As in previous chapters, this concluding section lays out seven practices that are consistent with the chapter’s focus, systems thinking, which can make your organization more change capable.

Unintended side effects are common with pharmaceuticals, so why should we be surprised when the same thing happens during or after an organizational change initiative is launched? Organizations are complex, interdependent social systems. Like a water balloon, when we push on one part of it, another part changes. While anticipating the side effects of a change initiative is not easy to do, some effort should be made to envision what those ripple effects might be.

Similar to scenario analysis of future environmental states,Schwartz (1991). by envisioning potential outcomes in advance we are more prepared to deal with the outcomes that may result. Furthermore, by trying to anticipate future unintended consequences, sponsors of the change and the change agents are more attentive to the unfolding nature of the change initiative and more likely to learn from the experience.Schriefer and Sales (2006). It is important to remember, however, that cause and effect are often not closely related in time and space when trying to change a complex system. Consequently, analogies can be a useful tool for anticipating unintended consequences of change. Another tool for anticipating the effects of a change initiative are computerized simulations.Ziegenfuss and Bentley (2000).

One systems thinking tool that can be instrumental in anticipating ripple effects are causal loop diagramsA systems thinking tool that can help an organization visualize in advance the potential outcomes of change..Hebel (2007). Diagrams help us to visualize how the change might unfold. Causal loops remind us that there are feedback linkages within systems that can dampen or amplify the effects of initiatives. In sum, anticipating ripple effects is more art than science, but the effort will ensure that unintended side effects are avoided and will deepen the change sponsors’ understanding of the systemic nature of change.

There are no simple rules for finding high-leverage changes, but there are ways of thinking that make it more likely. Learning to see underlying “structures” rather than “events” is a starting point…Thinking in terms of processes of change rather than “snapshots” is another.Senge (1990), p. 65.

Malcolm Gladwell wrote a best-selling book on this very topic and it was given the graphic term “tipping points.” Gladwell argues that “the world may seem like an immovable, implacable place. It is not. With the slightest push—in just the right place—it can be tipped.”Gladwell (2002), p. 259.

Gladwell also asserts that ideas, products, messages, and behaviors can spread just like viruses do. Similar to how the flu attacks kids in schools each winter, the small changes that tip the system must be contagious; they should multiply rapidly; and the contagion should spread relatively quickly through a population within a particular system. Learning how your system has tipped in the past, and understanding who or what was involved can be an invaluable insight into thinking systemically about your organization.

Systemic change often involves multiple feedback loopsA type of message assessment that is essential in uncovering what was heard, what was remembered, and what new behaviors, if any, have resulted. Feedback loops are essential to change initiatives because they provide information that will allow change designers to broaden or refine their perspective. and drivers of change. As such, focusing on a single causal variable is often not helpful. For example, I often hear executives argue that “it is all about the right reward systems—get your rewards right and everything falls into place.” While reward systems are very important and a key part of organizational change capability, they are a subsystem within a larger system that has many complex and interacting parts.

Barry Oshry writes insightfully about “spatial” and “temporal” blindness within an organizational system. Spatial blindness is about seeing the part without seeing the whole. Temporal blindness is about seeing the present without the past. Both forms of blindness need to be overcome in order to better understand cause and effect within a system. Oshry recommends that people from various parts of the system need to periodically take time out to reflect collectively so as to transcend their blind spots.Oshry (1996), p. 27.

Change is difficult and often painful. People generally will not give up an idea, behavior, or mental model without latching onto something to replace it. The something that they need to hold onto is the shared vision of the future. In their analysis of over 10,000 successful change initiatives in organizations, Jim Kouzes and Barry Posner found that the creation of an inspiring vision of the future was always present.Kouzes and Posner (2003). As Peter Senge notes, “When there is a genuine vision (as opposed to the all-too-familiar ‘vision statement’), people excel and learn, not because they are told to, but because they want to.”Senge (1990), p. 9. And Jim Collins and Gerry Porras point out that “a visionary company doesn’t simply balance between idealism and profitability; it seeks to be highly idealistic and highly profitable.”Collins and Porras (1994), p. 44. In sum, a compelling and well communicated vision is key to bringing about change within an organizational system, and this principle is central to systems thinking.

The definition of insanity is applying the same approach over and over again, and expecting new results—the same is true about mental models. When organizational changes don’t work or when an organization repeatedly fails to meet its performance expectations, sometimes the dominant mental model, or paradigm, within an organization is to blame. Changing this dominant mental model is not easy since political capital is often tied up with particular models. First-order systems changesChanges that involve refinement of a system within an existing mental model. involve refinement of the system within an existing mental model. Second-order systems changesChanges that involve the unlearning of a previous mental model and its replacement with a new and improved version. involve the unlearning of a previous mental model, and its replacement with a new and improved version. These changes do not occur on their own—second-order learning requires intention and focus on the history and identity of the overall system.Gharajedaghi, 2007.

Barry Oshry writes poetically about the “dance of the blind reflex.” This reflex is a generalization of the mental models of various parts of the organizational system. Oshry argues that top executives generally feel burdened by the unmanageable complexity for which they are responsible. Meanwhile, frontline workers at the bottom of the organizational hierarchy feel oppressed by insensitive higher-ups. Furthermore, middle managers feel torn and fractionated as they attempt to link the tops to the bottoms. Furthermore, customers feel righteously done-to (i.e., screwed) by an unresponsive system. Interestingly, none of the four groups of players mentioned see their part in creating any of the “dance” described here.Oshry (1996), p. 54. However, there is a way out of this problem. As Oshry notes,

We sometimes see the dance in others when they don’t see it in themselves; just as they see the dance in us when we are still blind to it. Each of us has the power to turn on the lights for others.Oshry (1996), p. 123.

Peter Vaill uses the metaphor of “permanent white water” as an analogy for the learning environment that most organizations currently find themselves in. He argues that “learning to reflect on our own learning” is a fundamental skill that is required for simple survival. Vaill argues that learning about oneself in interaction with the surrounding world is the key to changing our mental models. He further suggests that the personal attributes that make this all possible are the willingness to risk, to experiment, to learn from feedback, and above all, to enjoy the adventure.Vaill (1996), p. 156.

Dialogue aimed at understanding the organizational system is fundamental to enhancing systems thinking. This dialogue should involve top executives, middle managers, frontline workers, and customers at repeated intervals. Organizational systems gurus, such as Deming, Senge, and Oshry, all agree that the key to systemic thinking is to involve a wide variety of voices within the system talking and listening to each other. Town hall meetings, weekend retreats, and organizational intranets are a common and increasingly popular means of engaging in dialogue about the system.

When an individual or group within the system engages with another individual or group within the system that is “not normal”; new information is created within that system. External to the system, when an individual or group engages with individuals, groups, or other organizations that are not normal, new information is created between the systems. This new information can lead to energy and matter transfer that counteracts systemic entropy.

Intrasystemic opennessA situation in which two departments agree to collaborate on a project that includes mutual benefits to each. occurs when two departments agree to collaborate on a project that contains mutual benefits to each. “Open door” policies are clearly a step in the right direction. Even a simple act of going to lunch with someone you have never dined with before can reduce system entropy. Extrasystemic opennessA situation in which new employees are hired, external consultants are engaged, and individuals attend trade association meetings or external training sessions. occurs when new employees are hired, when external consultants are engaged, and when individuals attend trade association meetings or external training sessions. The human tendency to stick with the known and familiar and maintain routine must be challenged by the continual creation of new connections.

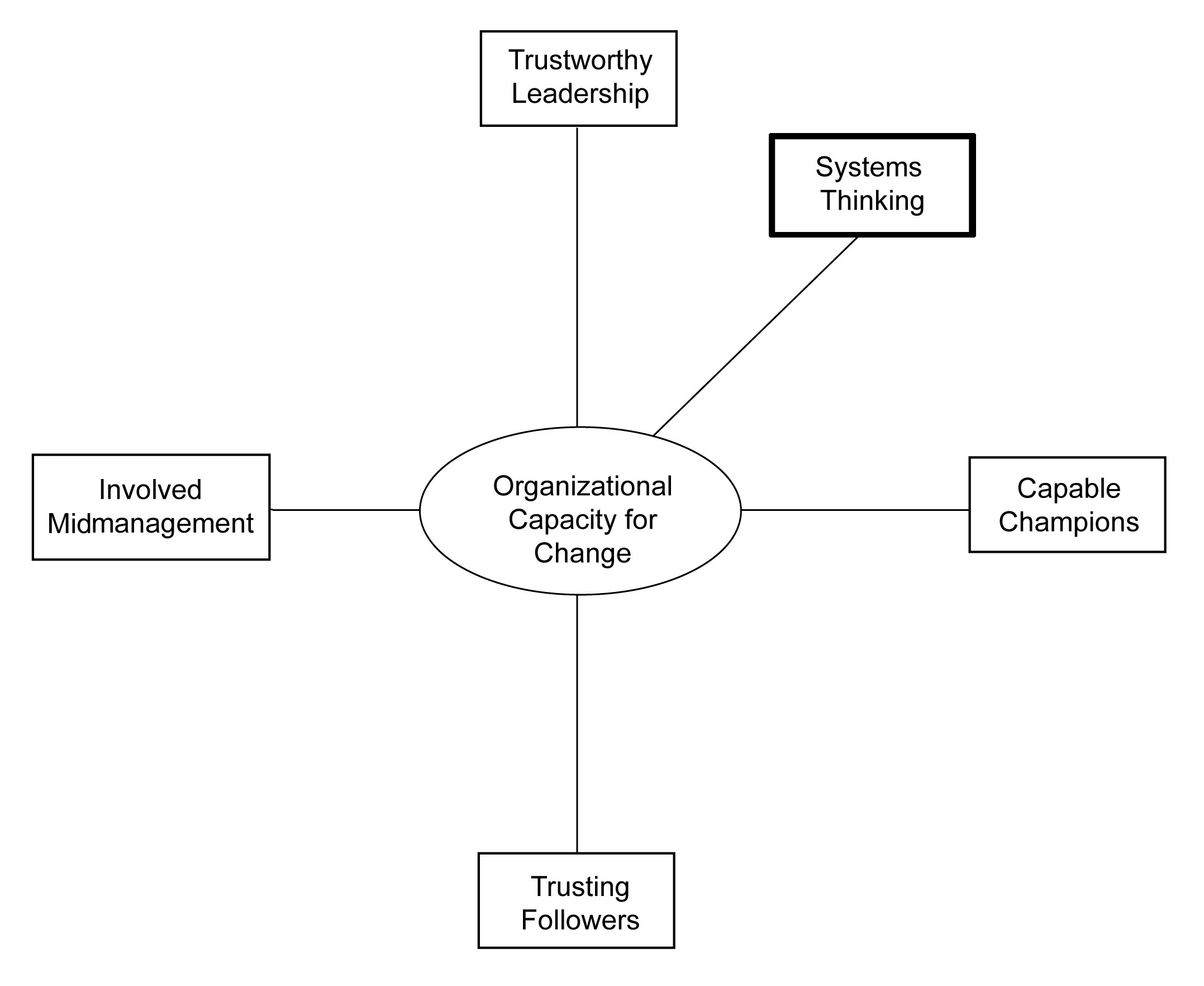

In sum, a systemic perspective is essential for making your organization change capable. Systems thinking is an infrastructure within which all change takes place. Figure 7.1 "The Fifth Dimension of Organizational Capacity for Change: Systems Thinking" contains a graphic summarizing this fifth dimension of organizational capacity for change.

Figure 7.1 The Fifth Dimension of Organizational Capacity for Change: Systems Thinking