From the title of this chapter, you may be wondering—is this chapter going to cover the world? And, in a sense, the answer is yes. When global managers explore how to expand, they start by looking at the world. Knowing the major markets and the stage of development for each allows managers to determine how best to enter and expand. The manager’s goal is to hone in on a new country—hopefully, before their competitors and usually before the popular media does. China and India were expanding rapidly for several years before the financial press, such as the Wall Street Journal, elevated them to their current hot status.

It’s common to find people interested in doing business with a country simply because they’ve read that it’s the new “hot” economy. They may know little or nothing about the market or country—its history, evolution of thought, people, or how interactions are generally managed in a business or social context. Historically, many companies have only looked at new global markets once potential customers or partners have approached them. However, trade barriers are falling, and new opportunities are fast emerging in markets of the Middle East and Africa—further flattening the world for global firms. Companies are increasingly identifying these and other global markets for their products and services and incorporating them into their long-term growth strategies.

Savvy global managers realize that to be effective in a country, they need to know its recent political, economic, and social history. This helps them evaluate not only the current business opportunity but also the risk of political, economic, and social changes that can impact their business. First, Section 4.1 "Classifying World Economies" outlines how businesses and economists evaluate world economies. Then, the remaining sections review what developed and developing worlds are and how they differ, as well as explain how to evaluate the expanding set of emerging-market countries, which started with the BRIC countries (i.e., Brazil, Russia, India, and China) and has now expanded to include twenty-eight countries. Effective global managers need to be able to identify the markets that offer the best opportunities for their products and services. Additionally, managers need to monitor these emerging markets for new local companies that take advantage of business conditions to become global competitors.

India and China are among the world’s fastest-growing economies, contributing nearly 30 percent to global economic growth. Both China and India are not emerging economies—they’re actually “re-emerging,” having spent centuries at the center of trade throughout history: “These two Asian giants, which until 1800 used to make up half the world economy, are not, like Japan and Germany, mere nation states. In terms of size and population, each is a continent—and for all the glittering growth rates, a poor one.”“Contest of the Century,” Economist, August 19, 2010, accessed January 3, 2011, http://www.economist.com/node/16846256.

Both India and China are in fierce competition with each other as well as in their quest to catch up with the major economies in the developed world. Each have particular strengths and competitive advantages that have allowed each of them to weather the recent global financial crisis better than most countries. China’s growth has been mainly investment and export driven, focusing on low-cost manufacturing, with domestic consumption as low as 36 percent of gross domestic product (GDP). On the other hand, India’s growth has been derived mostly from a strong services sector and buoyant domestic consumption. India is also much less dependent on trade than China, relying on external trade for about 20 percent of its GDP versus 56 percent for China. The Chinese economy has doubled every eight years for the last three decades—the fastest rate for a major economy in recorded history. By 2011, China is the world’s second largest economy in the world behind the United States.Gopal Ethiraj, “China Edges Out Japan to Become World’s No. 2 Economy,” Asian Tribune, August 18, 2010, accessed January 7, 2011, http://www.asiantribune.com/news/2010/08/18/china-edges-out-japan-become-world%E2%80%99s-no-2-economy. A recent report by PricewaterhouseCoopers forecasts that China could overtake the US economy as early as 2020.Suzanne Rosselet, “Strengths of China and India to Take Them into League of Developing Countries,” Economic Times, May 7, 2010, accessed January 3, 2011, http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/features/corporate-dossier/Strengths-of-China-and-India-to-take-them-into-league-of-developing-countries/articleshow/5900893.cms.

China is also the first country in the world to have met the poverty-reduction target set in the UN Millennium Development Goals and has had remarkable success in lifting more than 400 million people out of poverty. This contrasts sharply with India, where 456 million people (i.e., 42 percent of the population) still live below the poverty line, as defined by the World Bank at $1.25 a day.Suzanne Rosselet, “Strengths of China and India to Take Them into League of Developing Countries,” Economic Times, May 7, 2010, accessed January 3, 2011, http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/features/corporate-dossier/Strengths-of-China-and-India-to-take-them-into-league-of-developing-countries/articleshow/5900893.cms. Section 4.1 "Classifying World Economies" will review in more detail how we classify countries. China has made greater strides in improving the conditions for its people, as measured by the HDI. All of this contributes to the local business conditions by both developing the skill sets of the workforce as well as expanding the number of middle-class consumers and their disposable incomes.

India has emerged as the fourth-largest market in the world when its GDP is measured on the scale of purchasing power parity. Both economies are increasing their share of world GDP, attracting high levels of foreign investment, and are recovering faster from the global crisis than developed countries. “Each country has achieved this with distinctly different approaches—India with a ‘grow first, build later’ approach versus a ‘top-down, supply driven’ strategy in China.”Suzanne Rosselet, “Strengths of China and India to Take Them into League of Developing Countries,” Economic Times, May 7, 2010, accessed January 3, 2011, http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/features/corporate-dossier/Strengths-of-China-and-India-to-take-them-into-league-of-developing-countries/articleshow/5900893.cms.

The Chinese economy historically outpaces India’s by just about every measure. China’s fast-acting government implements new policies with blinding speed, making India’s fractured political system appear sluggish and chaotic. Beijing’s shiny new airport and wide freeways are models of modern development, contrasting sharply with the sagging infrastructure of New Delhi and Mumbai. And as the global economy emerges from the Great Recession, India once again seems to be playing second fiddle. Pundits around the world laud China’s leadership for its well-devised economic policies during the crisis, which were so effective in restarting economic growth that they helped lift the entire Asian region out of the downturn.Michael Schuman, “India vs. China: Whose Economy Is Better?,” Time, January 28, 2010, accessed January 3, 2011, http://www.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,1957281,00.html.

As recently as the early 1990s, India was as rich, in terms of national income per head. China then hurtled so far ahead that it seemed India could never catch up. But India’s long-term prospects now look stronger. While China is about to see its working-age population shrink, India is enjoying the sort of bulge in manpower which brought sustained booms elsewhere in Asia. It is no longer inconceivable that its growth could outpace China’s for a considerable time. It has the advantage of democracy—at least as a pressure valve for discontent. And India’s army is, in numbers, second only to China’s and America’s…And because India does not threaten the West, it has powerful friends both on its own merits and as a counterweight to China.“Contest of the Century,” Economist, August 19, 2010, accessed January 3, 2011, http://www.economist.com/node/16846256.

India’s domestic economy provides greater cushion from external shocks than China’s. Private domestic consumption accounts for 57 percent of GDP in India compared with only 35 percent in China. India’s confident consumer didn’t let the economy down. Passenger car sales in India in December jumped 40 percent from a year earlier.Michael Schuman, “India vs. China: Whose Economy Is Better?,” Time, January 28, 2010, accessed January 3, 2011, http://www.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,1957281,00.html.

Since 1978, China’s economic growth and reform have dramatically improved the lives of hundreds of millions of Chinese, increased social mobility. The Chinese leadership has reduced the role of ideology in economic policy by adopting a more pragmatic perspective on many political and socioeconomic problems. China’s ongoing economic transformation has had a profound impact not only on China but on the world. The market-oriented reforms China has implemented over the past two decades have unleashed individual initiative and entrepreneurship. The result has been the largest reduction of poverty and one of the fastest increases in income levels ever seen.

China used to be the third-largest economy in the world but has overtaken Japan to become the second-largest in August 2010. It has sustained average economic growth of over 9.5 percent for the past 26 years. In 2009 its $4.814 trillion economy was about one-third the size of the United States economy.“Background Note: China,” Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs, US Department of State, August 5, 2010, accessed January 3, 2011, http://www.state.gov/r/pa/ei/bgn/18902.htm. China leapfrogged over Japan and became the world’s number two economy in the second quarter of 2010, as receding global growth sapped momentum and stunted a shaky recovery.

India’s economic liberalization in 1991 opened gates to businesses worldwide. In the mid- to late 1980s, Rajiv Gandhi’s government eased restrictions on capacity expansion, removed price controls, and reduced corporate taxes. While his government viewed liberalizing the economy as a positive step, political pressures slowed the implementation of policies. The early reforms increased the rate of growth but also led to high fiscal deficits and a worsening current account. India’s major trading partner then, the Soviet Union, collapsed. In addition, the first Gulf War in 1991 caused oil prices to increase, which in turn led to a major balance-of-payments crisis for India. To be able to cope with these problems, the newly elected Prime Minister Narasimha Rao along with Finance Minister Manmohan Singh initiated a widespread economic liberalization in 1991 that is widely credited with what has led to the Indian economic engine of today. Focusing on the barriers for private sector investment and growth, the reforms enabled faster approvals and began to dismantle the License Raj, a term dating back to India’s colonial historical administrative legacy from the British and referring to a complex system of regulations governing Indian businesses.“Economic History of India,” History of India, accessed January 7, 2011, http://www.indohistory.com/economic_history_of_india.html.

Since 1990, India has been emerging as one of the wealthiest economies in the developing world. Its economic progress has been accompanied by increases in life expectancy, literacy rates, and food security. Goldman Sachs predicts that India’s GDP in current prices will overtake France and Italy by 2020; Germany, the United Kingdom, and Russia by 2025; and Japan by 2035 to become the third-largest economy of the world after the United States and China. India was cruising at 9.4 percent growth rate until the financial crisis of 2008–9, which affected countries the world over.Mamta Badkar, “Race of the Century: Is India or China the Next Economic Superpower?,” Business Insider, February 5, 2011, accessed May 18, 2011, http://www.businessinsider.com/are-you-betting-on-china-or-india-2011-1?op=1.

Both India and China have several strengths and weaknesses that contribute to the competitive battleground between them.

China’s Strengths

India’s Strengths

Infosys is one of India’s new wave of world-class IT companies.

Image courtesy of Infosys.

Each country has embraced the trend toward urbanization differently. Global businesses are impacted in the way cities are run:

China is in much better shape than India is. While India has barely paid attention to its urban transformation, China has developed a set of internally consistent practices across every element of the urbanization operating model: funding, governance, planning, sectorial policies, and shape. India has underinvested in its cities; China has invested ahead of demand and given its cities the freedom to raise substantial investment resources by monetizing land assets and retaining a 25 percent share of value-added taxes. While India spends $17 per capita in capital investments in urban infrastructure annually, China spends $116. Indian cities have devolved little real power and accountability to its cities; but China’s major cities enjoy the same status as provinces and have powerful and empowered political appointees as mayors. While India’s urban planning system has failed to address competing demands for space, China has a mature urban planning regime that emphasizes the systematic development of run-down areas consistent with long-range plans for land use, housing, and transportation.Richard Dobbs and Shirish Sankhe, “Opinion: China vs. India,” Financial Times, May 18, 2010, reprinted on McKinsey Global Institute website, accessed January 3, 2011, http://www.mckinsey.com/mgi/mginews/opinion_china_vs_india.asp.

Despite the urbanization challenges, India is likely to benefit in the future from its younger demographics: “By 2025, nearly 28 percent of China’s population will be aged 55 or older compared with only 16 percent in India.”Richard Dobbs and Shirish Sankhe, “Opinion: China vs. India,” Financial Times, May 18, 2010, reprinted on McKinsey Global Institute website, accessed January 3, 2011, http://www.mckinsey.com/mgi/mginews/opinion_china_vs_india.asp. The trend toward urbanization is evident in both countries. By 2025, 64 percent of China’s population will be living in urban areas, and 37 percent of India’s people will be living in cities.Richard Dobbs and Shirish Sankhe, “Opinion: China vs. India,” Financial Times, May 18, 2010, reprinted on McKinsey Global Institute website, accessed January 3, 2011, http://www.mckinsey.com/mgi/mginews/opinion_china_vs_india.asp. This historically unique trend offers global businesses exciting markets.

So what markets are likely to benefit the most from these trends? In India, by 2025, the largest markets will be transportation and communication, food, and health care followed by housing and utilities, recreation, and education. Even India’s slower-growing spending categories will represent significant opportunities for businesses because these markets will still be growing rapidly in comparison with their counterparts in other parts of the world. In China’s cities today, the fastest-growing categories are likely to be transportation and communication, housing and utilities, personal products, health care, and recreation and education. In addition, in both China and India, urban infrastructure markets will be massive.Richard Dobbs and Shirish Sankhe, “Opinion: China vs. India,” Financial Times, May 18, 2010, reprinted on McKinsey Global Institute website, accessed January 3, 2011, http://www.mckinsey.com/mgi/mginews/opinion_china_vs_india.asp.

While both India and China have unique strengths as well as many similarities, it’s clear that both countries will continue to grow in the coming decades offering global businesses exciting new domestic markets.See also “India’s Surprising Economic Miracle,” Economist, September 30, 2010, accessed January 3, 2011, http://www.economist.com/node/17147648; “A Bumpier but Freer Road,” Economist, September 3, 2010, accessed January 3, 2011, http://www.economist.com/node/17145035; Chris Monasterski, “Education: India vs. China,” Private Sector Development Blog, World Bank, April 25, 2007, accessed January 7, 2011, http://psdblog.worldbank.org/psdblog/2007/04/education_india.html; Shreyasi Singh, “India vs. China,” The Diplomat, August 27, 2010, accessed January 7, 2011, http://the-diplomat.com/indian-decade/2010/08/27/india-vs-china; “The India vs. China Debate: One Up for India?,” Benzinga, January 29, 2010, accessed January 7, 2011, http://www.benzinga.com/global/104829/the-india-vs-china-debate-one-up-for-india; Steve Hamm, “India’s Advantages over China,” Bloomberg Business, March 6, 2007, accessed January 7, 2011, http://www.businessweek.com/globalbiz/blog/globespotting/archives/2007/03/indias_advantag.html.

(AACSB: Ethical Reasoning, Multiculturalism, Reflective Thinking, Analytical Skills)

Experts debate exactly how to define the level of economic development of a country—which criteria to use and, therefore, which countries are truly developed. This debate crosses political, economic, and social arguments.

When evaluating a country, a manager is assessing the country’s income and the purchasing power of its people; the legal, regulatory, and commercial infrastructure, including communication, transportation, and energy; and the overall sophistication of the business environment.

Why does a country’s stage of development matter? Well, if you’re selling high-end luxury items, for example, you’ll want to focus on the per capita income of the local citizens. Can they afford a $1,000 designer handbag, a luxury car, or cutting-edge, high-tech gadgets? If so, how many people can afford these expensive items (i.e., how large is the domestic market)? For example, in January 2011, the Financial Times quotes Jim O’Neill, a leading business economist, who states, “South Africa currently accounts for 0.6 percent of world GDP. South Africa can be successful, but it won’t be big.”Jennifer Hughes, “‘Bric’ Creator Adds Newcomers to List,” Financial Times, January 16, 2010, accessed January 7, 2011, http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/f717c8e8-21be-11e0-9e3b-00144feab49a.html#ixzz1MKbbO8ET. Section 4.4 "Emerging Markets" discusses the debate around the term emerging markets and which countries should be labeled as such. But clearly the size of the local market is an important key factor for businesspeople.

Even in developing countries, there are always wealthy people who want and can afford luxury items. But these consumers are just as likely to head to the developed world to make their purchase and have little concern about any duties or taxes they may have to pay when bringing the items back into their home country. This is one reason why companies pay special attention to understanding their global consumers as well as where and how these consumers purchase goods. Global managers also focus on understanding if a country’s target market is growing and by what rate. Countries like China and India caught the attention of global companies, because they had large populations that were eager for foreign goods and services but couldn’t afford them. As more people in each country acquired wealth, their buying appetites increased. The challenge is how to identify which consumers in which countries are likely to become new customers. Managers focus on globally standard statistics as one set of criteria to understand the stage of development of any country that they’re exploring for business.“Global Economies,” CultureQuest Global Business Multimedia Series (New York: Atma Global, 2010).

Let’s look more closely at some of these globally standard statistics and classifications that are commonly used to define the stage of a country’s development.

Gross domestic product (GDP)The value of all the goods and services produced by a country in a single year. is the value of all the goods and services produced by a country in a single year. Usually quoted in US dollars, the number is an official accounting of the country’s output of goods and services. For example, if a country has a large black, or underground, market for transactions, it will not be included in the official GDP. Emerging-market countries, such as India and Russia, historically have had large black-market transactions for varying reasons, which often meant their GDP was underestimated.

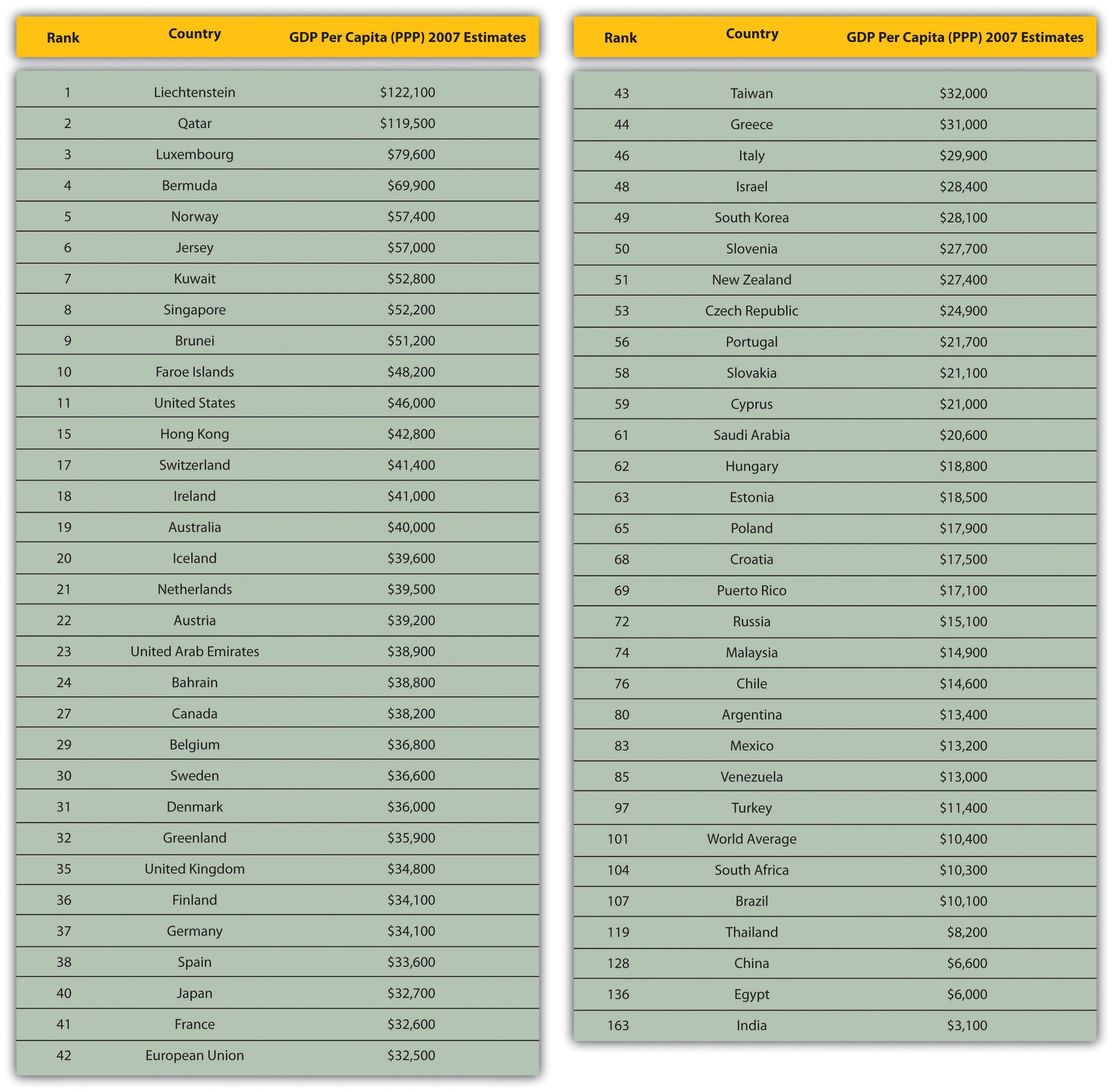

Figure 4.1

Source: US Central Intelligence Agency, “Country Comparison: GDP (PPP),” World Factbook, accessed June 3, 2011, https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2001rank.html.

Figure 4.1 shows the total size of the economy, but a company will want to know the income per person, which may be a better indicator of the strength of the local economy and the market opportunity for a new consumer product. GDP is often quoted on a per person basis. Per capita GDPThe value of the GDP divided by the population of the country. This is also referred to as the nominal per capita GDP. is simply the GDP divided by the population of the country.

The per capita GDP can be misleading because actual costs in each country differ. As a result, more managers rely on the GDP per personThe value of the GDP adjusted for purchasing power; helps managers understand how much income local residents have. adjusted for purchasing power to understand how much income local residents have. This number helps professionals evaluate what consumers in the local market can afford.

Companies selling expensive goods and services may be less interested in economies with low per capita GDP. Figure 4.2 "Per Capita GDP on a Purchasing Power Parity Basis" shows the income (GDP) on a per person basis. For space, the chart has been condensed by removing lower profile countries, but the ranks are valid. Surprisingly, some of the hottest emerging-market countries—China, India, Turkey, Brazil, South Africa, and Mexico—rank very low on the income per person charts. So, why are these markets so exciting? One reason might be that companies selling cheaper, daily-use items, such as soap, shampoos, and low-end cosmetics, have found success entering developing, but promising, markets.

Figure 4.2 Per Capita GDP on a Purchasing Power Parity Basis

Source: US Central Intelligence Agency, “Country Comparison: GDP—Per Capita (PPP),” World Factbook, accessed June 3, 2011, https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2004rank.html.

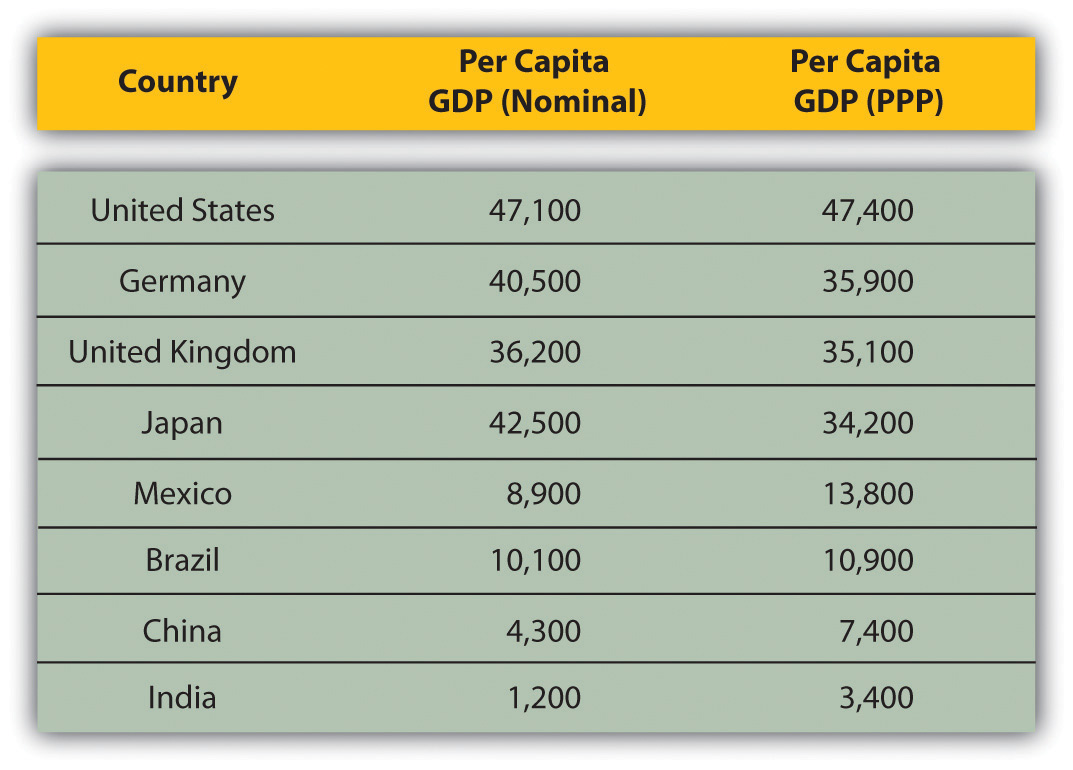

To compare production and income across countries, we need to look at more than just GDP. Economists seek to adjust this number to reflect the different costs of living in specific countries. Purchasing power parity (PPP)An economic theory that adjusts the exchange rate between countries to ensure that a good is purchased for the same price in the same currency. is, in essence, an economic theory that adjusts the exchange rate between countries to ensure that a good is purchased for the same price in the same currency. For example, a basic cup of coffee should cost the same in London as in New York.

A nation’s GDP at purchasing power parity (PPP) exchange rates is the sum value of all goods and services produced in the country valued at prices prevailing in the United States. This is the measure most economists prefer when looking at per-capita welfare and when comparing living conditions or use of resources across countries. The measure is difficult to compute, as a US dollar value has to be assigned to all goods and services in the country regardless of whether these goods and services have a direct equivalent in the United States (for example, the value of an ox-cart or non-US military equipment); as a result, PPP estimates for some countries are based on a small and sometimes different set of goods and services. In addition, many countries do not formally participate in the World Bank’s PPP project to calculate these measures, so the resulting GDP estimates for these countries may lack precision. For many developing countries, PPP-based GDP measures are multiples of the official exchange rate (OER) measure. The differences between the OER- and PPP-denominated GDP values for most of the wealthy industrialized countries are generally much smaller.US Central Intelligence Agency, “Country Comparison:GDP (PPP),” World Factbook, accessed January 3, 2011, https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2001rank.html.

In some countries, like Germany, the United Kingdom, or Japan, the cost of living is quite high and the per capita GDP (nominal) is higher than the GDP adjusted for purchasing power. Conversely, in countries like Mexico, Brazil, China, and India, the per capita GDP adjusted for purchasing power is higher than the nominal per capita GDP, implying that local consumers in each country can afford more with their incomes.

Figure 4.3 Per Capita GDP (Nominal) versus Per Capita GDP (PPP) of Select Countries (2010)

Sources: “List of Countries by GDP (Nominal) Per Capita,” Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_GDP_(nominal)_per_capita. “Country Comparison: GDP—Per Capita (PPP),” US Central Intelligence Agency, https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2004rank.html.

GDP and purchasing power provide indications of a country’s level of economic development by using an income-focused statistic. However, in recent years, economists and business analysts have focused on indicators that measure whether people’s needs are satisfied and whether the needs are equally met across the local population. One such indication is the human development index (HDI)A summary composite index that measures a country’s average achievements in three basic aspects of human development: health, knowledge, and a decent standard of living., which measures people’s satisfaction in three key areas—long and healthy life in terms of life expectancy; access to quality education equally; and a decent, livable standard of living in the form of income.

Since 1990, the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) has produced an annual report listing the HDI for countries. The HDI is a summary composite index that measures a country’s average achievements in three basic aspects of human development: health, knowledge, and a decent standard of living. Health is measured by life expectancy at birth; knowledge is measured by a combination of the adult literacy rate and the combined primary, secondary, and tertiary gross enrollment ratio; and standard of living by (income as measured by) GDP per capita (PPP US$).UNDP, “Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) about the Human Development Index (HDI): What Is the HDI?,” Human Development Reports, accessed May 15, 2011, http://hdr.undp.org/en/statistics/hdi.

While the HDI is not a complete indicator of a country’s level of development, it does help provide a more comprehensive picture than just looking at the GDP. The HDI, for example, does not reflect political participation or gender inequalities. The HDI and the other composite indices can only offer a broad proxy on some of the key the issues of human development, gender disparity, and human poverty.UNDP, “Is the HDI Enough to Measure a Country’s Level of Development?,” Human Development Reports, accessed May 15, 2011, http://hdr.undp.org/en/statistics/hdi. Table 4.1 "Human Development Index (HDI)—2010 Rankings" shows the rankings of the world’s countries for the HDI for 2010 rankings. Measures such as the HDI and its components allow global managers to more accurately gauge the local market.

Table 4.1 Human Development Index (HDI)—2010 Rankings

| Very High Human Development | High Human Development | Medium Human Development | Low Human Development |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Norway | 43. Bahamas | 86. Fiji | 128. Kenya |

| 2. Australia | 44. Lithuania | 87. Turkmenistan | 129. Bangladesh |

| 3. New Zealand | 45. Chile | 88. Dominican Republic | 130. Ghana |

| 4. United States | 46. Argentina | 89. China | 131. Cameroon |

| 5. Ireland | 47. Kuwait | 90. El Salvador | 132. Myanmar |

| 6. Liechtenstein | 48. Latvia | 91. Sri Lanka | 133. Yemen |

| 7. Netherlands | 49. Montenegro | 92. Thailand | 134. Benin |

| 8. Canada | 50. Romania | 93. Gabon | 135. Madagascar |

| 9. Sweden | 51. Croatia | 94. Suriname | 136. Mauritania |

| 10. Germany | 52. Uruguay | 95. Bolivia (Plurinational State of) | 137. Papua New Guinea |

| 11. Japan | 53. Libyan Arab Jamahiriya | 96. Paraguay | 138. Nepal |

| 12. Korea (Republic of) | 54. Panama | 97. The Philippines | 139. Togo |

| 13. Switzerland | 55. Saudi Arabia | 98. Botswana | 140. Comoros |

| 14. France | 56. Mexico | 99. Moldova (Republic of) | 141. Lesotho |

| 15. Israel | 57. Malaysia | 100. Mongolia | 142. Nigeria |

| 16. Finland | 58. Bulgaria | 101. Egypt | 143. Uganda |

| 17. Iceland | 59. Trinidad and Tobago | 102. Uzbekistan | 144. Senegal |

| 18. Belgium | 60. Serbia | 103. Micronesia (Federated States of) | 145. Haiti |

| 19. Denmark | 61. Belarus | 104. Guyana | 146. Angola |

| 20. Spain | 62. Costa Rica | 105. Namibia | 147. Djibouti |

| 21. Hong Kong, China (SAR) | 63. Peru | 106. Honduras | 148. Tanzania (United Republic of) |

| 22. Greece | 64. Albania | 107. Maldives | 149. Côte d'Ivoire |

| 23. Italy | 65. Russian Federation | 108. Indonesia | 150. Zambia |

| 24. Luxembourg | 66. Kazakhstan | 109. Kyrgyzstan | 151. Gambia |

| 25. Austria | 67. Azerbaijan | 110. South Africa | 152. Rwanda |

| 26. United Kingdom | 68. Bosnia and Herzegovina | 111. Syrian Arab Republic | 153. Malawi |

| 27. Singapore | 69. Ukraine | 112. Tajikistan | 154. Sudan |

| 28. Czech Republic | 70. Iran (Islamic Republic of) | 113. Vietnam | 155. Afghanistan |

| 29. Slovenia | 71. The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia | 114. Morocco | 156. Guinea |

| 30. Andorra | 72. Mauritius | 115. Nicaragua | 157. Ethiopia |

| 31. Slovakia | 73. Brazil | 116. Guatemala | 158. Sierra Leone |

| 32. United Arab Emirates | 74. Georgia | 117. Equatorial Guinea | 159. Central African Republic |

| 33. Malta | 75. Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic of) | 118. Cape Verde | 160. Mali |

| 34. Estonia | 76. Armenia | 119. India | 161. Burkina Faso |

| 35. Cyprus | 77. Ecuador | 120. Timor-Leste | 162. Liberia |

| 36. Hungary | 78. Belize | 121. Swaziland | 163. Chad |

| 37. Brunei Darussalam | 79. Colombia | 122. Lao People's Democratic Republic | 164. Guinea-Bissau |

| 38. Qatar | 80. Jamaica | 123. Solomon Islands | 165. Mozambique |

| 39. Bahrain | 81. Tunisia | 124. Cambodia | 166. Burundi |

| 40. Portugal | 82. Jordan | 125. Pakistan | 167. Niger |

| 41. Poland | 83. Turkey | 126. Congo | 168. Congo (Democratic Republic of the) |

| 42. Barbados |

84. Algeria 85. Tonga |

127. São Tomé and Príncipe | 169. Zimbabwe |

Source: UNDP, “Human Development Index (HDI)—2010 Rankings,” Human Development Reports, accessed January 6, 2011, http://hdr.undp.org/en/statistics.

In 1995, the UNDP introduced two new measures of human development that highlight the status of women in each society.

The first, gender-related development index (GDI), measures achievement in the same basic capabilities as the HDI does, but takes note of inequality in achievement between women and men. The methodology used imposes a penalty for inequality, such that the GDI falls when the achievement levels of both women and men in a country go down or when the disparity between their achievements increases. The greater the gender disparity in basic capabilities, the lower a country’s GDI compared with its HDI. The GDI is simply the HDI discounted, or adjusted downwards, for gender inequality.

The second measure, gender empowerment measure (GEM), is a measure of agency. It evaluates progress in advancing women’s standing in political and economic forums. It examines the extent to which women and men are able to actively participate in economic and political life and take part in decision making. While the GDI focuses on expansion of capabilities, the GEM is concerned with the use of those capabilities to take advantage of the opportunities of life.UNDP, “Measuring Inequality: Gender-related Development Index (GDI) and Gender Empowerment Measure (GEM),” Human Development Reports, accessed January 3, 2011, http://hdr.undp.org/en/statistics/indices/gdi_gem.

In 1997, UNDP added a further measure—the human poverty index (HPI)A composite index that uses indicators of the most basic dimensions of deprivation: a short life (i.e., longevity), lack of basic education (i.e., knowledge), and lack of access to public and private resources (i.e., decent standard of living)..

If human development is about enlarging choices, poverty means that opportunities and choices most basic to human development are denied. Thus a person is not free to lead a long, healthy, and creative life and is denied access to a decent standard of living, freedom, dignity, self-respect and the respect of others. From a human development perspective, poverty means more than the lack of what is necessary for material well-being.

For policy-makers, the poverty of choices and opportunities is often more relevant than the poverty of income. The poverty of choices focuses on the causes of poverty and leads directly to strategies of empowerment and other actions to enhance opportunities for everyone. Recognizing the poverty of choices and opportunities implies that poverty must be addressed in all its dimensions, not income alone.UNDP, “The Human Poverty Index (HPI),” Human Development Reports, accessed January 3, 2011, http://hdr.undp.org/en/statistics/indices/hpi.

Rather than measure poverty by income, the HPI is a composite index that uses indicators of the most basic dimensions of deprivation: a short life (longevity), a lack of basic education (knowledge), and a lack of access to public and private resources (decent standard of living). There are two different HPIs—one for developing countries (HPI-1) and another for a group of select high-income OECD (Organization for Economic and Development) countries (HPI-2), which better reflects the socioeconomic differences between the two groups. HPI-2 also includes a fourth indicator that measures social exclusion as represented by the rate of long-term unemployment.UNDP, “The Human Poverty Index (HPI),” Human Development Reports, accessed January 3, 2011, http://hdr.undp.org/en/statistics/indices/hpi.

So, the richest countries—like Liechtenstein, Qatar, and Luxembourg—may not always have big local markets or, in contrast, the poorest countries may have the largest local market as determined by the size of the local population. Savvy business managers need to compare and contrast a number of different classifications, statistics, and indicators before they can interpret the strength, depth, and extent of a local market opportunity for their particular industry and company.

The goal of this chapter is to review a sampling of countries in the developed, developing, and emerging markets to understand how economists and businesspeople perceive market opportunities. Of course, one chapter can’t do justice to all of these markets, but through select examples, you’ll see how countries have evolved in the post–World War II global economic, political, and social environments. Remember that the goal of any successful businessperson is to monitor the changing markets and spot opportunities and trends ahead of his or her peers.

The major classifications used by analysts are evolving. The primary criteria for determining the stage of development may change within a decade as demonstrated with the addition of the gender and poverty indices. In addition, with every global crisis or event, there’s a tendency to add more acronyms and statistics into the mix. Savvy global managers have to sort through these to determine what’s relevant to their industry and their business objectives in one or more countries. For example, in the fall of 2010, after two years of global financial crisis, global investors started using a new acronym to describe the changing economic fortunes among countries: HIICs, or heavily indebted industrialized countries. These countries include the United States, the United Kingdom, and Japan. “‘Developed markets are basically behaving like emerging markets,’ says HSBC’s Richard Yetsenga. ‘And emerging markets are quickly becoming more developed.’”Kelly Evans, “‘HIIC’ Nations Are Acting Like Backwaters,” Wall Street Journal, October 1, 2010, accessed January 3, 2011, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748704789404575524402059410506.html. Investors are pulling money from the developed countries and into the BRIC countries (i.e., Brazil, Russia, India, and China), which are “‘where the population growth is, where the raw materials are, and where the economic growth is,’ says Michael Penn, global equity strategist at Bank of America Merrill Lynch.”Kelly Evans, “‘HIIC’ Nations Are Acting Like Backwaters,” Wall Street Journal, October 1, 2010, accessed January 3, 2011, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748704789404575524402059410506.html. The key here is to understand that classifications—just like countries and international business—are constantly evolving.

Rather than being overwhelmed by the evolving data, it’s critical to understand why the changes are occurring, what attitudes and perceptions are shifting, and if they are supported by real, verifiable data. In the above example of HIICs, investors from the major economies are likely motivated by quick gains on stock prices and the prevailing perception that emerging markets offer companies the best growth prospects. But as a businessperson, the timeline for your company would be in years, not months; so it’s important to evaluate information based on your company’s goals rather than relying on the media, investment markets, or other singularly focused industry professionals.

To truly monitor the global business arena and select prospective countries, you need to follow the news, trends, and available information for a period of time. Over time, savvy global managers develop a geographic, industrial, or product expertise—or some combination. Those who become experts on a specific country spend a great deal of time in the country, sometimes learn the language, and almost always develop an understanding of the country’s political, economic, and social history as well as its culture and evolution. They gain a deeper knowledge of more than just the country’s current business environment. In the business world, these folks are affectionately called “old hands”—as in he is an “old China hand” or an “old Indonesia hand.” This is a reflection of how seasoned or experienced a person is with a country.

(AACSB: Reflective Thinking, Analytical Skills)

Many people are quick to focus on the developing economies and emerging markets as offering the brightest growth prospects. And indeed, this is often the case. However, you shouldn’t overlook the developed economies; they too can offer growth opportunities, depending on the specific product or service. The key is to understand what developed economies are and to determine their suitability for a company’s strategy.

In essence, developed economiesAlso known as advanced economies, these countries are characterized as postindustrial with high per capita incomes, competitive industries, transparent legal and regulatory environments, and well-developed commercial infrastructures., also known as advanced economies, are characterized as postindustrial countries—typically with a high per capita income, competitive industries, transparent legal and regulatory environments, and well-developed commercial infrastructure. Developed countries also tend to have high human development index (HDI) rankings—long life expectancies, high-quality health care, equal access to education, and high incomes. In addition, these countries often have democratically elected governments.

In general, the developed world encompasses Canada, the United States, Western Europe, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand. While these economies have moved from a manufacturing focus to a service orientation, they still have a solid manufacturing base. However, just because an economy is developed doesn’t mean that it’s among the largest economies. And, conversely, some of the world’s largest economies—while growing rapidly—don’t have competitive industries or transparent legal and regulatory environments. The infrastructure in these countries, while improving, isn’t yet consistent or substantial enough to handle the full base of business and consumer demand. Countries like Brazil, Russia, India, and China—also known as BRIC—are hot emerging markets but are not yet considered developed by most widely accepted definitions. Section 4.4 "Emerging Markets" covers the BRIC countries and other emerging markets.

The following sections contain a sampling of the largest developed countries that focuses on the business culture, economic environment, and economic structure of each country.The sections that follow are excerpted in part from two resources owned by author Sanjyot P. Dunung’s firm, Atma Global: CultureQuest Business Multimedia Series and bWise: Business Wisdom Worldwide. The excerpts are reprinted with permission and attributed to the country-specific product when appropriate.

Geographically, the United States is the fourth-largest country in the world—after Russia, China, and Canada. It sits in the middle of North America, bordered to the north by Canada and to the south by Mexico. With a history steeped in democratic and capitalist institutions, values and entrepreneurship, the United States has been the driver of the global economy since World War II.

The US economy accounts for nearly 25 percent of the global gross domestic product (GDP). Recently, the severe economic crisis and recession have led to double-digit unemployment and record deficits. Nevertheless, the United States remains a global economic engine, with an economy that is about twice as large as that of the next single country, China. With an annual GDP of more than $14 trillion, only the entire European Union can match the US economy in size. An economist’s proverb notes that when the US economy sneezes, the rest of the world catches a cold. Despite its massive wealth, 12 percent of the population lives below the poverty line.US Central Intelligence Agency, “North America: United States: Economy,” World Factbook, accessed January 7, 2011, https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/us.html.

Throughout the cycles of growth and contractions, the US economy has a history of bouncing back relatively quickly. In recessions, the government and the business community tend to respond swiftly with measures to reduce costs and encourage growth. Americans often speak in terms of bull and bear markets. A bull marketA market in which prices rise for a prolonged period of time. is one in which prices rise for a prolonged period of time, while a bear marketA market in which prices steadily drop in a downward cycle. is one in which prices steadily drop in a downward cycle.

The strength of the US economy is due in large part to its diversity. Today, the United States has a service-based economy. In 2009, industry accounted for 21.9 percent of the GDP; services (including finance, insurance, and real estate) for 76.9 percent; and agriculture for 1.2 percent.US Central Intelligence Agency, “North America: United States: Economy,” World Factbook, accessed January 7, 2011, https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/us.html. Manufacturing is a smaller component of the economy; however, the United States remains a major global manufacturer. The largest manufacturing sectors are highly diversified and technologically advanced—petroleum, steel, motor vehicles, aerospace, telecommunications, chemicals, electronics, food processing, consumer goods, lumber, and mining.

The sectors that have grown the most in the past decades are financial services, car manufacturing, and, most important, information technology (IT), which has more than doubled its output in the past decade. It now accounts for nearly 10 percent of the country’s GDP. As impressive as that figure is, it hardly takes into account the many ways in which IT has transformed the US economy. After all, improvements in information technology and telecommunications have increased the productivity of nearly every sector of the economy.

The United States is so big that its abundant natural resources account for only 4.3 percent of its GDP. Even so, it has the largest agricultural base in the world and is among the world’s leading producers of petroleum and timber products. US farms produce about half the world’s corn—though most of it is grown to feed beef and dairy cattle. The US imports about 30 percent of its oil, despite its own massive reserves. That’s because Americans consume roughly a quarter of the world’s total energy and more than half its oil, making them dependent on other oil-producing nations in some fairly troublesome ways.

The US retail and entertainment industries are very valuable to the economy. The country’s media products, including movies and music, are the country’s most visible exports. When it comes to business, the United States might well be called the “king of the jungle.” Emboldened by a strong free-market economy, legions of US companies have achieved unparalleled success. One by-product of this competitive spirit is an abundance of secure, well-managed business partnerships at home and abroad. And although the majority of US companies aren’t multinational giants, an emphasis on hard work and a sense of fair play pervade the business culture.

In a culture where entrepreneurialism is practically a national religion, the business landscape is broad and diverse. At one end are enduring multinationals, like Coca-Cola and General Electric, which were founded by visionary entrepreneurs and are now run by boards of directors and appointed managers who answer to shareholders. At the other end of the spectrum are small businesses—millions of them—many owned and operated by a single person.

Today, more companies than ever are “going global,” fueled by an increased demand for varied products and services around the world. Expanding into new markets overseas—often through joint ventures and partnerships—is becoming a requirement for success in business.

Another trend that has gained much media attention is outsourcing—subcontracting work, sometimes to foreign companies. It’s now quite common for companies of all sizes to pay outside firms to do their payroll, provide telecommunications support, and perform a range of operational services. This has led to a growth in small contractors, often operating out of their homes, who offer a variety of services, including advertising, public relations, and graphic design.CultureQuest Business Multimedia Series: USA (New York: Atma Global, 2010); bWise: Business Wisdom Worldwide: USA (New York: Atma Global, 2011).

Today, the European Union (EU) represents the monetary union of twenty-seven European countries. (Chapter 5 "Global and Regional Economic Cooperation and Integration", Section 5.2 "Regional Economic Integration" reviews the history of the EU and the factors impacting its outlook.) One of the primary purposes of the EU was to create a single market for business and workers accompanied by a single currency, the euro. Internally, the EU has made strides toward abolishing trade barriers, has adopted a common currency, and is striving toward convergence of living standards. Internationally, the EU aims to bolster Europe’s trade position and its political and economic power. Because of the great differences in per capita income among member states (i.e., from $7,000 to $79,000) and historic national animosities, the EU faces difficulties in devising and enforcing common policies. The EU’s strengths also come from the formidable strengths of some of its economic powerhouse members. Germany is the leading economy in the EU.

Germany has the fifth-largest economy in the world, after the United States, China, Japan, and India. With a heavily export-oriented economy, the country is a leading exporter of machinery, vehicles, chemicals, and household equipment and benefits from a highly skilled labor force. It remains the largest and strongest economy in Europe and the second most-populous country after Russia in Europe.

The country has a socially responsible market economy that encourages competition and free initiative for the individual and for business. The Grundgesetz (Basic Law) guarantees private enterprise and private property, but stipulates that these rights must be exercised in the welfare and interest of the public.

Germany’s economic development has been shaped, in large part, by its lack of natural resources, making it highly dependent on other countries. This may explain why the country has repeatedly sought to expand its power, particularly on its eastern flank.

Since the end of World War II, successive governments have sought to retain the basic elements of Germany’s complex economic system (the Soziale Marktwirtschaft). Notably, relationships between employer and employee and between private industry and government have remained stable. Over the years, the country has had few industrial disputes. Furthermore, active participation by all groups in the economic decision making process has ensured a level of cooperation unknown in many other Western countries. Nevertheless, high unemployment and high fiscal deficits are key issues.

Overall, living standards are high, and Germany is a prosperous nation. The majority of Germans live in comfortable housing with modern amenities. The choice of available food is broad and includes cuisine from around the world. Germans enjoy luxury cars, and technology and fashion are big industries. Under federal law, workers are guaranteed minimum income, vacation time, and other benefits. Recently, the government has focused on economic reforms, particularly in the labor market, and tax reduction.

Germany is home to some of the world’s most important businesses and industries. Daimler, Volkswagen, and BMW are global forces in the automotive field. Germany remains the fourth-largest auto manufacturer behind China, Japan, and the United States. German BASF, Hoechst, and Bayer are giants in the chemical industry. Siemens, a world leader in electronics, is the country’s largest employer, while Bertelsmann is the largest publishing group in the world. In the banking industry, Deutsche Bank is one of the world’s largest. In addition to these international giants, Germany has many small- and medium-sized, highly specialized firms. These businesses make up a disproportionately large part of Germany’s exports.

Services drive the economy, representing 72.3 percent (in 2009) of the total GDP. Industry accounts for 26.8 percent of the economy, and agriculture represents 0.9 percent. Despite the strong services sector, manufacturing remains one of the most important components of the Germany economy. Key German manufacturing industries are among the world’s largest and most technologically advanced producers of iron, steel, coal, cement, chemicals, machinery, vehicles, machine tools, electronics, food and beverages, shipbuilding, and textiles. Manufacturing provides not only significant sources of revenue but also the know-how that Germany exports around the world.CultureQuest Business Multimedia Series: Germany (New York: Atma Global, 2010); bWise: Business Wisdom Worldwide: Germany (New York: Atma Global, 2011).

Located off the east coast of Asia, the Japanese archipelago consists of four large islands—Honshu, Hokkaido, Kyushu, and Shikoku—and about four thousand small islands, which when combined are equal to the size of California.

The American occupation of Japan following World War II laid the foundation for today’s modern economic and political society. The occupation was intended to demilitarize Japan, to fully democratize the government, and to reform Japanese society and the economy. The Americans revised the then-existing constitution along the lines of the British parliamentary model. The Japanese adopted the new constitution in 1946 as an amendment to their original 1889 constitution. On the whole, American reforms rebuilt Japanese industry and were welcomed by the Japanese. The American occupation ended in 1952, when Japan was declared an independent state.

As Japan became an industrial superpower in the 1950s and 1960s, other countries in Asia and the global superpowers began to expect Japan to participate in international aid and defense programs and in regional industrial-development programs. By the late 1960s, Japan had the third-largest economy in the world. However, Japan was no longer free from foreign influences. In one century, the country had gone from being relatively isolated to being dependent on the rest of the world for its resources with an economy reliant on trade.

In the post–World War II period, Japanese politics have not been characterized by sharp divisions between liberal and conservative elements, which in turn have provided enormous support for big business. The Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), created in 1955 as the result of a merger of two of the country’s biggest political parties, has been in power for most of the postwar period. The LDP, a major proponent of big business, generally supports the conservative viewpoint. The “Iron Triangle,” as it is often called, refers to the tight relationship among Japanese politicians, bureaucrats, and big business leaders.

Until recently, the overwhelming success of the economy overshadowed other policy issues. This is particularly evident with the once powerful Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI). For much of Japan’s modern history, MITI has been responsible for establishing, coordinating, and regulating specific industry policies and targets, as well as having control over foreign trade interests. In 2001, its role was assumed by the newly created METI, the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry.

Japan’s post–World War II success has been the result of a well-crafted economic policy that is closely administered by the government in alliance with large businesses. Prior to World War II, giant corporate holding companies called zaibatsu worked in cooperation with the government to promote specific industries. At one time, the four largest zaibatsu organizations were Mitsui, Mitsubishi, Sumitomo, and Yasuda. Each of the four had significant holdings in the fields of banking, manufacturing, mining, shipping, and foreign marketing. Policies encouraged lifetime employment, employer paternalism, long-term relationships with suppliers, and minimal competition. Lifetime employment continues today, although it’s coming under pressure in the ongoing recession. This policy is often credited as being one of the stabilizing forces enabling Japanese companies to become global powerhouses.Sanjyot P. Dunung, Doing Business in Asia: The Complete Guide, 2nd ed. (New York: Jossey-Bass, 1998).

The zaibatsus were dismantled after World War II, but some of them reemerged as modern-day keiretsu, and many of their policies continue to have an effect on Japan. Keiretsu refers to the intricate web of financial and nonfinancial relationships between companies that virtually links together in a pattern of formal and informal cross-ownership and mutual obligation. The keiretsu nature of Japanese business has made it difficult for foreign companies to penetrate the commercial sector. In response to recent global economic challenges, the government and private businesses have recognized the need to restructure and deregulate parts of the economy, particularly in the financial sector. However, they have been slow to take action, further aggravating a weakened economy.

Japan has very few mineral and energy resources and relies heavily on imports to bring in almost all of its oil, iron ore, lead, wool, and cotton. It’s the world’s largest importer of numerous raw materials including coal, copper, zinc, and lumber. Despite a shortage of arable land, Japan has gone to great lengths to minimize its dependency on imported agricultural products and foodstuffs, such as grains and beef. Agriculture represents 1.6 percent of the economy. The country’s chief crops include rice and other grains, vegetables, and fruits. Japanese political and economic protectionist policies have ensured that the Japanese remain fully self-sufficient in rice production, which is their main staple.

As with other developed nations, services lead the economy, representing 76.5 percent of the national GDP.US Central Intelligence Agency, “East & Southeast Asia: Japan: Economy,” World Factbook, accessed January 4, 2011, https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ja.html. Industry accounts for 21.9 percent of the country’s output. Japan benefits from its highly skilled workforce. However, the high cost of labor combined with the cost of importing raw materials has significantly affected the global competitiveness of its industries. Japan excels in high-tech industries, particularly electronics and computers. Other key industries include automobiles, machinery, and chemicals. The service industry is beginning to expand and provide high-quality computer-related services, advertising, financial services, and other advanced business services.CultureQuest Business Multimedia Series: Japan (New York: Atma Global, 2010); bWise: Business Wisdom Worldwide: Japan (New York: Atma Global, 2011).

(AACSB: Reflective Thinking, Analytical Skills)

The developing worldCountries that rank lower on various classifications including GDP and the HDI. These countries tend to have economies focused on one or more key industries and tend to have poor commercial infrastructure. The local business environment tends not to be transparent, and there is usually a weak competitive industry. refers to countries that rank lower on the various classifications from Section 4.1 "Classifying World Economies". The residents of these economies tend to have lower discretionary income to spend on nonessential goods (i.e., goods beyond food, housing, clothing, and other necessities). Many people, particularly those in developing countries, often find the classifications limiting or judgmental. The intent here is to focus on understanding the information that a global business professional will need to determine whether a country, including a developing country, offers an interesting local market. Some countries may perceive the classification as a slight; others view it as a benefit. For example, in global trade, being a developing country sometimes provides preferences and extra time to meet any requirements dismantling trade barriers.

[In the World Trade Organization (WTO), t]here are no WTO definitions of “developed” and “developing” countries. Members announce for themselves whether they are “developed” or “developing” countries. However, other members can challenge the decision of a member to make use of provisions available to developing countries.

Developing country status in the WTO brings certain rights. There are for example provisions in some WTO Agreements which provide developing countries with longer transition periods before they are required to fully implement the agreement and developing countries can receive technical assistance.

That a WTO member announces itself as a developing country does not automatically mean that it will benefit from the unilateral preference schemes of some of the developed country members such as the Generalized System of Preferences (GSP). In practice, it is the preference giving country which decides the list of developing countries that will benefit from the preferences.“Who Are the Developing Countries in the WTO?,” World Trade Organization, accessed January 5, 2011, http://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/devel_e/d1who_e.htm.

Developing countries sometimes find that their economies improve and gradually they become emerging markets. (Section 4.4 "Emerging Markets" discusses emerging markets.) Many developing economies represent old cultures and rich histories. Focusing only on today’s political, economic, and social conditions distorts the picture of what these countries have been and what they might become again. This category hosts the greatest number of countries around the world.

It’s important to understand that the term developing countries is different from Third-World countries, which was a traditional classification for countries along political and economic lines. It helps to understand how this terminology has evolved.

When people talk about the poorest countries of the world, they often refer to them with the general term Third World, and they think everybody knows what they are talking about. But when you ask them if there is a Third World, what about a Second or a First World, you almost always get an evasive answer…

The use of the terms First, the Second, and the Third World is a rough, and it’s safe to say, outdated model of the geopolitical world from the time of the cold war.

There is no official definition of the first, second, and the third world. Below is OWNO’s [One World—Nations Online] explanation of the terms…

After World War II the world split into two large geopolitical blocs and spheres of influence with contrary views on government and the politically correct society:

1. The bloc of democratic-industrial countries within the American influence sphere, the “First World.”

2. The Eastern bloc of the communist-socialist states, the “Second World.”

3. The remaining three-quarters of the world’s population, states not aligned with either bloc were regarded as the “Third World.”

4. The term “Fourth World,” coined in the early 1970s by Shuswap Chief George Manuel, refers to widely unknown nations (cultural entities) of indigenous peoples, “First Nations” living within or across national state boundaries…

The term “First World” refers to so-called developed, capitalist, industrial countries, roughly, a bloc of countries aligned with the United States after World War II, with more or less common political and economic interests: North America, Western Europe, Japan and Australia.“Worlds within the World?,” One World—Nations Online, accessed January 5, 2011, http://www.nationsonline.org/oneworld/third_world_countries.htm.

Developing economies typically have poor, inadequate, or unequal access to infrastructure. The low personal incomes result in a high degree of poverty, as measured by the human poverty index (HPI) from Section 4.1 "Classifying World Economies". These countries, unlike the developed economies, don’t have mature and competitive industries. Rather, the economies usually rely heavily on one or more key industries—often related to commodities, like oil, minerals mining, or agriculture. Many of the developing countries today are in Africa, parts of Asia, the Middle East, parts of Latin America, and parts of Eastern Europe.

Developing countries can seem like an oxymoron in terms of technology. In daily life, high-tech capabilities in manufacturing coexist alongside antiquated methodologies. Technology has caused an evolution of change in just a decade or two. For example, twenty years ago, a passerby looking at the metal shanties on the sides of the streets of Mumbai, India, or Jakarta, Indonesia, would see abject poverty in terms of the living conditions; today, that same passerby peering inside the small huts would see the flicker of a computer screen and almost all the urban dwellers—in and around the shanties—sporting cell phones. Installing traditional telephone infrastructure was more costly and time-consuming for governments, and consumers opted for the faster and relatively cheaper option of cell phones.

Gillette’s Innovative Razor Sales

Companies find innovative ways to sell to developing world markets. Procter & Gamble (P&G)’s latest innovation is a Gillette-brand eleven-cent blade. “Gillette commands about 70 percent of the world’s razor and blade sales, but it lags behind rivals in India and other developing markets, mainly because those consumers can’t afford to buy its flagship products.”Ellen Byron, “Gillette’s Latest Innovation in Razors: The 11-Cent Blade,” Wall Street Journal, October 1, 2010, accessed January 5, 2011, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748704789404575524273890970954.html. The company has designed a basic blade, called the Gillette Guard, that isn’t available in the United States or other richer economies. The blade is designed for the developing world, with the goal of bringing “‘more consumers into Gillette,’ says Alberto Carvalho, P&G’s vice president of male grooming in emerging markets…Winning over low-income consumers in developing markets is crucial to the growth strategy….The need to grow in emerging markets is pushing P&G to change its product development strategy. In the past, P&G would sell basically the same premium Pampers diapers, Crest toothpaste, or Olay moisturizers in developing countries, where only the wealthiest consumers could afford them.”Ellen Byron, “Gillette’s Latest Innovation in Razors: The 11-Cent Blade,” Wall Street Journal, October 1, 2010, accessed January 5, 2011, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748704789404575524273890970954.html. The company’s approach now is to determine what the consumers can afford in each country and adjust the product features to meet the target price.

Global companies also recognize that in many developing countries, the local government is the buyer—particularly for higher value-added products and services, such as high-tech items, equipment, and infrastructure development. In addition, companies assess the political and economic environment in order to evaluate the risks and opportunities for business in managing key government relationships. (For more information on international trade, see Chapter 2 "International Trade and Foreign Direct Investment", Section 2.1 "What Is International Trade Theory?" and Chapter 2 "International Trade and Foreign Direct Investment", Section 2.2 "Political and Legal Factors That Impact International Trade".) In much of Africa and the Middle East, where the economies rely on one or two key industries, the governments remain heavily involved in sourcing and awarding key contracts. The lack of competitive domestic industry and local transparency has also made these economies ripe for graft.The sections that follow are excerpted in part from two resources owned by author Sanjyot P. Dunung’s firm, Atma Global: CultureQuest Business Multimedia Series and bWise: Business Wisdom Worldwide. The excerpts are reprinted with permission and attributed to the country-specific product when appropriate.

Studies have shown that developing countries that are known to be rich in hydrocarbons [mainly oil] are plagued with corruption and environmental pollution. Paradoxically, most extractive resource-rich developing countries are found in the bottom third of the World Bank’s composite governance indicator rankings. Again, on the Transparency International Corruption Perception Index (CPI), 2007—most of the countries found at the bottom of the table are rich in mineral resources. This is indicative of high prevalence of corruption in these countries.Gilbert Sam, “Ghana’s Oil Find: Benefits and Nightmares,” Daily Guide, April 30, 2009, reprinted on Modern Ghana website, accessed January 5, 2011, http://www.modernghana.com/news/213863/1/ghanas-oil-find-benefits-and-nightmares.html.

The Middle East presents an interesting challenge and opportunity for global businesses. Thanks in large part to the oil-dependent economies, some of these countries are quite wealthy. Figure 4.2 "Per Capita GDP on a Purchasing Power Parity Basis" in Section 4.1 "Classifying World Economies" shows the per capita gross domestic product (GDP) adjusted for purchasing power parity (PPP) for select countries. Interestingly enough Qatar, Kuwait, United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Bahrain all rank in the top twenty-five. Only Saudi Arabia ranks much lower, due mainly to its larger population; however, it still has a per capita GDP (PPP) twice as high as the global average.

While the income level suggests a strong opportunity for global businesses, the inequality of access to goods and services, along with an inadequate and uncompetitive local economy, present both concerns and opportunities. Many of these countries are making efforts to shift from being an oil-dependent economy to a more service-based economy. Dubai, one of the seven emirates in the UAE, has sought to be the premier financial center for the Middle East. The financial crisis of 2008 has temporarily hampered, but not destroyed, these ambitions.

Tucked into the southeastern edge of the Arabian Peninsula, the UAE borders Oman, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia. The UAE is a federation of seven states, called emirates because they are ruled by a local emir. The seven emirates are Abu Dhabi (capital), Dubai, Al-Shāriqah (or Sharjah), Ajmān, Umm al-Qaywayn, Ras’al-Khaymah, and Al-Fujayrah (or Fujairah). Dubai and Abu Dhabi have received the most global attention as commercial, financial, and cultural centers.

Dubai, the Las Vegas of the Middle East

Dubai is sometimes called the Vegas of the Middle East in reference to its glitzy malls, buildings, and consumerism culture. Luxury brands and excessive wealth dominate the culture as oil wealth is displayed brashly. Among other things, Dubai is home to Mall of the Emirates and its indoor alpine ski resort.“About Mall of the Emirates,” Mall of the Emirates, accessed January 5, 2011, http://www.malloftheemirates.com/MOE/En/MainMenu/AboutMOE/tabid/64/Default.aspx. Dubai also features aggressive architectural projects, including the spire-topped Burj Khalifa, which is the tallest skyscraper in the world, and the Palm Islands, which are man-made, palm-shaped, phased land-reclamation developments. Visionary proposals include the world’s first underwater hotel, the Hydropolis. Dubai’s tourism attracts visitors from its more religiously conservative neighbors such as Saudi Arabia as well as from countries in South Asia, primarily for its extensive shopping options. Dubai as well as other parts of the UAE hope to become major global-tourist destinations and have been building hotels, airports, attractions, shops, and infrastructure in order to facilitate this economic diversification goal.

The seven emirates merged in the early 1970s after more than a century of British control of their defense and military affairs. Thanks to its abundant oil reserves, the UAE has grown from an impoverished group of desert states to a wealthy regional commercial and financial center in just thirty years. Its oil reserves are ranked as the world’s seventh-largest and the UAE possesses one of the most-developed economies in West Asia.US Central Intelligence Agency, “Country Comparison: Oil—Proved Reserves,” World Factbook, accessed January 5, 2011, https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2178rank.html. It is the twenty-second-largest economy at market exchange rates and has a high per capita gross domestic product, with a nominal per capita GDP of US$49,995 as per the International Monetary Fund (IMF).“IMF Data Mapper,” International Monetary Fund, accessed January 5, 2011, http://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/index.php. It is the second-largest in purchasing power per capita and has a relatively high human development index (HDI) for the Asian continent, ranking thirty-second globally.UNDP, “Human Development Index (HDI)—2010 Rankings,” Human Development Report 2010: The Real Wealth of Nations and Pathways to Human Development, November 4, 2010, accessed January 5, 2011, http://hdr.undp.org/en/statistics. The UAE is classified as a high-income developing economy by the IMF.Wikipedia, s.v. “United Arab Emirates,” last modified February 15, 2011, accessed February 16, 2011, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_Arab_Emirates.

For more than three decades, oil and global finance drove the UAE’s economy; however, in 2008–9, the confluence of falling oil prices, collapsing real estate prices, and the international banking crisis hit the UAE especially hard.US Central Intelligence Agency, “Middle East: United Arab Emirates,” World Factbook, accessed January 5, 2011, https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ae.html.

Today, the country’s main industries are petroleum and petrochemicals (which account for a sizeable 25 percent of total GDP), fishing, aluminum, cement, fertilizers, commercial ship repair, construction materials, some boat building, handicrafts, and textiles. With the UAE’s intense investment in infrastructure and greening projects, the coastlines have been enhanced with large parks and gardens. Furthermore, the UAE has transformed offshore islands into agricultural projects that produce food.

A key issue for the UAE is the composition of its residents and workforce. The UAE is perhaps one of the few countries in the world where expatriates outnumber the local citizens, or nationals. In fact, of the total population of almost 5 million people, only 20 percent are citizens, and the workforce is composed of individuals from 202 different countries. As a result, the UAE is an incredible melting pot of cultural, linguistic, and religious groups. Migrant workers come mainly from the Indian subcontinent: India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka as well as from Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and other Arab nations. A much smaller number of skilled managers come from Europe, Australia, and North America. While technically the diverse population results in a higher level of religious diversity than neighboring Arab countries, the UAE is an Islamic country.

The UAE actively encourages foreign companies to open branches in the country, so it is quite common and easy for foreign corporations to do so. Free-trade zones allow for 100 percent foreign ownership and no taxes. Nevertheless, it’s common and in some industries required for many companies outside the free-trade zone to have an Emirati sponsor or partner.

While the UAE is generally open for global business, recently Research in Motion (RIM) found itself at odds with the UAE government, which wanted to block Blackberry access in the country. RIM uses a proprietary encryption technology to protect data and sends it to offshore servers in North America. For some countries, such as the UAE, this data encryption is perceived as a national security threat. Some governments want to be able to access the communications of people they consider high security threats. The UAE government and RIM were able to resolve this issue, and Blackberry service was not suspended.

Human rights concerns have forced the UAE government to address the rights of children, women, minorities, and guest workers with legal consistency, a process that is continuing to evolve. Today, the UAE is focused on reducing its dependence on oil and its reliance on foreign workers by diversifying its economy and creating more opportunities for nationals through improved education and increased private sector employment.bWise: Business Wisdom Worldwide: U.A.E. (New York: Atma Global, 2011).

For the past fifty years, Africa has been ignored in large part by most global businesses. Initial efforts that focused on access to minerals, commodities, and markets have given way to extensive local corruption, wars, and high political and economic risk.

When the emerging markets came into focus in the late 1980s, global business turned its attention to Asia. However, that’s changing as companies look for the next growth opportunity. “A growing number of companies from the U.S., China, Japan, and Britain are eager to tap the potential growth of a continent with 1 billion people—especially given the weak outlook in many developed nations….Meanwhile, African governments are luring investments from Chinese companies seeking to tap the world’s biggest deposits of platinum, chrome, and diamonds.”Renee Bonorchis, “Africa Is Looking Like a Dealmaker’s Paradise,” BusinessWeek, September 30, 2010, accessed January 5, 2011, http://www.businessweek.com/magazine/content/10_41/b4198020648051.htm.

Within the continent, local companies are starting to and expanding to compete with global companies. These homegrown firms have a sense of African solidarity.

Big obstacles for businesses remain. Weak infrastructure means higher energy costs and trouble moving goods between countries. Cumbersome trade tariffs deter investment in new African markets. And the majority of the people in African countries live well below the poverty line, limiting their spending power.

Yet many African companies are finding ways around these barriers. Nigerian fertilizer company, Notore Chemicals Ltd., for example, has gone straight to governments to pitch the benefits of improved regional trade, and recently established a distribution chain that the company hopes will stretch across the 20 nations of Francophone Africa.Will Connors and Sarah Childress, “Africa’s Local Champions Begin to Spread Out,” Wall Street Journal, May 26, 2010, accessed January 5, 2011, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748704912004575252593400609032.html.

While the focus remains on South Africa, it’s only a matter of time until businesses shift their attention to other African nations. Political unrest, poverty, and corruption remain persistent challenges for the entire continent. A key factor in the continent’s success will be its ability to achieve political stability and calm the social unrest that has fueled regional civil conflicts.

Africa has some of the lowest Internet access in the world, and yet Google has been attracted to the continent by its growth potential. Africa with its one billion people is an exciting growth market for many companies.

“The Internet is not an integral part of everyday life for people in Africa,” said Joe Mucheru of Google’s Kenya office…

[Yet] Google executives say Africa represents one of the fastest growth rates for Internet use in the world. Nigeria already has about 24 million users and South Africa and Kenya aren’t far behind, according to World Bank and research sites like Internet World Stats…