The middle and late 1960s were years of progress, protest, prejudice, and renewed hope for peace and racial justice. John F. Kennedy was assassinated, as were Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr., and Robert Kennedy. The postwar economic boom continued throughout most of the decade. It was accompanied by heightened fears about the possible growth of Communism abroad and escalating protests at home. The United States had grown accustomed to interpreting the events at home and around the world in terms of the Cold War. In addition, US officials were growing increasingly frustrated with the persistence of Communist forces in Vietnam in the face of military escalation. A growing number of Americans were likewise frustrated by the persistence of poverty and racial injustice. They pressed the federal government to approve meaningful laws and programs that would fulfill the promise of justice and material security. Modern feminism emerged as a force for change, along with the American Indian Movement and activism by other minority groups. Promising a Great Society, President Lyndon Johnson hoped to respond to these demands and promote greater freedom through government. In response, a growing conservative movement revived longstanding traditions that viewed the growth of the federal government as the greatest threat to liberty.

In 1963, President John F. Kennedy (JFK) once again enjoyed high approval ratings. The economy was prospering, and the ill-conceived Bay of Pigs Invasion was all but forgotten in the wake of Kennedy’s successful posturing in Berlin and the resolution of the Cuban Missile Crisis. Kennedy even began to support the limited civil rights initiatives he reluctantly inherited. At the same time, he sought to distance himself from some liberals who desired greater changes than he believed would be politically advantageous to support. His mild support of causes that were unpopular at the moment—such as civil rights—would later be among his most vaunted achievements.

The president’s admirers claim that Kennedy would have done more to support meaningful federal intervention to defend civil rights had he not been assassinated in 1963. Some also believe he would have supported the withdrawal of US troops from Vietnam. During his lifetime, Kennedy was restrained by political calculations in these regards. Privately, Kennedy responded to those calling for withdrawal from Vietnam, more support for civil rights, and more aggressive backing for health care reform with the promise that he would address these issues once he had secured a second term.

It was in pursuit of that second term that led Kennedy to Dallas in November 1963. Texas Democrats were in the midst of a political civil war regarding issues such as civil rights. To demonstrate his leadership and ensure his reelection, Kennedy hoped to unite Democrats in one of the most conservative states. He succeeded in this goal but only by becoming a martyr. On November 22, 1963, President Kennedy was shot while parading through Dallas in the back of an open limousine. He was pronounced dead a half hour later in a Dallas hospital. News of the tragedy spread instantly throughout the nation. For the first time, most Americans turned to television news anchors rather than newspaper reporters for information about a major news story. Not only did this result in a deluge of dramatic images but also in a number of reports filed in haste as some of the live television reports featured more speculation than fact. Conspiracy theories spread rapidly in living rooms across the nation as reports about the accused assassin Lee Harvey Oswald circulated. Oswald had planned on traveling to Moscow, leading some Americans to expect that the assassination had been part of a Communist plot.

Figure 11.1

Kennedy’s vice president Lyndon Baines Johnson being sworn in as president immediately following the Kennedy assassination.

The nature of live television also provided a degree of reassurance that the mechanism of government would continue to function. Millions watched as Vice President Lyndon Johnson took the oath of office while the widowed Jackie Kennedy stood in the background, still wearing a dress that bore the stains of her late husband’s blood. The capture of Oswald might have closed the case. However, live television again recorded a killing related to the Kennedy murder. Dallas nightclub owner Jack Ruby jumped out of a crowd and shot Oswald while he was being transferred from one jail to another. Oswald died less than an hour later.

Kennedy’s death left Americans with a sense that his vision for the United States might be left unfulfilled, even if few Americans agreed on what that vision entailed. Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren led a six-month investigation, concluding that Oswald had acted alone in killing the president. Many Americans were unconvinced by the Warren committee’s report. Even if they disagreed about the circumstances surrounding the Kennedy assassination and the direction the country was headed, Americans agreed that the system of government established by the Constitution was durable.

Throughout history and especially during the 1960s, presidential assassinations usually resulted in chaos and turmoil, perhaps even civil war. In the United States in 1963, the presidency was quietly transferred to former Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson (LBJ) according to the terms set out by the Constitution. As president, Johnson invoked the memory of the slain leader in support of the most significant civil rights legislation since Reconstruction. He also secured passage of Medicare and Medicaid, two federal government–sponsored health care programs for the elderly and the poor. Despite these significant domestic achievements, Johnson’s bid for more sweeping reform and possible reelection would be derailed by a seemingly endless war in Southeastern Asia. For Democrats, it seemed as if the history of the Korean War was repeating itself.

A New Dealer raised in the cutthroat world of Texas politics, Johnson was a lifelong and ambitious politician who suddenly saw himself elevated to the office he had coveted his entire life. The tragic circumstances that led to his presidency precluded celebration, however, and Johnson somberly accepted the challenge of healing the nation while quietly securing his nomination and victory in the upcoming 1964 election. For Johnson, the key to both was to portray himself as the successor to Kennedy while presenting his policies as the embodiment of the martyred president’s will.

Addressing Congress moments after the nation had laid its slain leader to rest, Johnson urged Congress to “let us continue” the work of the Kennedy administration. For Johnson, this meant that an assassin’s bullet should not derail the liberal consensus based on tax reduction, federal guarantees of civil rights, and antipoverty programs. Many who had once opposed the former vice president’s policies pointed out the unfairness of Johnson equating a martyred president with his own political agenda. At the same time, Johnson skillfully presented previously controversial measures such as the 1964 Civil Rights ActPerhaps the most significant piece of civil rights legislation in US history, the 1964 Civil Rights Act banned racial discrimination in public accommodations and employment. The law also outlawed gender discrimination and established a federal agency to enforce all of its terms. as a tribute to their fallen leader and the only proper response to an act of violence. As a result, in death, Kennedy became eternally connected to a civil rights bill he had only cautiously supported in life.

African American leaders recognized Johnson’s strategy and went along with the charade by eulogizing the former president in ways reminiscent of the historical memory of Lincoln. Civil rights leaders reminded Americans that JFK had promised to eliminate housing discrimination “with the stroke of a pen” while a candidate. In actuality, Kennedy had failed to act on his promise, which had prompted thousands of African Americans to mail pens to the White House to remind him of this promise. However, presenting civil rights as part of an unfulfilled agenda of a martyred president soon became an effective way to secure historic reform legislation.

Black leaders also pointed out that JFK had asked Martin Luther King to draft a second Emancipation Proclamation that he would sign on January 1, 1963, to mark the centennial of the original. Never mind, of course, that the president had also forsaken this promise and even failed to respond to the proclamation King had prepared for the president. Kennedy was a martyred hero, these civil rights leaders reminded themselves, and any connection between the former president and their cause must be promoted regardless of historical accuracy. Perhaps Kennedy would have supported the 1964 Civil Rights bill, they privately counseled one another; after all, the former president had recently addressed the nation on the issue against the counsel of his political advisers who feared any support for the proposed bill would cost him the election.

Figure 11.2

The organizers of the 1963 March on Washington lead the march in front of thousands of participants with signs calling for equal employment, voting rights, and the end of segregation. Each of the leading national civil rights organizations was represented on the program, and Martin Luther King Jr. was selected to speak last. Although women were often the most active organizers within these organizations, efforts to recognize their contribution were only belatedly added to the schedule of events.

Martin Luther King Jr. recognized that proposing a civil rights bill would not secure its passage in Congress. Even worse, presidents could claim to support the bill only to hide behind its failure each year. This would allow whoever occupied the White House to portray themselves as supporters of civil rights without actually securing any meaningful advances for black voters. King teamed up with veteran organizer A. Phillip Randolph and announced a march on Washington designed to force Congress and President Kennedy (who was still alive at the time) to support the bill. Approximately 300,000 Americans, two thirds of whom were black, converged on the nation’s capital for the March on Washington for Jobs and FreedomA 1963 protest that called on the federal government to pass sweeping civil rights legislation while also publicizing the lack of economic opportunity for African Americans. The march was a coordinated effort between the six leading civil rights organizations and is best remembered for Martin Luther King’s iconic “I Have a Dream” speech. in the summer of 1963. The protest was aimed at publicizing the need for antisegregation laws but also ensuring that all Americans would be given equal political and economic opportunity that would render such laws meaningful.

The march reflected the competing ideas of the six leading civil rights organizations that organized the march. Leaders of the Urban League and A. Phillip Randolph’s labor union spoke of the need for economic advancement, while younger leaders such as John Lewis of CORE were more controversial in calling for more radical change. The meetings also reflected the paternalistic orientation of these organizations; a brief acknowledgment of female leaders was only belatedly added to the agenda.

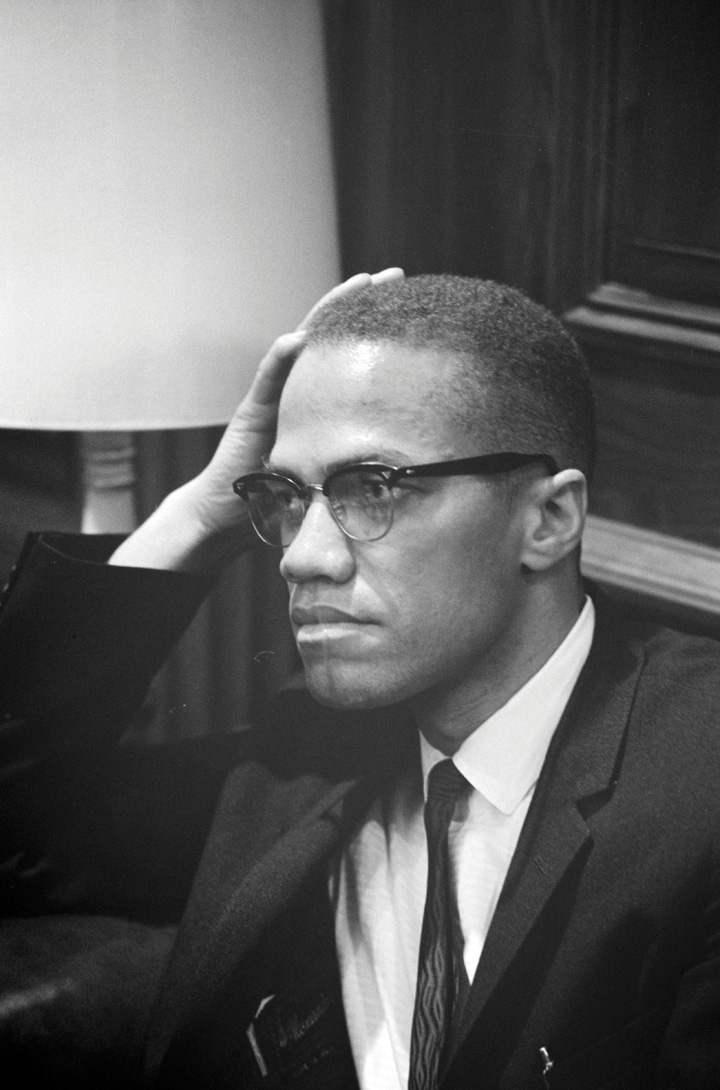

King was given the final spot on the schedule and rose to the stage after a brief announcement that W. E. B. Du Bois had passed away in Ghana. King then rose to the podium and delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech. King’s address remains an iconic moment in US history. It was also a moment where the mantle of leadership was symbolically passed from the generation of Du Bois to the charismatic young preacher from Montgomery, Alabama. Meanwhile, another young and charismatic clergyman named Malcolm XBorn in Omaha and raised in the Midwest, Malcolm X experienced many of the more subtle forms of discrimination that was common in the North. In prison, Malcolm joined the Nation of Islam and became the leading spokesman of the conservative black Muslim sect until his split with Elijah Muhammad in the final year of his life. criticized the March on Washington as a pep rally for sycophants and fools who believed they could promote meaningful change through the existing white-dominated system. The next Sunday, a bomb exploded during services in a black church in Birmingham, killing four little girls. In their memory, Democratic leaders and President Johnson rallied behind the 1964 Civil Rights Act the following year.

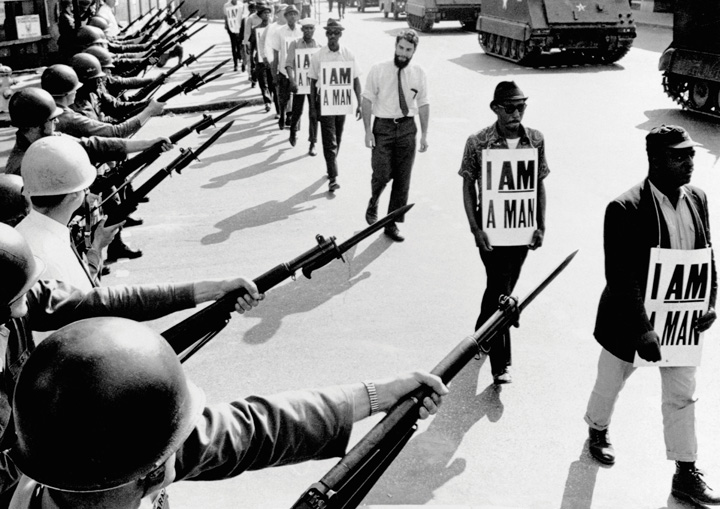

Figure 11.3

African Americans in Washington, DC, march in response to the bombing of a black church in Birmingham that killed four young girls. One of the victims was a childhood friend of future Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice.

Virginia congressman and segregationist Howard Smith proposed an amendment to the 1964 Civil Rights Act that added “sex” to the act’s existing provisions, guaranteeing equal opportunity in employment regardless of race, creed, color, and national origin. Because he and the other nine Southern congressmen who supported the amendment prohibiting gender discrimination strongly spoke in opposition to and voted against the Civil Rights Act, most historians believe that Smith’s amendment was intended to divide supporters and ultimately prevent the law from being passed. Smith understood that the majority of his peers now supported a law banning racial discrimination, but he believed that they considered gender to be a valid consideration among employers and would not pass the Civil Rights Act if it mandated equal treatment of men and women.

If derailing the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was indeed Smith’s intent, he was borrowing a strategy used by opponents of civil rights provisions dating from Reconstruction. For example, opponents of black suffrage in the 1860s added women’s suffrage to proposed laws that would have permitted black men to vote. These provisions led to the defeat of black suffrage before the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment, as well as the defeat of several civil rights laws throughout the twentieth century. In 1964, however, the Civil Rights Act was passed as amended, outlawing segregation while banning both racial and gender discrimination by employers. The act also created the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), which was charged with enforcing the terms of the new law.

One of the strongest opponents of the 1964 Civil Rights Act was Arizona Republican senator Barry GoldwaterA leading conservative and Republican nominee for president in 1964, Goldwater rallied those who believed the federal government was becoming too big and too powerful. Goldwater also opposed the 1964 Civil Rights Act, while personally claiming that he supported the goals of integration. Goldwater was defeated in a landslide in 1964 but continued to be a leading member of the conservative wing of the Republican Party.. Goldwater represented the conservative wing of the party and secured the Republican presidential nomination shortly after the Civil Rights Law was passed. As a result, the 1964 election was a clear ideological contest between the relatively liberal Johnson against the archconservative Goldwater. The author of Conscience of a Conservative, a best-selling autobiography that challenged images of the political right as reactionary and void of positive ideas, Goldwater hoped to reverse the growth of government in every way except national defense. As a candidate, he also promised to replace containment with a more aggressive strategy that would strangle and eliminate communism.

Figure 11.4

Arizona senator Barry Goldwater sought to distance himself from extremists such as these Klansmen who were demonstrating on his behalf during the election. However, his recent opposition to the Civil Rights Act of 1964 furthered the association between the conservative movement Goldwater represented and those who opposed racial equality.

Although many Americans equated conservative ideas, such as states’ rights, with the defenders of slavery and racial segregation, Goldwater sought to prove that conservative ideas had positive value for all Americans. He personally approved racial integration in schools but did not believe that the federal government had the power to “force” any state or locality to change the way it did business. More importantly, Goldwater predicted that such attempts would only harden racial prejudice and ensure that well-meaning attempts to integrate schools would fail in ways that harmed all children. For African Americans and many liberal whites, however, Goldwater’s advice to be patient and wait until whites of the Deep South sought integration was disingenuous at best. It also did not help that Goldwater had the backing of leading white segregationists such as Alabama governor George Wallace, who had proclaimed “segregation forever” the year before.

Other conservatives developed organizations and started journals such as the National Review in hopes of spreading their ideas. One of the leading conservative publications, the National Review, had originally supported white Southern intransigence to civil rights in terms that reflected support of white supremacy. By the mid-1960s, however, the journal began to be more critical of arch-segregationists and focused more on the issue of limited federal power. Among intellectuals, the political and economic theories of Friedrich Hayek united most conservatives and increasingly influenced moderates and even some liberals. Hayek posited that increases in governmental power, even under the best of intentions, would inevitably build upon one another until the government had grown so big and so powerful that it controlled nearly every aspect of life.

Other intellectual conservatives offered a spin on Marx’s view of historical progression to warn the United States that like other great powers, the US government was in danger of growing too big and squandering its resources at home and abroad. Liberals countered that conservatives only supported limited government when it came to social programs and actually favored increased spending for military and law enforcement. Conservative intellectuals continued to refine their ideas in ways that would lead to a conservative revival by the end of the decade. However, in the early 1960s, most Americans identified themselves as liberal. When these individuals imagined a typical conservative, conspiracy theorists like the John Birch SocietyA radical conservative organization that opposed the passage of the Civil Rights Act and viewed US participation in the United Nations as part of a radical conspiracy to lessen the sovereignty of the nation until the world was ruled by a single collectivist government. and militant white segregationists remained the dominant image.

Formed in 1958, followers of the John Birch Society believed they were ideological soldiers in a war against liberals, whose every move was calculated to bring the United States to its knees. By 1963, more than 100,000 Birchers spent much of their time writing letters to editors warning of the dangers of governmental programs and civil rights as harbingers of Socialism and interracial marriage. Even candidate Goldwater was not conservative enough for these on the extreme right, but he spoke to many of the Birchers’ fears that the Republican Party had been co-opted by liberals. Why else would President Eisenhower have permitted FDR’s programs to continue, he asked, while most leading Republicans in Congress acted as if they were running some kind of “dime-store New Deal”?

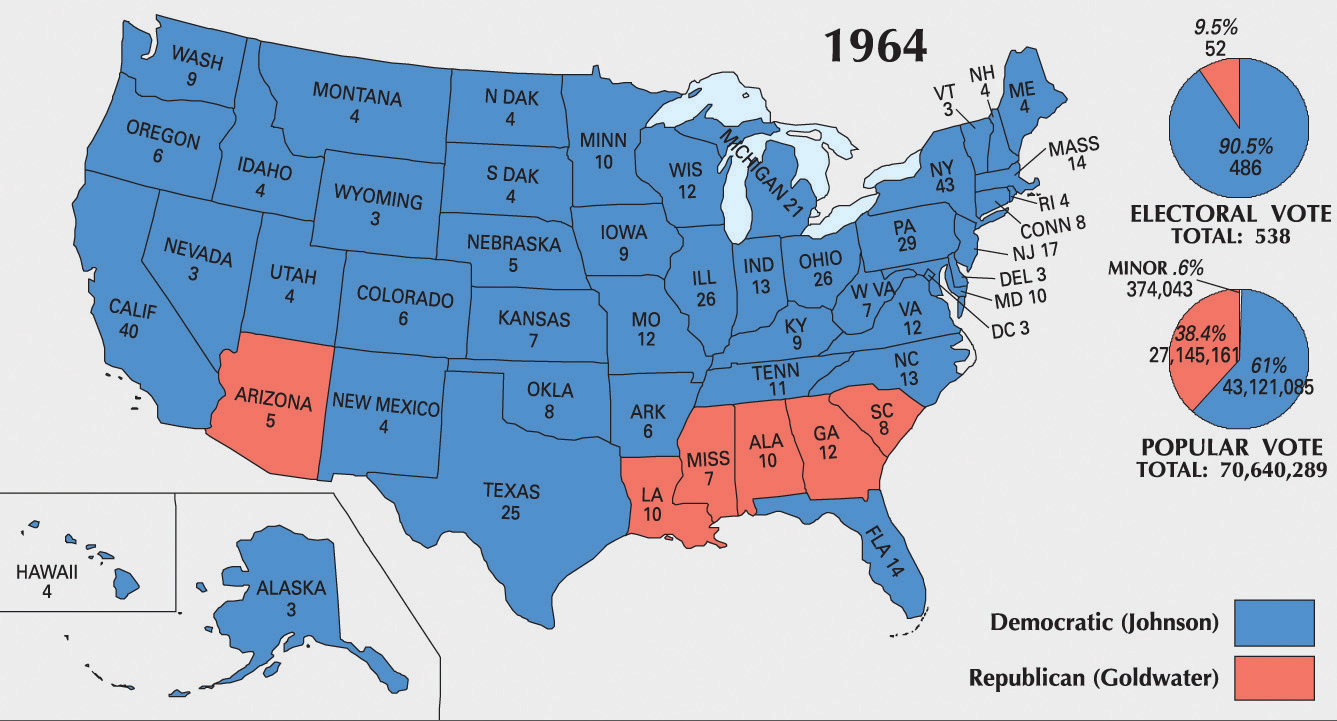

Goldwater not only spoke to the fears of many anxious whites who thought society was changing too quickly, but he also spoke without the usual politician’s filter. At times, this could be harmful. For example, speaking to a group of Midwesterners, the Republican nominee once asserted that the nation would be better off if the East Coast, a reference to Northeastern liberals, was severed from the nation and sent “out to sea.” The Democrats responded by running TV ads throughout the East that featured a cartoon saw slicing off the East Coast while Goldwater’s words played in the background. One of LBJ’s ads went too far by insinuating that a vote for Goldwater was a vote for nuclear armageddon. Although the ad was immediately recalled, Goldwater’s own rhetoric had created the notion that he lacked the patient temperament needed to be a leader of a nuclear power. Johnson won every state outside of the Deep South and Goldwater’s home state of Arizona.

Figure 11.5

Lyndon Johnson defeated the conservative Republican Barry Goldwater in 1964. However, conservative ideas would gain support following Goldwater’s landslide defeat.

Goldwater’s support among Southern whites from Louisiana to South Carolina was largely the result of LBJ’s support of legislation forever banning racial segregation. Because of this legislation, black Americans generally supported Johnson’s campaign even though they recognized that Johnson shared many of the racial assumptions of many whites. Legendary musician Dizzy Gillespie ran a mock campaign for president that trumpeted many of Johnson’s shortcomings. Gillespie promised to support the Democratic candidate when he finally offered genuine support for black Americans. Until then, the trumpet player campaigned promising to end the Vietnam War, poverty, and racial segregation. Gillespie’s America would be personified by his replacement of the White House with a “Blues House” where all Americans would be welcome. Gillespie also promised to appoint a number of prominent jazz musicians as cabinet officials and ambassadors, explaining his belief that the improvisational nature of jazz required individuals who intrinsically knew how to work with others to create harmony. The campaign raised money for civil rights causes, but it was more effective in reminding the Democrats that they needed to support civil rights initiatives if they expected the black vote in the next election.

One of black voters’ leading demands was that their local schools finally be required to comply with the 1954 Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education. The schools of Virginia provided a clear example that the federal government would have to intervene. After the schools of Virginia failed to integrate, black plaintiffs sued and won three separate victories as the federal courts ordered the integration of the schools in Warren County, Charlottesville, and Norfolk. In reaction, the Virginia governor ordered that all of the public schools in these districts close, and state officials required that any school district ordered to integrate must also close its doors. This strategy of thwarting integration at all costs, even if it meant closing schools for white children, was known as massive resistanceA term used to describe the various strategies employed by Southern whites to prevent school integration. Some of these strategies included passing laws mandating that schools be closed if forced to integrate.. In 1959, black plaintiffs in Prince Edward County, the same Virginia school district that had been home to one of the original five cases that were consolidated into Brown v. Board, sued in federal court. As had been the case in the other Virginia cases, the board was ordered to integrate. However, the all-white school board had already decided that it would close all of the county’s public schools if the appeal was lost. In addition, the federal courts had not yet declared that Brown v. Board applied to private schools. As a result, board members had devised a plan where public school resources would be used to create a number of “private” schools for white children.

The “privatization” of the Prince Edward County schools in the early 1960s demonstrated a new tactic available for advocates of massive resistance. Publicly owned schools were “leased” to individuals who hired the same white public school teachers to teach in what was now called a “private” school. Although segregationists were able to use a variety of methods to finance their schools with public money, the schools still required some tuition and private donations to function. As a result, many white children were also denied school privileges. As a form of denying racial discrimination, the school board suggested that middle-class African American parents open similar “private” schools for their children. While some black parents pursued this strategy with mixed results, others pointed out that doing so simply perpetuated segregation while shifting more of the financial burden for school funding on parents. Other black parents continued their fight in the courts until they secured a Supreme Court decision ordering the county school board to reopen and integrate the public schools. During the five years that the schools were closed, working-class white and black families drew upon networks of community and kin, pooling money and sending their children to live with out-of-state families.

Photos of angry demonstrations and even violence against the first black children to attend a particular school provide the most poignant images of school integration. However, the greatest obstacle to integration may have been waged by thousands of community groups that defended segregation with the demeanor of a local PTA meeting. Many of these organizations had progressive-sounding names that gave the appearance of defending children or promoting harmony. Others adopted names such as the White Citizens Council (WCC). Each of these groups devised methods to indefinitely postpone school integration through procedural delays, legal challenges, redrawing school boundaries, and creating integration advisory boards that never met.

Groups such as the WCC also sought ways to intimidate black leaders and isolate black families whose children were part of an integration lawsuit. WCC chapters were composed of city officials, business leaders, and middle-class white parents. Some chapters even received city and state tax dollars to fund their operations. The preferred tactic was usually nonviolent, convincing employers to fire any person known to favor integration. If an individual was self-employed, the WCC worked covertly to convince local banks to cut a family’s line of credit, even foreclose on mortgages that were in good standing to force integrationists to leave town.

While the WCC officially condemned violence, those black leaders and families that somehow continued their fight for integration were frequently the victims of drive-by shootings and arson. The year following the Brown decision, seven black leaders were murdered or went missing in Mississippi alone. In contrast to Border South states like Virginia and large cities such as Little Rock, few lawsuits were filed to try to force the integration of schools in Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia. Border South states such as Missouri and West Virginia saw little violence but only piecemeal integration until the late 1950s and early 1960s. School boards in these states typically integrated only one or two grades each year.

The gradual elimination of legal segregation did not remove barriers to meaningful integration. Black students were often barred or heavily discouraged from participating in extracurricular activities they had previously enjoyed. More importantly, the end of segregation also meant that many black teachers were fired rather than permitted to teach in mixed-race schools. Black communities lost control of venerable institutions such as Sumner High in St. Louis and Garnett High in Charleston, West Virginia. These schools were the center of black community life and boasted a teaching corps with more advanced degrees than many colleges. Integration was recognized as an important step toward racial equality, yet for black students who navigated a gauntlet of racism each morning, black teachers who lost their jobs, and black community members who lost control of their local schools, integration continued to place the burden of race squarely on their shoulders.

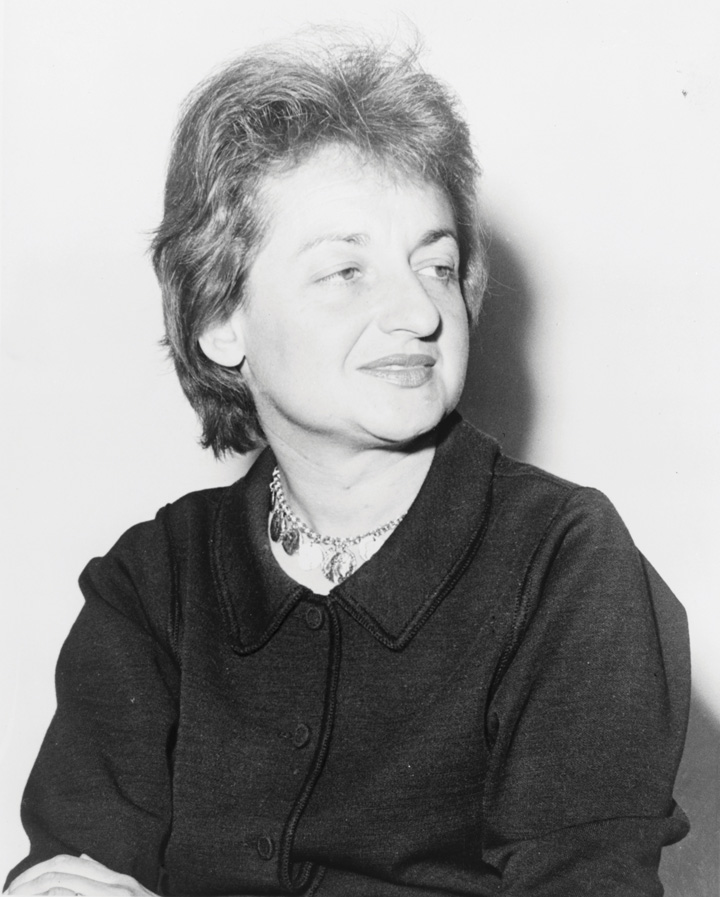

Figure 11.6

Betty Friedan was a labor activist and the author of the influential book The Feminine Mystique. She would also become the founder and first president of the National Organization for Women (NOW).

Even as more and more Americans supported the idea that race should not be a barrier to employment, most Americans believed that gender was a valid consideration on the job market. Newspapers divided their advertisements for jobs into “Help Wanted (Male)” and “Help Wanted (Female)” sections, and most large businesses kept separate lists of male and female employees for purposes of determining seniority and promotion. Given the assumption that women were provided for by a male breadwinner, few companies provided benefits such as health insurance or pensions for female employees. For those female workers who were married to husbands who received family benefits, these kinds of benefits were less important than fair pay. But for the 40 percent of working women who were single, and for the women who might someday become divorced or widowed, gendered assumptions about wages and benefits were painful reminders that they were not part of the idealized female world of pampered domesticity.

At the same time, many women believed that gender differences should be considered in the workforce. Many states had laws granting time off for pregnancy and child care and other provisions specifically designed to protect women in the workplace. Some of these laws, such as limitations on the number of hours a woman might be required to work, might either benefit a particular female employee or serve as a barrier from obtaining needed overtime pay. In addition, some companies had internal policies granting women longer breaks, days off for child care, and even more days for sick leave. Some women worried about whether laws mandating an end to gender discrimination might lead to the elimination of laws protecting pregnant workers or recognizing the domestic responsibilities of women who worked part time.

The emerging civil rights movement and the experience of many women in labor unions helped to promote ideas about the rights of the individual and the power of collective action. Even as the nation’s imagined “ideal woman” took a step away from “Rosie the Riveter” and toward the popularized image of sitcom housewives Donna Reed and June Cleaver, a number of female activists mobilized in favor of greater opportunities for women who worked outside of the home by choice or necessity.

One of the greatest obstacles these women had to overcome was the notion that female employment outside the home was unnatural or undesirable. Many women, as well as men, viewed female labor as a temporary evil that should only be endured during periods of personal financial crisis or war. Many activists tried to show the nation that the idealized image of a dependent housewife within a well-provisioned home not only limited women’s freedoms but also ignored the reality of life for many women. Nearly half of working women at this time were single, and 10 percent of children were born out of wedlock throughout the 1950s and 1960s. Others tried a more radical approach using the rhetoric of labor unions about the rights and dignity of all workers combined with the tactics of civil rights activists.

Similar to feminists of previous generations, women’s rights activists used both conservative and radical approaches to spread their message. For example, one popular conservative strategy was to liken opponents of equal employment as cowardly assailants of women and mothers, many of whom lacked “male protection.” Others sought to connect women’s patriotic service against fascism in World War II with the ongoing contest against Communism. Others like Betty FriedanAn author for several labor organizations, Friedan challenged the practices of US corporations in paying women less than men for the same work. Friedan is most famous as a writer for her book The Feminine Mystique, which challenged Americans to reconsider the notion that women were naturally content living a life of domesticity. Friedan would later found the National Organization of Women and become its first president. became involved in labor unions and exposed corporate wage tables that used gender as a determinative factor. For example, one of Friedan’s articles listed the pay rates for male and female laborers in leading companies like General Electric and Westinghouse. The same article revealed that the average black woman earned less than half of the average white woman and that the pay differential between men and women resulted in billions in corporate profits.

Friedan rose to prominence after publishing The Feminine Mystique, a book capturing the discontent that many American women felt in a society that minimized their contributions and restricted their options. She and other women of the postwar period helped to create what soon became known as Second Wave FeminismA blanket term for the growth of women’s rights activism in the late 1950s and 1960s, Second Wave Feminism refers to attempts to eliminate social and economic discrimination against women. The First Wave refers to those who fought for the elimination of legal barriers, such as the rights of women to vote, hold private property, and run for political office. Members of the Second Wave argued that the elimination of legal barriers had not removed all forms of discrimination against women. Although commonly associated with the 1960s and 1970s, the roots of Second Wave Feminism can be seen in the postwar era.. By this definition, previous generations of feminists were part of a First Wave that worked to overturn legal obstacles to equality, such as prohibitions against women’s suffrage and property ownership. Women of the postwar period were part of a Second Wave that challenged lasting inequalities, which remained impervious to the repeal of explicitly discriminatory laws. In so doing, these 1960s feminists sought to establish and defend equal rights and opportunities for women. In an era where most women accepted a modified version of the “separate sphere,” feminists of the 1960s challenged the notion that gender should predetermine one’s role in society.

Most women in the 1960s took a more tactical approach, seeking tangible gains for women in the workforce, including safeguards against termination for life events such as marriage and childbirth. This was important, because employers at this time frequently dismissed female employees when their pregnancies became known. These mothers were generally replaced by younger women who could be paid less and would agree to contracts stipulating that they would resign if they should become pregnant. This practice not only thwarted a woman’s ability to achieve seniority and promotion but also reinforced notions that female employment was temporary. Few companies would bother training even the most talented young women for positions beyond the entry level if they believed their ability to serve the company would be interrupted for two or three decades following childbirth and motherhood.

Dozens of industrial nations had provisions guaranteeing time off and some financial compensation for pregnant employees by 1950. In the United States, only Rhode Island had a similar provision at the state level, and it would take nearly three decades for the federal government to pass similar legislation. Women’s leaders and organizations in the United States participated in the United Nations International Labor Organization, which, among other things, sought to define and defend the rights of female workers. In 1952, this organization recommended that employers be required to provide medical coverage and twelve weeks of paid leave for pregnant women. Most Americans paid little attention to these recommendations and believed that companies should not be required to provide even unpaid leaves of absence. Even the more radical American women who participated in the 1952 meetings believed that the UN recommendation would result in fewer companies being willing to hire women of child-bearing age. As a result, women’s groups in the United States lobbied for provisions guaranteeing that pregnant women could keep their jobs and take unpaid leaves of absence. With the exception of state and local laws, their efforts were not rewarded until the Pregnancy Discrimination Act of 1978.

Popular culture soon reflected the movement from the city to the suburbs. Leading sitcom families in 1950s programs such as I Love Lucy and The Honeymooners were apartment dwellers, but by the 1960s, Americans gathered to watch the daily lives of suburban families in Leave it to Beaver and similar programs. While popular culture extolled the virtues of suburban life, a new generation of restless suburban youths continued to embrace counterculture modes of expression. Beneath the façade of conformity and contentedness, the youths of the early 1960s experimented with similar styles of music, literature, and drugs the beatniks had embraced in the previous decade.

Although few beatniks would have appreciated the tribute, 1960 was also the year that a British rock band called themselves The Beatles and began their meteoric rise. Offering a middle-class version of the rebellious posturing of the previous generation, The Beatles soon embodied the essence of suburban youth culture in the mid-1960s. The final years of the decade, however, featured a culture far more rebellious than the clean-cut teen idols from Liverpool. In 1969, half a million hipsters and fellow travelers converged upon a farm in upstate New York in 1969 to witness rock ‘n’ roll deliver its own proclamation of emancipation at a concert called Woodstock.

Lyndon Johnson rose to prominence in 1948 after election returns of questionable veracity declared the young man from the hill country of Texas that state’s senator by a mere eighty-seven contested votes. Now president, Johnson hoped to put the unfriendly nickname of “Landslide Lyndon” behind him forever by becoming the next Franklin Roosevelt. Although the economy appeared strong, sociologists had produced numerous studies detailing how a fifth of the population lived in squalor. Johnson’s supporters believed that the persistence of poverty in the wealthiest nation on the globe was more than a cruel paradox. In response, one of the first initiatives Johnson declared was a “war on poverty.” In August 1964, Congress passed Johnson’s Economic Opportunity Act. This law provided an average of $1 million for nearly 1,000 locally organized community action agencies around the nation. The president also created the Job Corps, which provided vocational training for young adults in the hopes of breaking the cycle of poverty.

Johnson labeled his sweeping domestic agenda as The Great SocietyThe slogan used by President Lyndon Johnson to promote a variety of proposed domestic legislation aimed at eradicating poverty and racial injustice. and proposed dozens of new laws and new agencies to deal with the problems of poverty and racial injustice. Supporters hailed the programs launched between 1965 and 1967 as a modern-day New Deal complete with a new alphabet soup of federal programs. The Volunteers in Service to America (VISTA) employed young and old Americans to conduct service projects in impoverished cities. Two new cabinet-level agencies, the Department of Transportation (DOT) and the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), were added to the alphabet soup of federal acronyms. Johnson also supported the creation of the National Endowment for the Humanities and the National Endowment for the Arts, provided federal assistance for public broadcasting, and increased federal aid for colleges and students. The most controversial programs, however, were those that provided direct payments to the poor. Food stamps and other programs shifted the burden of poverty relief from cities and states to the federal government. Although some feared that Johnson’s welfare programs would encourage dependency and sap the ambitions of the poor, many greeted the program with optimism, believing that it would reduce fraud while providing a more complete security net against poverty.

Figure 11.7

This 1968 poster was made by the federal government to inform seniors about Medicare, a program that was part of the Social Security Act of 1965. Medicare is a federal health insurance plan that provides benefits for individuals who are eligible for Social Security.

This optimism was not enough to carry an ambitious plan to provide national health insurance, a plan originally proposed by FDR that continued to stall in Congress throughout the 1960s. Congress and President Johnson instead secured passage of MedicareA leading provision of the 1965 Social Security Act, Medicare provides health insurance for Americans age sixty-five and older who meet other eligibility requirements for Social Security benefits. in 1965, a federal system of health insurance for the elderly. Less than half of Americans above the age of sixty-five had any medical insurance, a situation that prevented many older Americans from obtaining medical care. Given the political power of senior citizens, the president quickly approved Congress’s plan to fund Medicare through an increase in Social Security taxes. The original plan failed to cover dental care, eyeglasses, certain prescriptions, and a host of other important services and procedures. However, seniors could choose either Plan A, which offset most hospital bills, or Plan B, which functioned much like an employer’s health plan with the recipient paying small premiums while the government shouldered the majority of the cost. Congress also approved MedicaidCreated in 1965 as part of Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society, Medicaid is a federal program administered by states and provides health insurance to the disabled and low-income Americans who are eligible for federal assistance., a program providing medical benefits for recipients of welfare and the disabled.

Although the federal government had passed numerous laws guaranteeing the right to vote regardless of race, African Americans throughout the South continued to be disenfranchised by a variety of methods. Black leaders throughout the South challenged their exclusion. Thousands had worked quietly to increase voter registration throughout the 1940s and 1950s, yet fewer than 2 percent of eligible black voters were registered and even fewer were able to vote. For example, black and white leaders at the Highlander Folk School in the Appalachian Mountains of Tennessee launched citizenship education schools throughout the South. Under the leadership of civil rights veteran Septima ClarkKnown to many as “Freedom’s Teacher,” Clark innovated the use of citizenship education schools that taught black Americans reading skills that prepared them to pass literacy tests required for voter registration. As director of the Highlander Folk School’s outreach program, she trained and recruited teachers of these schools throughout Appalachia and the South. and teachers like South Carolina’s Bernice Robinson (a beautician with no teaching experience), these schools taught literacy skills needed to pass voter registration exams. Robinson’s role as a beautician was important because she was self-employed and her clients were all black. Unlike existing public school teachers, Robinson could not be fired by a white school board member or harassed by a white suprervisor as had occurred so often in the past.

The citizenship school movement expanded rapidly in the early 1960s. Leaders from a variety of civil rights organizations, such as CORE, along with hundreds of Northern college students descended upon Mississippi in 1964 in what became known as the Mississippi Freedom SummerA sustained campaign by local African Americans and college students throughout the nation to protest continued disenfranchisement in Mississippi and throughout the South. Students taught reading skills to adults wishing to pass literacy tests while local activists formed their own political party to protest their exclusion from the white-controlled Democratic Party of Mississippi.. Many of the rural counties in the Delta had black majorities yet did not have a single registered black voter. Whites claimed that this was because black residents cared little for politics, but the reality was that any black person who registered to vote did so at great personal risk. For example, in 1963 Mississippi passed a law requiring the name of any new registrant to be published in the city paper. Allegedly meant to provide fellow citizens an opportunity to identify any nonresident, felon, or otherwise nonqualified voter, any black residents whose names were published soon found themselves fired from their jobs, evicted from their homes, and a handful even went missing.

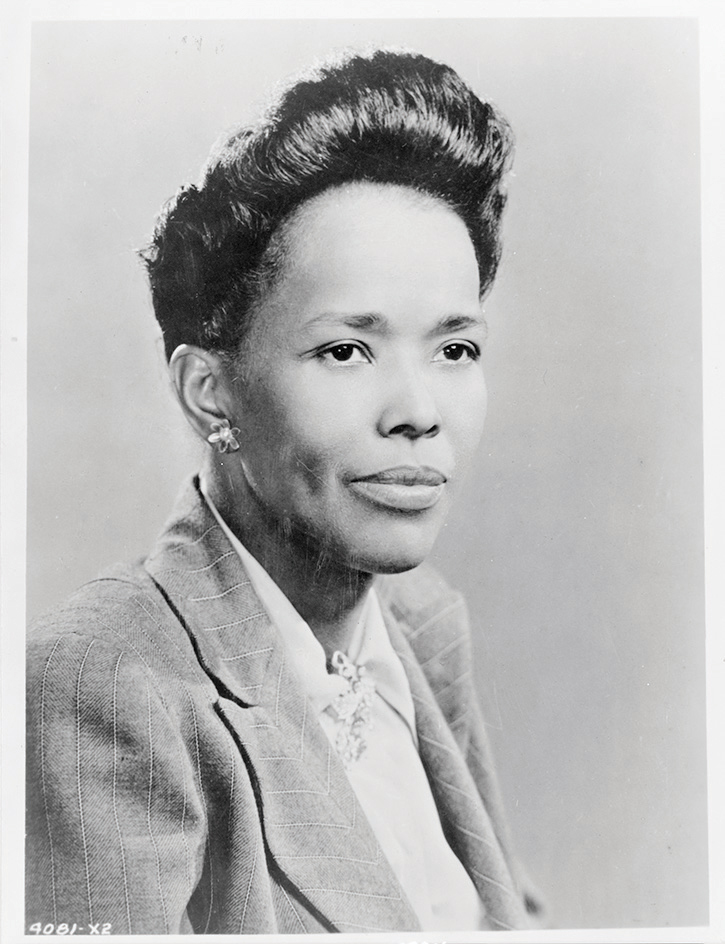

Figure 11.8

Civil rights leaders Septima Clark (left) and Rosa Parks (right) enjoy a moment together at the Highlander Folk School in Monteagle, Tennessee.

Mississippi law also required any potential registrant to read and interpret a section of the state constitution. A provision officially meant to screen against illiterate voters who might accidentally vote for the wrong party, the test was often used to reject black voters. The exam was a subjective measure administered by white registrars who often failed black attorneys and black professors while approving the applications of illiterate whites. In George County, one white applicant interpreted the phrase “There shall be no imprisonment for debt” to mean “I thank that a Neorger should have two years in collage before voting because he don’t under stand.” This individual, and tens of thousands of other semiliterate whites, passed the exam. In other areas, however, the laws were used to restrict poor whites with little opportunity for education from voting. As a result, some poor whites joined the Freedom School movement and recognized their common cause with black Southerners.

The Freedom Summer challenged the nearly complete disenfranchisement of African Americans in the Deep South as thousands of black and white college students from throughout the nation converged upon Mississippi and other states to register black voters. Following the methods of Septima Clark’s citizenship schools, participants in the Freedom Summer organized classes that prepared potential voters for the registration exam. Robert Moses, a former school teacher who had been working in the state to register voters, helped to train the students and prepare them for the threats and violence they would face. Almost a thousand attended a week-long workshop at Miami University in Ohio where they learned skills such as how to protect their head and vital organs while being clubbed.

We knew, we knew that to get black people registered to vote…but we also knew that for many of those people who weren’t registered, the most important thing to them was often something different. Causing political change through voting was too intangible at first. They wanted to be able to order something out of a catalog, or read a letter from one of their children from out of town without having to take it to a neighbor or their white employer. That meant more to them than a registration certificate at that moment. They just couldn’t see that far down the road. So you dealt with them on that level. You had to. The rest followed. That’s why those schools worked.

—Bernice Robinson, Highlander Participant and Citizenship School Teacher in Coastal South Carolina

This training proved invaluable as the students dedicated themselves to nonviolent resistance. Hundreds were attacked and arrested, while dozens of churches that were used to hold classes were bombed. Three civil rights workers, James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner, went missing while traveling through Philadelphia, Mississippi, that August. Hundreds of reporters and FBI investigators swarmed Mississippi to join in what many increasingly realized was a recovery operation to find the bodies of the three young men. “We all knew that this search with hundreds of searchers is because Andrew Goodman and my husband are white,” Rita Schwerner explained to a shocked nation. “If only Chaney was involved, nothing would have been done.” Investigators stumbled upon a half-dozen bodies of local black civil rights workers before finding the three students.

Figure 11.9

Fannie Lou Hamer was one of the sharecroppers who registered to vote during the Freedom Summer of 1964. She was fired, evicted, arrested, and beaten while in prison for her efforts to register other black voters. She is pictured here representing the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party at the 1964 Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City, New Jersey.

The funeral of James Chaney reflected the anger of many African Americans as they increasingly recognized the second-class status they were given in their own freedom struggle as TV cameras and FBI investigators continued to only report on the actions of white students. But the civil rights movement did not yet fragment along racial lines as it would in the late 1960s. The presence of white students brought TV cameras, which publicized the plight of Southern blacks who recognized that the students were one of the few allies they had. Together, some progress was made even in places like Leflore County where no African Americans had voted in years. A county with a black majority, 1,500 black residents attempted to register, and with the national media present, local registrars could find no reason to disallow 300 of these applications.

Whites in Mississippi prohibited black voters from participating in the Democratic primaries, claiming that this was legal because their organization was private and therefore exempt from the Fifteenth Amendment. African Americans and a handful of white supporters formed the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) in response. The MFDP challenged the legitimacy of the white-only Mississippi delegation to the 1964 Democratic National Convention. Wishing to keep white Southern voters from supporting a third-party segregationist candidate, the Democratic Party recognized the white-only Mississippi delegation and offered the MFDP only a token number of delegates. MFDP leader Fannie Lou Hamer soon became the public face of the voting rights movement in Mississippi when she explained why her organization could not accept this token offer. Hamer described her own experience of being beaten while in prison for attempting to register black voters in Mississippi, exposing the hypocrisy of Democratic leaders who spoke of the political sacrifices they had made by offering token support to the MFDP. The following year, Democrats hoped to avoid future controversy and approved the 1965 Voting Rights ActA law intended to enforce the provisions and intent of the Fifteenth Amendment, which barred race as a reason for denying any US citizen the right to vote. The law gave the federal government the power to oversee elections and intervene if it believed that the rights of voters were being infringed.. This law allowed for federal supervision of voter registration and elections when racial discrimination was suspected. “Mississippi has been called ‘The Closed Society,’” explained organizer Robert Moses. “We think the key is in the vote.”

President Johnson praised education as the “key which can unlock the door to the Great Society.” The president supported the Higher Education Act, which expanded work-study programs and provided loans for tuition and living expenses. These loans would be serviced through private banks but would feature low interest rates because the federal government would guarantee payment. Now all young adults who did not have a wealthy family member to cosign their college loans could turn to their Uncle Sam.

More controversial was Johnson’s desire to vastly expand federal aid to K-12 education. Kennedy had attempted a similar measure, but his opposition to funding parochial schools (a provision the Catholic Kennedy supported but feared would prove politically suicidal) derailed the measure. Johnson’s bill worked around the controversy by providing subsidies for families with children in private schools (rather than the schools themselves). The primary feature of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, however, was the allocation of $1 billion in federal aid for public schools. By bridging the political divide between the supporters of private and public schools, Johnson’s bill was the first legislation providing significant funding to K-12 education. Previous laws tied this funding to school integration, which probably did more than Brown v. Board to encourage integration in hundreds of school districts. Equally important, the 1965 law began a historic shift in the way public schools were financed. Advocates of federal aid believed that this revenue would compensate for the inequities of locally funded schools. However, poor districts still spent far less per pupil, and federal aid increasingly became an excuse to cut school funding in many districts.

Medicare provided benefits for nearly 20 million Americans but did not cover a host of expenses, such as prescription drugs, leading many to criticize the program for its “gaps” in coverage. In addition, the program quickly became one of the government’s leading expenses and required continual increases in taxes. Part of the reason was that the plan was designed to placate lobbyists representing the American Medical Association (AMA), which had derailed two decades of government health insurance proposals that contained cost controls and limits on procedures as “socialized medicine.”

Desirous to pass the law without the opposition of the AMA, the plan did little to regulate the costs of medical care or the procedures that might be covered. As a result, medical providers were now paid primarily by insurance companies and the federal government, and they responded by raising their prices an estimated 14 percent per year. Unlike the free market where consumers pay directly and therefore shop for the best prices, recipients of Medicare and Medicaid cared little for the cost of service. Medicaid recipients had previously gone without medical service due to their inability to pay, but once the federal government assumed payment for emergency care, an increasing number of poor Americans went directly to emergency rooms for medical care. In addition, a handful of doctors set up clinics in poor neighborhoods, and these clinics routinely performed unnecessary and expensive tests on Medicaid clients as a way of defrauding the government.

Figure 11.10

Claudia Taylor Johnson, better known as “Lady Bird” Johnson, celebrates a Minnesota Head Start program with some of its students. The First Lady was active on behalf of a number of causes during her husband’s administration and was also a successful business leader both before and after her tenure in the White House.

The nation’s increasing standard of living, expanded government programs for the poor, and even the rhetoric of civil rights activism were helping to create a culture of entitlement among many Americans. The notion that a certain minimum standard of living was a “right” that all Americans were entitled to increasingly gained currency throughout the 1960s. Most recipients of government aid in the United States ate meat every day and lived in homes with electricity, running water, and central heating. Each of these was a rare luxury in most nations, while the latter three were relatively new inventions. However, federal programs such as Aid to Families with Dependent Children operated through matching grants to states and therefore failed to provide any benefits to some of the poorest families in states that could not adequately subsidize the program. Still, conservative reservations about providing direct aid to the poor, combined with reported abuses of governmental assistance, led to relative declines in public support for Johnson’s war on poverty.

Figure 11.11

As a daughter of the Jim Crow South, civil rights leader Ella Baker devoted most of her efforts to challenging racism. However, Baker also believed that racism was a symptom of a larger social illness that kept people and communities from recognizing their common interests and working together to solve common problems.

One of the first casualties of the Great Society was the gradual defunding of community action agencies. Inspired by sociologists who identified a “culture of poverty” as the greatest enemy in Johnson’s war, federal money was supposed to be directed to these local and autonomous community groups who would then decide how the money would be best spent. The law required that the poor themselves were supposed to lead these groups as much as possible, a provision Johnson hoped would help the poor to learn to help themselves. The provision was both simple and radical. If larger and larger numbers of poor people became engaged in their own welfare, the cycle of poverty might slowly grind to a halt.

Believing that ordinary people who mobilized in an organized, democratic, and meaningful manner might reinvent themselves and their communities, reformers and activists joined with the working poor to create a host of programs such as Head Start, which provided aid for education in poor communities. Many liberals hoped the Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO) would radically challenge the concept of democracy. As civil rights icon and community organizer Ella Baker explained, “In order for us as poor and oppressed people to become a part of a society that is meaningful, the system under which we now exist has to be radically changed.” For Baker, this meant that the people must “learn to think in radical terms…getting down to and understanding the root cause” of their problems and “facing a system that does not lend itself to your needs and devising means by which you change that system.”

However, those that hoped the OEO might breathe new life into poor neighborhoods and new meaning into the concept of democracy were disappointed by the limited funding that represented less than 1 percent of the federal budget and less than $230 for each of the 35 million poor Americans each year. At the same time, the decentralized nature of the plan also provided ample opportunity for mistakes or even fraud. All the rhetoric about these groups providing a “hand up instead of a handout” for the poor was quickly forgotten when a handful of those hands misappropriated funds. In addition, while the president portrayed himself as a modern-day FDR, Johnson increasingly focused his efforts on events overseas. Just as Truman’s social programs were derailed by a war in Asia, efforts to contain the spread of Communism largely determined the outcome of Johnson’s presidency after 1965.

Although the United States had been actively involved in Vietnam for over two decades, Southeastern Asia was still a peripheral interest to US officials until the mid-1960s when Communist forces under Ho Chi Minh appeared ready to take over the southern portion of the country. The growing power of Communist North Vietnam and the declining position of the US-backed government of South Vietnam led many officials to assume that the North’s success was part of a Soviet and/or Chinese plot to spread Communism throughout the globe. In reality, China and the Soviet Union were antagonistic to one another and did not coordinate any substantial action regarding the situation in Vietnam. Ho Chi Minh did receive Soviet aid, but recent scholars have determined that the Soviet strategy was not based on the aggressive and expansionistic worldview US leaders feared. In fact, it appears the Soviets and Americans viewed events in Vietnam in very similar terms.

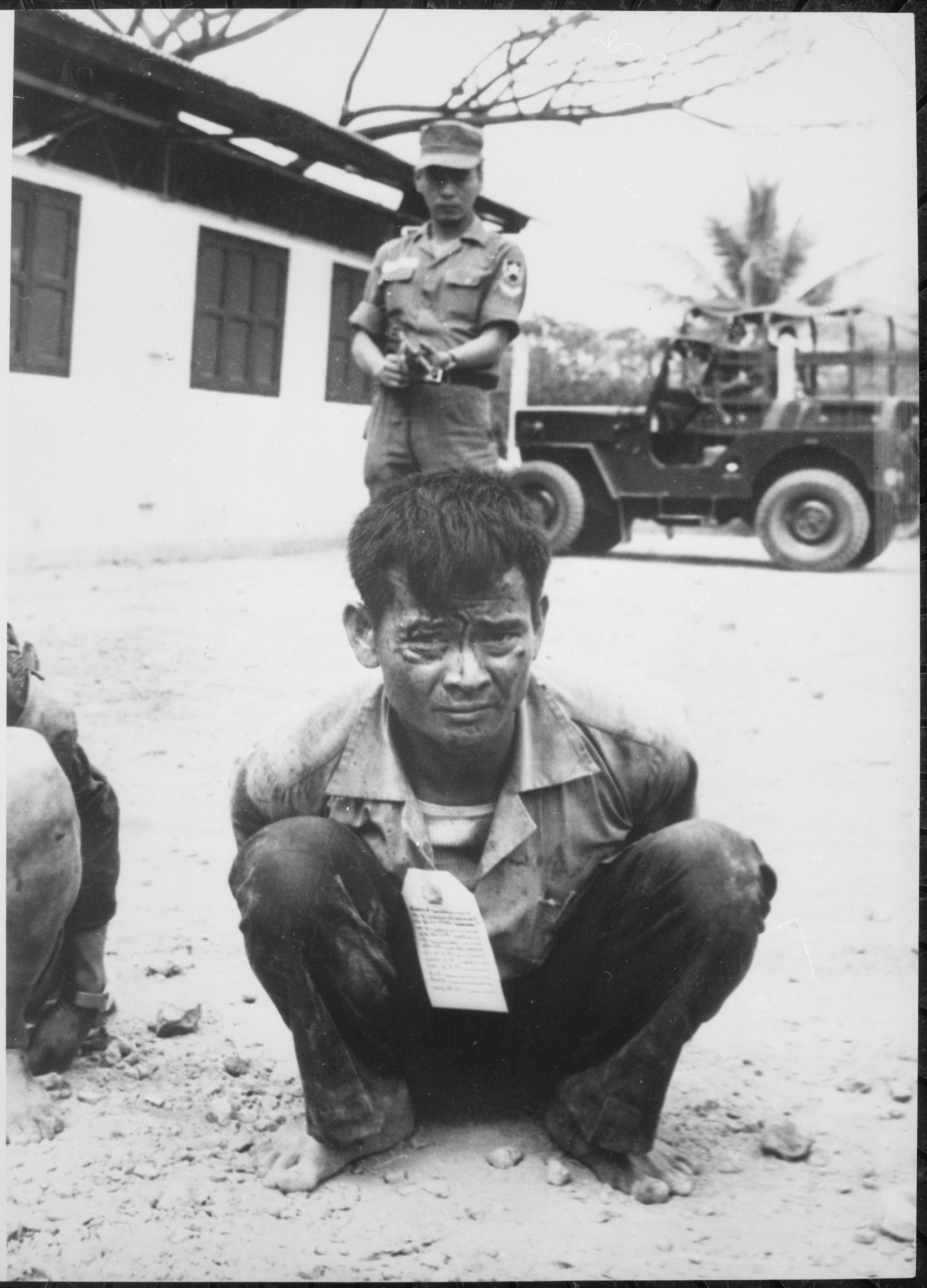

Figure 11.12

A South Vietnamese soldier guards a young boy who was believed to have participated in an attack against US and South Vietnamese forces. The Vietcong recruited women, children, and the elderly in their guerilla war against the South and the United States.

Americans shared deep reservations about supporting the non-Communist dictatorship of South Vietnam. The Soviets were equally hesitant to support the authoritarian regime led by Ho Chi Minh. Soviet leaders did not believe the North Vietnamese army or the Vietcong were true followers of Marxism and recoiled at the many human rights violations these troops committed. However, the Soviet Union had its own domino theory about what might happen if Communist governments such as Hanoi fell due to Western intervention. If they failed to support Ho Chi Minh as he battled the forces of Capitalism and imperialism, the Soviets asked, what message would this send to Communist leaders around the globe? The United States shared a similar global perspective in backing the South Vietnamese. So, fearing international consequences if they failed to act, both the United States and the Soviet Union backed regimes of which they were not enthusiastic supporters and hoped for the best. As a result, Vietnam turned from a civil war to determine the leadership of a newly independent country to a proxy war between the two superpowers neither wanted to fight.

The United States became increasingly reluctant to support the South Vietnamese after the Catholic Ngo Dinh Diem approved a series of raids against Buddhist monasteries in 1963. Diem believed that the Buddhist majority was hostile to his regime, and instead of seeking mediation, he used US military aid to his army to conduct mass arrests of Buddhist leaders. In response, the Kennedy administration conveyed the message to a handful of South Vietnamese military leaders known to share US reservations about Diem’s leadership that the United States would support a coup if it meant removing Diem. Kennedy was personally hurt to find out that the result of the coup, which occurred two months after his message was conveyed, resulted in Diem’s assassination.

The leadership of South Vietnam was transferred to the South Vietnamese military, which was equally corrupt and authoritarian. President Johnson continued to provide this government with military aid, largely due to a fear that failure to do so would lead to a North Vietnamese victory and vindicate Republican allegations that he was soft on Communism. The South used this aid to conduct raids on the North. As a result, the North viewed all South Vietnamese and US warships in the adjacent Gulf of Tonkin as enemies. When a handful of small North Vietnamese boats fired at but did not harm a US destroyer in August 1964, President Johnson requested congressional authority to respond militarily.

The actual attack on the US ship was miniscule and a second alleged attack may not have even occurred. However, Congress responded by almost unanimously approving the president’s request in what came to be known as the Gulf of Tonkin ResolutionA nearly unanimous congressional approval of Lyndon Johnson’s request to use his authority as commander in chief to escalate military operations in Vietnam. The Resolution was passed after limited debate following a series of reported attacks on US warships in the Gulf of Tonkin.. The American public was understandably outraged to hear of the “unprovoked” attacks on US servicemen in the Gulf and supported Congress’s decision to grant Johnson’s sweeping power “to repel (future) attacks…and prevent further aggression.”

The public was never made aware that the destroyer in question was involved in an operation against the North Vietnamese. They were also not informed that South Vietnamese forces were launching nightly raids against the North using vessels given to them by the United States. Nor did the public believe that the resolution would later become the basis by which two US presidents would wage a war without a specific congressional declaration. The public did generally approve, however, of President Johnson’s immediate actions following congressional approval of the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution. To show US resolve against the perceived threat of Communism in North Vietnam, the president approved aerial attacks against military targets and sent tens of thousands of troops to bases throughout the region.

The United States sent more than 150,000 troops by the end of 1965. Each of these soldiers soon shared complaints about the ineffectiveness of the South Vietnamese army they were sent to support. Consisting of mostly conscripted South Vietnamese troops who had little faith in their own government, the leading priority of these young men was to stay alive rather than confront communists. Even when given superior weapons and support, the South Vietnamese soldiers often dropped their weapons and ran when they confronted the Vietcong. US soldiers soon dubbed these South Vietnamese misadventures “search and evade” missions rather than the official moniker which was “search and destroy.”

The Vietcong, in contrast, made up for its lack of equipment with a much stronger resolve to fight. US soldiers soon developed a grudging respect for these “VCs” as they were called. Many of the VC leaders were veterans of the long fight for independence from France and Japan. This core group of an estimated 60,000 guerilla warriors was augmented by 100,000 to 200,000 more civilians who exchanged plowshares for rifles throughout the year and then returned to peasant farming. Known by dozens of inhuman epithets, the Vietcong soon became known by a more human moniker as soldiers using the military alphabet referred to “VC” as “Victor Charlie” and eventually just “Charlie.”

The Vietcong and North Vietnamese were generally very familiar with the local terrain, placed thousands of deadly traps throughout the jungle, and utilized hit-and-run guerilla warfare against the US and South Vietnamese troops. They also disguised themselves as local villagers and forced many civilians to join them. Even women and children regularly carried weapons and used them against US and South Vietnamese forces. As a result it was nearly impossible to distinguish between civilians and soldiers in a war where villages became part of the battlefield.

General William WestmorelandUS Army general and commander of US forces in Vietnam between 1964 and 1968. Westmoreland’s strategy was based on his belief that the United States must escalate the war and overwhelm the North Vietnamese and Vietcong through superior firepower and resolve. He believed that the United States was wearing down the enemy and regularly provided exaggerated numbers of enemy killed in battle and underestimated the continued strength of the VC in ways that led many to question his leadership following the Tet Offensive. recognized all of these challenges, yet believed that more troops, more bombing raids, and more supplies would eventually wear down the enemy. After all, he believed, the United States enjoyed superior technology and possessed immense resources the North Vietnamese army (NVA) could not compete against. Even Ho Chi Minh agreed with this assessment of superior US material resources, but believed that the ideological commitment of his supporters would mitigate the difference. “You can kill ten of our men for every one we kill of yours,” Ho allegedly communicated to a French adversary in the 1940s. “But even at those odds, you will lose and we will win.”

While it should be mentioned that authenticity of the previous quote cannot be verified, the statement accurately reflects the way both US and Communist forces fought throughout the Vietnam War. General Westmoreland and other US officials focused on exterminating the NVA and VC rather than the more conventional military strategy of taking and holding ground. The NVA and VC, on the other hand, recognized that they would seldom inflict more casualties on the enemy given their disadvantages. They often demonstrated a fatalistic resolve to continue the war, despite heavy losses. Part of this devotion was ideological and reflected an individual’s conviction that Ho Chi Minh was leading his nation in a fight for independence from outside influence. At the same time, the VC and NVA used extreme coercion against those who opposed them, including their own recruits. VC and NVA who refused orders, or even civilian villagers who cooperated with the United States and South Vietnamese were often executed.

Hoping to demonstrate US resolve and firepower, as well as convince the South Vietnamese that they could defeat the North with US assistance, Johnson ordered a sustained bombing campaign in March 1965. Known as Operation Rolling ThunderA sustained bombing campaign that dropped more ordnance on targets throughout Vietnam between 1965 and 1968 than was delivered by all belligerents through the entire course of World War II., the bombing lasted until the fall of 1968. The damage to the North Vietnamese countryside was supposed to be limited to military targets, yet it was difficult to prevent civilian casualties in a nation where the line between civilians and military was impossible to determine from the air. Most historians charge the US military with willful indifference regarding the issue of civilian casualties during Operation Rolling Thunder.

Figure 11.13

A massive B-66 bomber accompanies four F-105s in a July 1966 mission during Operation Rolling Thunder. The F-105 was a fighter jet that could also drop 14,000 pounds of explosives.

In many respects, US planners made little effort to draw this distinction between civilians and combatants in most of the wars of the twentieth century. Much like the bombing campaigns of the later years of World War II, cities were targeted in a failed effort to crush the will of the North Vietnamese military leaders. Large areas of South Vietnam were also targeted. The US military declared certain areas believed to harbor NVA and VC troops “free fire zones” and used every nonatomic weapon in its arsenal to destroy every living thing in those zones. By the end of the war, 14 billion pounds of explosives had been dropped on Vietnam, roughly 500 pounds of explosives per man, woman, and child. These bombing raids failed in their objective to end North Vietnam’s ability to launch attacks on the South. They also failed to win support for the already unpopular South Vietnamese government among the people of Vietnam.

One of the leading reasons for America’s aerial strategy was that President Johnson recognized that a land-based offensive against North Vietnam would result in tremendous US casualties. And so the bombing campaigns continued through 1968, and then escalated under President Nixon. Military leaders promised that each new bombing campaign would either convince Hanoi to end its attacks or limit the power of the North. The bombing of cities and villages had historically proven to be an ineffective method of waging war. The only exception to this rule—the use of nuclear weapons—was discussed and rejected by military and civilian leaders throughout the United States. Instead, US commanders hoped that their strategy of combined arms—aerial bombardment and traditional ground forces—would eventually wear down the VC and NVA.

By 1967, Westmoreland commanded half a million troops in Vietnam. The VC and NVA, however, used Fabian tactics of avoiding pitched battles they knew they could not win in a similar effort to wear down their enemy. US commanders responded by waging war on the countryside that was supplying the enemy. The military used napalm, an extremely flammable agent, as well as the chemical defoliant Agent Orange to destroy the 10 million square miles of jungle that provided cover for the VC. The devastation on the ecosystem was tremendous, and agents were also used directly against the fields that both the civilian population and the VC depended upon for food. This destroyed the local economy, a calculated measure that the United States hoped would eliminate the possibility of VC and NVA troops raiding local food supplies.

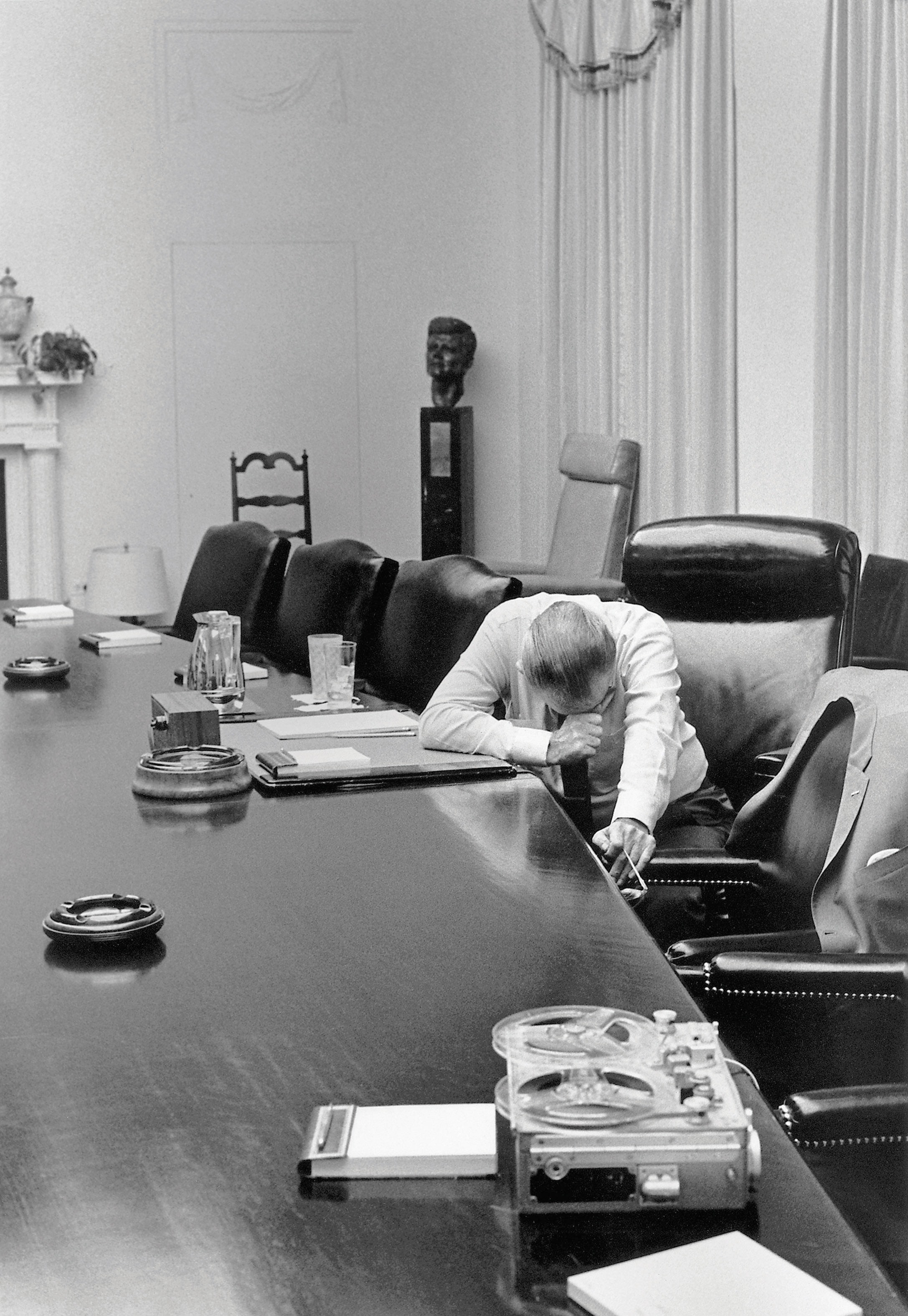

Figure 11.14

President Johnson reacts emotionally to a tape sent to him by his son-in-law, a captain and a commander of a company of US Marines in Vietnam.

Recognizing that napalm and Agent Orange would also eliminate the ability of peasants to grow crops and likely drive many to support Communist North Vietnam, the United States also provided humanitarian aid meant to guarantee the loyalty of villagers. US commanders even considered the possibility of destroying dams and flooding the entire countryside as a means of holding the entire nation hostage and forcing North Vietnamese leaders to end the war on US terms. However, these more bellicose military leaders were overruled, and the United States continued its “limited” campaigns against the North and the free fire zones of the South. The war on the countryside proved ineffective, and humanitarian aid was just as easily smuggled to or captured by the VC as the food that had previously been grown by the peasant majority. In addition, the 3 million Vietnamese in refugee camps recognized the cause of their dependency on US aid and were even more likely to sympathize with the North.

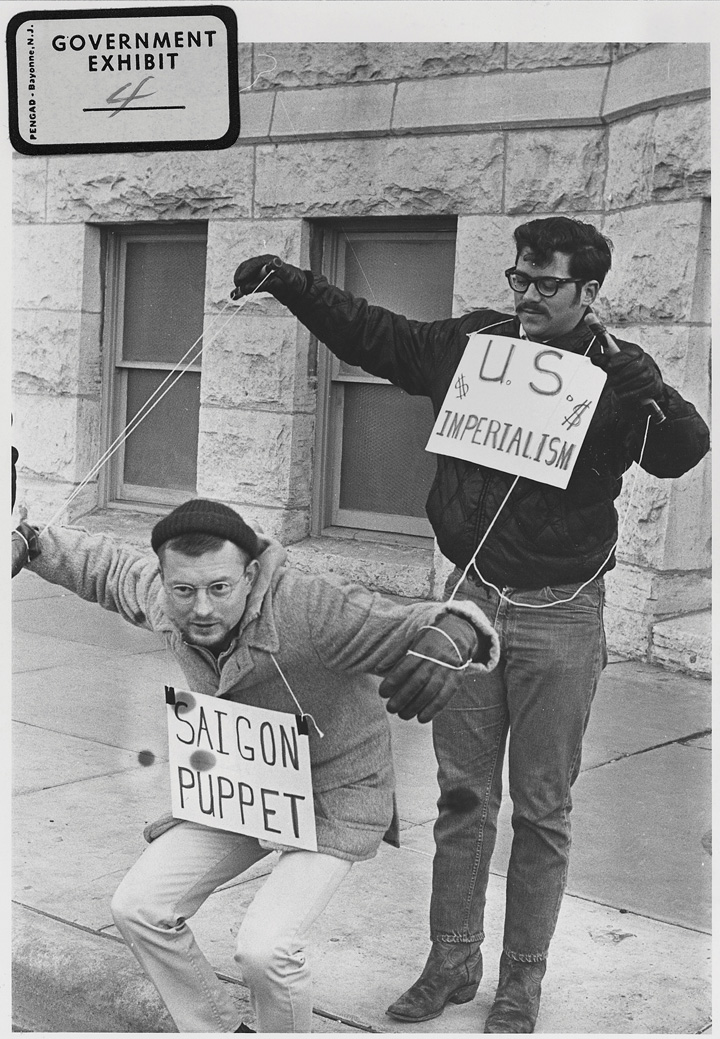

By 1967, the nation was beginning to divide on the question of Vietnam. Antiwar protests attracted only a few hundred supporters throughout 1965, but by 1967, those who opposed the war had created a movement and tens of thousands were attending protests. Most Americans still supported the war effort and viewed these protests as unpatriotic and disrespectful to the US soldiers. Many of these individuals believed that the only logical and honorable solution was to increase troop strength and intensify bombing until North Vietnam was forced to surrender.

Some protesters responded by modifying their message to emphasize their desire to support the troops by bringing them home. Others took the offensive by challenging those who favored escalation to explain how more bombing might lead to surrender and asking exactly to whom they thought the North might surrender. After all, they reminded their opponents, the United States had still not declared war and the South Vietnamese government was viewed by most Vietnamese as illegitimate. Martin Luther King increasingly came to oppose the war as the only consistent position for an advocate of nonviolence. He also feared the war diverted resources that might have been used to aggressively fund antipoverty programs. By the final year of his life, King declared that The Great Society was “shot down on the battlefields of Vietnam.”

In the years following World War II, nearly 5 million African Americans and nearly as many whites migrated from the primarily rural South to Northern cities in search of greater economic opportunity. As was true of previous migration to the North, these families were influenced by both “push” and “pull” factors. The push factors—considerations that induced Southerners to leave the South—included racial segregation for black families and scarce funding for public schools for both whites and blacks. Perhaps more importantly, the invention of a mechanical cotton picker in 1944 had resulted in larger and larger numbers of both white and black sharecroppers being evicted each year from plantations they had lived and worked on for years. The pull factors—those things that attracted migrants to the North—included higher wages, better schools, and for African Americans the absence of legally enforced segregation. In fact, many Northern states had passed laws outlawing racial segregation in schools and public accommodations.

As had been the case with the Great Migration of the 1910s and 1920s, Southern blacks found most housing closed to them. Millions of Southern white sharecroppers likewise found few options they could afford. The government began constructing public housing projects, intending to both relieve overcrowding and provide affordable housing. Yet these projects faced a number of obstacles that limited their effectiveness. The private housing industry recognized that government-subsidized housing would reduce overall demand as many potential homeowners would choose federally subsidized apartments. As a result, people representing the housing industry secured regulations making public housing only eligible for the lowest-income families, meaning that housing projects were occupied exclusively by the urban poor. This stigma led middle-class and suburban neighborhoods to oppose the construction of housing projects in their neighborhoods as harbingers of crime and other urban problems. As a result, public housing was built only in existing poor neighborhoods and concentrated poverty in inner cities.

The increase in minority and poor migration to the city intensified existing patterns of migration out of the city by white and middle-class residents. This phenomenon was labeled “white flightA term used to describe the tendency of white residents to abandon a neighborhood as soon as minority families begin to purchase homes in that area.” and altered more than the racial composition of America’s cities. When the more affluent abandoned the city, the total tax revenue that was previously available to finance the operation of America’s largest cities rapidly declined. Suburban governments and school systems were suddenly flush with cash and able to attract new employers to the periphery of the city, further depressing the city core. Suburbanization also hid the problems of the urban and rural poor by insulating residents of affluent suburbs from the decaying schools, unemployment, crime, substance abuse, and other problems that were more prevalent in poverty-stricken areas.

Housing shortages, white flight, and ghettoization were especially felt within the cities of the Midwest and East Coast. The issue affected dozens of minorities, from African Americans and Mexican Americans to new arrivals from Asia and Latin America. For nonwhites of all shades, the North reflected author Gordon Parks’s poignant description of his hometown, “where freedom loosed one hand, while custom restrained the other.” Parks grew up on a farm near Fort Scott, Kansas, very near the spot where the a black regiment fought Confederates even though the Union had not yet accepted black men in the military. Consistent with the observations of Alexis de Tocqueville long before the Civil War, Parks’s 1963 autobiographical novel The Learning Tree revealed that racial prejudice was often strongest in the places that had rejected slavery.