What do you do when you are ill? You might first go to a drugstore, browse the shelves a bit, and find an over-the-counter medication that you think will make you feel better. Your choice of product could be influenced by many things, including past experience, the advice of friends, or perhaps an advertisement you saw on television.

If the trip to the drugstore doesn’t solve the problem, a visit to a doctor usually comes next. The first doctor you visit is likely to be a general practitioner, or GP for short. Even if insurance is picking up some of the cost, a trip to the doctor is often not cheap. Nor is it usually fun: it may involve long waits and unpleasant tests. We go to the doctor not because we enjoy the experience in itself but because of a deeper demand—a desire to be healthy.

A trip to the doctor typically ends with a bill, a prescription, and perhaps a smile along with a “see you again soon.” (That last bit, of course, is not quite what you want to hear.) Then you go to the pharmacy to fill the prescription. If you look at the piece of paper the doctor gave you, you might notice a couple of things. First, the doctor’s handwriting is often illegible; penmanship is evidently not high on the list of topics taught at a medical school. Second, even if you can read what is written, it probably means nothing to you. The chances are that it probably names some medication you have never heard of—and even if you have heard of it, you probably have no idea what the medication does or how it works.

In other words, though you are the purchaser and the patient, your treatment is largely out of your hands. Health-care purchases do not directly reflect individual choices the way most other spending decisions do. You did not choose to be sick, and you do not choose your treatment either.

Occasionally, your GP might recommend that you visit another doctor, called a specialist. Your GP might try to explain the basis of this recommendation, but you probably lack the expertise and the knowledge to evaluate the decision. Once again, you must trust your doctor to make a good decision for you: the decision to visit the specialist is largely your doctor’s rather than your own. You typically follow the doctor’s advice for two reasons: (1) you trust the doctor to make decisions in your best interest, and (2) if you have medical insurance, you do not have to pay most of the costs.

We have described this as though you have no control at all over your own health care and treatment. This is an exaggeration. If you are somewhat informed or knowledgeable about what is wrong with you, then you can discuss different treatment options with your doctors. You can become at least somewhat informed by reading articles on the Internet. You can seek out second and third opinions if you do not trust your doctor’s diagnosis. If you are having serious treatments, such as a surgical procedure, you will have to sign forms consenting to the treatment. There is a trend these days for people to become more involved and empowered about decisions involving their own health. Yet, unless you have medical training yourself, you will have to rely to some degree, and probably a very large degree, on the advice of your doctors.

If you are seriously ill, you may have to go to the hospital. There you have access to many more specialists as well as a lot of specialized equipment. Whatever autonomy you had about your treatment largely disappears once you enter the hospital. At this point—at least if you are living in the United States—you certainly should hope you have insurance coverage. Hospital costs can be astounding.

If you look back in history, health care was not always provided the way it is today. One difference is that doctors used to visit patients at home. They would traditionally arrive with a small black bag containing their basic tools. (This type of service is still provided in some communities and in some countries, but it is now rare in the United States.) For the most part, that was where your medical treatment ended.

In part, this reflected the state of medical knowledge at the time. It is hard to comprehend how much medical science has advanced in the last century. One hundred years ago, our knowledge about the workings of the human body was rudimentary. There were few treatments available. Antibiotics had not yet been discovered, which meant that the simplest injury—even a scratch—could become infected and be fatal. If you had appendicitis, it would very likely kill you. There were few means of diagnosis and no treatments for cancer.

Today, the story is very different. We visit specialists who have highly advanced (and expensive) training. We have access to advanced diagnostic tools, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans, blood tests that identify markers for cancer, and genetic testing. We also have access to expensive treatments, such as kidney dialysis and radiation therapy. Perhaps most strikingly, we have access to a range of pharmaceutical products that have been developed—sometimes at great expense—by scientists and researchers. These products can treat medical conditions from asthma to apnea to acne.

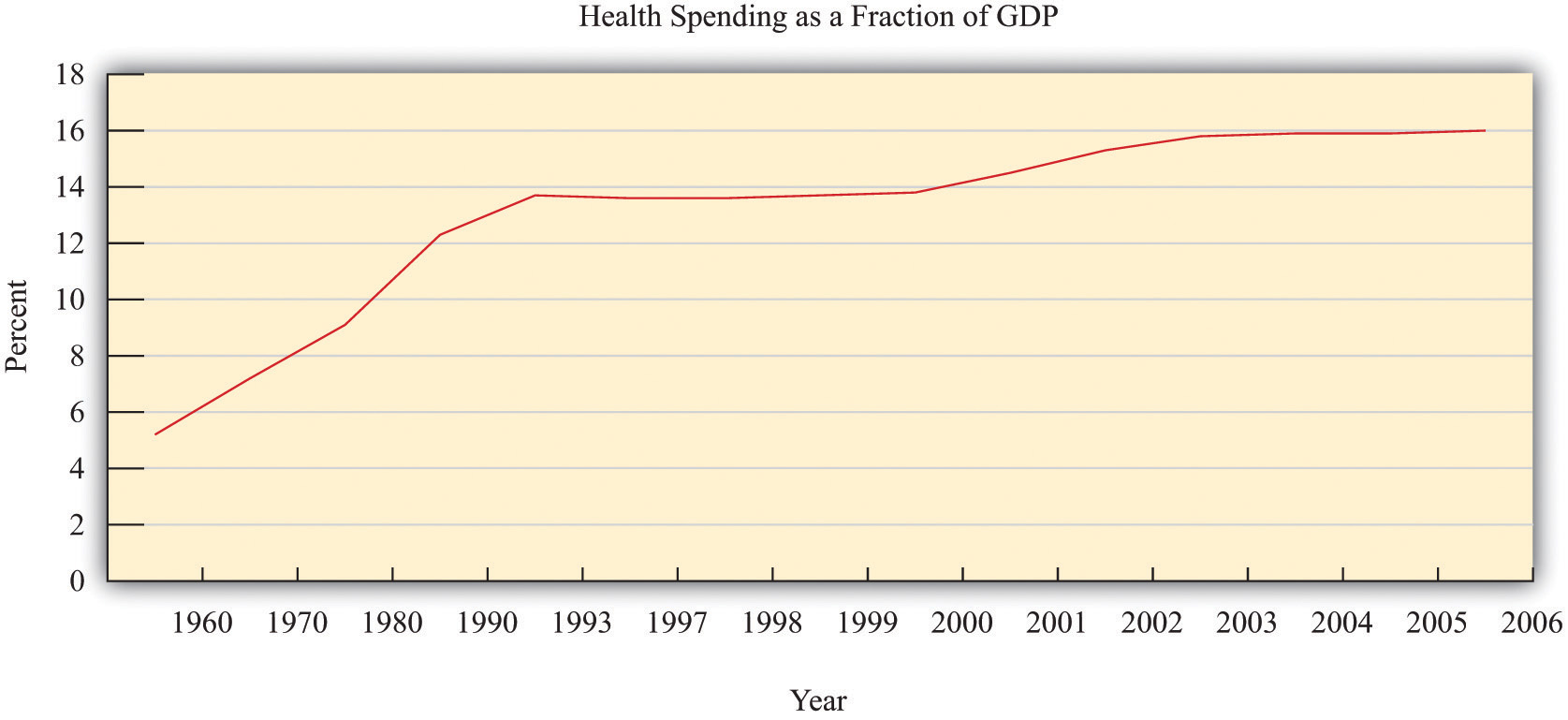

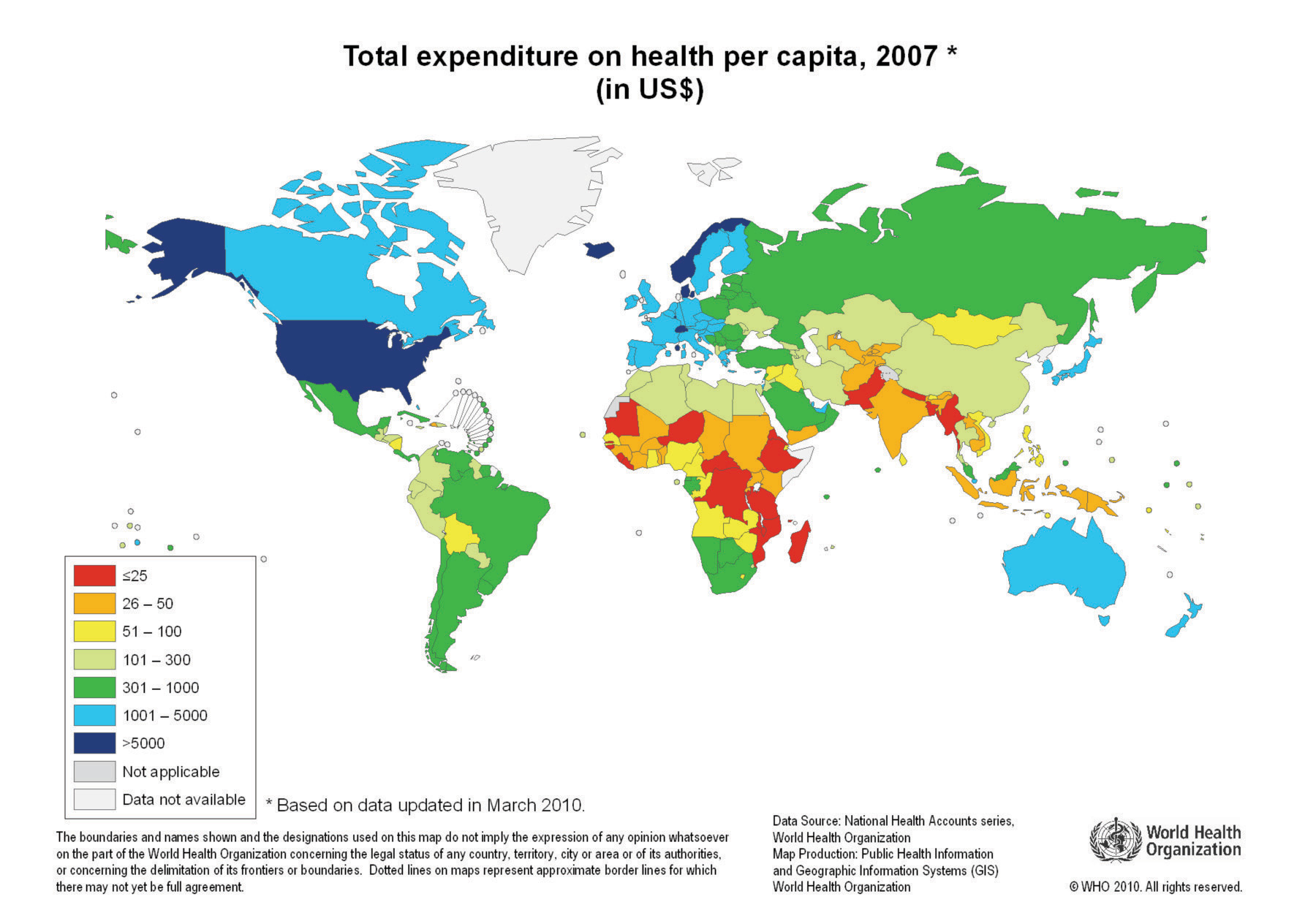

With all these visits to doctors and all these medications, we spend a great deal on health care. Spending as a fraction of gross domestic product (GDP; a measure of the total output of the economy) has been increasing since 1960 (Figure 16.1 "US Health-Care Expenses as a Percentage of GDP"). Figure 16.2 "Global Health-Care Spending" shows total spending on health services per person around the world.World Health Organization, “Total Expenditure on Health per Capita, 2007 (in US$),” accessed March 1, 2011, http://www.who.int/nha/use/the_pc_2007.png. The shaded areas indicate the level of spending on health-care services. The United States spends the most on health care per person, with Norway and Switzerland also being high-spending countries. Other rich countries, such as Japan, Australia, New Zealand, South Korea, and countries in Western Europe, likewise spend relatively large amounts on health care. The poorer countries in the world, not surprisingly, spend much less per person on health care. Across countries in the world, as within a country, health-care purchases are related to income.

Figure 16.1 US Health-Care Expenses as a Percentage of GDP

Figure 16.2 Global Health-Care Spending

One reason that we spend so much on health care in the United States is that high-quality care, such as is available in rich countries, is at least in part a luxury good—that is, something that we spend relatively more on as our income increases. Yet even across relatively affluent countries, health care takes very different forms.A comparison of programs is provided by Ed Cooper and Liz Taylor, “Comparing Health Care Systems: What Makes Sense for the US?” In Context, accessed March 14, 2011, http://www.context.org/ICLIB/IC39/CoopTalr.htm. Compare, for example, the United States and Canada. Canada has a system in which the government pays for health care. The program is financed by the payment of taxes to the government. Doctors’ fees are set by the government, which limits competition within the health industry. Furthermore, other developed countries spend much less on health care than the United States but have health outcomes that are as good or even better.

Differences in both the quality and cost of health care mean that, perhaps surprisingly, health care is traded across national boundaries. In some cases, people travel across the globe to obtain care in other countries. Sometimes, people travel to obtain treatments that are unavailable in their home countries. For example, US residents sometimes travel to other countries to obtain stem-cell treatments that are banned in the United States. Or people may seek health care in other countries simply because it is cheaper: people from around the world travel to Thailand, for example, to obtain cheap and reliable dentistry services. There are even tour operators that arrange such “health tourism” trips.National Public Radio had a March 18, 2008, story of a husband and wife going to China for get stem-cell treatment for their seven-month-old daughter (http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=88123868). There is also a company that organizes trips to Canada (http://www.findprivateclinics.ca/resources/general/medical-tourism.php). Given all these differences in health care costs around the world, we address the following question in this chapter:

What determines the cost of health care?

Because we want to talk about the price of health care, supply and demand is a natural starting point. As we use this framework, though, it will rapidly become clear that there are many things that are unique about the market for health care. One indication of this is that there is a whole subfield of economics called “health economics.” There is no subfield called “chocolate bar economics,” “tax advice economics,” or “lightbulb economics.” Evidently, there is something different about health care. Another indication is the fact that governments around the world pay an enormous amount of attention to this market. Governments intervene extensively in this market through taxes, through subsidies, and sometimes by being the direct provider of health-care services.

We first study the demand for health care by households. Then we look at the supply of health care, after which we turn to the determination of prices. As we proceed, we will see that health care includes all sorts of different products and services. We will also see that there are many reasons why it is difficult to analyze health care with a simple supply-and-demand framework.

One key reason why health care is such a complicated topic has to do with the fact that, frequently, we do not pay for health care ourselves. Rather, we (or our employers) purchase health insurance, and then the insurance company pays the health-care providers. We therefore discuss health insurance in some detail. The chapter ends with a discussion of the government’s role in the health sector, in which we talk about market failures and a variety of proposed government solutions.