) and invest them in existing businesses with strong growth potential. They’re typically willing to invest larger sums but often want to cash out more quickly than angels.

There are drawbacks. Both types of private investors provide business expertise, as well as financing, and, in effect, both become partners in the enterprises that they finance. They accept only the most promising opportunities, and if they do decide to invest in your business, they’ll want something in return for their money—namely, a say in how you manage it.

When you approach private investors, you can be sure that your business plan will get a thorough going-over. Under your current business model, setting up a new laundry on another campus requires about $50,000. But you’re a little more ambitious, intending to increase the number of colleges that you serve from five to twenty-five. So you’ll need a cash inflow of $1 million. On weighing your alternatives and considering the size of the loan you need, you decide to approach a venture capitalist. Fortunately, because you prepared an excellent business plan and made a great presentation, your application was accepted. Your expansion begins.

Fast-forward another five years. You’ve worked hard (and been lucky), and even finished your degree in finance. Moreover, your company has done amazingly well, with operations at more than five hundred colleges in the Northeast. You’ve financed continued strong growth with a combination of venture-capital funds and internally generated funds (that is, reinvested earnings).

Up to this point, you’ve operated as a private corporation with limited stock ownership (you and your parents are the sole shareholders). But because you expect your business to prosper even more and grow even bigger, you’re thinking about the possibility of selling stock to the public for the first time. The advantages are attractive: not only would you get a huge influx of cash, but because it would come from the sale of stock rather than from borrowing, it would also be interest free and you wouldn’t have to repay it. Again there are some drawbacks. For one thing, going public is quite costly—often exceeding $300,000—and time-consuming. Second, from this point on, your financial results would be public information. Finally, you’d be responsible to shareholders who will want to see the kind of short-term performance results that boosts stock prices.

After weighing the pros and cons, you decide to go ahead. The first step in the process of becoming a public corporation is called an initial public offering (IPO)Process of taking a privately held company public by selling stock to the public for the first time., and you’ll need the help of an investment banking firmFinancial institution that specializes in issuing securities.—a financial institution (such as Goldman Sachs or Morgan Stanley) that specializes in issuing securities. Your investment banker advises you that now’s a good time to go public and determines the best price at which to sell your stock. Then, you’ll need the approval of the SEC, the government agency that regulates securities markets.

(AACSB) Analysis

The most important number in most financial plans is projected revenue. Why? For one thing, without a realistic estimate of your revenue, you can’t accurately calculate your costs. Say, for example, that you just bought a condominium in Hawaii, which you plan to rent out to vacationers. Because you live in snowy New England, however, you plan to use it yourself from December 15 to January 15. You’ve also promised your sister that she can have it for the month of July. Now, in Hawaii, condo rents peak during the winter and summer seasons—December 15 to April 15, and June 15 to August 31. They also vary from island to island, according to age and quality, number of rooms, and location (on the beach or away from it). The good news is that your relatively new two-bedroom condo is on a glistening beach in Maui. The bad news is that no one is fortunate enough to keep a condo rented for the entire time that it’s available. What information would you need to estimate your rental revenues for the year?

(AACSB) Analysis

You’re developing a financial plan for a retail business that you want to launch this summer. You’ve determined that you need $500,000, including $50,000 for a truck, $80,000 for furniture and equipment, and $100,000 for inventory. You’ll use the rest to cover start-up and operating costs during your first six months of operation. After considering the possible sources of funds available to you, create a table that shows how you’ll obtain the $500,000 you need. It should include all the following items:

The total of your sources must equal $500,000. Finally, write a brief report explaining the factors that you considered in arriving at your combination of sources.

(AACSB) Communication

For the past three years, you’ve operated a company that manufactures and sells customized surfboards. Sales are great, your employees work hard, and your customers are happy. In lots of ways, things couldn’t be better. There is, however, one stubborn cloud hanging over this otherwise sunny picture: you’re constantly short of cash. You’ve ruled out going to the bank because you’d probably be turned down, and you’re not big enough to go public. Perhaps the solution is private investors. To see whether this option makes sense, research the pros and cons of getting funding from an angel or a venture capitalist. Write a brief report explaining why you have, or haven’t, decided to seek private funding.