At the end of this section, students should be able to meet the following objectives:

Question: In an accounting system, the impact of each transaction is analyzed and must then be recorded. Debits and credits are used for this purpose. How does the actual recording of a transaction take place?

Answer: The effects produced on the various accounts by a transaction should be entered into the accounting system as quickly as possible so that information is not lost and mistakes have less time to occur. After analyzing each event, the financial changes caused by a transaction are initially recorded as a journal entryThe physical form used initially in double-entry bookkeeping to record the financial changes caused by a transaction; must have at least one debit and one credit and the total debit(s) always equal the total credit(s)..In larger organizations, similar transactions are often grouped, summed, and recorded together for efficiency. For example, all cash sales at one store might be totaled automatically and recorded at one time at the end of each day. To help focus on the mechanics of the accounting process, the journal entries recorded for the transactions in this textbook will be prepared individually. A list of all recorded journal entries is maintained in a journalThe physical location of all journal entries; the diary of an organization capturing the impact of financial events as they took place; it is also referred to as the general journal. (also referred to as a general journalThe physical location of all journal entries; the diary of a company capturing the impact of financial events as they took place; it is also referred to as the journal.), which is one of the most important components within any accounting system. The journal is the diary of the company: the history of the impact of the financial events as they took place.

A journal entry is no more than an indication of the accounts and balances that were changed by a transaction.

Question: Debit and credit rules are best learned through practice. In order to grasp the use of debits and credits, how should the needed practice begin?

Answer: When faced with debits and credits, everyone has to practice at first. That is normal and to be expected. These rules can be learned quickly but only by investing a bit of effort. Earlier in this chapter, a number of transactions were analyzed to determine their impact on account balances. Assume now that these same transactions are to be recorded as journal entries. To provide a bit more information for this illustration, the reporting company will be a small farm supply store known as the Lawndale Company that is located in a rural area. For convenience, assume that the company incurs these transactions during the final few days of Year One, just prior to preparing financial statements.

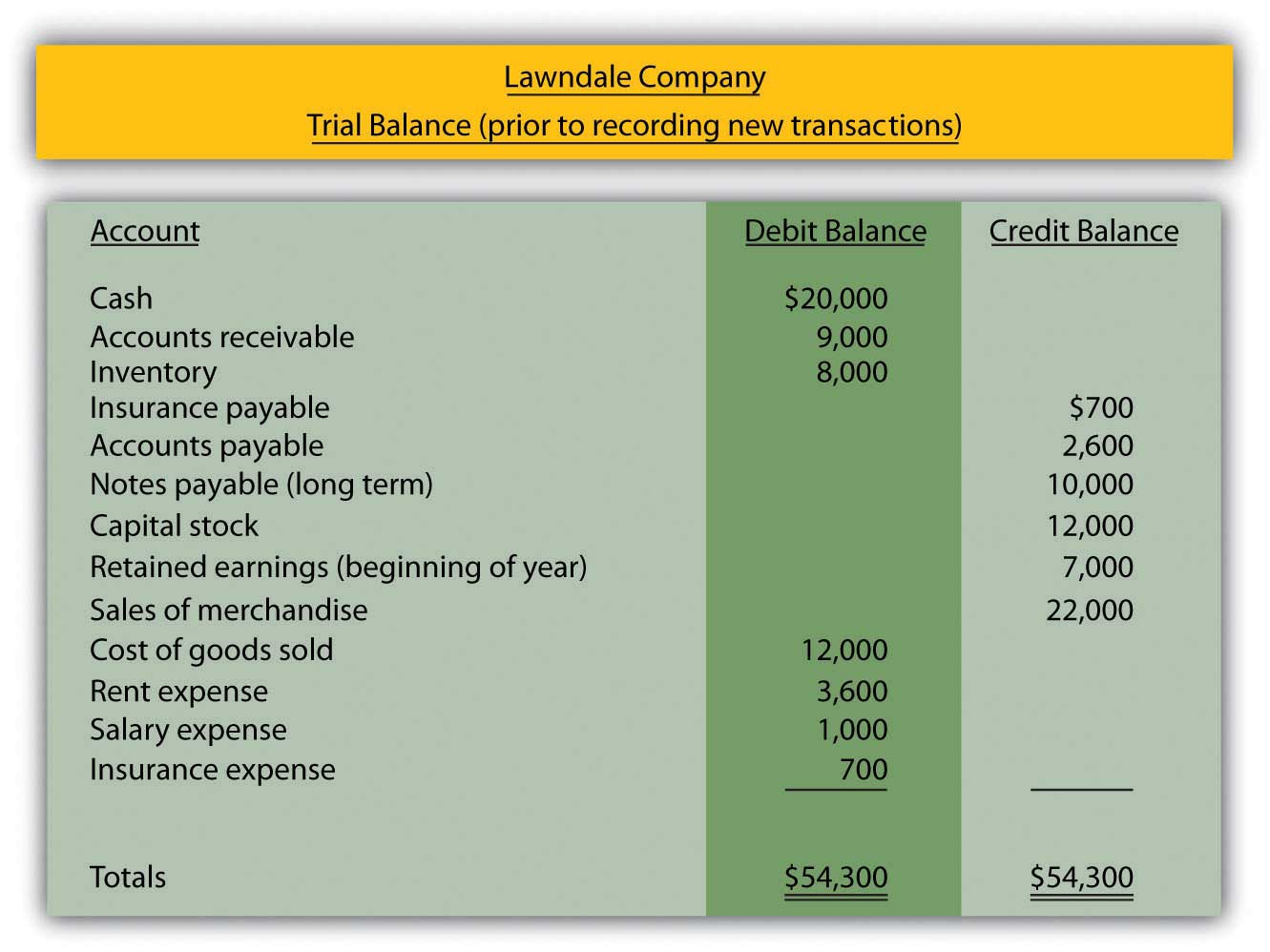

Assume further that this company already has the account balances presented in Figure 4.3 "Balances Taken From T-accounts in Ledger" in its T-accounts before making this last group of journal entries. Note that the total of all the debit and credit balances do agree ($54,300) and that every account shows a positive balance. In other words, the figure being reported is either a debit or credit based on what makes that particular type of account increase. Few T-accounts contain negative balances.

This current listing of accounts is commonly referred to as a trial balanceList of account balances as shown at a point in time for each of the T-accounts maintained in the company’s ledger; eventually, financial statements are created using these balances.. Since T-accounts are kept together in a ledger (or general ledger), a trial balance reports the individual balances for each T-account maintained in the company’s ledger.

Figure 4.3 Balances Taken From T-accounts in Ledger

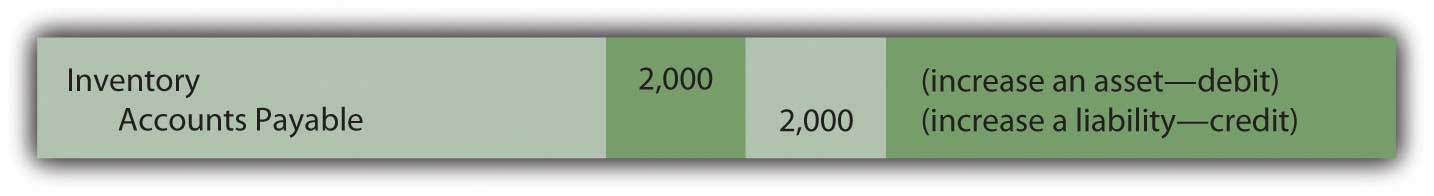

Question: Assume that after the above balances were determined, several additional transactions took place. The first transaction analyzed at the start of this chapter was the purchase of inventory on credit for $2,000. This acquisition increases the record of the amount of inventory being held while also raising one of the company’s liabilities, accounts payable. How is the acquisition of inventory on credit recorded in the form of a journal entry?

Answer: Following the transactional analysis, a journal entry is prepared to record the impact that the event has on the Lawndale Company. Inventory is an asset that always uses a debit to note an increase. Accounts payable is a liability so that a credit indicates that an increase has occurred. Thus, the following journal entry is appropriate. The parenthetical information is included here only for clarification purposes and does not appear in a true journal entry.

Figure 4.4 Journal Entry 1: Inventory Acquired on Credit

Notice that the word “inventory” is physically on the left of the journal entry and the words “accounts payable” are indented to the right. This positioning clearly shows which account is debited and which is credited. In the same way, the $2,000 numerical amount added to the inventory total appears on the left (debit) side whereas the $2,000 change in accounts payable is clearly on the right (credit) side.

Preparing journal entries is obviously a mechanical process but one that is fundamental to the gathering of information for financial reporting purposes. Any person familiar with accounting procedures could easily “read” the above entry: based on the debit and credit, both inventory and accounts payable have gone up so a purchase of merchandise for $2,000 on credit is indicated. Interestingly, with translation of the words, a Venetian merchant from the later part of the fifteenth century would be capable of understanding the information captured by this journal entry even if prepared by a modern company as large as Xerox or Kellogg.

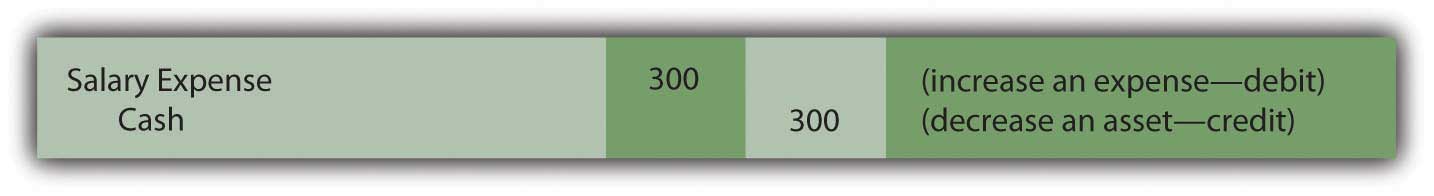

Question: As a second example, the Lawndale Company pays its employees their regular salary of $300 for work performed during the past week. If no entry has been recorded previously, what journal entry is appropriate when a salary payment is made?

Answer: Because no entry has yet been made, neither the $300 salary expense nor the related salary payable already exists in the accounting records. Apparently, the $1,000 salary expense appearing in the above trial balance reflects earlier payments made during the period by the company to its employees.

Payment is made here for past work so this cost represents an expense rather than an asset. Thus, the balance recorded as salary expense goes up by this amount while cash decreases. Increasing an expense is always shown by means of a debit; decreasing an asset is reflected through a credit.

Figure 4.5 Journal Entry 2: Salary Paid to Employees

In practice, the date of each transaction could also be included here. For illustration purposes, this extra information is not necessary.

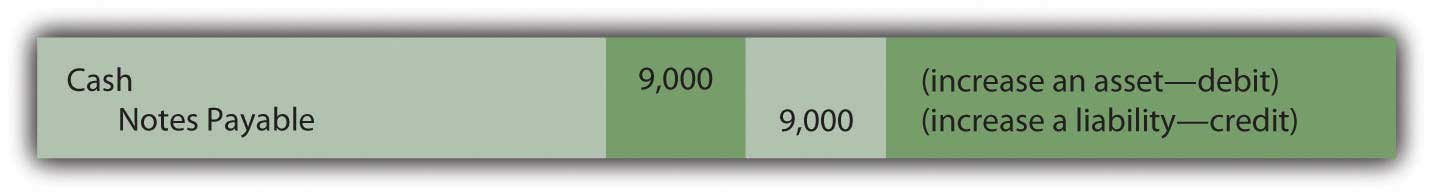

Question: Assume $9,000 is borrowed from a local bank when officials sign a new note payable that will have to be repaid in several years. What journal entry is prepared by a company’s accountant to reflect the inflow of cash received from a loan?

Answer: As always, recording begins with an analysis of the transaction. Here, cash increases as the result of the incurred debt (notes payable). Cash—an asset—increases $9,000, which is shown as a debit. The company’s notes payable balance also goes up by the same amount. As a liability, the increase is recorded through a credit. By using debits and credits in this way, the financial effects are entered into the accounting records.

Figure 4.6 Journal Entry 3: Money Borrowed from Bank

Link to multiple-choice question for practice purposes: http://www.quia.com/quiz/2092610.html

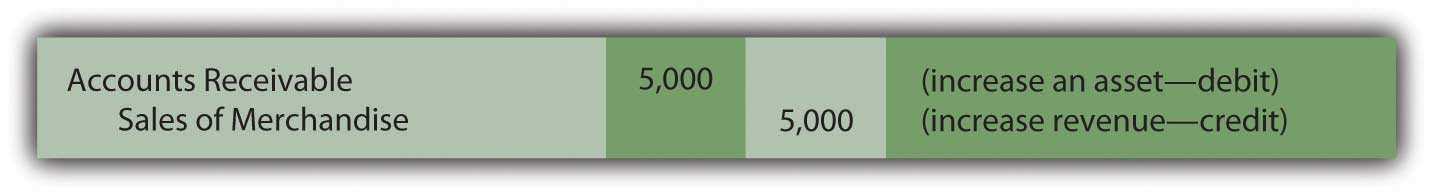

Question: In Transaction 1, inventory was bought for $2,000. That entry is recorded above. Assume now that these goods are sold for $5,000 to a customer on credit. How is the sale of merchandise on account recorded in journal entry form?

Answer: As discussed previously, two events really happen when inventory is sold. First, the sale is made and, second, the customer takes possession of the merchandise from the company. Assuming again that a perpetual inventory system is in use, both the sale and the related expense are recorded immediately. In the initial part of the transaction, the accounts receivable balance goes up $5,000 because the money from the customer will not be collected until a later date. The increase in this asset is shown by means of a debit. The new receivable resulted from a sale. Revenue is also recorded (by a credit) to indicate the cause of that effect.

Figure 4.7 Journal Entry 4A: Sale Made on Account

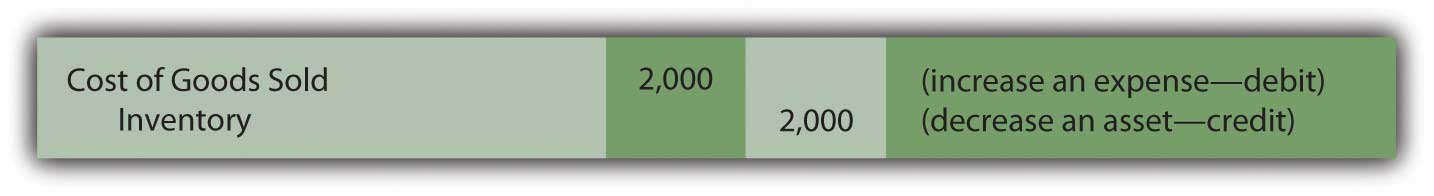

At the same time, inventory costing $2,000 is surrendered by the company. The reduction of any asset is recorded through a credit. The expense resulting from the asset outflow has been identified previously as “cost of goods sold.” Like any expense, it is entered into the accounting system through a debit.

Figure 4.8 Journal Entry 4B: Merchandise Acquired by Customers

Question: In the above transaction, the Lawndale Company made a sale but the cash will not be collected until some later date. Why is revenue reported at the time of sale rather than when the cash is eventually collected? Accounting is conservative. Thus, delaying recognition of sales revenue (and the resulting increase in net income) until the $5,000 is physically received might have been expected.

Answer: This question reflects a common misconception about the information conveyed through financial statements. As shown above in Journal Entry 4A, recognition of revenue is not tied directly to the receipt of cash. One of the most important elements comprising the structure of U.S. GAAP is accrual accountingSystem required by U.S. GAAP to standardize the timing of the recognition of revenues and expenses; it is made up of the revenue realization principle and the matching principle., which serves as the basis for timing the reporting of revenues and expenses. Because of the direct impact on net income, such recognition issues are among the most complicated and controversial in accounting. The accountant must always determine the appropriate point in time for reporting each revenue and expense. Accrual accounting provides standard guidance (in the United States and throughout much of the world).

Accrual accounting is really made up of two distinct components. The revenue realization principleThe portion of accrual accounting that guides the timing of revenue recognition; it states that revenue is properly recognized at the point that the earning process needed to generate the revenue is substantially complete and the amount to be received can be reasonably estimated. provides authoritative direction as to the proper timing for the recognition of revenue. The matching principleThe portion of accrual accounting that guides the timing of expense recognition; it states that expense is properly recognized in the same time period as the revenue that it helped generate. establishes guidelines for the reporting of expenses. These two principles have been utilized for decades in the application of U.S. GAAP. Their importance within financial accounting can hardly be overstated.

Revenue realization principle. Revenue is properly recognized at the point that (1) the earning process needed to generate the revenue is substantially complete and (2) the amount eventually to be received can be reasonably estimated. As the study of financial accounting progresses into more complex situations, both of these criteria will require careful analysis and understanding.

Matching principle. Expenses are recognized in the same time period as the revenue they help create. Thus, if specific revenue is to be recognized in the year 2019, any associated costs should be reported as expenses in that same time period. Expenses are matched with revenues. However, when a cost cannot be tied directly to identifiable revenue, matching is not possible. In those cases, the expense is recognized in the most logical time period, in some systematic fashion, or as incurred—depending on the situation.

For the revenue reported in Journal Entry 4A, assuming that the Lawndale Company has substantially completed the work required of this sale and $5,000 is a reasonable estimate of the amount that will be collected, recognition at the time of sale is appropriate. Because the revenue is recognized at that moment, the related expense (cost of goods sold) should also be recorded as can be seen in Journal Entry 4B.

Accrual accounting provides an excellent example of how U.S. GAAP guides the reporting process in order to produce fairly presented financial statements that can be understood by all decision makers around the world.

Link to multiple-choice question for practice purposes: http://www.quia.com/quiz/2092642.html

After the financial effects are analyzed, the impact of each transaction is recorded within a company’s accounting system through a journal entry. The purchase of inventory, payment of a salary, and borrowing of money are all typical transactions that are recorded by means of debits and credits. All journal entries are maintained within the company’s journal. The timing of this recognition is especially important in connection with revenues and expenses. Accrual accounting provides formal guidance within U.S. GAAP. Revenues are recognized when the earning process is substantially complete and the amount to be collected can be reasonably estimated. Expenses are recognized based on the matching principle, which holds that they should be reported in the same period as the revenue they help generate.