After studying this section you should be able to do the following:

Until 2009, Google hadn’t used tracking cookies on its AdSense network. While AdSense has been wildly successful, contextual advertising has its limits. For example, what kind of useful targeting can firms really do based on the text of a news item on North Korean nuclear testing?R. Singel, “Online Behavioral Targeting Targeted by Feds, Critics,” Wired News, June 3, 2009. So in March 2009, the firm announced what it calls “interest-based ads.” Google AdSense would now issue a third-party cookie and would track browsing activity across AdSense partner sites, and Google-owned YouTube. AdSense would build a profile, initially identifying users within thirty broad categories and six hundred subcategories. Says one Google project manager, “We’re looking to make ads even more interesting.”R. Hof, “Behavioral Targeting: Google Pulls Out the Stops,” BusinessWeek, March 11, 2009.

Figure 8.16 Categories for Google’s Interest-Based Advertising

Of course, there’s a financial incentive to do this too. Ads deemed more interesting should garner more clicks, meaning more potential customer leads for advertisers, more revenue for Web sites that run AdSense, and more money for Google.

But while targeting can benefit Web surfers, users will resist if they feel that they are being mistreated, exploited, or put at risk. Negative backlash might also result in a change in legislation. The U.S. Federal Trade Commission has already called for more transparency and user control in online advertising and for requesting user consent (opt-inProgram (typically a marketing effort) that requires customer consent. This program is contrasted with opt-out programs, which enroll all customers by default.) when collecting sensitive data.R. Singel, “Online Behavioral Targeting Targeted by Feds, Critics,” Wired News, June 3, 2009. Mishandled user privacy could curtail targeting opportunities, limiting growth across the online advertising field. And with less ad support, many of the Internet’s free services could suffer.

Google’s roll-out of interest-based ads shows the firm’s sensitivity to these issues. First, while major rivals have all linked query history to ad targeting, Google steadfastly refuses to do this. Other sites often link registration data (including user-submitted demographics such as gender and age) with tracking cookies, but Google avoids this practice as well.

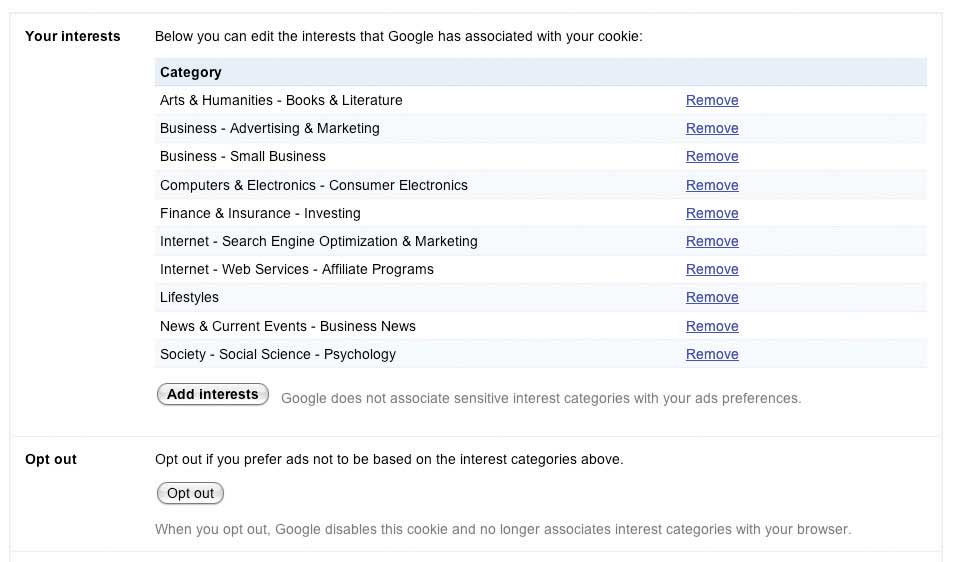

Figure 8.17 Here’s an example of one user’s interests, as tracked by Google’s “Interest-based Ads” and displayed in the firm’s “Ad Preferences Manager.”

Google has also placed significant control in the hands of users, with options at program launch that were notably more robust than those of its competitors.Hansell, 2009. Each interest-based ad is accompanied by an “Ads by Google” link that will bring users to a page describing Google advertising and which provides access to the company’s “Ads Preferences Manager.” This tool allows surfers to see any of the hundreds of potential categorizations that Google has assigned to that browser’s tracking cookie. Users can remove categorizations, and even add interests if they want to improve ad targeting. Some topics are too sensitive to track, and the technology avoids profiling race, religion, sexual orientation, health, political or trade union affiliation, and certain financial categories.R. Mitchell, “What Google Knows about You,” Computerworld, May 11, 2009.

Google also allows users to install a cookie that opts them out of interest-based tracking. And since browser cookies can expire or be deleted, the firm has gone a step further, offering a browser plug-inA small computer program that extends the feature set or capabilities of another application. that will remain permanent, even if a user’s opt-outPrograms that enroll all customer by default, but that allow consumers to discontinue participation if they want to. cookie is purged.

Google’s moves are meant to demonstrate transparency in its ad targeting technology, and the firm’s policies may help raise the collective privacy bar for the industry. While privacy advocates have praised Google’s efforts to put more control in the hands of users, many continue to voice concern over what they see as the increasing amount of information that the firm houses.M. Helft, “BITS; Google Lets Users See a Bit of Selves” New York Times, November 9, 2009. For an avid user, Google could conceivably be holding e-mail (Gmail), photos (Picasa), a Web surfing profile (AdSense and DoubleClick), medical records (Google Health), location (Google Latitude), appointments (Google Calendar), transcripts of phone messages (Google Voice), work files (Google Docs), and more.

Google insists that reports portraying it as a data-hording Big Brother are inaccurate. The firm is adamant that user data exists in silos that aren’t federated in any way, nor are employees permitted access to multiple data archives without extensive clearance and monitoring. Data is not sold to third parties. Activities in Gmail, Docs, or most other services isn’t added to targeting profiles. And any targeting is fully disclosed, with users empowered to opt-out at all levels.R. Mitchell, “What Google Knows about You,” Computerworld, May 11, 2009. But critics counter that corporate intensions and data use policies (articulated in a Web site’s Terms of Service) can change over time, and that a firm’s good behavior today is no guarantee of good behavior in the future.R. Mitchell, “What Google Knows about You,” Computerworld, May 11, 2009.

Google does enjoy a lot of user goodwill, and it is widely recognized for its unofficial motto “Don’t Be Evil.” However, some worry that even though Google might not be evil, it could still make a mistake, and that despite its best intensions, a security breach or employee error could leave data dangerously or embarrassingly exposed.

When AOL released search history on over six hundred and fifty thousand of its Web searchers, these log files included queries such as “How to tell your family you’re a victim of incest,” “Surgical help for depression,” “Can you adopt after a suicide attempt,” “Gynecology oncologists in New York City,” “How long will the swelling last after my tummy tuck,” and perhaps most damning, queries that included specific names, addresses, and phone numbers. While AOL offered the data in a way that disguised individual user accounts, in many cases aggregate query detail contained terms so specific, they provided a strong indication of who conducted the searches.D. Kawamoto and E. Mills, “AOL Apologizes for Release of User Search Data,” CNET, August 7, 2006.

While Google has never experienced a blunder of that magnitude, it has suffered minor incidents, including a March 2009 gaffe in which the firm inadvertently shared some Google Docs with contacts who were never granted access to them.J. Kincaid, “Google Privacy Blunder Shares Your Docs without Permission,” TechCrunch, March 7, 2009.

Privacy advocates also worry that the amount of data stored by Google serves as one-stop shopping for litigators and government investigators. The counter argument points to the fact that Google has continually reflected an aggressive defense of data privacy in court cases. When Viacom sued Google over copyright violations in YouTube, the search giant successfully fought the original subpoena, which had requested user-identifying information.R. Mitchell, “What Google Knows about You,” Computerworld, May 11, 2009. And Google was the only one of the four largest search engines to resist a 2006 Justice Department subpoena for search queries.A. Broache, “Judge: Google Must Give Feds Limited Access to Records,” CNET, March 17, 2006.

Google is increasingly finding itself in precedent-setting cases where the law is vague. Google’s Street View, for example, has been the target of legal action in the United States, Canada, Japan, Greece, and the United Kingdom. Varying legal environments create a challenge to the global rollout of any data-driven initiative.L. Sumagaysay, “Not Everyone Likes the (Google Street) View,” Good Morning Silicon Valley, May 20, 2009.

Ad targeting brings to a head issues of opportunity, privacy, security, risk, and legislation. Google is now taking a more active public relations and lobbying role to prevent misperceptions and to be sure its positions are understood. While the field continues to evolve, Google’s experience will lay the groundwork for the future of personalized technology and provide a case study for other firms that need to strike the right balance between utility and privacy. Despite differences, it seems clear to Google, its advocates, and its detractors that with great power comes great responsibility.