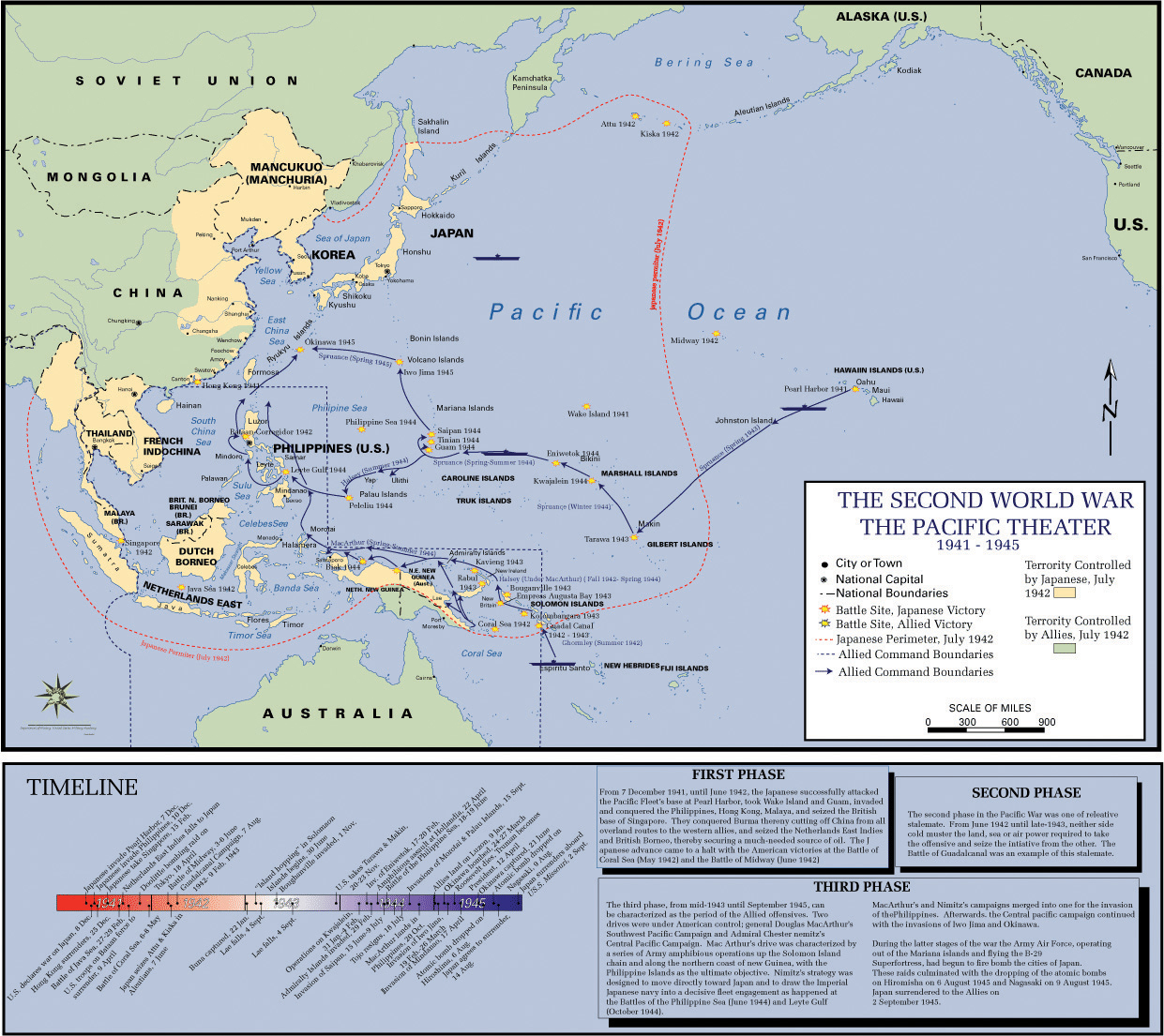

In response to Japanese aggression throughout Asia, the United States placed a trade embargo on the Japanese Empire. President Roosevelt hoped that halting Japan’s access to oil would cripple Japan’s military and halt its aggression in Asia. Instead, it led to a surprise attack by the Japanese against the US naval base at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii on December 7, 1941. America responded with a declaration of war against both Japan and Germany. The declaration revealed that the nation was not yet prepared for a global war. As had been the case in World War I, American leaders quickly sought to mobilize all of the nation’s resources in support of the war effort. For the next four years, American industry concentrated on maximizing production of war materiel while 11 million women and men joined the armed forces.

The American way of war was based on developing an overwhelming force that could defeat an enemy with the minimum loss of life among its own troops. This required a superior amount of weaponry and support material and was also based on training and logistics. As a result, the United States was slow to mobilize and its allies in Europe and Asia were left to fight much of the war on their own until American troops arrived. Once those soldiers arrived, however, the tide of war shifted decisively toward the Western Allies.

The war would have an equally dramatic impact on the American home front. Japanese Americans were forced into internment camps until it was shown that such prejudices did nothing to advance the security of the American homeland. Other forms of discrimination were equally slow in being surmounted, with prohibitions against the service of women and minorities being only partially removed in the face of military necessity. As America raced to maximize its human resources to increase industrial production, it also decided that the price of prejudice was too high and began to celebrate its increasingly diverse workforce.

Ideas about limited government were also tested by the crucible of war. In response to the need to coordinate production and maximize efficiency, the federal government expanded its authority over the private sector. Although some feared that central planning might lead the nation to become more like the socialist and fascist nations of Europe, the American way of preparing for war was also unique. Although the government maintained the coercive power to seize factories it rarely did so, offering instead the possibility of high profits and high wages for those who produced the equipment and weapons it needed. By 1945, the US home front produced approximately half of the world’s weaponry and the empires of Germany and Japan surrendered.

Few Americans were willing to consider military action against the Japanese in 1940 and 1941, and most considered Asian affairs to be of secondary importance to the events in Europe. To the Japanese, however, the United States embargo was an act of aggression that would make its empire vulnerable at the very moment it was expanding throughout Asia. From this perspective, there appeared little reason to maintain diplomatic relations with the United States. The Japanese now viewed the US-controlled Philippines much in the same context as the Dutch, French, and British colonies in Southeastern Asia. Hitler’s war on these European powers could not have occurred at a better time for Japanese imperialists. They convinced the Japanese emperor that their alliance with Germany provided an opportunity for Japanese expansion into Southeastern Asia. With these European nations fighting for their very survival, Japan attacked their colonies throughout the region and seized control of raw materials and trade routes. Before these attacks were launched, however, Japanese officials launched a surprise attack on the United States they believed was necessary to prevent US interference.

With China and the Europe fighting for survival, Japan expected little resistance in Southeastern Asia. In fact, the Japanese recognized that only one major naval power stood in their way of conquest—the United States. Japanese planners recognized that further aggression in Asia might lead to a more aggressive response than a trade embargo. (Historians now know that US military and civilian leaders had already determined not to intervene with military in Asia, even if Japan attacked US bases in the Philippines.) The Japanese fully recognized the industrial power of the United States; however, they believed a sudden and devastating attack on America’s Pacific Fleet at Pearl HarborA surprise attack launched by the Japanese navy on the American Pacific Fleet anchored at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii on December 7, 1941. The attack resulted in the deaths of over 2,000 US servicemen and servicewomen and greatly reduced the effectiveness of the fleet. However, the attack failed to destroy US aircraft carriers and resulted in the US declaration of war against Japan, Germany, and Italy. would cripple the US navy for at least a year. During the interim, Japan planned to complete its conquest of Southeast Asia and build impenetrable defenses throughout the region. America’s first opportunity to launch a counterattack would not occur until the summer of 1943, and by this time, the Americans would be ill-advised to send their newly rebuilt navy into the Japanese stronghold for its second slaughter.

By the winter of 1941, US leaders determined that they would no longer trade with Japan unless they ended their expansionistic campaign. In November, the United States demanded that Japan withdraw from China before any resumption of trade could commence. The talks quickly stalled on this point since the leading reason the Japanese sought oil from the Americans was to facilitate the expansion of their empire. By this time, Japanese forces had been secretly preparing for an attack against Pearl Harbor for over a year. In fact, US intelligence officers intercepted messages warning of the possibility of an attack should trade negotiations fail. Given the proximity of the US-controlled Philippines to Japan, many predicted that any attack would occur on these islands. While the military leaders debated on how to respond to a potential attack on the Philippines, all Pacific bases were ordered to increase their internal security. While officials at Pearl Harbor were on alert for potential acts of sabotage, few even considered the possibility of a carrier-based attack 4,000 miles from the Japanese mainland.

Just before 8:00 a.m. on Sunday, December 7, 350 Japanese warplanes launched in two waves from six aircraft carriers attacked America’s Pacific Fleet anchored at Pearl Harbor. Each of the eight battleships that were present that morning was damaged, while half of them were destroyed. The attack also sunk a dozen other warships and destroyed nearly 200 aircraft. Of the 2,402 US servicemen who perished that day, nearly half were aboard the USS Arizona when a bomb caused its forward ammunition magazines to explode. The Japanese lost only a handful of aircraft in the attack. Their commanders recognized that despite the apparent success of their mission, it had failed to achieve its primary objective of crippling the US Pacific fleet. Although US losses were high, all three of the fleet’s aircraft carriers escaped destruction at Pearl Harbor because they had been out to sea for various reasons.

Figure 8.1

The USS West Virginia burns in the background while a crew saves a navy seaman who was able to escape the destruction.

Hours after the attack at Pearl Harbor began, Japanese warplanes began an assault on US forces stationed in the Philippines. For reasons that are still unclear, General Douglas MacArthur failed to mobilize in preparation for this attack, and Japanese aircraft destroyed most of United States’ Far East Air Force, which was still on the ground. Roosevelt addressed Congress on December 8. The president declared the attack at Pearl Harbor to be a “date which will live in infamy” and requested a declaration of war. Congress agreed, and the United States officially declared that a state of war existed with Japan, as well as Germany and Italy.

The American people overwhelmingly supported their president’s request for war following the attack on Pearl Harbor. Even former isolationists agreed; they could be found among those who joined the military or otherwise helped their nation prepare for the impending struggle. Indignation at the attack soon turned to fear as Japan defeated French, British, and Dutch colonial forces throughout Southeastern Asia. America’s own position in the Pacific was equally perilous. US bases on Guam and Wake Island surrendered to the Japanese. By early 1942, many predicted that a second attack on Pearl Harbor would lead to the capture of Hawaii. Americans on the West Coast feared that a Japanese-controlled Hawaii would be used to stage an invasion of the US mainland.

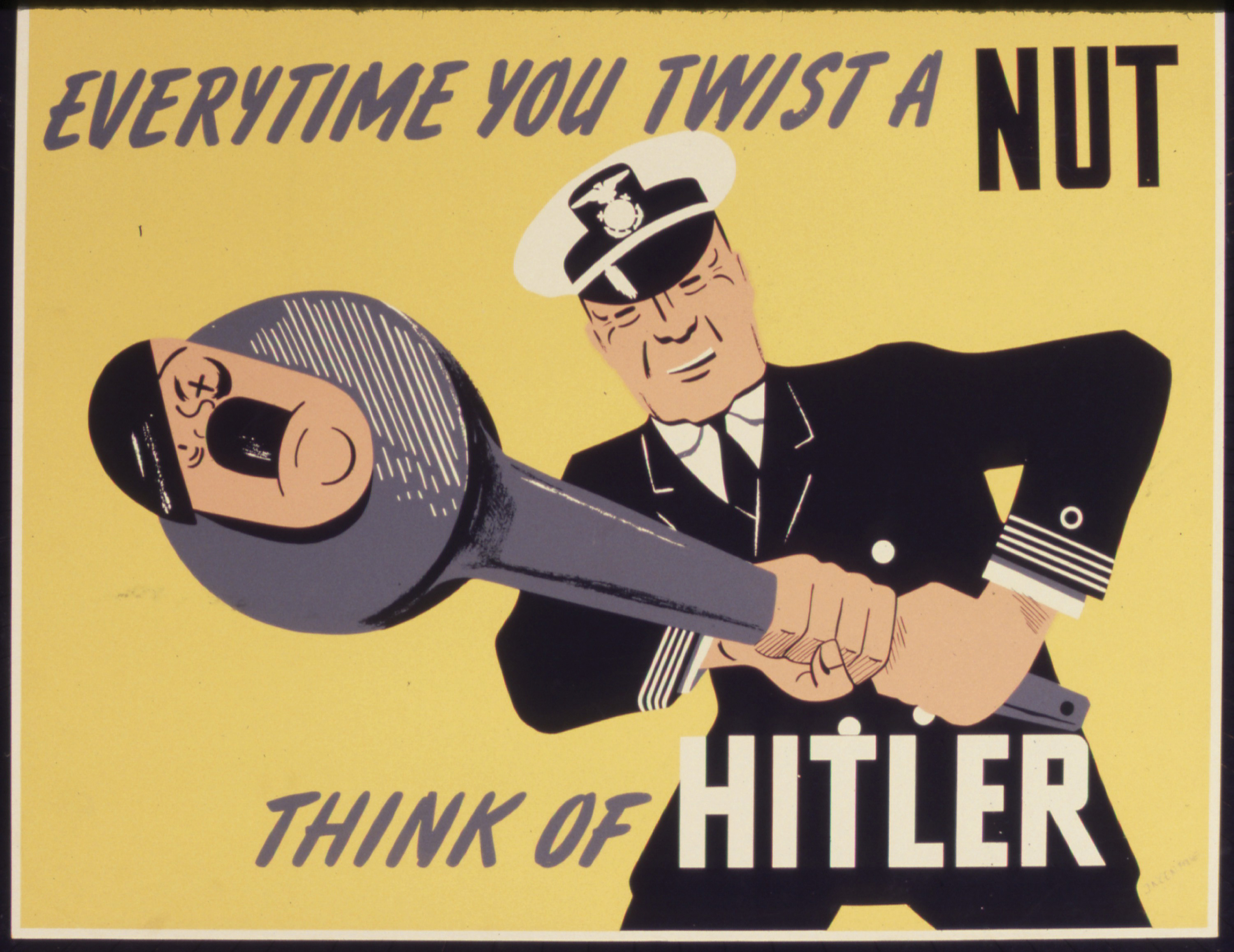

Figure 8.2

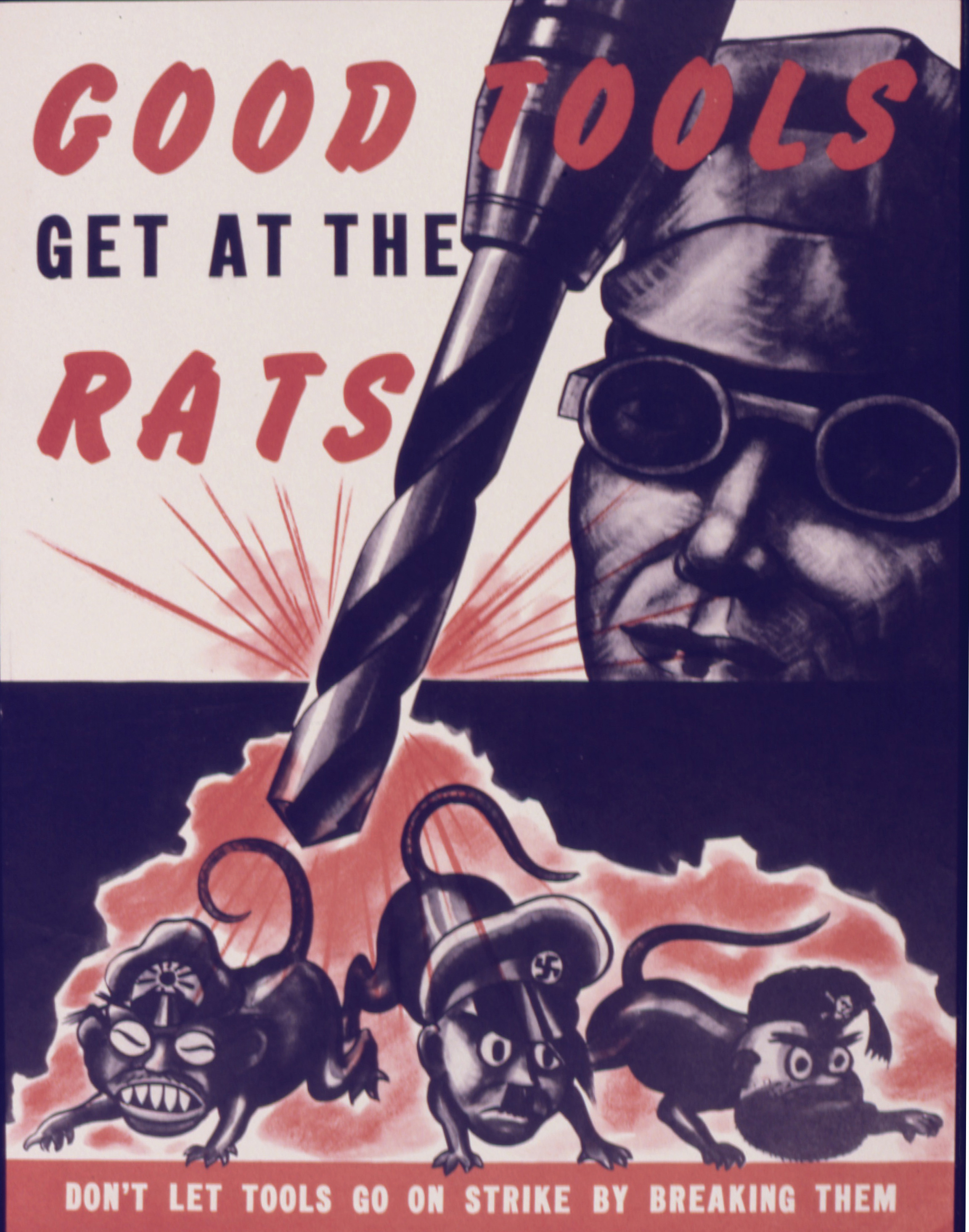

The War Production Board made a number of posters meant to motivate workers in the defense industry by connecting their labor to the war effort. Many of the images depicted laborers directly hurting Hitler or the emperor of Japan by building weapons and equipment.

Following his declaration of war in December 1941, Roosevelt sought ways to convert the United States into “the arsenal of democracy” that supplied America and its European allies with the weapons needed to defeat Hitler’s armies. This vision embodied both the idealism and economic might of the nation. It also demonstrated his belief that the United States was unique in its capacity for both representative government and industrial production. However, America was still mired in the Depression in 1939. Perhaps worse, a vast gulf existed between the desire of Americans to take the war to Japan and Germany and the present state of their army and navy. Roosevelt and Congress responded to the emergency by enlarging the military and expanding the government’s role in the economy in ways never before imagined, even at the height of the New Deal. In the next few years, the United States became the arsenal Roosevelt described. Section 8.3 "D-Day to Victory" examines the expansion of the military and the transition to a wartime economy. Whether this arsenal was truly democratic largely depends on the perspective one considers. Section 8.4 "Conclusion" follows with a review of this question from the perspective of women and minorities.

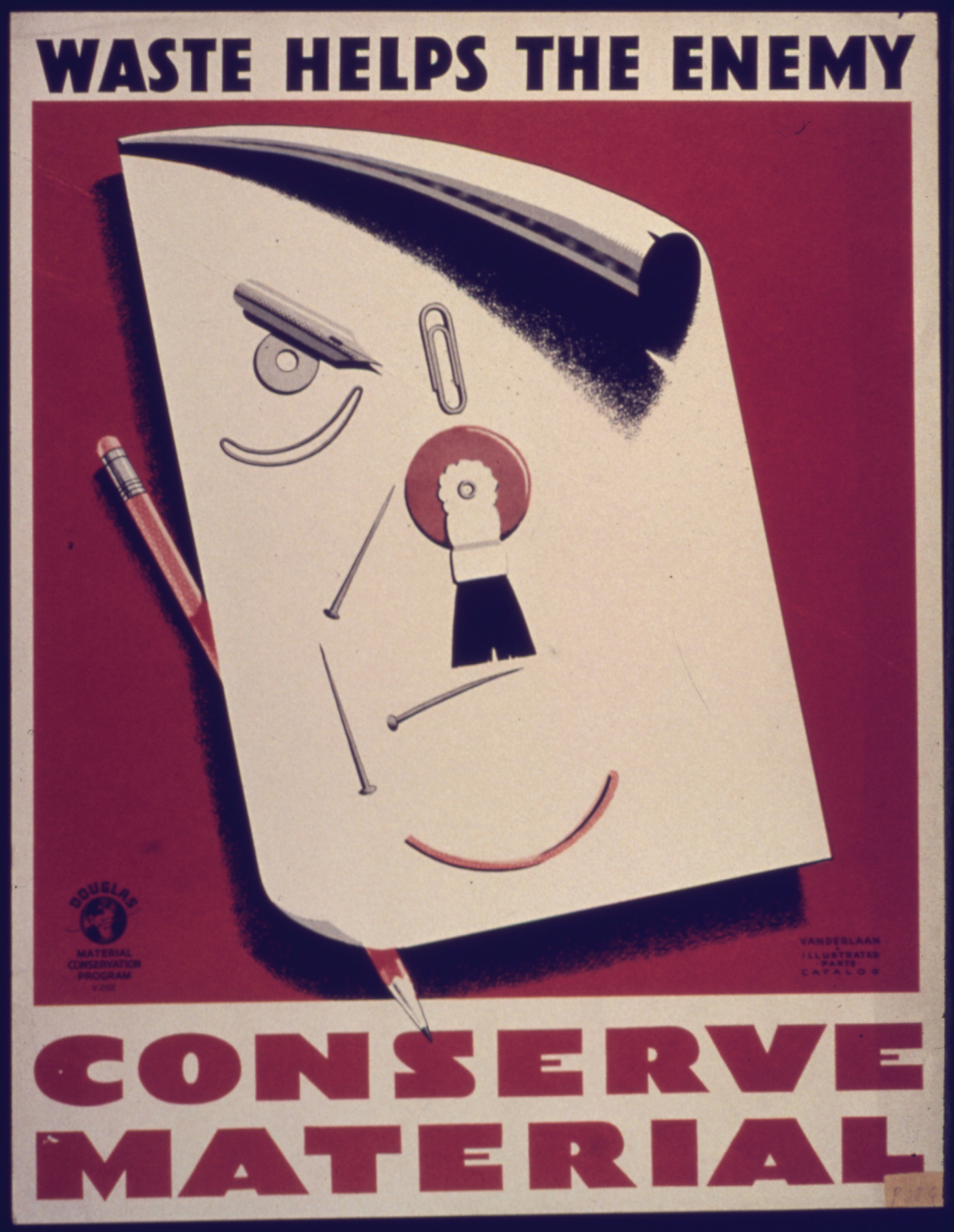

Figure 8.3

Many of the posters made by the federal government were humorous, such as this poster imploring Americans to make efficient use of everyday products to conserve materials that might instead be used to produce supplies for the military.

Even in the Depression year of 1937, America produced ten times as many automobiles as Germany and Japan combined produced. However, two decades of isolationism kept US military spending low, and few US companies produced combat aircraft, tanks, or other munitions so desperately needed by the United States and its allies. If US factories could quickly transition from producing consumer goods such as automobiles to tanks, ships, aircraft, and trucks for its armed forces, the Allies would quickly enjoy an abundance of military equipment. The revision of the Neutrality Act in 1937 and the abandonment of its restrictions on wartime trade between 1939 and 1941 had already led to increased military production by US companies. In addition, Congress appropriated nearly $2 billion in defense spending in 1940 and another $6 billion the following year. Still, ensuring that most US companies shifted from producing vacuum cleaners to machine guns required more than an increase in military purchase orders. Given the sudden transition back to civilian production after World War I, US companies were hesitant to invest the money needed to convert their factories from building refrigerators to machine guns. Any number of events could lead to the sudden cancellation of military purchase orders, they reasoned, and their companies would then be stuck producing goods that were no longer demanded.

The government also had to contend with the long-term effects of the Great Depression. In 1940, 8 million workers were still unemployed, and half of the nation’s manufacturing plants were producing below half of their maximum capacity. As a result, the federal government took even greater control of the economy than it had during World War I to make sure that its factories were at peak capacity. For example, the federal government ordered the end of civilian auto production in 1942 as a means of ensuring that more military vehicles were built. The government also created a New Deal–like alphabet soup of programs charged with overseeing the transition to full wartime production.

As the war raged in Europe, Roosevelt announced production goals few thought possible. The federal government worked to ensure US businesses met these goals by using a carrot-and-stick approach. Very lucrative contracts became the carrot as the federal budget increased tenfold during the war. These expenditures allowed government purchasing agents to offer lucrative deals to US business leaders, convincing nearly all leading industries to convert to wartime production. The government paid top dollar for all manner of goods from food to flamethrowers while occasionally seizing manufacturing facilities it felt were not being fully utilized.

The Roosevelt administration’s solution to underproductivity thus demonstrated a uniquely American approach that blended free enterprise with unprecedented government intervention. The War Production BoardA federal agency directed with procuring all military supplies and armaments and managing the conversion of factories from civilian production to military production. The board sought to achieve peak efficiency by offering lucrative contracts to businesses producing material considered vital to the war effort while restricting or banning the production of nonessential items. offered tax incentives, loans, and even guaranteed profits to businesses that were now understandably eager to produce the goods the military desired. Other government agencies seized control of commodities markets to make sure that these businesses would have access to the raw materials they needed. The Office of Price AdministrationA federal agency tasked with limiting inflation and profiteering during the war by imposing price limits on scarce items such as oil and tires. The agency also froze prices on food items and rent to prevent speculators from buying up large quantities of vital resources and selling them for much higher prices in a time of national emergency. regulated the cost of these raw materials, as well as the prices of consumer goods, to reduce inflation and prevent price gouging of ordinary consumers.

As a result, corporate profits more than doubled between 1941 and 1945. US business leaders could have never dreamed of such a favorable contract, with nearly every expense related to building or converting existing factories being tax deductible. Other contracts offered guaranteed profits on each item produced for the military. Workers benefited as unemployment became a problem of the past, while wages jumped by 30 percent. Because virtually all segments of the population stood to profit from the government’s economic programs, criticism was limited to those who opposed the principle of government-imposed economic planning and management. Economist Friedrich HayekAustrian economist who argued that central planning could never be as efficient as the free market. The Road to Serfdom argued that complete governmental control of the economy, including central planning over decisions regarding production, distribution, and consumption that typified a Socialist state, would lead to increased governmental control of all aspects of life and eventually lead to totalitarianism. Hayek believed that a free market system with limited governmental regulation of certain functions such as banking provided the best economic results while safeguarding the freedom of the individual. authored The Road to Serfdom in 1944, arguing that complete control of the economy by government was a trademark of dictatorship.

Influenced by Hayek, many Americans were uncomfortable with the sudden expansion of their government’s authority. The War Production Board utilized economic planning that seemed to share similarities with the totalitarian governments of Japan, Germany, and the Soviet Union. At the same time, Americans could point to important differences. Private enterprise still prevailed in nearly every sector of the economy. The federal government rarely used its coercive power to seize a plant or halt a strike, and Americans enjoyed average incomes that were larger than those of German, Italian, and Japanese workers combined. Perhaps most important, the federal government’s plan succeeded in increasing military production without creating major hardships on the home front. Even if certain items like nylons were no longer available to civilians, America’s total output of consumer goods actually increased during every year of the war. If America’s economy could no longer be categorized as free enterprise, it seemed to many that it could not be considered Socialistic either.

Critics who bemoaned the rise of government interference in the economy could offer little rebuttal against the overwhelming statistics of America’s wartime production. As early as 1942, the United States was producing more military equipment than any other nation. By 1945, US factories were responsible for nearly half of the world’s armaments and had out-produced the factories and farms of England, France, Russia, Germany, Italy, and Japan combined. In total, America produced more than 300,000 aircraft, 100,000 tanks and armored vehicles, 22 aircraft carriers, 8,000 transport ships, and 1,000 armed vessels for the navy. Armament plants churned out 40 billion bullets that could be fired by the 20 million rifles that were made. US factories produced a new all-purpose military vehicle known as the jeep every minute, while a new plane took off from runways adjacent to US factories every five minutes. Massive cargo ships that used to take one or two years to complete were now produced in a matter of weeks. Dubbed “liberty ships,” these cargo vessels were indispensable to the American way of war that relied upon overwhelming material supremacy.

US factories were not only more productive than their rivals, but they were also more innovative. Funding for research and development led to the effective military application of technologies such as radar, sonar, proximity fuses, computers, and jet aircraft. The most important new military technology was the realization of an atomic bomb that had only been theorized about by a small number of physicists in the past. The federal government spent more than $300 billion to achieve this mix of production and innovation—more than double the entire federal budget for the last 150 years of the nation’s existence. The result was an undeniable superiority of equipment that would allow US troops to quickly win the war while suffering only a fraction of the casualties of their Russian and Chinese allies. Ill-trained and poorly equipped, tens of thousands of Russian and Chinese soldiers perished each week while awaiting the arrival of US forces.

In retrospect, it is clear that Hitler’s decision to invade Russia bought the United States time to make this amazing economic transition. Russia did not fold as many had predicted, but instead kept the German army occupied for the duration of the war. Few understood the disastrous potential of a stalled Russian offensive more than Hitler did. The Fuhrer’s advisers cautioned Hitler that he would have but one year to defeat Russia. After this time, the combination of US industrial production and Russian manpower might negate the initial momentum and superiority of equipment the Germans enjoyed. Japanese Admiral Isoroku YamamotoJapanese Naval commander who doubted the wisdom of attacking the United States. Sensing that others did not share his concerns, he created a strategy based on seeking a decisive victory over the American Pacific fleet that he hoped would at least temporarily paralyze the US Navy. Understanding that the attack at Pearl Harbor had failed to meet this objective, he hoped to trap and sink the remaining US aircraft carriers in the Battle of Midway. made a similar prediction regarding his nation’s war against the United States. Yamamoto argued that a successful attack against Pearl Harbor would buy the Japanese navy a year of unchallenged supremacy in the Pacific. If the war continued for a second and third year, he warned, America’s industrial would negate its inertia and put the Japanese empire on the defensive. As a result, both Japan and Germany based their 1941 decisions to attack the United States and Russia on their belief that the war would end quickly. Every day that the Russians and Chinese held out against German and Japanese forces provided US factories and military planners with more time to prepare.

America’s military production and preparation was facilitated by massive government spending. Given the dire necessity of building a military and the benefits to workers and industry alike, few criticized the government’s use of borrowed money to finance the war effort. The greatest concern at the time was not the government’s ability to repay this money, but whether the sudden influx of federal spending would lead to inflation. The methods of financing the war, however, absorbed most of the extra money that was moving into the economy.

The Revenue Act of 1942Lowered the minimum income requirement for which wage earners must pay federal tax. Accepted by many as a necessary method to finance the war, the law forever changed the nature of taxation in the United States. doubled the amount of money the government received from individual tax returns and forever changed the nature of income tax in America. The law reduced to $1,200 the amount of money that was exempt from federal taxation for families. Since the average income of an American family was just over $1,200, most full-time wage-earners had not paid any federal tax prior to 1942. The following year, the government mandated that employers withhold taxes from each worker’s paycheck. By taking out small amounts from each check rather than presenting families with a large bill at year-end, this provision helped to ensure that federal taxes were collected. The number of Americans required to file and pay federal taxes jumped from 4 million to 45 million by the end of the war.

Roosevelt and Congress fought a fierce battle regarding these changes to the tax code, with the increasingly conservative House of Representatives and Senate rejecting many of the president’s requests for even steeper tax increases. Roosevelt favored taxation because he feared the consequences of too much borrowing. However, tax increases were a bitter pill for members of the House of Representatives who faced two-year election cycles. Because of these political considerations, the government followed the tradition of financing wars through heavy borrowing. Corporate and personal income taxes financed 45 percent of the war’s cost. The government made up the difference by borrowing nearly $200 billion, 20 percent of which was held by private citizens who had purchased war bonds.

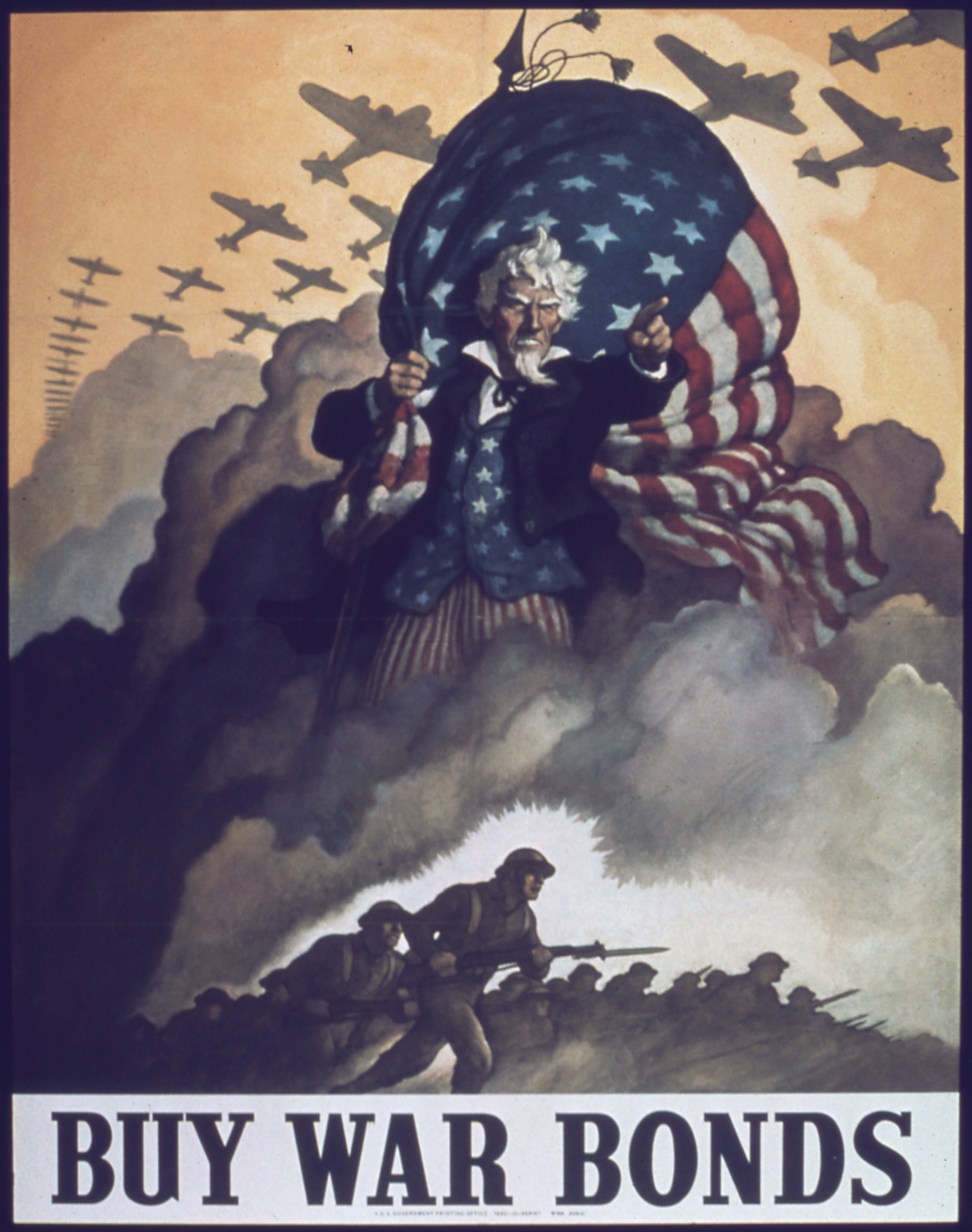

Figure 8.4

Posters produced by the Office of War Information (OWI) urged Americans to purchase war bonds by connecting their investments to the war effort.

As had been the case in previous conflicts, these sales once again served the purpose of mobilizing Americans behind the war effort. Similar to the efforts of George Creel and others during World War I, the government recruited celebrities and athletes to headline bond drives. Purchasing a government bond was more than just a patriotic gesture; bonds represented a secure investment that provided guaranteed repayment with interest. The revenue from these bonds would help many families purchase more goods once the war was over and ensured that civilian production of items such as automobiles and new homes would resume. At the same time, repayment of these bonds decreased the likelihood that federal income tax rates would return to their prewar levels once the war was over.

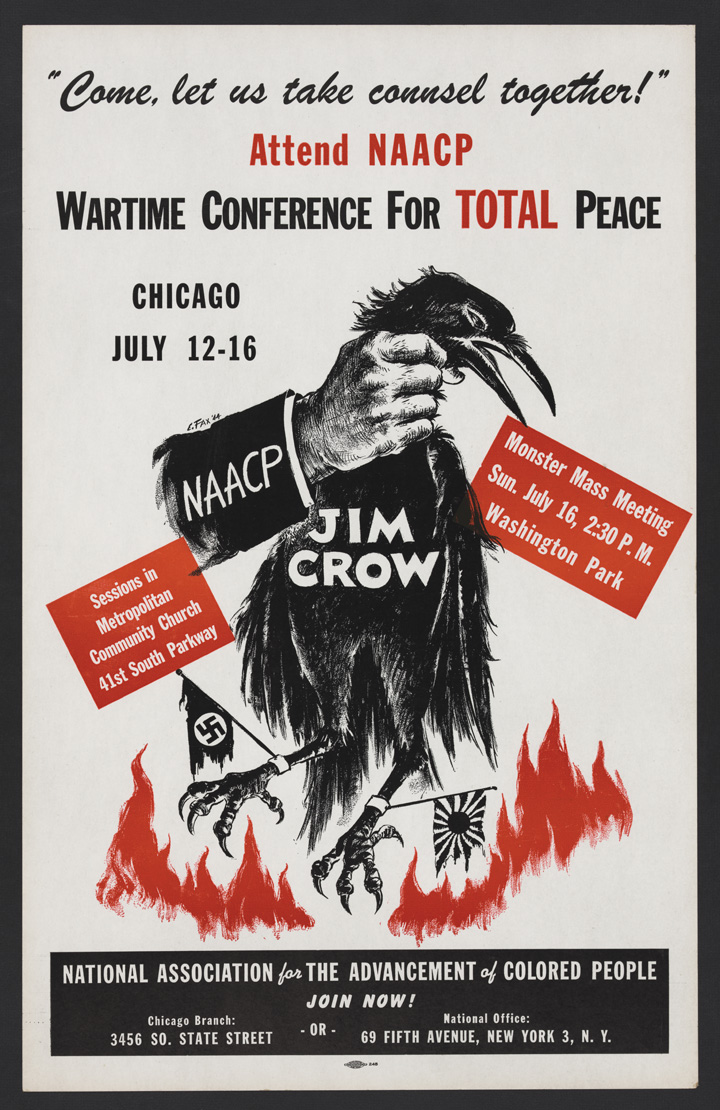

Contrary to World War I, few Americans questioned the necessity of America’s involvement in the Second World War. The government’s Office of Censorship was limited to monitoring soldiers’ letters and preventing the release of sensitive information that might be of value to the nation’s enemies. The Office of War Information (OWI)A government agency tasked with improving morale and managing the public image of the war effort. The attack against Pearl Harbor resulted in few Americans opposing the war itself, freeing the Office of War Information to mobilize public opinion in support of various government initiatives rather than engaging in censorship. The OWI made films, radio broadcasts, pamphlets, and other forms of wartime advertisements, but it is most remembered for its colorful and creative posters. A division of the OWI created pamphlets and other materials distributed overseas designed to reduce the morale of enemy troops and civilians. was tasked with mobilizing the already favorable public opinion of the war effort into support for various government initiatives. The transition from censorship in World War I to a more tolerant view of dissent is demonstrated by a 1943 Supreme Court ruling that tolerated those who refused to salute the flag for religious or personal beliefs. The decision illustrated a departure from the state-mandated displays of nationalistic support in Germany and Japan, a theme that was often featured in OWI releases lauding America’s toleration for dissent in contrast to the totalitarianism of her enemies. In general, OWI propaganda sought to portray the war as a moral struggle between freedom and totalitarianism. Most OWI posters and films were upbeat, praising America’s industrial workers and soldiers and encouraging them to continue their efforts, rather than demonizing the enemy. Yet when it came to the war in the Pacific, OWI propaganda pandered to existing prejudices against the Japanese. Posters and films alternated between portraying the Japanese as diminutive monkeys or rats and hulking ape-like beasts. The imagery was increasingly violent, such as a poster advertising war bonds that depicted a caricatured Japanese head being decapitated from a rat’s body. Critics pointed out that anti-German posters were restricted to demonic images of Nazi leaders, while the war against Japan was increasingly presented as a war against a subhuman race.

The OWI employed a few thousand writers and artists who tended to favor not only the war effort but also the ideas of New Deal liberals. Most OWI publications promoted noncontroversial subjects such as general support for the troops, conservation of materials, and a partnership between industrial workers and the troops on the front line. Some OWI publications also sought to promote more liberal ideas, such as the notion that fair pay, medical care, and full employment were rights for which Americans were fighting. As a result, the OWI budget was vastly reduced by an increasingly conservative Congress.

The government granted wider latitude to conscientious objectors and dissenters than in previous wars, largely because so few Americans doubted the basic premise of their nation’s participation in the war. Contrary to World War I, America had been attacked and faced a clear moral decision to intervene in both Asia and Europe against the rise of totalitarian regimes. Even reducing the funding for the OWI did little to reduce prowar propaganda as private entities also sought to promote the war. Newspapers were full of daily editorials on the need to fight the Germans and Japanese, and Hollywood produced a litany of films eulogizing the valor of soldiers. While most of this propaganda focused on support for soldiers and celebration of industry, some of this propaganda played to the anger of Americans after Pearl Harbor and even pandered to ethnic and racial hatred.

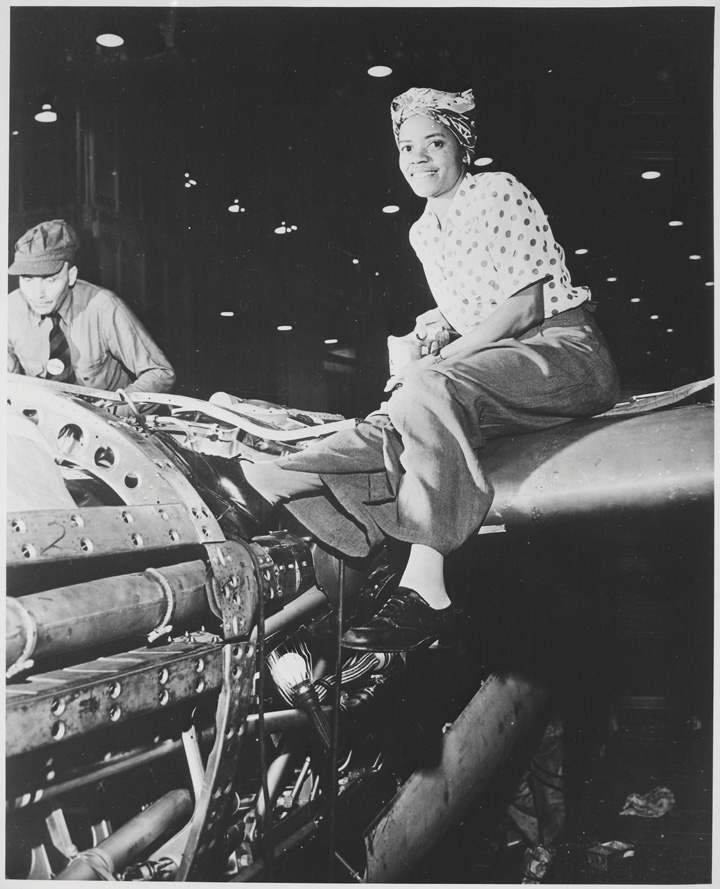

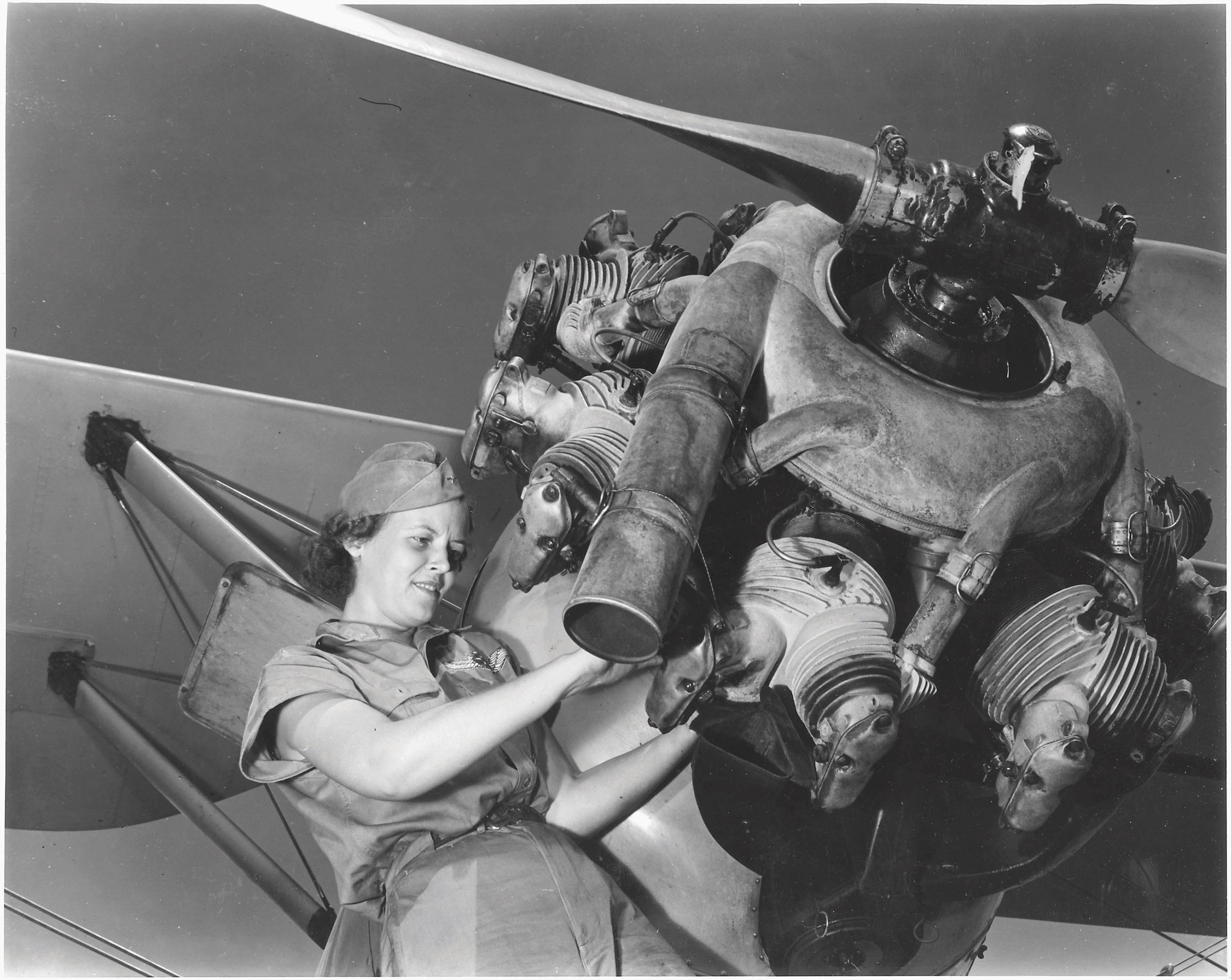

As America prepared to enter the war, Roosevelt indicated that the nation would not simply match the production of its enemies but instead would crush those enemies with overwhelming material superiority. At its peak, the nation rolled out a new tank and airplane every five minutes. This superiority of equipment kept US casualties low compared with Russia, China, and the Axis Powers. Such production could only be achieved by the addition of 15 million new workers entering US factories for the first time during the war years. Women represented half of these new employees and one-third of the total civilian work force. Many women continued to work in service, clerical, education, and nursing fields, but many of the 6 million women who joined the paid workforce for the first time took up manufacturing jobs traditionally held by men. For many women, entrance into the paid workforce was both ennobling and exhilarating, opening new opportunities and providing a measure of financial independence. Even if only 10 to 20 percent of working women were employed within the defense industries, the can-do image of Rosie the RiveterA mythical female steelworker who came to represent the millions of American women who entered jobs in factories during World War II. A cultural icon whose name derived from popular song lyrics, real life “Rosies” were women who worked jobs previously open only to men. both represented and inspired many women, whether they donned overalls and “manned” the assembly lines or worked more traditional jobs. Minority women seldom experienced the same opportunities for direct upward mobility, yet for many, the war provided the first time a US factory would consider hiring a woman of color for any position at any wage.

Figure 8.5

One of many real-life “Rosie the Riveters,” this woman built military aircraft at a Lockheed plant in Burbank, California.

Despite the entrance of approximately 2 million women into jobs traditionally held by men, wartime propaganda minimized the challenge this trend represented to traditional images of gender. Women’s work in defense factories was portrayed as falling within the larger role of women as guardians of the home and family. The war temporarily redefined the domestic sphere to include the home front as well as the household. Men were still in charge and the defenders of the nation, Americans were assured by the prevailing culture, as women entered factories only to assist the men who performed the more difficult and essential tasks. Female production of armaments that were used by men to defend the nation was viewed as compatible with prevailing labor arrangements where women assisted men. A woman on a bomber assembly line performed simple, mindless tasks in support of a skilled pilot flying over enemy territory, this line of reasoning suggested, just as a female secretary might perform routine tasks in support of her male boss, who skillfully navigated the cutthroat world of business. The internal contradictions of this reasoning were evident to many, yet the culture and limited duration of the war conspired to minimize wartime challenges to American notions of work and gender.

Despite the unprecedented number of women in the workforce, American men and women alike were reluctant to abandon traditional lines between male and female labor. The majority of women between the ages of eighteen and sixty-five did not enter the paid workforce at any time during the war. The majority of women who did indicated repeatedly in editorials and opinion polls that they agreed with prevailing notions insisting that female labor in factories was a temporary necessity due to the 16 million men and women who served in the armed forces between 1941 and 1945. These female laborers averaged only 65 percent of the wages paid to men for the same work. They were also usually expected to quit these jobs after the war, although some businesses reasoned that continuing to employ women might provide significant cost savings. Most of the women in these fields voluntarily left their jobs. However, societal expectations and the likelihood that most women would be fired from industrial jobs if they did not resign makes it difficult to determine how voluntarily American women retreated from the factory to the home.

Labor unions had benefitted from the enrollment of female workers, yet they were still dominated by men and supported the idea that returning veterans should replace their former sisters of toil. During the war years, however, the unions actively sought to adapt to the changes around them by forming partnerships with government and management. Labor leaders recognized the need to maximize wartime production as a national defense issue and as a means of benefiting their members. As a result, nearly every union leader pledged not to support labor strikes and resolved to work with the National War Labor Board (NWLB)A federal agency established in World War I and reestablished by President Roosevelt in World War II to arbitrate disagreements between labor and management. As was the case in World War I, the primary objective of the NWLB was to prevent work stoppages that might derail production of essential wartime supplies and munitions. to arbitrate disputes with employers.

In return for labor’s pledge to avoid strikes, the government agreed to regulate consumer prices to ensure that inflation did not dilute worker wages. The federal government even purchased food directly from farmers and sold it to retailers at a financial loss to keep consumer prices down. More importantly to labor leaders, the government also passed a “maintenance of membership” rule that required all new employees in factories represented by a union to join that union. This arrangement satisfied most labor leaders as their membership rolls expanded. Due to rising wages and the resulting power of the unions, most union members enjoyed significant pay increases and even new benefits, such as pensions and health insurance.

Figure 8.6

This poster urges workers to be careful with their equipment. It also presents the idea that any kind of work stoppage would harm the war effort—a clear attempt to also discourage labor strikes.

Workers in some industries felt that their pay increases failed to keep pace with corporate profits. Others cited mandatory overtime, assembly line speed-ups, and the occasional wage freezes in some industries as mandated by NWLB agreements. John L. Lewis, head of the United Mine Workers, believed that the NWLB cared little for the miners of his organization. Lewis argued that his miners were not enjoying their proportional share of wartime prosperity given the higher prices of coal, steel, and other mining commodities. Lewis ordered a strike that halted mining operations throughout the country and threatened to halt defense production. As a result, the miner’s strike sent panic through the nation and led many to equate labor activism with treason. Given the nation’s immense need for coal, iron ore, copper, and other metals, Lewis won significant concessions for his members. The fallout from this strike, however, caused the entire labor movement to lose public support. Congress also responded by passing several laws that limited the power of unions for the duration of the war.

Even before the United States joined the war, Congress approved the Selective Service Act of 1940 to address concerns that the army might not be able to defend itself if the war spread from Europe to North America. The law required young men between the ages of twenty-one and thirty-five to register for the draft. The law also classified registrants into four categories. Those who were deemed physically and mentally fit who were single and not employed in an occupation deemed “critical” by the War Department were placed into Category I. Those so placed could expect a draft notice and often chose to enlist rather than wait to be called by their Uncle Sam. Deferments for married men proved temporary, especially after the government noticed a sudden spike in weddings that seemed curiously related to the arrival of draft notices. Fatherhood was the next deferment to succumb to military necessity. However, during the first years of the war, so few dads were drafted that newborns were occasionally nicknamed “weatherstrips” because they insulated families by keeping their fathers out of the draft.

The nation had only 1.6 million soldiers and sailors at the time of the attack on Pearl Harbor, half of whom had enlisted after Roosevelt’s enactment of a peacetime draft in 1940. This number would increase nearly tenfold by the end of the war, with 150,000 recruits entering one of 250 training camps set up around the country each week. Most of these recruits had never been far from home but were now sharing bunks and foxholes with others of different ethnic and religious backgrounds. As a result, the war led many to broaden their horizons and shed their prejudices, while others simply became more distrustful of those who seemed different from themselves.

Figure 8.7

A 1942 recruiting poster for the US Army Air Corps. The United States Air Force did not become its own independent branch of the armed services until after World War II.

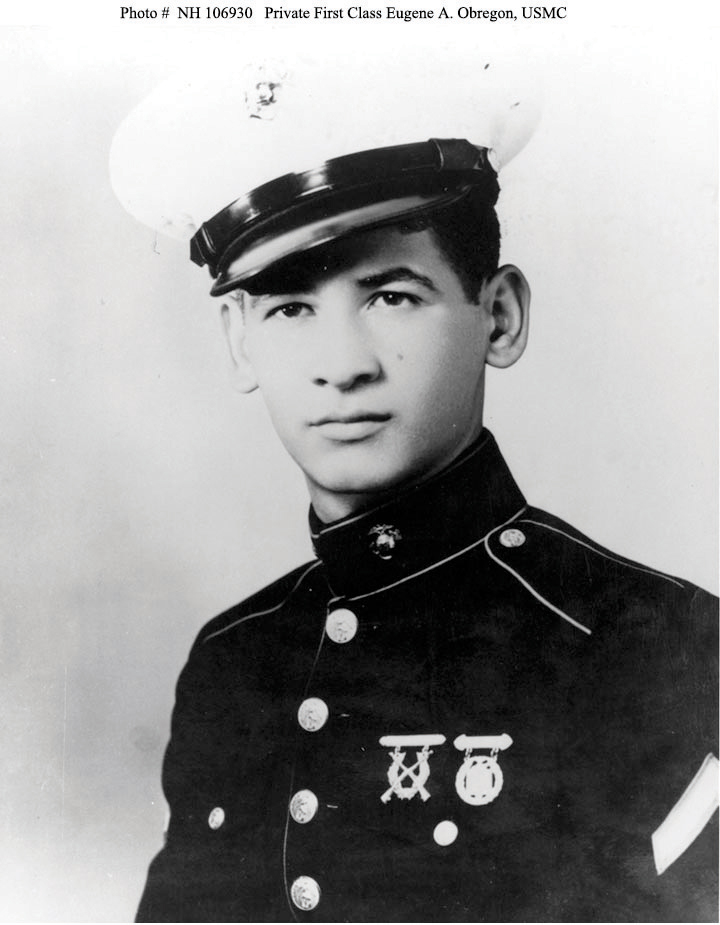

African American troops were the only soldiers explicitly required to endure segregation. However, many West Coast units were composed entirely of Mexican Americans, Japanese, or Filipinos. Puerto Rican recruits were often grouped together in places such as Florida and New York. Elsewhere, informal segregation usually prevailed as Jewish, Asian, Native American, and other groups usually banded together given shared experiences and the prejudices they encountered from others. A large percentage of military members were first- or second-generation immigrants, many of whom were not yet fluent in English. As a result, the war accelerated the assimilation of many soldiers and helped to break down prejudices against immigrants from other parts of the world. A similar breakdown of racial prejudice was prevented by the War Department’s decision to maintain separate units for black troops. The US Marines, Coast Guard, and Army Air Corps refused to enlist black troops while the US Navy relegated black sailors to service positions until after Pearl Harbor. After the attack, these branches often assigned black servicemen to labor positions such as cook or cargo loader.

Emblematic of the mentality of the armed forces at this time, the Red Cross recorded the race of blood donors. Military officials segregated “white” and “black” blood, even though scientists and medics alike understood that plasma and blood cells did not recognize their arbitrary categories of race. The NAACP waged a campaign of education that ended this practice, as well as ending some instances of segregation on military facilities. Most campaigns for equality were aimed at increasing the number of black officers while calling on each branch of the military to create or expand black combat units. The most famous of these units were the Tuskegee Airmen and the 761st Tank Battalion, which are detailed in a later section.

The most historic change to the armed services during the war was the authorization of female service, first as civilian members of a women’s army auxiliary in 1942 and then as officers and enlisted women entitled to military pay and benefits. Women had worked for the military in World War I as civilians performing many of the same tasks as enlisted men in various noncombat positions. The navy even enlisted 13,000 women to perform these duties during that war, an action that quickly prompted Congress to amend its laws regulating enlistment by adding the word “male” as a requirement instead of an unwritten assumption. Wartime necessity and the activism of women led to the creation of the Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps (WAAC)Proposed by Congresswoman Edith Nourse Rogers prior to the attack on Pearl Harbor but not approved until May of 1942, the WAAC enrolled women as civilians to work with but not in the army. It was replaced by the Women’s Army Corps in 1943, which granted women full military status. Approximately 150,000 women joined the WAAC and another 75,000 women served in the nursing corps of the various armed services. and the Women Accepted for Voluntary Emergency Service (WAVES) of the navy, as well as other women’s units.

The use of labels such as “voluntary emergency service” and “auxiliary” connote the ways the military tried to qualify its acceptance of female members. However, the navy granted women the status of military members, and the army changed the name of its female branch to the Women’s Army Corps (WAC) when its members were granted military status in 1943. Some 350,000 women served in the military as noncombatants filling “female” jobs in clerical and nursing fields, but many also served as mechanics and other traditionally “masculine” jobs. Other units repaired weapons and radios, while a small number of women on the West Coast instructed male pilots how to use their navigational equipment. Nearly 1,000 women flew cargo planes and towed targets for live antiaircraft drills as part of the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP). Despite the danger of their job, which led to the mission-related deaths of over three dozen women, the WASPs were denied military benefits and veterans’ benefits.

The women stationed at these pilot-training facilities in California contributed to the rapid growth of West Coast cities. Military contracts doubled the size of cities such as Albuquerque, while naval bases doubled the already rapidly expanding population of San Diego. Hundreds of small and middle-sized towns throughout the country experienced wartime booms as nearby soldiers flooded area towns to spend weeks of earnings before their leave expired. The recreational ambitions of some soldiers inspired Congress to pass the May Act in 1941. The law granted military officials the power to close businesses and even restrict entire cities from military personnel if local authorities did not satisfactorily combat prostitution. As a result, more than seven hundred US cities closed down their red-light districts while military police (MP) and the navy’s shore patrol watched over vice districts near military installations.

Figure 8.8

This college-aged member of Women’s Army Corps (WAC) repaired aircraft during World War II. She also had a pilot’s license. Other women with similar credentials served as civilian pilots in the Women’s Air Force Service Pilots (WASP) program.

Soldiers on leave were required to wear uniforms so that MPs could easily spot military members and regulate their behavior. Servicemen sought to evade these restrictions by utilizing underground “locker clubs” that rented civilian clothes and secured a serviceman’s dress uniform until he was ready to return to base. While the behavior of female service members was heavily scrutinized, the military tolerated a certain degree of rule breaking by men on leave. However, one of the businesses that military authorities were especially vigilant in patrolling were bars known to cater to homosexual men.

Although the US military had a long history of discharging soldiers convicted of homosexual acts, World War II saw the first significant attempt to prevent homosexuals from entering the armed services. All potential enlistees were required to undergo brief psychological examinations that included questions about their sexual orientation. The military interviewed 18 million potential service members but only disqualified 4,000 to 5,000 potential enlistees for homosexuality. Historian Allan Berube has demonstrated that this low number was the result of gay men becoming well accustomed to hiding their personal life during this era. For example, Berube has even found that the celebrity musician Liberace was drafted and only disqualified because of a physical injury.

Homosexual men had learned to mask their sexual orientation and casually answered the questions about their attraction to women as heterosexual men were expected to answer them. Few of the 350,000 women who served in the military were directly questioned about their sexual orientation, largely because women’s service branches were already battling stereotypes about female soldiers being both unfeminine and sexually aggressive—both characteristics stereotypically attributed to homosexual women. Despite limited attempts to prevent gay servicemen and women from joining the ranks, historians estimate that between 300,000 and 1.2 million of the nation’s 15 million women and men who joined the armed services during World War II were homosexuals.

These attempts can accurately be described as limited because most Americans assumed that young men and women deemed fit for service were heterosexual. In addition, the top priority of military psychiatrists was not to screen against homosexuality, but rather to identify those most likely to become psychiatric casualties. Military officials believed proper screening could greatly reduce the number of these psychiatric cases, which accounted for half of the patients in veterans’ hospitals twenty years after World War I. Military necessity likewise drove the informal and often reluctant toleration of gay soldiers by their peers and commanders. In 1940 and 1941, most reported cases of homosexuality led to trials and imprisonment. However, by 1942, most of these men were quietly discharged from the service or simply transferred to another unit. After 1942, most commanders, especially those on or near the front lines, were informally counseled to try and “salvage” those under their command who were known to be homosexual, as long as their lifestyle and behavior did not “threaten” others. As one combat medic in the Battle of the Bulge recalled, “No one asked me if I was gay when they called out Medic!” Thousands of openly gay men and women served during World War II, although the vast majority continued to hide their sexual orientation. Among this group were future celebrities such as Rock Hudson, recipients of the Navy Cross and Silver Star, and dozens of high-ranking officers. Gay veterans recall service to their country as their leading concern. For many others, the war was a personal quest against the forces of persecution and intolerance. For gay Americans and the hundreds of homosexuals who fled Europe and enlisted in the US armed forces, the brutal murder of homosexuals in Nazi concentration camps inspired their distinguished service.

Republican congresswoman Edith Nourse RogersA Massachusetts congresswoman who served her district from 1925 to 1960, longer than any woman in history. During her time, she sponsored not only legislation benefitting women, such as bills ensuring that women serving in military positions were granted military status and benefits, but also legislation benefitting all veterans such as the GI Bill. of Massachusetts introduced a bill authorizing the creation of a Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps (WAAC) in May 1941. Nourse was motivated by her desire to obtain military benefits for the nearly 60,000 women who were already performing the same job as male soldiers in a variety of clerical and other fields. These women were hired by the military, but because they were not in the military, the women were ineligible for benefits and often paid far less than male soldiers.

Rogers’s bill passed in May 1942, by which time each branch of the armed services was creating similar opportunities for female service. For example, the navy organized the Women Accepted for Voluntary Emergency Service (WAVES)The women’s branch of the navy during World War II. Unlike the army, the navy immediately recognized women who joined the WAVES as members of the military. Some 100,000 women served within the WAVES of the navy, while another 40,000 served in the marines and coast guard. Approximately 75,000 women served in the nursing corps of the various armed services. in August 1942. One important distinction between the two organizations is that women in the WAVES were part of the navy, while the WAACs were considered civilians until 1943. At this time, the WAAC became the Women’s Army Corps (WAC)Begun as a civilian auxiliary to the all-male army, the Women’s Army Corps enlisted 140,000 American women who served in various noncombat positions ranging from clerical work to mechanical and communications fields., and like the WAVES, WAC members held the same rank and were given the same pay as men. In practice, however, few women were granted promotion past the lowest enlisted ranks. The result was the continued discrimination against women in terms of rank and pay that was typical in civilian employment.

This inequity in promotion was related to the military’s perception of female service as an “auxiliary” to the more important work of male soldiering. Most women at this time at least partially accepted the notion that women’s service was secondary to that of men. Even women who had more radical ideas about gender usually sought to convince others that female military service was consistent with more widely accepted views about women’s roles. For example, Americans viewed British women serving in their nation’s various military auxiliaries as heroines forced from their homes by the extraordinary threat of invasion. Americans generally admired the way the British women responded to their nation’s call for service and recognized that total warfare required full mobilization of all resources. As a result, advocates of female service in the United States argued that the emergency of war made it permissible for US women to temporarily serve in military roles, just as women in Britain had done.

The public reaction to women’s service was skeptical at first, as evidenced by letters to the editor of hundreds of local and national newspapers that questioned the likelihood that women would be effective as soldiers. These letters frequently contrasted the “male” characteristics of discipline, intelligence, and strength with the belief that women were naturally disposed to be overly emotional, illogical, chatty, and obsessed with trivial things like shopping. Others predicted that women’s service would lead to a breakdown of the home as well as military discipline. Over time, these objections became less frequent, especially as military officials embraced the idea of women’s service and praised the efforts of early recruits.

Despite the nation’s growing acceptance of female soldiers and sailors, Americans also reveled in political cartoons, which played on their earlier assumptions that women and military service were incompatible. Newspapers produced hundreds of images of women falling in for revile in curlers, struggling to salute an officer while holding a purse, and falling behind on a march due to high heels and a pesky slip that kept showing underneath their military-issued skirts. Popular cartoons such as Winnie the WAC featured the misadventures of an affable but stereotyped blonde who daydreamed about shopping and men while her more serious and soldierly brunette and red-haired bunkmates adjusted easily to army life. These cartoons may have seemed both humorous and good-natured to many readers, especially considering the many mean-spirited portrayals of WACs as unattractive, unpleasant, and unfeminine. Other artists simply poked fun at their society’s fears that female service would reverse gender roles. A popular cartoon sarcastically featured the new model of American masculinity at home in an apron, knitting while pining away for his wife as he waited for his protector and provider to send him his monthly allowance as a military “wife.”

Surveys of public opinion demonstrate that these cartoons were popular because most Americans reconsidered their initial concerns about limited wartime service leading to the breakdown of traditional gender roles and at least tentatively approved of women serving as WAVES, WAACS, military nurses, and other female service branches. Addressing these initial concerns was the leading task of many advocates of female service, such as Ohio congresswoman Frances Bolton. Bolton and other women worked to minimize the potential threat female service might represent to some men. Women were not joining the military to compete with male soldiers, Bolton explained, but rather assist them with their job of protecting the country during wartime. If the presence of women in nursing and secretarial positions in the civilian sector was considered acceptable work, women asked, why should they be barred from performing these same tasks in the military? The military would still be “a fighting world for you,” Congresswoman Bolton assured her male listeners, “and an assisting one for us.”

Figure 8.9

Many images from this time period poked fun at the notion of women in the military. Winnie the WAC featured an affable but stereotypical “blonde” whose comical misadventures also poked fun at the army’s inclusion of women.

Bolton and other proponents of women’s service stressed that female enlistment provided a means by which thousands of male soldiers could be “freed up” to serve in combat operation, just as female factory workers had permitted more men to join the military. Declining enlistments motivated even the most conservative male military leaders to consider this point of view. By 1942, each branch of the military launched a propaganda campaign aimed at convincing Americans that women’s service was not a radical departure from other modes of female employment. For example, one poster juxtaposed the image of a civilian woman taking the place of a man on an assembly line with a military woman taking place of a male soldier at a typewriter. In both instances, the man in the poster seemed taller and stronger as well as more confident and happy as he abandoned “women’s work” and assumed his proper masculine role as a soldier on the front lines. Such wartime propaganda helped to win support for women’s service. However, these images likely had a debilitating effect on the hundreds of thousands of male soldiers employed in clerical and service positions.

Eleanor Roosevelt took a slightly more radical view of women’s military service. Roosevelt was an early proponent of the WAAC and worked to secure her husband’s support for a number of suggestions she sent to the War Department throughout 1941. After years of work to convince military leaders of the usefulness of female enlistment and its consistency within traditional notions of gender, female service advocates launched offensive campaigns of their own against those who opposed their ideas. Armed with the full support of military leaders, women’s rights advocates were able to place opponents of female service on the defensive. Wrapping “GI Jane” in the flag, women’s service advocates challenged the patriotism of those who still opposed female service in the later years of the war. If every woman who joined meant that one more rifleman could serve on the front, they asked, how could any loyal American still oppose female enlistment?

Advocates of women’s military service also presented wartime service as a way patriotic women could aid the war effort, utilizing emotional images such as sisters and wives of deceased veterans honoring fallen brothers and husbands through their service. By placing opponents of female service on the side of America’s enemies, these women engineered a reversal of fortune where opponents of female service were now placed on the defensive. For example, one congressman who opposed women’s service complained that he and others would not dare vote against measures to expand women’s service for fear of being accused of hindering the war effort.

Women’s rights advocates were also able to turn paternalistic arguments about the need to “protect” women against those who opposed equality in the ranks. If the men who opposed granting full military status to women were acting out of concern for these women, they asked, why did those men insist that women work the same clerical jobs as male soldiers but be denied the protection of veterans’ benefits? Over time, most Americans recognized the valuable service women provided and supported the decision of each branch and the War Department to grant women full military status and benefits such as the GI Bill. However, many hoped that after the war was over, the military would return to the status quo with women working as civilians for the military rather than soldiers and sailors within it. They feared that changing the military’s institutional gender structure would forever alter society’s ideas of masculinity and traditional gender roles. Men were expected to fight as part of their role as defenders of the nation and the home according to this traditional model. Under this ideal, women were expected to support the men and play the role of the girl back home for whom each man was fighting. Female soldiers reversed the traditional image of women as the recipient of protection and likewise threatened to challenge the notion of men as protectors. For this reason, many hoped that female membership in the armed services would be limited to the war years.

The notion that women’s service would be a temporary expedient originated from the initial arguments of women such as Edith Nourse Rogers. She and others who led the fight for female service were radical in their acceptance of women as members of the military who should receive equal pay and benefits. However, many of these women also accepted notions of female service as temporary, separate, and subordinate. Most advocates utilized conventional notions of gender as they tried to win over opponents, assuring them that women would be only temporary workers in auxiliary positions in a chain of command that ultimately reported to male leaders. These women generally avoided any argument that likened women’s service to women’s rights, and few would have considered themselves as feminists, at first. However, the service and sacrifice of 150,000 WACs, 100,000 WAVES, nearly 40,000 women within the marines and coast guard, and 75,000 military nurses convinced women’s advocates and military authorities to agree that women’s service was instrumental to the war effort and should continue. In 1948, Congress passed the Women’s Armed Service’s Integration Act, authorizing female service in all branches of the military during both peacetime and war. However, negative perceptions of female service remained long after women were permanently integrated into the military.

Figure 8.10

Japanese American families awaiting baggage inspection upon arrival at an assembly center located near to the present-day campus of California State University–Stanislaus in Turlock, California.

The attack on Pearl Harbor and subsequent US defeats spread fear along the West Coast. For Japanese Americans, the news of Pearl Harbor produced a different kind of fear. In addition to sharing the concerns of their countrymen regarding the impending war and those who had lost their lives, they also feared the discrimination they had endured would now take the form of violent retribution for the attack. The FBI immediately conducted mass arrests of Japanese newspaper editors, civil rights and community leaders, even Buddhist priests. Within weeks, the government expanded its dragnet from leaders of Japanese organizations to all persons of Japanese ancestry convinced that the Japanese military were planning additional attacks with the assistance of informers within the United States. Even worse, many Americans and government officials believed that if Japan launched a full attack on the West Coast, most American residents of Japanese ancestry would welcome the invaders and take up arms against their former countrymen.

The FBI also arrested over 10,000 immigrants from Germany and Italy for similar reasons, but these investigations were based on suspicion of membership within pro-Nazi and fascist organizations, unlike the Japanese, who were arrested for association within a Japanese community organization or Buddhist church. Given the millions of Americans of Italian and German descent scattered throughout the nation, there was hardly any consideration of investigating or detaining these groups. In contrast, Japanese Americans were a much smaller minority who tended to live within 100 miles of the West Coast. Italians and Germans continued to face discrimination in America, but decades of migration combined with the common European heritage of other Americans had eroded most of the hostility these groups faced. In contrast, Japanese Americans in 1940 experienced the same racial prejudice that had led to laws restricting their entrance into the nation, including stereotypes that suggested that the Japanese were deceptive by nature. As a result, the military forced 120,000 Japanese Americans to live in detainment camps. Most of the detainees would remain in these camps for the duration of the war.

President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066Issued by President Roosevelt in 1942, Executive Order 9066 granted the military the authority to remove persons of Japanese descent from the West Coast. The order also led to the arrest of 5,000 Italian and German immigrants. However, the order was primarily aimed at Japanese Americans and led to the legal internment of an estimated 120,000 people in camps from Arkansas to the West Coast. on February 19, 1942, authorizing the military to designate sections of the country from which “any and all persons” might be removed. The law did not specify what everyone already understood—that this was a measure granting wide authority to officials in the War Department to force Japanese Americans to leave the West Coast. A number of Roosevelt’s advisers believed that the plan was a clear violation of the civil rights of US citizens of Japanese descent and unjustified because despite the mass arrests, not one person had been proven guilty of treasonous crimes. Roosevelt instead chose to follow the advice of his military leaders and accommodate the demands of numerous West Coast politicians who aroused the angry passions of anti-Japanese prejudice in demanding the immediate removal of all persons of Japanese ancestry no matter their age, gender, or length of time as US citizens. Rumors that dozens of Japanese pilots who participated in the raid on Pearl Harbor had been US citizens were reported as fact. Americans were also surrounded by false reports that Japanese residents of Hawaii had worked behind the scenes to prevent early detection of the raid. Surrounded by fear and misinformation, few Americans questioned the military necessity of detainment or challenged the assumption that anyone of Japanese descent should be considered a suspect.

The government’s removal and detainment of Japanese Americans followed a three-step process. At first, the military simply ordered Japanese Americans living on the West Coast to migrate east on their own and at their own expense. Voluntary relocation failed because few Japanese Americans agreed to leave and because residents and political leaders of various Western states protested that this would simply make their communities “vulnerable” to Japanese treachery. The government then served notice that all Japanese Americans must register and prepare to be sent to a variety of “assembly centers” operated by the War Relocation Authority (WRA). Few had more than a week to prepare for this second phase of relocation, and as a result, many were forced to sell homes and businesses for a fraction of their value. After arrival at one of eighteen assembly centers, usually fairgrounds surrounded by barbed wire where internees slept in horse stalls, people were forced to wear luggage tags indicating the internment camp to which they would be sent. Transfer to one of ten camps marked the final step of the process.

Figure 8.11

The Hirano family was among the 18,000 people sent to the Poston, Arizona, internment camp. They are pictured here with a photo of a family member who served in the military. The Poston camp was located in the Sonoran Desert and was so isolated that guard towers were not constructed, although the camp was surrounded by fences.

Life in the internment camps was difficult, especially for the first arrivals in May 1942 who found that their new homes were not yet ready for habitation. Internees were tasked with building their own camps, even building watchtowers and repairing the barbed wire that surrounded them. Most internees lived in camps in the deserts of California, Utah, and Arizona where temperatures varied from well over 100 degrees to below freezing in the same month. Others lived in swamp-like conditions near the Mississippi river or other inhabited lands. They also faced military discipline including strictly regimented schedules and inspections, a near total lack of privacy, and the arbitrary justice of armed soldiers who guarded the camps. Despite the conditions and injustice that led to their internment, Japanese Americans joined together to improve the quality of life within the camps. Of particular importance were schools, cultural activities, and recreation. Traditional Japanese sports alternated with basketball and baseball, a game played by generations of Japanese immigrants in California. Internees at the Gila River camp in Southern Arizona constructed a modern ballpark and formed several different leagues under the direction of California Kenichi Zenimura, a baseball legend who had once played with Babe Ruth; Zenimura had been detained with his family in the camp. The camp’s top teams competed against and defeated army teams, as well as local high schools and colleges.

Most Americans defended this practice as vital to the defense of the nation and denied that the measure was the result of racism. African American leaders were among the strongest critics of relocation as a denial of civil rights. Native Americans shared a unique perspective as the victims of centuries of forced relocation and likewise challenged the alleged racial neutrality claimed by defenders of relocation. Others, such as General John DeWitt who administered the internment program, emphatically believed that race was the basis of the entire program. Dewitt’s original memo recommending removal referred to the Japanese as “an enemy race.” When questioned about why no person of Japanese ancestry had been found guilty of disloyal acts in the months that followed Pearl Harbor, he insisted that this fact merely confirmed the treachery of the Japanese, who, he contended, were simply hoping America would lower its guard. “I don’t want any of them (persons of Japanese ancestry) here,” he exclaimed to Congress. “They are a dangerous element.… There is no way to determine their loyalty.… It makes no difference whether he is an American citizen, he is still a Japanese…but we must worry about the Japanese all the time until he is wiped off the map.”

Thousands of Japanese Americans protested their internment from within their camp walls. The strategies they utilized varied from those who sought to demonstrate their loyalty by volunteering for military service to those who renounced their citizenship. Others followed the precedent of Native Americans by protesting forced relocation in dozens of court cases. In Korematsu v. United StatesA US Supreme Court Case in late 1944 in which the Court declared that the internment of Japanese Americans was justified to protect national security. Three of the nine justices dissented, viewing internment as a form of racial discrimination and a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment., the Supreme Court upheld the legality of Japanese internment under the Fourteenth Amendment on December 18, 1944. The court declared that the WRA had not singled out the Japanese American defendant Fred KorematsuThe son of Japanese immigrants, Korematsu was born in Oakland at the end of World War II. He refused the government’s order to report to a relocation center and was arrested and jailed. With the assistance of the American Civil Liberties Union, Korematsu appealed his arrest all the way to the Supreme Court, which determined in 1944 that the internment order was justified by the existence of Japanese American spies. Provided with new information detailing the absence of any Japanese American spies, however, a federal court reversed Korematsu’s conviction in 1983. because of his race and that the exclusion of Japanese citizens from the West Coast was legal. In a second case decided on the same day, the court limited the powers of the War Relocation Authority to detain citizens whose loyalty to the United States had been proven. The wording of this second decision was intentionally vague, allowing the government to selectively release some internees long after Japan’s ability to attack the United States had been eliminated.

Like other minority groups before them, Japanese Americans used logic and moral suasion to demonstrate that the discrimination they faced hurt the war effort. Among the many letters and petitions calling for their release were detailed estimates of the total cost of relocation in contrast with the potential contribution Japanese Americans could make to the war effort. Others pointed out the propaganda value the WRA provided the enemy in convincing Asian peoples to support the war effort against the Unites States. Japanese American leaders also sought to make Americans question their leaders’ assurances that detainment was needed to protect their safety. If Japanese were such a threat, they reasoned, why were only a few thousand of more than 100,000 persons of Japanese descent in Hawaii detained? Hawaii was the most likely and most vulnerable target, yet the military continued to employ thousands of Japanese who were not US citizens on the very military bases that were so vital to the nation’s defense. Had military officials responded to these letters, they would have tacitly admitted that these bases could not operate without the employment of persons of Japanese descent, who represented a third of the islands’ population. That persons of Japanese descent continued to work on military bases throughout the Pacific while only a handful of people were ever convicted of spying for the Japanese (most of whom were Caucasian) became a powerful argument to force Americans to reconsider internment.

More than 30,000 Japanese Americans joined the war effort, the majority of whom had been forced from their homes following the attack on Pearl Harbor. Several hundred internees refused induction into the military and were soon transferred from detainment camps to prison. Those who chose to serve the nation that had detained their families joined regiments such as the 100th Battalion, which had been created earlier in the war. Prior to the inclusion of the internees, the 100th Battalion consisted primarily of second-generation Japanese who lived in Hawaii. More than 1,000 young men who were detained on the West Coast volunteered for service in late 1943 when given the opportunity and joined the 442nd Infantry Regimental Combat TeamAn all-Japanese American unit composed of men who had joined the military prior to the attack on Pearl Harbor that was augmented by recruits who had been living in internment camps throughout the West Coast and volunteers from Hawaii and other areas. The 442nd served with distinction in military campaigns throughout Europe, including the liberation of the Dachau concentration camp.. Together, the 14,000 men who served within this unit became some of the most highly decorated soldiers in US military history, earning more than 9,000 Purple Hearts. More than 700 Japanese American soldiers were declared missing or killed in action. The medals earned by these men were delivered to surviving family members, many of whom were still detained as “enemy aliens.” Military service did not exempt one’s family from internment, and so hundreds of soldiers of various backgrounds whose spouses were of Japanese origin also fought to defend a nation that detained their families.

For the 80,000 Americans of Chinese descent and the more than 100,000 who migrated from Korea, Vietnam, the Philippines, and other nations in Southeastern Asia, the attack on Pearl Harbor meant that their new home was now allied with their ancestral home against the Japanese. California residents of Filipino origin were especially motivated to defend both their homelands and formed two regiments of infantry. Thousands of other Filipinos served in various “white” regiments. Women such as Hazel Ying Lee, who had been trained as a pilot in China, flew civilian missions for the army before a mechanical failure caused a crash that ended her life. What might have led to greater acceptance of these Asian Americans and immigrants quickly turned into a nightmare as few white Americans made any effort to distinguish between people of various Asian ancestries. Tens of thousands of Asian Americans from China, Korea, and the Philippines joined the military, yet they and their families faced anti-Japanese taunts from a racially charged and misinformed public. Civilians wore Chinese flags or placed signs in their shops identifying their Korean ancestry to little avail. Even participation in anti-Japanese race-baiting did little to convince some whites that an individual was not simply masking his or her true ancestry and loyalty. Tragically, hundreds of American citizen-soldiers of various Asian ancestries learned that their families had been the targets of racially motivated crimes in letters they received while enlisted in the US military.

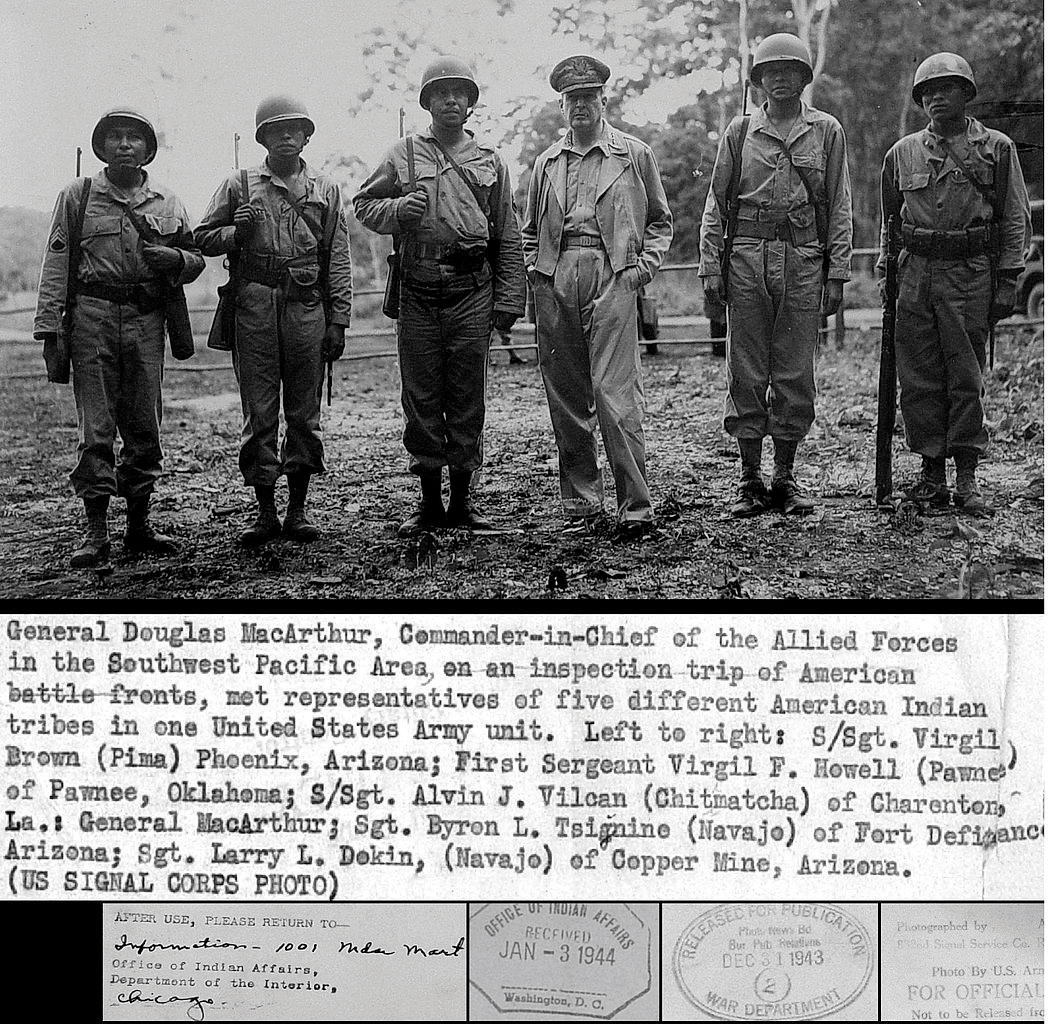

More than 25,000 residents of Native American reservations and another 20,000 Native Americans enlisted in the US armed services, a number representing nearly a third of those native men who were eligible to enlist. The Six Nations (also known as the Iroquois Confederacy) issued their own declaration of war against the Germans and Japanese. This action both demonstrated support for the American cause and emphasized the principle of Native American sovereignty and the importance of tribal governments. Just as the Choctaw had sent secret messages during World War I, Native American soldiers in World War II demonstrated the value of their cultural traditions by using their languages to send messages to one another. Navajo members of the Marine Corps are the most famous example because their complex language was understood by only a handful of non-Navajo people in the world. This complexity allowed the Navajo Marines to speak freely to one another over radio channels with little fear of the enemy deciphering their messages.

These Code TalkersA generic term referring to Native Americans who utilized their indigenous languages to communicate top-secret messages for the US military during World War II. The term usually refers to Navajo members of the marines operating in the Pacific whose ability to speak directly with each other without the time-consuming use of encryption machines gave US commanders the advantage of nearly instant communication without fear of the enemy intercepting their messages., as they became known, adapted many of their words to represent terms used during modern warfare as they sent secret messages on behalf of Allied commanders. For example, “iron fish” represented “submarine,” while individual locations could be spelled out with their own unique version of a phonetic alphabet. The Navajo language does not consist of a formal alphabet, so the code talkers would use Navajo words whose English meaning corresponded with the first letter they were trying to communicate. For example, if a code talker wanted to communicate the word “Japan,” he might say “jacket-apple-planet-ant-night.” German and Japanese intelligence officers knew that the military was once again using indigenous American languages as code, but failed in their efforts to recruit a single member of any of the tribes whose languages were used as code.

Figure 8.12

General Douglas MacArthur is pictured with members of a unit composed entirely of Native American soldiers. The five troops in this photo are each from different tribes and locations throughout Arizona and Oklahoma. In this way, the unit was both segregated and a melting pot for people of diverse backgrounds.

The 1930s were host to a number of programs aimed at restoring Native American culture, language, history, and community life within the reservations. The code talkers and the large number of well-educated young men and women who entered the military demonstrated the value of these programs. Yet these individuals and the tens of thousands of others who left the reservations to take wartime jobs in the nation’s cities were a bittersweet pill for those seeking to restore native life and culture. The demands of the war reduced funding for further cultural and educational programs, while many of the would-be reservation leaders of the next generation enlisted or found wartime jobs in large cities. Many native veterans decided to take advantage of their military benefits to attend college, and some of these young folks decided to take better-paying jobs in cities throughout the country. The success of these individuals seemed to many Americans as evidence that other natives must also be “liberated” from the reservations. In the next decade, many Americans supported plans designed to close reservations in hopes of completing the process of assimilation. Most of these advocates had positive intentions, but many demonstrated a lack of respect for the agency of native people by their failure to consider the opinions of natives regarding plans for the termination of reservations.

Military enlistment and the migration of millions from farms to cities created an emergency labor shortage for US farmers at the exact moment the nation needed to increase food production to feed its army and allies. After a decade of discouraging Mexican immigration during the Depression, the federal government now requested assistance from the Mexican government to help the US farmers recruit agricultural laborers. The Mexican government was skeptical of US intentions and worked to gain assurances that Mexican nationals working in US fields would be treated fairly and not drafted or otherwise coerced into military service. The government responded in 1942 by creating the Bracero ProgramA federal initiative aimed at encouraging Mexican nationals to come to the United States as agricultural laborers on temporary contracts between 1942 and 1964., which recruited Mexican laborers in both agriculture and railroad construction to come to the United States.