This chapter explores currencies, foreign exchange rates, and how they are determined. It also discusses the global capital markets—the key components and how they impact global business. Foreign exchange is one aspect of the global capital markets. Companies access the global capital markets to utilize both the debt and equity markets; these are important for growth. Being able to access transparent and efficient capital markets around the world is another important component in the flattening world for global firms. Finally, this chapter discusses how the expansion of the global capital markets has benefited entrepreneurship and venture capitalists.

Most people in North America are familiar with the name Walmart. It conjures up an image of a gigantic, box-like store filled with a wide range of essential and nonessential products. What’s less known is that Walmart is the world’s largest company, in terms of revenues, as ranked by the Fortune 500 in 2010. With $408 billion in sales, it operates in fifteen global markets and has 4,343 stores outside of the United States, which amounts to about 50 percent of its total stores. More than 700,000 people work for Walmart internationally. With numbers like this, it’s easy to see how important the global markets have become for this company.“Walmart Stores Inc. Data Sheet—Worldwide Unit Details November 2010,” Walmart Corporation, accessed May 25, 2011, http://walmartstores.com/pressroom/news/10497.aspx.

Walmart’s strength comes from the upper hand it has in its negotiations with suppliers around the world. Suppliers are motivated to negotiate with Walmart because of the huge sales volume the stores offer manufacturers. The business rationale for many suppliers is that while they may lose a certain percentage of profitability per product, the overall sales volume of an order from Walmart can make them far more money overall than orders from most other stores. Walmart’s purchasing professionals are known for being aggressive negotiators on purchases and for extracting the best terms for the company.

In order to buy goods from around the world, Walmart has to deal extensively in different currencies. Small changes in the daily foreign currency market can significantly impact the costs for Walmart and in turn both its profitability and that of its global suppliers.

A company like Walmart needs foreign exchange and capital for different reasons, including the following common operational uses:

To illustrate this impact of foreign currency, let’s look at the currency of China, the renminbi (RMB), and its impact on a global business like Walmart. Many global analysts argue that the Chinese government tries to keep the value of its currency low or cheap to help promote exports. When the local RMB is valued cheaply or low, Chinese importers that buy foreign goods find that the prices are more expensive and higher.

However, Chinese exporters, those businesses that sell goods and services to foreign buyers, find that sales increase because their prices are cheaper or lower for the foreign buyers. Economists say that the Chinese government has intervened to keep the renminbi cheap in order to keep Chinese exports cheap; this has led to a huge trade surplus with the United States and most of the world. Each country tries to promote its exports to generate a trade advantage or surplus in its favor. When China has a trade surplus, it means the other country or countries are running trade deficits, which has “become an irritant to a lot of China’s trading partners and those who are competing with China to sell goods around the world.”David Barboza, “Currency Fight with China Divides U.S. Business,” New York Times, November 16, 2010, accessed May 25, 2011, http://www.nytimes.com/2010/11/17/business/global/17yuan.html?_r=1&pagewanted=2.

For Walmart, an American company, a cheap renminbi means that it takes fewer US dollars to buy Chinese products. Walmart can then buy cheap Chinese products, add a small profit margin, and then sell the goods in the United States at a price lower than what its competitors can offer. If the Chinese RMB increased in value, then Walmart would have to spend more US dollars to buy the same products, whether the products are clothing, electronics, or furniture. Any increase in cost for Walmart will mean an increase in cost for their customers in the United States, which could lead to a decrease in sales. So we can see why Walmart would be opposed to an increase in the value of the RMB.

To manage this currency concern, Walmart often requires that the currency exchange rate be fixed in its purchasing contracts with Chinese suppliers. By fixing the currency exchange rate, Walmart locks in its product costs and therefore its profitability. Fixing the exchange rate means setting the price that one currency will convert into another. This is how a company like Walmart can avoid unexpected drops or increases in the value of the RMB and the US dollar.

While global companies have to buy and sell in different currencies around the world, their primary goal is to avoid losses and to fix the price of the currency exchange so that they can manage their profitability with surety. This chapter takes a look at some of the currency tools that companies use to manage this risk.

Global firms like Walmart often set up local operations that help them balance or manage their risk by doing business in local currencies. Walmart now has 304 stores in China. Each store generates sales in renminbi, earning the company local currency that it can use to manage its local operations and to purchase local goods for sale in its other global markets.David Barboza, “Currency Fight with China Divides U.S. Business,” New York Times, November 16, 2010, accessed May 25, 2011, http://www.nytimes.com/2010/11/17/business/global/17yuan.html?_r=1&pagewanted=2.

(AACSB: Ethical Reasoning, Multiculturalism, Reflective Thinking, Analytical Skills)

In order to understand the global financial environment, how capital markets work, and their impact on global business, we need to first understand how currencies and foreign exchange rates work.

Briefly, currencyAny form of money in general circulation in a country. is any form of money in general circulation in a country. What exactly is a foreign exchange? In essence, foreign exchangeMoney denominated in the currency of another country. Money can also be denominated in the currency of a group of countries, such as the euro. is money denominated in the currency of another country or—now with the euro—a group of countries. Simply put, an exchange rateThe rate at which the market converts one currency into another. is defined as the rate at which the market converts one currency into another.

Any company operating globally must deal in foreign currencies. It has to pay suppliers in other countries with a currency different from its home country’s currency. The home country is where a company is headquartered. The firm is likely to be paid or have profits in a different currency and will want to exchange it for its home currency. Even if a company expects to be paid in its own currency, it must assess the risk that the buyer may not be able to pay the full amount due to currency fluctuations.

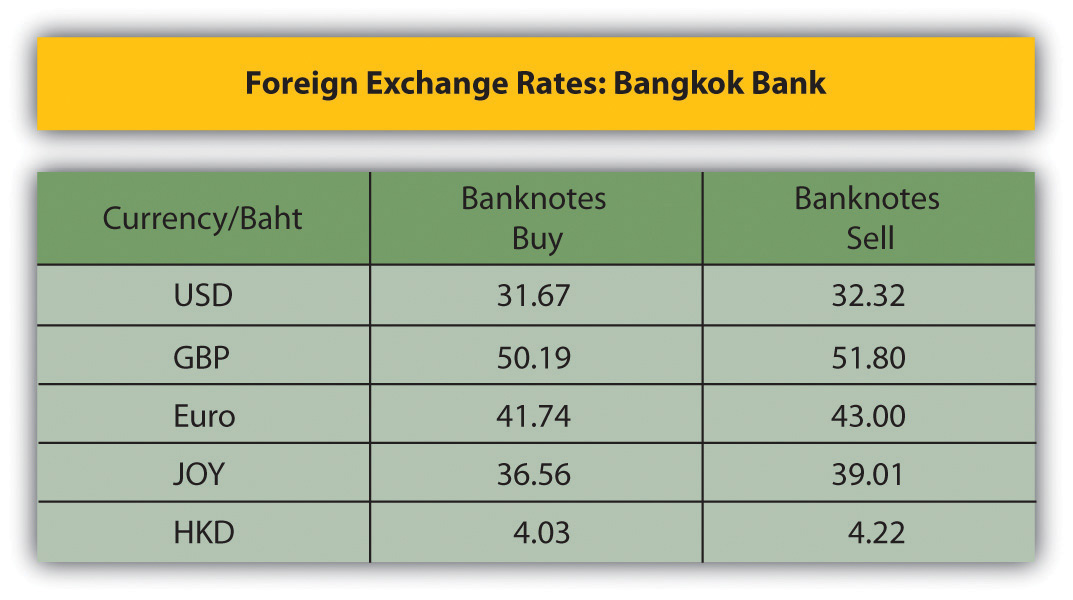

If you have traveled outside of your home country, you may have experienced the currency market—for example, when you tried to determine your hotel bill or tried to determine if an item was cheaper in one country versus another. In fact, when you land at an airport in another country, you’re likely to see boards indicating the foreign exchange rates for major currencies. These rates include two numbers: the bid and the offer. The bid (or buy)The price at which a bank or financial service firm is willing to buy a specific currency. is the price at which a bank or financial services firm is willing to buy a specific currency. The ask (or the offer or sell)Quote that refers to the price at which a bank or financial services firm is willing to sell that currency., refers to the price at which a bank or financial services firm is willing to sell that currency. Typically, the bid or the buy is always cheaper than the sell; banks make a profit on the transaction from that difference. For example, imagine you’re on vacation in Thailand and the exchange rate board indicates that the Bangkok Bank is willing to exchange currencies at the following rates (see the following figure). GBP refers to the British pound; JPY refers to the Japanese yen; and HKD refers to the Hong Kong dollar, as shown in the following figure. Because there are several countries that use the dollar as part or whole of their name, this chapter clearly states “US dollar” or uses US$ or USD when referring to American currency.

This chart tells us that when you land in Thailand, you can use 1 US dollar to buy 31.67 Thai baht. However, when you leave Thailand and decide that you do not need to take all your baht back to the United States, you then convert baht back to US dollars. We then have to use more baht—32.32 according to the preceding figure—to buy 1 US dollar. The spreadThe difference between the bid and the ask. This is the profit made for each unit of currency bought and sold. between these numbers, 0.65 baht, is the profit that the bank makes for each US dollar bought and sold. The bank charges a fee because it performed a service—facilitating the currency exchange. When you walk through the airport, you’ll see more boards for different banks with different buy and sell rates. While the difference may be very small, around 0.1 baht, these numbers add up if you are a global company engaged in large foreign exchange transactions. Accordingly, global firms are likely to shop around for the best rates before they exchange any currencies.

The foreign exchange market (or FX market) is the mechanism in which currencies can be bought and sold. A key component of this mechanism is pricing or, more specifically, the rate at which a currency is bought or sold. We’ll cover the determination of exchange rates more closely in this section, but first let’s understand the purpose of the FX market. International businesses have four main uses of the foreign exchange markets.

Companies, investors, and governments want to be able to convert one currency into another. A company’s primary purposes for wanting or needing to convert currencies is to pay or receive money for goods or services. Imagine you have a business in the United States that imports wines from around the world. You’ll need to pay the French winemakers in euros, your Australian wine suppliers in Australian dollars, and your Chilean vineyards in pesos. Obviously, you are not going to access these currencies physically. Rather, you’ll instruct your bank to pay each of these suppliers in their local currencies. Your bank will convert the currencies for you and debit your account for the US dollar equivalent based on the exact exchange rate at the time of the exchange.

One of the biggest challenges in foreign exchange is the risk of rates increasing or decreasing in greater amounts or directions than anticipated. Currency hedgingRefers to the technique of protecting against the potential losses that result from adverse changes in exchange rates. refers to the technique of protecting against the potential losses that result from adverse changes in exchange rates. Companies use hedging as a way to protect themselves if there is a time lag between when they bill and receive payment from a customer. Conversely, a company may owe payment to an overseas vendor and want to protect against changes in the exchange rate that would increase the amount of the payment. For example, a retail store in Japan imports or buys shoes from Italy. The Japanese firm has ninety days to pay the Italian firm. To protect itself, the Japanese firm enters into a contract with its bank to exchange the payment in ninety days at the agreed-on exchange rate. This way, the Japanese firm is clear about the amount to pay and protects itself from a sudden depreciation of the yen. If the yen depreciates, more yen will be required to purchase the same euros, making the deal more expensive. By hedging, the company locks in the rate.

Arbitrage is the simultaneous and instantaneous purchase and sale of a currency for a profit. Advances in technology have enabled trading systems to capture slight differences in price and execute a transaction, all within seconds. Previously, arbitrage was conducted by a trader sitting in one city, such as New York, monitoring currency prices on the Bloomberg terminal. Noticing that the value of a euro is cheaper in Hong Kong than in New York, the trader could then buy euros in Hong Kong and sell them in New York for a profit. Today, such transactions are almost all handled by sophisticated computer programs. The programs constantly search different exchanges, identify potential differences, and execute transactions, all within seconds.

Speculation refers to the practice of buying and selling a currency with the expectation that the value will change and result in a profit. Such changes could happen instantly or over a period of time.

High-risk, speculative investments by nonfinance companies are less common these days than the current news would indicate. While companies can engage in all four uses discussed in this section, many companies have determined over the years that arbitrage and speculation are too risky and not in alignment with their core strategies. In essence, these companies have determined that a loss due to high-risk or speculative investments would be embarrassing and inappropriate for their companies.

There are several ways to quote currency, but let’s keep it simple. In general, when we quote currencies, we are indicating how much of one currency it takes to buy another currency. This quote requires two components: the base currencyThe currency that is to be purchased with another currency and is noted in the denominator. and the quoted currencyThe currency with which another currency is to be purchased.. The quoted currency is the currency with which another currency is to be purchased. In an exchange rate quote, the quoted currency is typically the numerator. The base currency is the currency that is to be purchased with another currency, and it is noted in the denominator. For example, if we are quoting the number of Hong Kong dollars required to purchase 1 US dollar, then we note HKD 8 / USD 1. (Note that 8 reflects the general exchange rate average in this example.) In this case, the Hong Kong dollar is the quoted currency and is noted in the numerator. The US dollar is the base currency and is noted in the denominator. We read this quote as “8 Hong Kong dollars are required to purchase 1 US dollar.” If you get confused while reviewing exchanging rates, remember the currency that you want to buy or sell. If you want to sell 1 US dollar, you can buy 8 Hong Kong dollars, using the example in this paragraph.

Additionally, there are two methods—the American termsAlso known as US terms, American terms are from the point of view of someone in the United States. In this approach, foreign exchange rates are expressed in terms of how many US dollars can be exchanged for one unit of another currency (the non-US currency is the base currency). and the European termsForeign exchange rates are expressed in terms of how many currency units can be exchanged for one US dollar (the US dollar is the base currency). For example, the pound-dollar quote in European terms is £0.64/US$1 (£/US$1).—for noting the base and quoted currency. These two methods, which are also known as direct and indirect quotes, are opposite based on each reference point. Let’s understand what this means exactly.

The American terms, also known as US terms, are from the point of view of someone in the United States. In this approach, foreign exchange rates are expressed in terms of how many US dollars can be exchanged for one unit of another currency (the non-US currency is the base currency). For example, a dollar-pound quote in American terms is USD/GP (US$/£) equals 1.56. This is read as “1.56 US dollars are required to buy 1 pound sterling.” This is also called a direct quoteStates the domestic currency price of one unit of foreign currency. For example, €0.78/US$1. We read this as “it takes 0.78 of a euro to buy 1 US dollar.” In a direct quote, the domestic currency is a variable amount and the foreign currency is fixed at one unit., which states the domestic currency price of one unit of foreign currency. If you think about this logically, a business that needs to buy a foreign currency needs to know how many US dollars must be sold in order to buy one unit of the foreign currency. In a direct quote, the domestic currency is a variable amount and the foreign currency is fixed at one unit.

Conversely, the European terms are the other approach for quoting rates. In this approach, foreign exchange rates are expressed in terms of how many currency units can be exchanged for a US dollar (the US dollar is the base currency). For example, the pound-dollar quote in European terms is £0.64/US$1 (£/US$1). While this is a direct quote for someone in Europe, it is an indirect quoteStates the price of the domestic currency in foreign currency terms. For example, US$1.28/€1. We read this as “it takes 1.28 US dollars to buy 1 euro.” In an indirect quote, the foreign currency is a variable amount and the domestic currency is fixed at one unit. in the United States. An indirect quote states the price of the domestic currency in foreign currency terms. In an indirect quote, the foreign currency is a variable amount and the domestic currency is fixed at one unit.

A direct and an indirect quote are simply reverse quotes of each other. If you have either one, you can easily calculate the other using this simple formula:

direct quote = 1 / indirect quote.To illustrate, let’s use our dollar-pound example. The direct quote is US$1.56 = 1/£0.64 (the indirect quote). This can be read as

1 divided by 0.64 equals 1.56.In this example, the direct currency quote is written as US$/£ = 1.56.

While you are performing the calculations, it is important to keep track of which currency is in the numerator and which is in the denominator, or you might end up stating the quote backward. The direct quote is the rate at which you buy a currency. In this example, you need US$1.56 to buy a British pound.

Tip: Many international business professionals become experienced over their careers and are able to correct themselves in the event of a mix-up between currencies. To illustrate using the example mentioned previously, the seasoned global professional knows that the British pound is historically higher in value than the US dollar. This means that it takes more US dollars to buy a pound than the other way around. When we say “higher in value,” we mean that the value of the British pound buys you more US dollars. Using this logic, we can then deduce that 1.56 US dollars are required to buy 1 British pound. As an international businessperson, we would know instinctively that it cannot be less—that is, only 0.64 US dollars to buy a British pound. This would imply that the dollar value was higher in value. While major currencies have changed significantly in value vis-à-vis each other, it tends to happen over long periods of time. As a result, this self-test is a good way to use logic to keep track of tricky exchange rates. It works best with major currencies that do not fluctuate greatly vis-à-vis others.

A useful side note: traders always list the base currency as the first currency in a currency pair. Let’s assume, for example, that it takes 85 Japanese yen to purchase 1 US dollar. A currency trader would note this as follows: USD 1 / JPY 85. This quote indicates that the base currency is the US dollar and 85 yen are required to purchase a dollar. This is also called a direct quote, although FX traders are more likely to call it an American rate rather than a direct rate. It can be confusing, but try to keep the logic of which currency you are selling and which you are buying clearly in your mind, and say the quote as full sentences in order to keep track of the currencies.

These days, you can easily use the Internet to access up-to-date quotes on all currencies, although the most reliable sites remain the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times, or any website of a trustworthy financial institution.

The exchange rates discussed in this chapter are spot rates—exchange rates that require immediate settlement with delivery of the traded currency. “Immediate” usually means within two business days, but it implies an “on the spot” exchange of the currencies, hence the term spot rate. The spot exchange rateThe exchange rate transacted at a particular moment by a buyer and seller of a currency. When we buy and sell our foreign currency at a bank or at American Express, it’s quoted as the rate for the day. For currency traders, the spot can change throughout the trading day, even by tiny fractions. is the exchange rate transacted at a particular moment by the buyer and seller of a currency. When we buy and sell our foreign currency at a bank or at American Express, it’s quoted at the rate for the day. For currency traders though, the spot can change throughout the trading day even by tiny fractions.

To illustrate, assume that you work for a clothing company in the United States and you want to buy shirts from either Malaysia or Indonesia. The shirts are exactly the same; only the price is different. (For now, ignore shipping and any taxes.) Assume that you are using the spot rate and are making an immediate payment. There is no risk of the currency increasing or decreasing in value. (We’ll cover forward rates in the next section.)

The currency in Malaysia is the Malaysian ringgit, which is abbreviated MYR. The supplier in Kuala Lumpur e-mails you the quote—you can buy each shirt for MYR 35. Let’s use a spot exchange rate of MYR 3.13 / USD 1.

The Indonesian currency is the rupiah, which is abbreviated as Rp. The supplier in Jakarta e-mails you a quote indicating that you can buy each shirt for Rp 70,000. Use a spot exchange rate of Rp 8,960 / USD 1.

It would be easy to instinctively assume that the Indonesian firm is more expensive, but look more closely. You can calculate the price of one shirt into US dollars so that a comparison can be made:

For Malaysia: MYR 35 / MYR 3.13 = USD 11.18 For Indonesia: Rp 70,000 / Rp 8,960 = USD 7.81Indonesia is the cheaper supplier for our shirts on the basis of the spot exchange rate.

There’s one more term that applies to the spot market—the cross rateThe exchange rate between two currencies, neither of which is the official currency in the country in which the quote is provided. This is the exchange rate between two currencies, neither of which is the official currency in the country in which the quote is provided. For example, if an exchange rate between the euro and the yen were quoted by an American bank on US soil, the rate would be a cross rate.

The most common cross-currency pairs are EUR/GBP, EUR/CHF, and EUR/JPY. These currency pairs expand the trading possibilities in the foreign exchange market but are less actively traded than pairs that include the US dollar, which are called the “majors” because of their high degree of liquidity. The majors are EUR/USD, GBP/ USD, USD/JPY, USD/CAD (Canadian dollar), USD/CHF (Swiss franc), and USD/AUD (Australian dollar). Despite the changes in the international monetary system and the expansion of the capital markets, the currency market is really a market of dollars and nondollars. The dollar is still the reserve currency for the world’s central banks. Table 7.1 "Currency Cross Rates" contains some currency cross rates between the major currencies. We can see, for example, that the rate for the cross-currency pair of EUR/GBP is 1.1956. This is read as “it takes 1.1956 euros to buy one British pound.” Another example is the EUR/JPY rate, which is 0.00901. However, a seasoned trader would not say that it takes 0.00901 euros to buy 1 Japanese yen. He or she would instinctively know to quote the currency pair as the JPY/EUR rate or—more specifically—that it takes 111.088 yen to purchase 1 euro.

Table 7.1 Currency Cross Rates

| Currency codes / names | United Kingdom Pound | Canadian Dollar | Euro | Hong Kong Dollar | Japanese Yen | Swiss Franc | US Dollar | Chinese Yuan Renminbi |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GBP | 1 | 0.6177 | 0.8374 | 0.08145 | 0.007544 | 0.6455 | 0.633 | 0.09512 |

| CAD | 1.597 | 1 | 1.3358 | 0.1299 | 0.012032 | 1.0296 | 1.0095 | 0.1517 |

| EUR | 1.1956 | 0.7499 | 1 | 0.09748 | 0.00901 | 0.771 | 0.7563 | 0.1136 |

| HKD | 12.2896 | 7.7092 | 10.2622 | 1 | 0.09267 | 7.9294 | 7.7749 | 1.1682 |

| JPY | 132.754 | 83.2905 | 111.088 | 10.8083 | 1 | 85.65 | 84.001 | 12.6213 |

| CHF | 1.5512 | 0.9732 | 1.2981 | 0.1263 | 0.011696 | 1 | 0.9815 | 0.1475 |

| USD | 1.5807 | 0.9915 | 1.3232 | 0.1287 | 0.011919 | 1.0199 | 1 | 0.1503 |

| CNY | 10.5218 | 6.6002 | 8.8075 | 0.8565 | 0.07934 | 6.7887 | 6.6565 | 1 |

| Note: The official name for the Chinese currency is renminbi and the main unit of the currency is the yuan. | ||||||||

| Source: “Currency Cross Rates: Results,” Oanda, accessed May 25, 2011, http://www.oanda.com/currency/cross- rate/result?quotes=GBP"es=CAD"es=EUR"es=HKD"es=JPY"es= CHF"es=USD"es=CNY&go=Get+my+Table+++. | ||||||||

The forward exchange rateThe rate at which two parties agree to exchange currency and execute a deal at some specific point in the future, usually 30 days, 60 days, 90 days, or 180 days in the future. is the exchange rate at which a buyer and a seller agree to transact a currency at some date in the future. Forward rates are really a reflection of the market’s expectation of the future spot rate for a currency. The forward marketThe currency market for transactions at forward rates. is the currency market for transactions at forward rates. In the forward markets, foreign exchange is always quoted against the US dollar. This means that pricing is done in terms of how many US dollars are needed to buy one unit of the other currency. Not all currencies are traded in the forward market, as it depends on the demand in the international financial markets. The majors are routinely traded in the forward market.

For example, if a US company opted to buy cell phones from China with payment due in ninety days, it would be able to access the forward market to enter into a forward contract to lock in a future price for its payment. This would enable the US firm to protect itself against a depreciation of the US dollar, which would require more dollars to buy one Chinese yuan. A forward contractA contract that requires the exchange of an agreed-on amount of a currency on an agreed-on date and a specific exchange rate. is a contract that requires the exchange of an agreed-on amount of a currency on an agreed-on date and a specific exchange rate. Most forward contracts have fixed dates at 30, 90, or 180 days. Custom forward contracts can be purchased from most financial firms. Forward contracts, currency swaps, options, and futures all belong to a group of financial instruments called derivatives. In the term’s broadest definition, derivativesFinancial instruments whose underlying value comes from (derives from) other financial instruments or commodities. are financial instruments whose underlying value comes from (derives from) other financial instruments or commodities—in this case, another currency.

Swaps, options, and futures are three additional currency instruments used in the forward market.

A currency swapA simultaneous buy and sell of a currency for two different dates. is a simultaneous buy and sell of a currency for two different dates. For example, an American computer firm buys (imports) components from China. The firm needs to pay its supplier in renminbi today. At the same time, the American computer is expecting to receive RMB in ninety days for its netbooks sold in China. The American firm enters into two transactions. First, it exchanges US dollars and buys yuan renminbi today so that it can pay its supplier. Second, it simultaneously enters into a forward contract to sell yuan and buy dollars at the ninety-day forward rate. By entering into both transactions, the firm is able to reduce its foreign exchange rate risk by locking into the price for both.

Currency optionsThe option or the right, but not the obligation, to exchange a specific amount of currency on a specific future date and at a specific agreed-on rate. Because a currency option is a right but not a requirement, the parties in an option do not have to actually exchange the currencies if they choose not to. are the option or the right—but not the obligation—to exchange a specific amount of currency on a specific future date and at a specific agreed-on rate. Since a currency option is a right but not a requirement, the parties in an option do not have to actually exchange the currencies if they choose not to. This is referred to as not exercising an option.

Currency futures contractsContracts that require the exchange of a specific amount of currency at a specific future date and at a specific exchange rate. are contracts that require the exchange of a specific amount of currency at a specific future date and at a specific exchange rate. Futures contracts are similar to but not identical to forward contracts.

Futures contracts are actively traded on exchanges, and the terms are standardized. As a result, futures contracts have clearinghouses that guarantee the transactions, substantially reducing any risk of default by either party. Forward contracts are private contracts between two parties and are not standardized. As a result, the parties have a higher risk of defaulting on a contract.

The settlement of a forward contract occurs at the end of the contract. Futures contracts are marked-to-market daily, which means that daily changes are settled day by day until the end of the contract. Furthermore, the settlement of a futures contract can occur over a range of dates. Forward contracts, on the other hand, only have one settlement date at the end of the contract.

Futures contracts are frequently employed by speculators, who bet on the direction in which a currency’s price will move; as a result, futures contracts are usually closed out prior to maturity and delivery usually never happens. On the other hand, forward contracts are mostly used by companies, institutions, or hedgers that want to eliminate the volatility of a currency’s price in the future, and delivery of the currency will usually take place.

Companies routinely use these tools to manage their exposure to currency risk. One of the complicating factors for companies occurs when they operate in countries that limit or control the convertibility of currency. Some countries limit the profits (currency) a company can take out of a country. As a result, many companies resort to countertrade, where companies trade goods and services for other goods and services and actual monies are less involved.

The challenge for companies is to operate in a world system that is not efficient. Currency markets are influenced not only by market factors, inflation, interest rates, and market psychology but also—more importantly—by government policy and intervention. Many companies move their production and operations to overseas locations to manage against unforeseen currency risks and to circumvent trade barriers. It’s important for companies to actively monitor the markets in which they operate around the world.

In this section you learned about the following:

(AACSB: Reflective Thinking, Analytical Skills)

A capital marketMarkets in which people, companies, and governments with more funds than they need transfer those funds to people, companies, or governments that have a shortage of funds. Capital markets promote economic efficiency by transferring money from those who do not have an immediate productive use for it to those who do. Capital markets provide forums and mechanisms for governments, companies, and people to borrow or invest (or both) across national boundaries. is basically a system in which people, companies, and governments with an excess of funds transfer those funds to people, companies, and governments that have a shortage of funds. This transfer mechanism provides an efficient way for those who wish to borrow or invest money to do so. For example, every time someone takes out a loan to buy a car or a house, they are accessing the capital markets. Capital markets carry out the desirable economic function of directing capital to productive uses.

There are two main ways that someone accesses the capital markets—either as debt or equity. While there are many forms of each, very simply, debtMoney that’s borrowed and must be repaid. The bond is the most common example of a debt instrument. is money that’s borrowed and must be repaid, and equityMoney that is invested in return for a percentage of ownership but is not guaranteed in terms of repayment. is money that is invested in return for a percentage of ownership but is not guaranteed in terms of repayment.

In essence, governments, businesses, and people that save some portion of their income invest their money in capital markets such as stocks and bonds. The borrowers (governments, businesses, and people who spend more than their income) borrow the savers’ investments through the capital markets. When savers make investments, they convert risk-free assets such as cash or savings into risky assets with the hopes of receiving a future benefit. Since all investments are risky, the only reason a saver would put cash at risk is if returns on the investment are greater than returns on holding risk-free assets. Basically, a higher rate of return means a higher risk.

For example, let’s imagine a beverage company that makes $1 million in gross sales. If the company spends $900,000, including taxes and all expenses, then it has $100,000 in profits. The company can invest the $100,000 in a mutual fund (which are pools of money managed by an investment company), investing in stocks and bonds all over the world. Making such an investment is riskier than keeping the $100,000 in a savings account. The financial officer hopes that over the long term the investment will yield greater returns than cash holdings or interest on a savings account. This is an example of a form of direct financeA company borrows directly by issuing securities to investors in the capital markets.. In other words, the beverage company bought a security issued by another company through the capital markets. In contrast, indirect financeInvolves a financial intermediary between the borrower and the saver. For example, if the company deposited the money in a savings account at their bank, and then the bank lends the money to a company (or another person), the bank is an intermediary. involves a financial intermediary between the borrower and the saver. For example, if the company deposited the money in a savings account, and then the savings bank lends the money to a company (or a person), the bank is an intermediary. Financial intermediaries are very important in the capital marketplace. Banks lend money to many people, and in so doing create economies of scale. This is one of the primary purposes of the capital markets.

Capital markets promote economic efficiency. In the example, the beverage company wants to invest its $100,000 productively. There might be a number of firms around the world eager to borrow funds by issuing a debt security or an equity security so that it can implement a great business idea. Without issuing the security, the borrowing firm has no funds to implement its plans. By shifting the funds from the beverage company to other firms through the capital markets, the funds are employed to their maximum extent. If there were no capital markets, the beverage company might have kept its $100,000 in cash or in a low-yield savings account. The other firms would also have had to put off or cancel their business plans.

International capital marketsGlobal markets where people, companies, and governments with more funds than they need transfer those funds to people, companies, or governments that have a shortage of funds. International capital markets provide forums and mechanisms for governments, companies, and people to borrow or invest (or both) across national boundaries. are the same mechanism but in the global sphere, in which governments, companies, and people borrow and invest across national boundaries. In addition to the benefits and purposes of a domestic capital market, international capital markets provide the following benefits:

The structure of the capital markets falls into two components—primary and secondary. The primary marketWhere new securities (stocks and bonds are the most common) are issued. The company receives the funds from this issuance or sale. is where new securities (stocks and bonds are the most common) are issued. If a corporation or government agency needs funds, it issues (sells) securities to purchasers in the primary market. Big investment banks assist in this issuing process as intermediaries. Since the primary market is limited to issuing only new securities, it is valuable but less important than the secondary market.

The vast majority of capital transactions take place in the secondary marketThe secondary market includes stock exchanges (the New York Stock Exchange, the London Stock Exchange, and the Tokyo Nikkei), bond markets, and futures and options markets, among others. Secondary markets provide a mechanism for the risk of a security to be spread to more participants by enabling participants to buy and sell a security (debt or equity). Unlike the primary market, the company issuing the security does not receive any direct funds from the secondary market.. The secondary market includes stock exchanges (the New York Stock Exchange, the London Stock Exchange, and the Tokyo Nikkei), bond markets, and futures and options markets, among others. All these secondary markets deal in the trade of securities. The term securitiesIncludes a wide range of debt- and equity-based financial instruments. includes a wide range of financial instruments. You’re probably most familiar with stocks and bonds. Investors have essentially two broad categories of securities available to them: equity securities, which represent ownership of a part of a company, and debt securities, which represent a loan from the investor to a company or government entity.

Creditors, or debt holders, purchase debt securities and receive future income or assets in return for their investment. The most common example of a debt instrument is the bondA debt instrument. When investors buy bonds, they are lending the issuers of the bonds their money. In return, they typically receive interest at a fixed rate for a specified period of time.. When investors buy bonds, they are lending the issuers of the bonds their money. In return, they will receive interest payments usually at a fixed rate for the life of the bond and receive the principal when the bond expires. All types of organizations can issue bonds.

StocksA type of equity security that gives the holder an ownership (or a share) of a company’s assets and earnings. are the type of equity security with which most people are familiar. When investors buy stock, they become owners of a share of a company’s assets and earnings. If a company is successful, the price that investors are willing to pay for its stock will often rise; shareholders who bought stock at a lower price then stand to make a profit. If a company does not do well, however, its stock may decrease in value and shareholders can lose money. Stock prices are also subject to both general economic and industry-specific market factors.

The key to remember with either debt or equity securities is that the issuing entity, a company or government, only receives the cash in the primary market issuance. Once the security is issued, it is traded; but the company receives no more financial benefit from that security. Companies are motivated to maintain the value of their equity securities or to repay their bonds in a timely manner so that when they want to borrow funds from or sell more shares in the market, they have the credibility to do so.

For companies, the global financial, including the currency, markets (1) provide stability and predictability, (2) help reduce risk, and (3) provide access to more resources. One of the fundamental purposes of the capital markets, both domestic and international, is the concept of liquidityIn capital markets, this refers to the ease by which shareholders and bondholders can buy and sell their securities or convert their investments into cash., which basically means being able to convert a noncash asset into cash without losing any of the principal value. In the case of global capital markets, liquidity refers to the ease and speed by which shareholders and bondholders can buy and sell their securities and convert their investment into cash when necessary. Liquidity is also essential for foreign exchange, as companies don’t want their profits locked into an illiquid currency.

Companies sell their stock in the equity markets. International equity markets consists of all the stock traded outside the issuing company’s home country. Many large global companies seek to take advantage of the global financial centers and issue stock in major markets to support local and regional operations.

For example, ArcelorMittal is a global steel company headquartered in Luxembourg; it is listed on the stock exchanges of New York, Amsterdam, Paris, Brussels, Luxembourg, Madrid, Barcelona, Bilbao, and Valencia. While the daily value of the global markets changes, in the past decade the international equity markets have expanded considerably, offering global firms increased options for financing their global operations. The key factors for the increased growth in the international equity markets are the following:

Bonds are the most common form of debt instrument, which is basically a loan from the holder to the issuer of the bond. The international bond market consists of all the bonds sold by an issuing company, government, or entity outside their home country. Companies that do not want to issue more equity shares and dilute the ownership interests of existing shareholders prefer using bonds or debt to raise capital (i.e., money). Companies might access the international bond markets for a variety of reasons, including funding a new production facility or expanding its operations in one or more countries. There are several types of international bonds, which are detailed in the next sections.

A foreign bond is a bond sold by a company, government, or entity in another country and issued in the currency of the country in which it is being sold. There are foreign exchange, economic, and political risks associated with foreign bonds, and many sophisticated buyers and issuers of these bonds use complex hedging strategies to reduce the risks. For example, the bonds issued by global companies in Japan denominated in yen are called samurai bonds. As you might expect, there are other names for similar bond structures. Foreign bonds sold in the United States and denominated in US dollars are called Yankee bonds. In the United Kingdom, these foreign bonds are called bulldog bonds. Foreign bonds issued and traded throughout Asia except Japan, are called dragon bonds, which are typically denominated in US dollars. Foreign bonds are typically subject to the same rules and guidelines as domestic bonds in the country in which they are issued. There are also regulatory and reporting requirements, which make them a slightly more expensive bond than the Eurobond. The requirements add small costs that can add up given the size of the bond issues by many companies.

A Eurobond is a bond issued outside the country in whose currency it is denominated. Eurobonds are not regulated by the governments of the countries in which they are sold, and as a result, Eurobonds are the most popular form of international bond. A bond issued by a Japanese company, denominated in US dollars, and sold only in the United Kingdom and France is an example of a Eurobond.

A global bond is a bond that is sold simultaneously in several global financial centers. It is denominated in one currency, usually US dollars or Euros. By offering the bond in several markets at the same time, the company can reduce its issuing costs. This option is usually reserved for higher rated, creditworthy, and typically very large firms.

As the international bond market has grown, so too have the creative variations of bonds, in some cases to meet the specific needs of a buyer and issuer community. Sukuk, an Arabic word, is a type of financing instrument that is in essence an Islamic bond. The religious law of Islam, Sharia, does not permit the charging or paying of interest, so Sukuk securities are structured to comply with the Islamic law. “An IMF study released in 2007 noted that the Issuance of Islamic securities (sukuk) rose fourfold to $27 billion during 2004–06. While 14 types of sukuk are recognized by the Accounting and Auditing Organization of Islamic Finance Institutions, their structure relies on one of the three basic forms of legitimate Islamic finance, murabahah (synthetic loans/purchase orders), musharakah/mudharabah (profit-sharing arrangements), and ijara (sale-leasebacks), or a combination thereof.”Andy Jobst, Peter Kunzel, Paul Mills, and Amadou Sy, “Islamic Finance Expanding Rapidly,” International Monetary Fund, September 19, 2007, accessed February 2, 2011, http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/survey/so/2007/res0919b.htm.

The Economist notes “that by 2000, there were more than 200 Islamic banks…and today $700 billion of global assets are said to comply with sharia law. Even so, traditional finance houses rather than Islamic institutions continue to handle most Gulf oil money and other Muslim wealth.”

“More worrying still, the rules for Islamic finance are not uniform around the world. A Kuwaiti Muslim cannot buy a Malaysian sukuk (sharia-compliant bond) because of differing definitions of what constitutes usury (interest). Indeed, a respected Islamic jurist recently denounced most sukuk as godless. Nor are banking licenses granted easily in most Muslim countries. That is why big Islamic banks are so weak. Often they are little more than loose collections of subsidiaries. They also lack home-grown talent: most senior staff are poached from multinationals.” But in 2009, one entrepreneur, Adnan Yousif, made headlines as he tried to change that and create the world’s biggest Islamic bank. While his efforts are still in progress, it’s clear that Islamic banking is a growing and profitable industry niche.“Godly but Ambitious,” Economist, June 18, 2009, accessed February 2, 2011, http://www.economist.com/node/13856281.

The Eurocurrency markets originated in the 1950s when communist governments in Eastern Europe became concerned that any deposits of their dollars in US banks might be confiscated or blocked for political reasons by the US government. These communist governments addressed their concerns by depositing their dollars into European banks, which were willing to maintain dollar accounts for them. This created what is known as the EurodollarUS dollars deposited in any bank outside the United States.—US dollars deposited in European banks. Over the years, banks in other countries, including Japan and Canada, also began to hold US dollar deposits and now Eurodollars are any dollar deposits in a bank outside the United States. (The prefix Euro- is now only a historical reference to its early days.) An extension of the Eurodollar is the EurocurrencyA currency on deposit outside its country of issue., which is a currency on deposit outside its country of issue. While Eurocurrencies can be in any denominations, almost half of world deposits are in the form of Eurodollars.

The Euroloan market is also a growing part of the Eurocurrency market. The Euroloan market is one of the least costly for large, creditworthy borrowers, including governments and large global firms. Euroloans are quoted on the basis of LIBORThe London Interbank Offer Rate. It is the interest rate that London banks charge each other for Eurocurrency loans., the London Interbank Offer Rate, which is the interest rate at which banks in London charge each other for short-term Eurocurrency loans.

The primary appeal of the Eurocurrency market is that there are no regulations, which results in lower costs. The participants in the Eurocurrency markets are very large global firms, banks, governments, and extremely wealthy individuals. As a result, the transaction sizes tend to be large, which provides an economy of scale and nets overall lower transaction costs. The Eurocurrency markets are relatively cheap, short-term financing options for Eurocurrency loans; they are also a short-term investing option for entities with excess funds in the form of Eurocurrency deposits.

The first tier of centers in the world are the world financial centersCentral points for business and finance. They are usually home to major corporations and banks or at least regional headquarters for global firms. They all have at least one globally active stock exchange. While their actual order of importance may differ both on the ranking format and the year, the following cities rank as global financial centers: New York, London, Tokyo, Hong Kong, Singapore, Chicago, Zurich, Geneva, and Sydney., which are in essence central points for business and finance. They are usually home to major corporations and banks or at least regional headquarters for global firms. They all have at least one globally active stock exchange. While their actual order of importance may differ both on the ranking format and the year, the following cities rank as global financial centers: New York, London, Tokyo, Hong Kong, Singapore, Chicago, Zurich, Geneva, and Sydney.

The Economist reported in December 2009 that a “poll of Bloomberg subscribers in October found that Britain had dropped behind Singapore into third place as the city most likely to be the best financial hub two years from now. A survey of executives…by Eversheds, a law firm, found that Shanghai could overtake London within the next ten years.”“Foul-Weather Friends,” Economist, December 17, 2009, accessed February 2, 2011, http://www.economist.com/node/15127550. Many of these changes in rank are due to local costs, taxes, and regulations. London has become expensive for financial professionals, and changes in the regulatory and political environment have also lessened the city’s immediate popularity. However, London has remained a premier financial center for more than two centuries, and it would be too soon to assume its days as one of the global financial hubs is over.

In addition to the global financial centers are a group of countries and territories that constitute offshore financial centers. An offshore financial centerAn offshore financial center is a country or territory where there are few rules governing the financial sector as a whole and low overall taxes. is a country or territory where there are few rules governing the financial sector as a whole and low overall taxes. As a result, many offshore centers are called tax havens. Most of these countries or territories are politically and economically stable, and in most cases, the local government has determined that becoming an offshore financial center is its main industry. As a result, they invest in the technology and infrastructure to remain globally linked and competitive in the global finance marketplace.

Examples of well-known offshore financial centers include Anguilla, the Bahamas, the Cayman Islands, Bermuda, the Netherlands, the Antilles, Bahrain, and Singapore. They tend to be small countries or territories, and while global businesses may not locate any of their operations in these locations, they sometimes incorporate in these offshore centers to escape the higher taxes they would have to pay in their home countries and to take advantage of the efficiencies of these financial centers. Many global firms may house financing subsidiaries in offshore centers for the same benefits. For example, Bacardi, the spirits manufacturer, has $6 billion in revenues, more than 6,000 employees worldwide, and twenty-seven global production facilities. The firm is headquartered in Bermuda, enabling it to take advantage of the lower tax rates and financial efficiencies for managing its global operations.

As a result of the size of financial transactions that flow through these offshore centers, they have been increasingly important in the global capital markets.

Offshore financial centers have also come under criticism. Many people criticize these countries because corporations and individuals hide wealth there to avoid paying taxes on it. Many offshore centers are countries that have a zero-tax basis, which has earned them the title of tax havens.

The Economist notes that offshore financial centers

are typically small jurisdictions, such as Macau, Bermuda, Liechtenstein or Guernsey, that make their living mainly by attracting overseas financial capital. What they offer foreign businesses and well-heeled individuals is low or no taxes, political stability, business-friendly regulation and laws, and above all discretion. Big, rich countries see OFCs as the weak link in the global financial chain…

The most obvious use of OFCs is to avoid taxes. Many successful offshore jurisdictions keep on the right side of the law, and many of the world's richest people and its biggest and most reputable companies use them quite legally to minimise their tax liability. But the onshore world takes a hostile view of them. Offshore tax havens have “declared economic war on honest US taxpayers,” says Carl Levin, an American senator. He points to a study suggesting that America loses up to $70 billion a year to tax havens…

Business in OFCs is booming, and as a group these jurisdictions no longer sit at the fringes of the global economy. Offshore holdings now run to $5 trillion–7 trillion, five times as much as two decades ago, and make up perhaps 6–8 percent of worldwide wealth under management, according to Jeffrey Owens, head of fiscal affairs at the OECD. Cayman, a trio of islands in the Caribbean, is the world's fifth-largest banking centre, with $1.4 trillion in assets. The British Virgin Islands (BVI) are home to almost 700,000 offshore companies.

All this has been very good for the OFCs’ economies. Between 1982 and 2003 they grew at an annual average rate per person of 2.8 percent, over twice as fast as the world as a whole (1.2 percent), according to a study by James Hines of the University of Michigan. Individual OFCs have done even better. Bermuda is the richest country in the world, with a GDP per person estimated at almost $70,000, compared with $43,500 for America…On average, the citizens of Cayman, Jersey, Guernsey and the BVI are richer than those in most of Europe, Canada and Japan. This has encouraged other countries with small domestic markets to set up financial centres of their own to pull in offshore money—most spectacularly Dubai but also Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Shanghai and even Sudan's Khartoum, not so far from war-ravaged Darfur.

Globalisation has vastly increased the opportunities for such business. As companies become ever more multinational, they find it easier to shift their activities and profits across borders and into OFCs. As the well-to-do lead increasingly peripatetic lives, with jobs far from home, mansions scattered across continents and investments around the world, they can keep and manage their wealth anywhere. Financial liberalisation—the elimination of capital controls and the like—has made all of this easier. So has the internet, which allows money to be shifted around the world quickly, cheaply and anonymously.Joanne Ramos, “Places in the Sun,” Economist, February 22, 2007, accessed March 2, 2011, http://www.economist.com/node/8695139.

For more on these controversial offshore centers, please see the full article at http://www.economist.com/node/8695139.

The role of international banks, investment banks, and securities firms has evolved in the past few decades. Let’s take a look at the primary purpose of each of these institutions and how it has changed, as many have merged to become global financial powerhouses.

Traditionally, international banks extended their domestic role to the global arena by servicing the needs of multinational corporations (MNC). These banks not only received deposits and made loans but also provided tools to finance exports and imports and offered sophisticated cash-management tools, including foreign exchange. For example, a company purchasing products from another country may need short-term financing of the purchase; electronic funds transfers (also called wires); and foreign exchange transactions. International banks provide all these services and more.

In broad strokes, there are different types of banks, and they may be divided into several groups on the basis of their activities. Retail banks deal directly with consumers and usually focus on mass-market products such as checking and savings accounts, mortgages and other loans, and credit cards. By contrast, private banks normally provide wealth-management services to families and individuals of high net worth. Business banks provide services to businesses and other organizations that are medium sized, whereas the clients of corporate banks are usually major business entities. Lastly, investment banks provide services related to financial markets, such as mergers and acquisitions. Investment banks also focused primarily on the creation and sale of securities (e.g., debt and equity) to help companies, governments, and large institutions achieve their financing objectives. Retail, private, business, corporate, and investment banks have traditionally been separate entities. All can operate on the global level. In many cases, these separate institutions have recently merged, or were acquired by another institution, to create global financial powerhouses that now have all types of banks under one giant, global corporate umbrella.

However the merger of all of these types of banking firms has created global economic challenges. In the United States, for example, these two types—retail and investment banks—were barred from being under the same corporate umbrella by the Glass-Steagall ActEnacted in 1932 during the Great Depression, the Glass-Steagall Act, officially called the Banking Reform Act of 1933, created the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporations (FDIC) and implemented bank reforms, beginning in 1932 and continuing through 1933. These reforms are credited with providing stability and reduced risk in the banking industry.. Enacted in 1932 during the Great Depression, the Glass-Steagall Act, officially called the Banking Reform Act of 1933, created the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporations (FDIC) and implemented bank reforms, beginning in 1932 and continuing through 1933. These reforms are credited with providing stability and reduced risk in the banking industry for decades. Among other things, it prohibited bank-holding companies from owning other financial companies. This served to ensure that investment banks and banks would remain separate—until 1999, when Glass-Steagall was repealed. Some analysts have criticized the repeal of Glass-Steagall as one cause of the 2007–8 financial crisis.

Because of the size, scope, and reach of US financial firms, this historical reference point is important in understanding the impact of US firms on global businesses. In 1999, once bank-holding companies were able to own other financial services firms, the trend toward creating global financial powerhouses increased, blurring the line between which services were conducted on behalf of clients and which business was being managed for the benefit of the financial company itself. Global businesses were also part of this trend, as they sought the largest and strongest financial players in multiple markets to service their global financial needs. If a company has operations in twenty countries, it prefers two or three large, global banking relationships for a more cost-effective and lower-risk approach. For example, one large bank can provide services more cheaply and better manage the company’s currency exposure across multiple markets. One large financial company can offer more sophisticated risk-management options and products. The challenge has become that in some cases, the party on the opposite side of the transaction from the global firm has turned out to be the global financial powerhouse itself, creating a conflict of interest that many feel would not exist if Glass-Steagall had not been repealed. The issue remains a point of ongoing discussion between companies, financial firms, and policymakers around the world. Meanwhile, global businesses have benefited from the expanded services and capabilities of the global financial powerhouses.

For example, US-based Citigroup is the world’s largest financial services network, with 16,000 offices in 160 countries and jurisdictions, holding 200 million customer accounts. It’s a financial powerhouse with operations in retail, private, business, and investment banking, as well as asset management. Citibank’s global reach make it a good banking partner for large global firms that want to be able to manage the financial needs of their employees and the company’s operations around the world.

In fact this strength is a core part of its marketing message to global companies and is even posted on its website (http://www.citigroup.com/citi/products/instinvest.htm): “Citi puts the world’s largest financial network to work for you and your organization.”

Outsourcing Day Trading to China

American and Canadian trading firms are hiring Chinese workers to “day trade” from China during the hours the American stock market is open. In essence, day trading or speculative trading occurs when a trader buys and sells stock quickly throughout the day in the hopes of making quick profits. The New York Times reported that as many as 10,000 Chinese, mainly young men, are busy working the night shift in Chinese cities from 9:30 p.m. to 4 a.m., which are the hours that the New York Stock Exchange is open in New York.

The motivation is severalfold. First, American and Canadian firms are looking to access wealthy Chinese clients who are technically not allowed to use Chinese currency to buy and sell shares on a foreign stock exchange. However, there are no restrictions for trading stocks in accounts owned by a foreign entity, which in this case usually belongs to the trading firms. Chinese traders also get paid less than their American and Canadian counterparts.

There are ethical concerns over this arrangement because it isn’t clear whether the use of traders in China violates American and Canadian securities laws. In a New York Times article quotes Thomas J. Rice, an expert in securities law at Baker & McKenzie, who states, “This is a jurisdictional mess for the U.S. regulators. Are these Chinese traders essentially acting as brokers? If they are, they would need to be registered in the U.S.” While the regulatory issues may not be clear, the trading firms are doing well and growing: “many Chinese day traders see this as an opportunity to quickly gain new riches.” Some American and Canadian trading firms see the opportunity to get “profit from trading operations in China through a combination of cheap overhead, rebates and other financial incentives from the major stock exchanges, and pent-up demand for broader investment options among China’s elite.”David Barboza, “Day Trading, Conducted Overnight, Grows in China,” New York Times, December 10, 2010.

(AACSB: Reflective Thinking, Analytical Skills)

Every start-up firm and young, growing business needs capital—money to invest to grow the business. Some companies access capital from the company founders or the friends and family of the founders. Growing companies that are profitable may be able to turn to banks and traditional lending companies. Another increasingly visible and popular source of capital is venture capital. Venture capital (VC) refers to the investment made in an early- or growth-stage company. Venture capitalistA person or investment firm that makes venture investments and brings managerial and technical expertise as well as capital to their investments. (also known as VC) refers to the investor.

One of the unintended benefits of the expansion of the global capital markets has been the expansion of international VC. Typically, VCs establish a venture fund with monies from institutions and individuals of high net worth. VCs, in turn, use the venture funds to invest in early- and growth-stage companies. VCs are characterized primarily by their investments in smaller, high-growth firms that are considered riskier than traditional investments. These investments are not liquid (i.e., they cannot be quickly bought and sold through the global financial markets). For this riskier and illiquid feature, VCs earn much higher rates of return that are sometimes astronomical if the VC times the exit correctly.

One of the factors that any VC assesses while determining whether or not to invest in a young and growing company is the exit strategyThe way a VC or investor can liquidate an investment, usually for a liquid security or cash.. The exit strategy is the way that a VC or investor can liquidate an investment, usually for a liquid security or cash. It’s great if a company does well, but any investor, including VCs, wants to know how and when they’re going to get their money out. While an initial public offering (IPO) is certainly a lucrative exit strategy, it’s not for every company. Many VCs also like to see a list of possible strategic acquirers.

Many large global firms also have internal investment groups that make corporate venture investments in early-stage and growing companies. These corporate VC firms may actually be the exit strategy and eventually acquire the young company if it fits their business objectives. This type of corporate VC is often called a strategic investor because they are more likely to place a higher priority on the strategic value of the investment rather than just the pure financial return on investment.

For example, US-based Intel Corporation, one of the world’s largest technology companies, has an internal group called Intel Capital. The vision of Intel Capital is “to be the preeminent global investing organization in the world” and its mission “to make and manage financially attractive investments in support of Intel’s strategic objectives.”“Intel Capital,” Intel Capital Corporation, accessed March 2, 2011, http://www.intel.com/about/companyinfo/capital/index.htm.

Intel Capital makes investments in companies around the world to encourage the development and deployment of new technologies, enter into or expand in new markets, and generate returns on their investments. “Since 1991, Intel Capital has invested more than USD 9.5 billion in over 1,050 companies in 47 countries. In that timeframe, 175 portfolio companies have gone public on various exchanges around the world and 241 were acquired or participated in a merger. In 2009, Intel Capital invested USD 327 million in 107 investments with approximately 50 percent of funds invested outside the U.S. and Canada.”“About Intel Capital,” Intel Capital Corporation, accessed March 2, 2011, http://www.intel.com/about/companyinfo/capital/info/earnings.htm.

Table 7.2 "Intel Capital Investments Announced in November 2010" shows a sample of the global investments made by Intel Capital.

Table 7.2 Intel Capital Investments Announced in November 2010

| Company | Country | Business |

|---|---|---|

| Althea Systems | India | Makes a cloud-based video platform to find and share online videos across devices (Shufflr is its social video browser) |

| Anobit | Israel | Memory signal processing technology |

| Boo-box | Brazil | Software-based ad system for social media |

| De Novo | Ukraine | Provides enterprise-class data centers and services in Ukraine |

| Iptego | Berlin | Makes software to optimize Next Generation Networks |

| Layar | Netherlands | Reality platform available on Android, iPhone, and Bada mobile devices |

| Rock Flow Dynamics | Russia | Makes modeling software that simulates fluid and gas filtration |

| Select-TV | Malaysia | Makes set-top boxes for IP TVs |

| Taifatech | Taiwan | Fabless semiconductor company that makes wireless system on a chip |

| WinChannel | Beijing | Makes software that manages replenishment orders, sales, inventory, and other activities in near-real time |

Source: Copyright Intel Capital, 2010.

As a result, the expanded global markets offer VCs access to (1) new potential investors in their venture funds; (2) a wider selection of firms in which to invest; (3) more exit strategies, including IPOs in other countries outside their home country; and (4) the opportunity for their portfolio companies to merge or be acquired by foreign firms. Tech-savvy American and European VCs have traced the source of the high-tech talent pool and increased their investments in growing companies in many countries, including Israel, China, India, Brazil, and Russia.

A July 2010 research survey conducted by Deloitte uncovered the following sentiments among VCs from around the world.

‘Traditionally strong markets like the U.S. and Europe will continue to be important hubs despite consolidation in the number of venture firms,’ said Mark Jensen, partner, Deloitte & Touche LLP and national managing partner for VC services. ‘However, the stage has now been set for emerging markets like China, India and Brazil to rise as drivers of innovation as they are increasingly becoming more competitive with the traditional markets.’…

Overall, only 34 percent of all respondents indicated that they expect to increase their investment activity outside their own country….The countries with the most interest in cross border investing include: France (56 percent), Israel (50 percent) and the United Kingdom (49 percent). Countries indicating the least interest in outside investing were Brazil (19 percent), India (15 percent) and China (11 percent).

‘The Asian markets, in particular, are abundant in entrepreneurial spirit, energy and a dedication from both the private and public sectors to push the economic growth pendulum as far as possible,’ said Trevor Loy, general partner of Flywheel Ventures. ‘The continued rapid growth of emerging markets is also creating a new source of customer revenue, investment capital, job creation, and shareholder liquidity for U.S. based technology start-ups, particularly those leveraging America’s deep research and development (R&D) resources to address critical infrastructure needs in energy, water, materials and communications.’…

Top challenges varied in countries around the globe with the exit market being cited the most in the United Kingdom (80 percent), Canada (75 percent), India (71 percent) and Israel (70 percent). Eighty-one percent of respondents in Brazil cited unfavorable tax policies as being a hindrance. An unstable regulatory environment was the most common factor cited by respondents in France (72 percent) and China (62 percent).

‘The challenges for a U.S. venture firm trying to do business in Europe include the current weakness in the euro-zone economy, language and cultural differences, and the tendency towards inflexible employment regulations,’ said Bruce Evans, managing director of Summit Partners. ‘On top of this, U.S. firms have to fund their European expansion from their own profits, and the proposed U.S. tax changes to carried interest—and the taxation of equity interests in fund managers more generally—would serve as an impediment to U.S. venture funds’ growth aspirations.’

‘Yet, opportunities remain as well,’ Evans continued. ‘The psychological make-up of successful, driven entrepreneurs in Europe mirrors what we have found in the U.S. In addition, the globalization of technology markets means that successful products are as likely to be developed in Europe as elsewhere. Finally, the days of missionary selling of venture capital in Europe are over, and today there is a broad understanding of our type of financing.’“U.S. Venture Capital Industry Expected to Shrink While Emerging Markets Grow: Deloitte, NVCA Study,” Deloitte Corporation, July 14, 2010, accessed February 2, 2011, http://www.deloitte.com/view/en_US/us/Insights/browse-by-role/media-role/a8e40f2f800d9210VgnVCM200000bb42f00aRCRD.htm.

In this section, you learned

One of the key factors that any VC assesses while determining whether or not to invest in a young and growing company is the exit strategy. The exit strategy is the way a VC or investor can liquidate investments, usually for a liquid security or cash. As a result, the expansion of the global capital markets has benefited VCs who now have more access to the following:

(AACSB: Reflective Thinking, Analytical Skills)

Young companies around the world now eagerly—and sometimes successfully—reach out to VCs in other countries. If you are a budding entrepreneur thinking about going the VC route to fund your business, it’s important to learn more about the industry and community. At the end of the day, money is what matters—it’s business for VCs. This is a harsh point of view for entrepreneurs, who are often quite emotional about their product or service. It can be hard to know just how to evaluate VCs. Here are some tips to follow no matter where in the world the entrepreneur or VCs are located.Sanjyot P. Dunung, Starting Your Business (New York: Business Expert Press, 2010).

Understand the nature of a VC. They are basically fund managers looking for high returns for their investors. Understand the VC’s portfolio’s mission and goals. Most have multiple funds in their portfolio each with different investment parameters based in part on the various investors. VC is an industry, and the VCs are your “customer.” You need to understand how the industry operates, how to get your “product” (i.e., your company) noticed, and how to close the sale (i.e., get your funding). While there are certainly nuances, treat it like a sales process from start to finish. Remember that VCs run a business, one that they are held accountable to by their investors. More often than not, the people you meet at a VC firm are not the actual investors (although the senior principals may have some of their own money in the fund); they just work for the VC firm.

VCs focus on market trends, whether it’s green technology, social networking websites, or the current perceived “hot” industry. While it’s still possible to get funding if you are not in a current trend, it’s certainly harder. VCs typically look at groups of investments and generally like to have funds with three or four companies out of ten providing exceptional returns. They expect the rest of the businesses in the portfolio to either be weak performers or to fail. Sounds harsh, perhaps, but this is purely statistical to the VC industry. It’s important to ask VCs about their expected returns. When VCs market their funds to potential global institutional and wealthy investors, they have to indicate a vision, strategy, and target range for returns to these potential “buyers”—that is, investors. If you’re beginning to think that a VC sounds suspiciously like an entrepreneur, you’re correct. You need to realize that in the same way you’re raising money from a VC, the VC is raising money from someone else.

Act the part. Be prepared. Conduct yourself professionally at all times. Dress and act like you’re going to a job interview—it’s quite similar. Don’t drop names or promise too much. Don’t make claims about your product or service that can’t be substantiated.

Again, your credibility will suffer even if you actually have a solid product or service. Go to any VC meeting with a clear presentation and detailed business plan. If you can’t answer a specific question, say so and promise to get back to them within a specified time frame with further information. Even if you don’t have an answer, be sure to get back to them later with a follow-up that indicates you are still researching the answer. Don’t act like you’re entitled to funding for any reason. You may think your idea is great, but VCs see many “great” ideas. Support your request for funding with clear business rationale and facts. Lose any attitude.

Look for mutual respect. Sure, you need money, but the VC needs to also be aware that they need good companies with solid ideas in order to be successful and profitable.

Is there a mutual acknowledgment of respect and that you both need each other to succeed? Many VCs appear to operate as if this isn’t the case. Just as you will likely turn to your VC for creative financing and exit strategies, the VC should respect your industry and management experiences. Success can only be achieved if there’s mutual respect and a focus on creating a win for all involved.