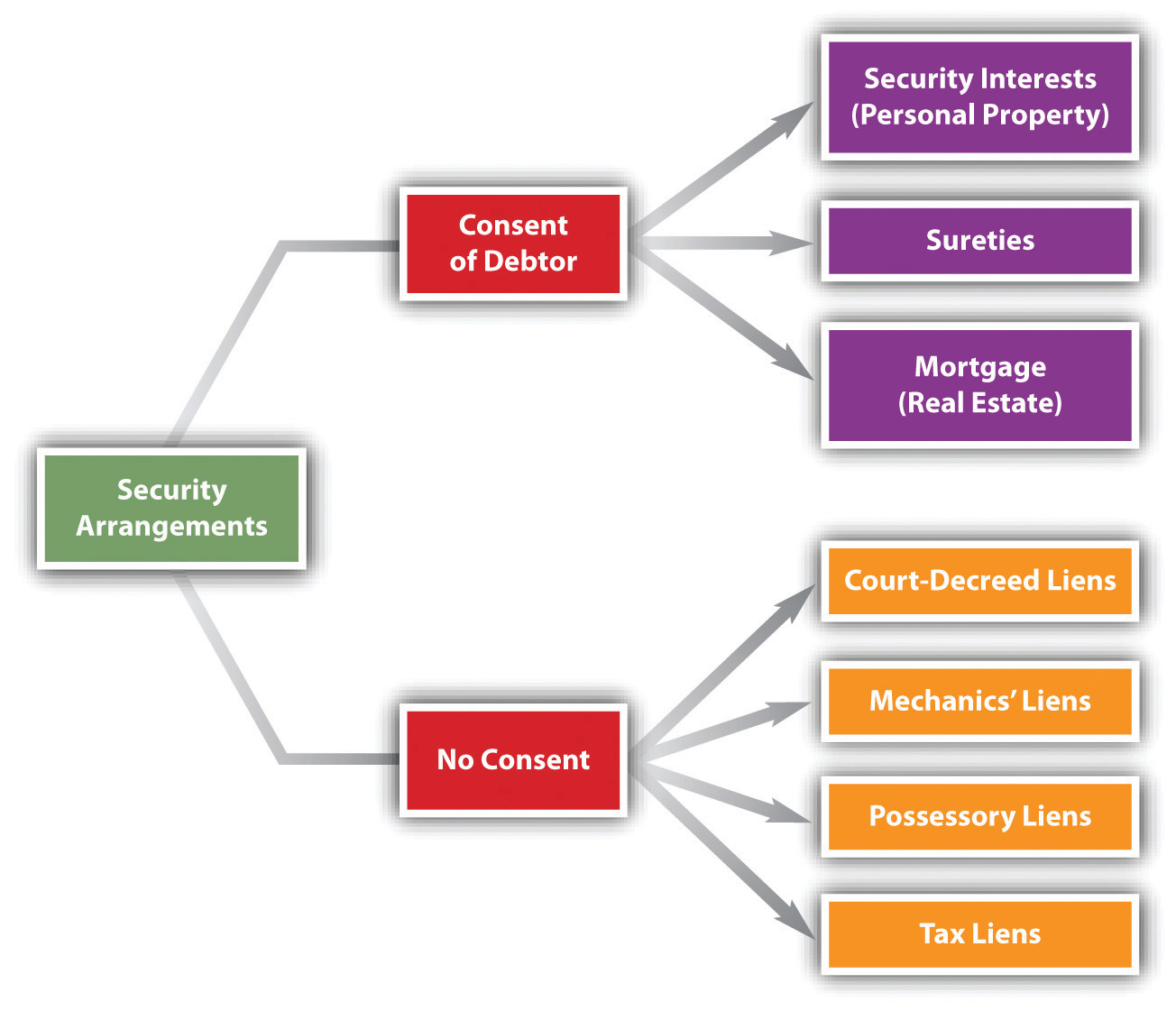

Having discussed in Chapter 19 "Secured Transactions and Suretyship" security interests in personal property and suretyship—two of the three common types of consensual security arrangements—we turn now to the third type of consensual security arrangement, the mortgage. We also discuss briefly various forms of nonconsensual liens (see Figure 20.1 "Security Arrangements").

Figure 20.1 Security Arrangements

A mortgageSecurity in which collateral is land. is a means of securing a debt with real estate. A long time ago, the mortgage was considered an actual transfer of title, to become void if the debt was paid off. The modern view, held in most states, is that the mortgage is but a lien, giving the holder, in the event of default, the right to sell the property and repay the debt from the proceeds. The person giving the mortgage is the mortgagorOne who gives a mortgage; the debtor., or borrower. In the typical home purchase, that’s the buyer. The buyer needs to borrow to finance the purchase; in exchange for the money with which to pay the seller, the buyer “takes out a mortgage” with, say, a bank. The lender is the mortgageeThe party who holds a mortgage; the creditor (such as a bank)., the person or institution holding the mortgage, with the right to foreclose on the property if the debt is not timely paid. Although the law of real estate mortgages is different from the set of rules in Article 9 of the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) that we examined in Chapter 19 "Secured Transactions and Suretyship", the circumstances are the same, except that the security is real estate rather than personal property (secured transactions) or the promise of another (suretyship).

Most frequently, we think of a mortgage as a device to fund a real estate purchase: for a homeowner to buy her house, or for a commercial entity to buy real estate (e.g., an office building), or for a person to purchase farmland. But the value in real estate can be mortgaged for almost any purpose (a home equity loan): a person can take out a mortgage on land to fund a vacation. Indeed, during the period leading up to the recession in 2007–08, a lot of people borrowed money on their houses to buy things: boats, new cars, furniture, and so on. Unfortunately, it turned out that some of the real estate used as collateral was overvalued: when the economy weakened and people lost income or their jobs, they couldn’t make the mortgage payments. And, to make things worse, the value of the real estate sometimes sank too, so that the debtors owed more on the property than it was worth (that’s called being underwater). They couldn’t sell without taking a loss, and they couldn’t make the payments. Some debtors just walked away, leaving the banks with a large number of houses, commercial buildings, and even shopping centers on their hands.

The mortgage has ancient roots, but the form we know evolved from the English land law in the Middle Ages. Understanding that law helps to understand modern mortgage law. In the fourteenth century, the mortgage was a deed that actually transferred title to the mortgagee. If desired, the mortgagee could move into the house, occupy the property, or rent it out. But because the mortgage obligated him to apply to the mortgage debt whatever rents he collected, he seldom ousted the mortgagor. Moreover, the mortgage set a specific date (the “law day”) on which the debt was to be repaid. If the mortgagor did so, the mortgage became void and the mortgagor was entitled to recover the property. If the mortgagor failed to pay the debt, the property automatically vested in the mortgagee. No further proceedings were necessary.

This law was severe. A day’s delay in paying the debt, for any reason, forfeited the land, and the courts strictly enforced the mortgage. The only possible relief was a petition to the king, who over time referred these and other kinds of petitions to the courts of equity. At first fitfully, and then as a matter of course (by the seventeenth century), the equity courts would order the mortgagee to return the land when the mortgagor stood ready to pay the debt plus interest. Thus a new right developed: the equitable right of redemption, known for short as the equity of redemption. In time, the courts held that this equity of redemption was a form of property right; it could be sold and inherited. This was a powerful right: no matter how many years later, the mortgagor could always recover his land by proffering a sum of money.

Understandably, mortgagees did not warm to this interpretation of the law, because their property rights were rendered insecure. They tried to defeat the equity of redemption by having mortgagors waive and surrender it to the mortgagees, but the courts voided waiver clauses as a violation of public policy. Hence a mortgage, once a transfer of title, became a security for debt. A mortgage as such can never be converted into a deed of title.

The law did not rest there. Mortgagees won a measure of relief in the development of the foreclosureTo shut off the owner’s interest in property and sell it upon default.. On default, the mortgagee would seek a court order giving the mortgagor a fixed time—perhaps six months or a year—within which to pay off the debt; under the court decree, failure meant that the mortgagor was forever foreclosed from asserting his right of redemption. This strict foreclosureThe creditor takes the collateral, discharges the debtor, and has no right to seek any deficiency. gave the mortgagee outright title at the end of the time period.

In the United States today, most jurisdictions follow a somewhat different approach: the mortgagee forecloses by forcing a public sale at auction. Proceeds up to the amount of the debt are the mortgagee’s to keep; surplus is paid over to the mortgagor. Foreclosure by saleTo sell land upon buyer’s default at a public auction. is the usual procedure in the United States. At bottom, its theory is that a mortgage is a lien on land. (Foreclosure issues are further discussed in Section 20.2 "Priority, Termination of the Mortgage, and Other Methods of Using Real Estate as Security".)

Under statutes enacted in many states, the mortgagor has one last chance to recover his property, even after foreclosure. This statutory right of redemptionAfter foreclosure, for a limited period, the debtor’s right to reclaim the property sold, upon paying all costs and fees. extends the period to repay, often by one year.

The decision whether to lend money and take a mortgage is affected by several federal and state regulations.

Statutes dealing with consumer credit transactions (as discussed in Chapter 18 "Consumer Credit Transactions") have a bearing on the mortgage, including state usury statutes, and the federal Truth in Lending Act and Equal Credit Opportunity Act.

Other federal statutes are directed more specifically at mortgage lending. One, enacted in 1974, is the Real Estate Settlement Procedures Act (RESPA), aimed at abuses in the settlement process—the process of obtaining the mortgage and purchasing a residence. The act covers all federally related first mortgage loans secured by residential properties for one to four families. It requires the lender to disclose information about settlement costs in advance of the closing day: it prohibits the lender from “springing” unexpected or hidden costs onto the borrower. The RESPA is a US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) consumer protection statute designed to help home buyers be better shoppers in the home-buying process, and it is enforced by HUD. It also outlaws what had been a common practice of giving and accepting kickbacks and referral fees. The act prohibits lenders from requiring mortgagors to use a particular company to obtain insurance, and it limits add-on fees the lender can demand to cover future insurance and tax charges.

Redlining. Several statutes are directed to the practice of redliningThe alleged practice by lenders not to lend within certain geographic areas; considered discrimination.—the refusal of lenders to make loans on property in low-income neighborhoods or impose stricter mortgage terms when they do make loans there. (The term derives from the supposition that lenders draw red lines on maps around ostensibly marginal neighborhoods.) The most important of these is the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) of 1977.12 United States Code, Section 2901. The act requires the appropriate federal financial supervisory agencies to encourage regulated financial institutions to meet the credit needs of the local communities in which they are chartered, consistent with safe and sound operation. To enforce the statute, federal regulatory agencies examine banking institutions for CRA compliance and take this information into consideration when approving applications for new bank branches or for mergers or acquisitions. The information is compiled under the authority of the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act of 1975, which requires financial institutions within its purview to report annually by transmitting information from their loan application registers to a federal agency.

The note and the mortgage documents are the contracts that set up the deal: the mortgagor gets credit, and the mortgagee gets the right to repossess the property in case of default.

If the lender decides to grant a mortgage, the mortgagor signs two critical documents at the closing: the note and the mortgage. We cover notes in Chapter 13 "Nature and Form of Commercial Paper". It is enough here to recall that in a note (really a type of IOU), the mortgagor promises to pay a specified principal sum, plus interest, by a certain date or dates. The note is the underlying obligation for which the mortgage serves as security. Without the note, the mortgagee would have an empty document, since the mortgage would secure nothing. Without a mortgage, a note is still quite valid, evidencing the debtor’s personal obligation.

One particular provision that usually appears in both mortgages and the underlying notes is the acceleration clauseA contract clause providing that the entire amount owing in debt becomes due if one payment is missed.. This provides that if a debtor should default on any particular payment, the entire principal and interest will become due immediately at the lender’s option. Why an acceleration clause? Without it, the lender would be powerless to foreclose the entire mortgage when the mortgagor defaulted but would have to wait until the expiration of the note’s term. Although the acceleration clause is routine, it will not be enforced unless the mortgagee acts in an equitable and fair manner. The problem arises where the mortgagor’s default was the result of some unconscionable conduct of the mortgagee, such as representing to the mortgagee that she might take a sixty-day “holiday” from having to make payments. In Paul H. Cherry v. Chase Manhattan Mortgage Group (Section 20.4 "Cases"), the equitable powers of the court were invoked to prevent acceleration.

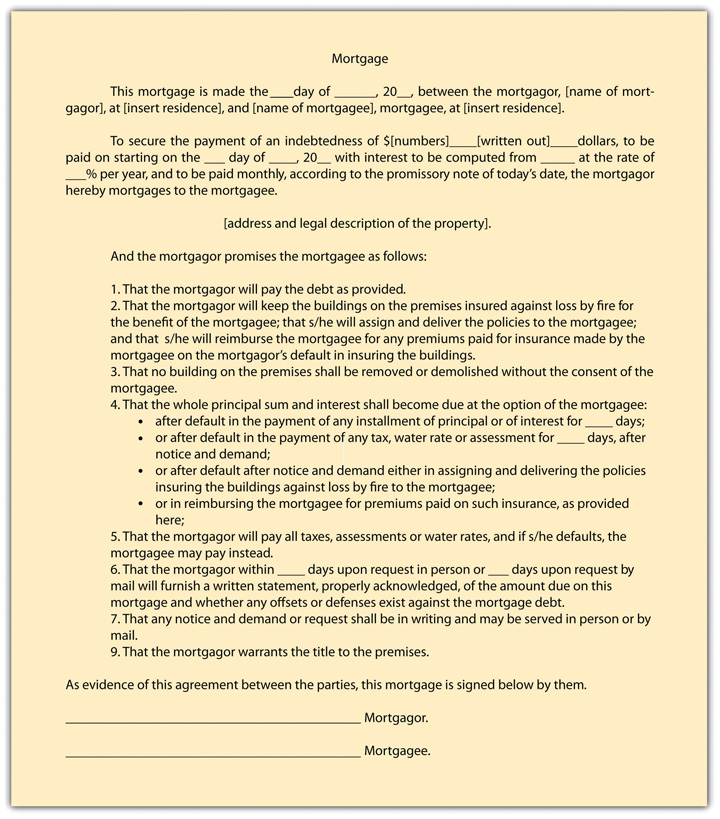

Under the statute of frauds, the mortgage itself must be evidenced by some writing to be enforceable. The mortgagor will usually make certain promises and warranties to the mortgagee and state the amount and terms of the debt and the mortgagor’s duties concerning taxes, insurance, and repairs. A sample mortgage form is presented in Figure 20.2 "Sample Mortgage Form".

Figure 20.2 Sample Mortgage Form

As a mechanism of security, a mortgage is a promise by the debtor (mortgagor) to repay the creditor (mortgagee) for the amount borrowed or credit extended, with real estate put up as security. If the mortgagor doesn’t pay as promised, the mortgagee may repossess the real estate. Mortgage law has ancient roots and brings with it various permutations on the theme that even if the mortgagor defaults, she may nevertheless have the right to get the property back or at least be reimbursed for any value above that necessary to pay the debt and the expenses of foreclosure. Mortgage law is regulated by state and federal statute.