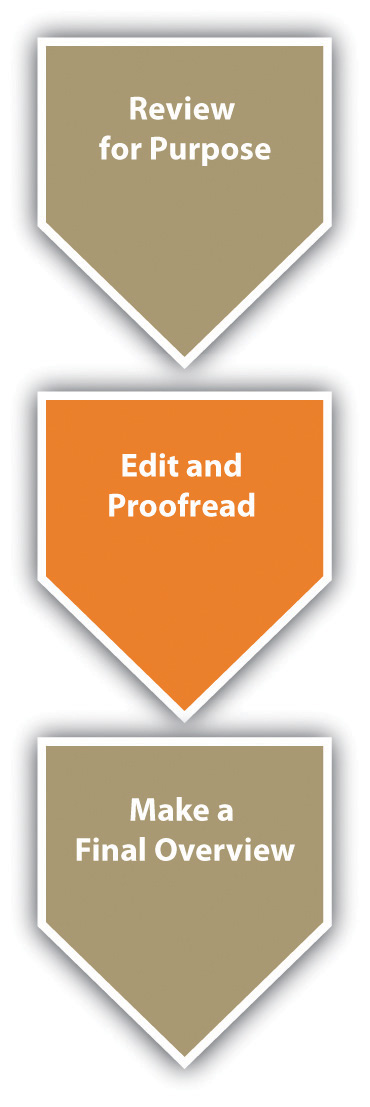

Every time you revise your work substantially, you will be conducting three distinct functions in the following order: reviewing for purpose, editing and proofreading, making a final overview.

Although you will naturally be reviewing for purposeConducting a complete examination of all aspects of your statement of purpose (voice, audience, message, tone, attitude, and reception) once you have written a complete first draft. throughout the entire writing process, you should read through your first complete draft once you have finished it and carefully reconsider all aspects of your essay. As you review for purpose, keep in mind that your paper has to be clear to others, not just to you. Try to read through your paper from the point of view of a member of your targeted audience who is reading your paper for the first time. Make sure you have neither failed to clarify the points your audience will need to have clarified nor overclarified the points your audience will already completely understand.

Figure 8.1

Self-questioningPosing questions during the review process that you intend to answer yourself. is a useful tool when you are in the reviewing process. In anticipation of attaching a writer’s memo to your draft as you send it out for peer or instructor review, reexamine the six elements of the triangle that made up your original statement of purpose (voice, audience, message, tone, attitude, and reception):

In many situations, you will be required to have at least one of your peers review your essay (and you will, in turn, review at least one peer’s essay). Even if you’re not required to exchange drafts with a peer, it’s simply essential at this point to have another pair of eyes, so find a classmate or friend and ask them to look over your draft. In other cases, your instructor may be intervening at this point with ungraded but evaluative commentary on your draft. Whatever the system, before you post or trade your draft for review, use your answers to the questions in Section 8.1 "Reviewing for Purpose".1 to tweak your original statement of purpose, giving a clear statement of your desired voice, audience, message, tone, attitude, and reception. Also, consider preparing a descriptive outlineA plan for an essay written after the fact, describing its organization. showing how the essay actually turned out and comparing that with your original plan, or consider writing a brief narrative describing how the essay developed from idea to execution. Finally, include any other questions or concerns you have about your draft, so that your peer reader(s) or instructor can give you useful, tailored feedback. These reflective statements and documents could be attached with your draft as part of a writer’s memo. Remember, the more guidance you give your readers, regardless of whether they are your peers or your instructor, the more they will be able to help you.

When you receive suggestions for content changes from your instructors, try to put aside any tendencies to react defensively, so that you can consider their ideas for revisions with an open mind. If you are accustomed only to getting feedback from instructors that is accompanied by a grade, you may need to get used to the difference between evaluationCommentary from a peer or instructor usually unaccompanied by a grade. and judgmentCommentary from an instructor usually leading to a quantitative assessment (grade) of your work.. In college settings, instructors often prefer to intervene most extensively after you have completed a first draft, with evaluative commentary that tends to be suggestive, forward-looking, and free of a final quantitative judgment (like a grade). If you read your instructors’ feedback in those circumstances as final, you can miss the point of the exercise. You’re supposed to do something with this sort of commentary, not just read it as the justification for a (nonexistent) grade.

Sometimes peers think they’re supposed to “sound like an English teacher” so they fall into the trap of “correcting” your draft, but in most cases, the prompts used in college-level peer reviewing discourage that sort of thing. (For more on the peer reviewReading through text written by a classmate or colleague looking for any changes that could be made to improve the writing. process and for a list of Twenty Questions for Peer Review, see Chapter 11 "Academic Writing", Section 11.3 "Collaborating on Academic Writing Projects".) In many situations, your peers will give you ideas that will add value to your paper, and you will want to include them. In other situations, your peers’ ideas will not really work into the plan you have for your paper. It is not unusual for peers to offer ideas that you may not want to implement. Remember, your peers’ ideas are only suggestions, and it is your essay, and you are the person who will make the final decisions. If your peers happen to be a part of the audience to which you are writing, they can sometimes give you invaluable ideas. And if they’re not, take the initiative to find outside readers who might actually be a part of your audience.

When you are reviewing a peer’s essay, keep in mind that the author likely knows more about the topic than you do, so don’t question content unless you are certain of your facts. Also, do not suggest changes just because you would do it differently or because you want to give the impression that you are offering ideas. Only suggest changes that you seriously think would make the essay stronger.

When you have made some revisions to your draft based on feedback and your recalibration of your purpose for writing, you may now feel your essay is nearly complete. However, you should plan to read through the entire final draft at least one additional time. During this stage of editing and proofreadingReading through text looking for mechanical errors (not content issues). your entire essay, you should be looking for general consistency and clarity. Also, pay particular attention to parts of the paper you have moved around or changed in other ways to make sure that your new versions still work smoothly.

Although you might think editing and proofreading isn’t necessary since you were fairly careful when you were writing, the truth is that even the very brightest people and best writers make mistakes when they write. One of the main reasons that you are likely to make mistakes is that your mind and fingers are not always moving along at the same speed nor are they necessarily in sync. So what ends up on the page isn’t always exactly what you intended. A second reason is that, as you make changes and adjustments, you might not totally match up the original parts and revised parts. Finally, a third key reason for proofreading is because you likely have errors you typically make and proofreading gives you a chance to correct those errors.

Figure 8.2

Editing and proofreading can work well with a partner. You can offer to be another pair of eyes for peers in exchange for their doing the same for you. Whether you are editing and proofreading your work or the work of a peer, the process is basically the same. Although the rest of this section assumes you are editing and proofreading your work, you can simply shift the personal issues, such as “Am I…” to a viewpoint that will work with a peer, such as “Is she…”

As you edit and proofread, you should look for common problem areas that stick out, including the quality writing components covered in Chapter 15 "Sentence Building", Chapter 16 "Sentence Style", Chapter 17 "Word Choice", Chapter 18 "Punctuation", Chapter 19 "Mechanics", and Chapter 20 "Grammar": sentence building, sentence style, word choice, punctuation, mechanics, and grammar (Chapter 15 "Sentence Building" through Chapter 20 "Grammar"). There are certain writing rules that you must follow, but other more stylistic writing elements are more subjective and will require judgment calls on your part.

Be proactive in evaluating these subjective, stylistic issues since failure to do so can weaken the potential impact of your essay. Keeping the following questions in mind as you edit and proofread will help you notice and consider some of those subjective issues:

While you are managing the content of your essay and moving things around in it, you are likely to notice isolated issues that could recur throughout your work. To verify that these issues are satisfactorily dealt with from the beginning to the end of your essay, make a checklist of the issues as you go along. Conduct isolated checks of the whole paper after you are finished editing and proofreading. You might conduct some checks by flipping through the hard-copy pages, some by clicking through the pages on your computer, and some by conducting “computer findsA search for a certain word or phrase within text that is located on a computer.” (good for cases when you want to make sure you’ve used the same proper noun correctly and consistently). Remember to take advantage of all the editing features of the word processing program you’re using, such as spell check (described in more detail in Chapter 19 "Mechanics", Section 19.1 "Mastering Commonly Misspelled Words") and grammar check. In most versions of Word, for instance, you’ll see red squiggly lines underneath misspelled words and green squiggly lines underneath misuses of grammar. Right click on those underlined words to examine your options for revision.

Figure 8.3

The following checklist shows examples of the types of things that you might look for as you make a final passA personalized self-review of a final draft, focusing on making isolated checks of common areas of difficulty you’ve had as a writer in the past. (or final passes) through your paper. It often works best to make a separate pass for each issue because you are less likely to miss an issue and you will probably be able to make multiple, single-issue passes more quickly than you can make one multiple-issue pass.

This isn’t intended to be an all-inclusive checklist. Rather, it simply gives you an idea of the types of things for which you might look as you conduct your final check. You should develop your unique list that might or might not include these same items.

Complete each sentence to create a logical item for a list to use for a final isolated check. Do not use any of the examples given in the text.