When the legal title to certain property is held by one person while another has the use and benefit of it, a relationship known as a trustThe holding of legal title by one party for the benefit of another. has been created. The trust developed centuries ago to get around various nuances and complexities, including taxes, of English real property law. The trustee has legal title and the beneficiary has “equitable title,” since the courts of equity would enforce the obligations of the trustee to honor the terms by which the property was conveyed to him. A typical trust might provide for the trustee to manage an estate for the grantor’s children, paying out income to the children until they are, say, twenty-one, at which time they would become legal owners of the property.

Trusts may be created by bequest in a will, by agreement of the parties, or by a court decree. However created, the trust is governed by a set of rules that grew out of the courts of equity. Every trust involves specific property, known as the res (rees; Latin for “thing”), and three parties, though the parties may be the same person.

Anyone who has legal capacity to make a contract may create a trust. The creator is known as the settlorGrantor; the one who creates a trust. or grantor. Trusts are created for many reasons; for example, so that a minor can have the use of assets without being able to dissipate them or so that a person can have a professional manage his money.

The trustee is the person or legal entity that holds the legal title to the res. Banks do considerable business as trustees. If the settlor should neglect to name a trustee, the court may name one. The trustee is a fiduciary of the trust beneficiary and will be held to the highest standard of loyalty. Not even an appearance of impropriety toward the trust property will be permitted. Thus a trustee may not loan trust property to friends, to a corporation of which he is a principal, or to himself, even if he is scrupulous to account for every penny and pays the principal back with interest. The trustee must act prudently in administering the trust.

The beneficiary is the person, institution, or other thing for which the trust has been created. Beneficiaries are not limited to one’s children or close friends; an institution, a corporation, or some other organization, such as a charity, can be a beneficiary of a trust, as can one’s pet dogs, cats, and the like. The beneficiary may usually sell or otherwise dispose of his interest in a trust, and that interest likewise can usually be reached by creditors. Note that the settlor may create a trust of which he is the beneficiary, just as he may create a trust of which he is the trustee.

Continental Bank & Trust Co. v. Country Club Mobile Estates, Ltd., (see Section 14.4.2 "Settlor’s Limited Power over the Trust"), considers a basic element of trust law: the settlor’s power over the property once he has created the trust.

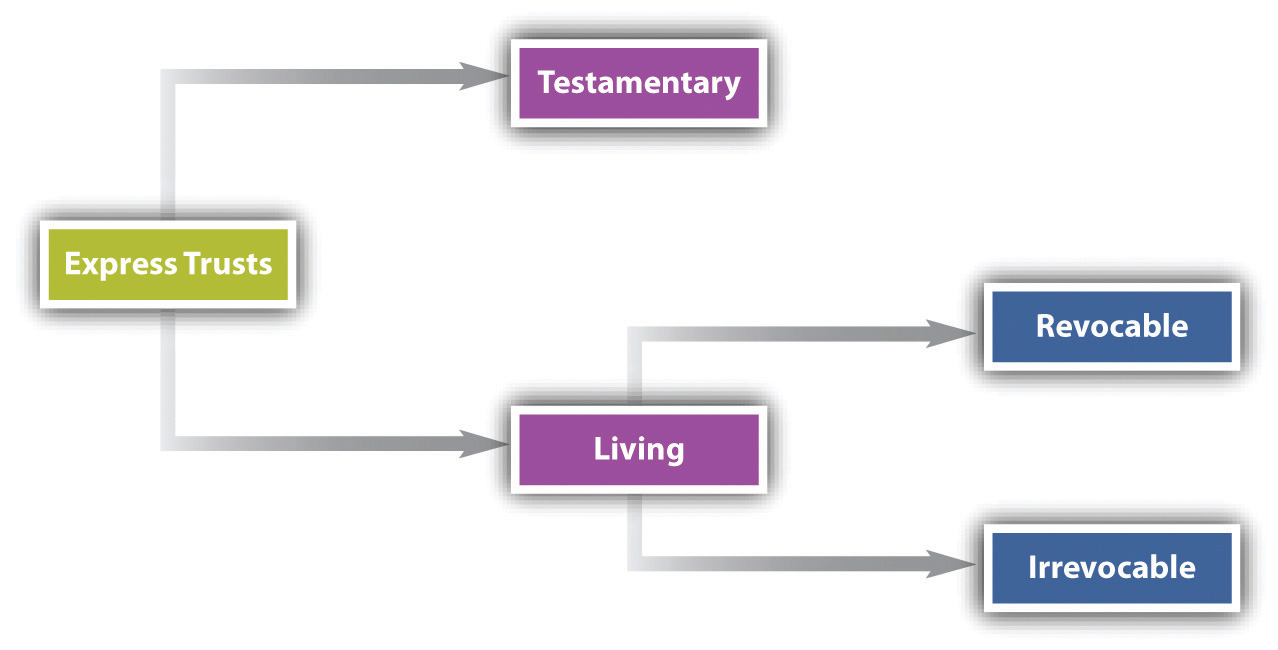

Trusts are divided into two main categories: express and implied. Express trusts include testamentary trustsA trust made during the settlor’s life that takes effect on his death. and inter vivos (or living) trustsA trust that takes effect during the life of the settlor.. The testamentary trust is one created by will. It becomes effective on the testator’s death. The inter vivos trust is one created during the lifetime of the grantor. It can be revocable or irrevocable (see Figure 14.3 "Express Trusts").

Figure 14.3 Express Trusts

A revocable trustA trust that the settlor can terminate at his option. is one that the settlor can terminate at his option. On termination, legal title to the trust assets returns to the settlor. Because the settlor can reassert control over the assets whenever he wishes, the income they generate is taxed to him.

By contrast, an irrevocable trustA trust that the settlor cannot terminate at his option. is permanent, and the settlor may not revoke or modify its terms. All income to the trust must be accumulated in the trust or be paid to the beneficiaries in accordance with the trust agreement. Because income does not go to the settlor, the irrevocable trust has important income tax advantages, even though it means permanent loss of control over the assets (beyond the instructions for its use and disposition that the settlor may lay out in the trust agreement). A hybrid form is the reversionary trust: until the end of a fixed period, the trust is irrevocable and the settlor may not modify its terms, but thereafter the trust assets revert to the settlor. The reversionary trust combines tax advantages with ultimate possession of the assets.

Of the possible types of express trusts, five are worth examining briefly: (1) Totten trusts, (2), blind trusts, (3) Clifford trusts, (4) charitable trusts, and (5) spendthrift trusts. The use of express trusts in business will also be noted.

The Totten trust, which gets its name from a New York case, In re Totten,In re Totten, 71 N.E. 748 (N.Y. 1904). is a tentative trust created when someone deposits funds in a bank as trustee for another person as beneficiary. (Usually, the account will be named in the following form: “Mary, in trust for Ed.”) During the beneficiary’s lifetime, the grantor-depositor may withdraw funds at his discretion or revoke the trust altogether. But if the grantor-depositor dies before the beneficiary and had not revoked the trust, then the beneficiary is entitled to whatever remains in the account at the time of the depositor’s death.

In a blind trust, the grantor transfers assets—usually stocks and bonds—to trustees who hold and manage them for the grantor as beneficiary. The trustees are not permitted to tell the grantor how they are managing the portfolio. The blind trust is used by high government officials who are required by the Ethics in Government Act of 1978 to put their assets in blind trusts or abstain from making decisions that affect any companies in which they have a financial stake. Once the trust is created, the grantor-beneficiary is forbidden from discussing financial matters with the trustees or even to give the trustees advice. All that the grantor-beneficiary sees is a quarterly statement indicating by how much the trust net worth has increased or decreased.

The Clifford trust, named after the settlor in a Supreme Court case, Helvering v. Clifford,Helvering v. Clifford, 309 U.S. 331 (1940). is reversionary: the grantor establishes a trust irrevocable for at least ten years and a day. By so doing, the grantor shifts the tax burden to the beneficiary. So a person in a higher bracket can save considerable money by establishing a Clifford trust to benefit, say, his or her children. The tax savings will apply as long as the income from the trust is not devoted to needs of the children that the grantor is legally required to supply. At the expiration of the express period in the trust, legal title to the res reverts to the grantor. However, the Tax Reform Act of 1986 removed the tax advantages for Clifford trusts established after March 1986. As a result, all income from such trusts is taxed to the grantor. Existing Clifford trusts were not affected by the 1986 tax law.

A charitable trust is one devoted to any public purpose. The definition is broad; it can encompass funds for research to conquer disease, to aid battered wives, to add to museum collections, or to permit a group to proselytize on behalf of a particular political or religious doctrine. The law in all states recognizes the benefits to be derived from encouraging charitable trusts, and states use the cy pres (see press; “as near as possible”) doctrine to further the intent of the grantor. The most common type of trust is the charitable remainder trust. You would donate property—usually intangible property such as stock—in trust to an approved charitable organization, usually one that has tax-exempt 501(c)(3) status from the IRS. The organization serves as trustee during your life and provides you or someone you designate with a specified level of income from the property that you donated. This could be for a number of years or for your lifetime. After your death or the period that you set, the trust ends and the charitable organization owns the assets that were in the trust.

There are important tax reasons why people set up charitable trusts. The trustor gets five years' worth of tax deductions for the value of the assets in the charitable trust. Capital gains are treated favorably, as well: charitable trusts are irrevocable, which means that the person setting up the trust (the “trustor”) permanently gives up control of the assets to the charitable organization. Thus, the charitable organization could sell an asset in the trust that would ordinarily incur significant capital gains taxes, but since the trustor no longer owns the asset, there is no capital gains tax: as a tax-exempt organization, the charity will not pay capital gains, either.

A spendthrift trust is established when the settlor believes that the beneficiary is not to be trusted with whatever rights she might possess to assign the income or assets of the trust. By express provision in a trust instrument, the settlor may ensure that the trustees are legally obligated to pay only income to the beneficiary; no assignment of the assets may be made, either voluntarily by the beneficiary or involuntarily by operation of law. Hence the spendthrift beneficiary cannot gamble away the trust assets nor can they be reached by creditors to pay her gambling (or other) debts.

In addition to their use in estate planning, express trusts are also created for business purposes. The business trust was popular late in the nineteenth century as a way of getting around state limitations on the corporate form and is still used today. By giving their shares to a voting trust, shareholders can ensure that their agreement to vote as a bloc will be carried out. But voting trusts can be dangerous. Agreements that result in price fixing or other restraints of trade violate the antitrust laws; for example, companies are in violation when they act collusively to fix prices by pooling voting stock under a trust agreement, as happened frequently at the turn of the century.

Trusts can be created by courts without any intent by a settlor to do so. For various reasons, a court will declare that particular property is to be held by its owner in trust for someone else. Such trusts are implied trusts and are usually divided into two types: constructive trustsCreated by courts to redress fraud or prevent unjust enrichment. and resulting trustsCreated by courts to give effect to the intent of the parties.. A constructive trust is one created usually to redress a fraud or to prevent unjust enrichment. Suppose you give $1 to an agent to purchase a lottery ticket for you, but the agent buys the ticket in his own name instead and wins $1,000,000, payable into an account in amounts of $50,000 per year for twenty years. Since the agent had violated his fiduciary obligation and unjustly enriched himself, the court would impose a constructive trust on the account, and the agent would find himself holding the funds as trustee for you as beneficiary. By contrast, a resulting trust is one imposed to carry out the supposed intent of the parties. You give an agent $100,000 to purchase a house for you. Title is put in your agent’s name at the closing, although it is clear that since she was paid for her services, you did not intend to give the house to her as a gift. The court would declare that the house was to be held by the agent as trustee for you during the time that it takes to have the title put in your name.

A trust can be created during the life of the settlor of the trust. A named trustee and beneficiary are required, as well as some assets that the trustee will administer. The trustee has a fiduciary duty to administer the trust with the utmost care. Inter vivos trusts can be revocable or irrevocable. Testamentary trusts are, by definition, not revocable, as they take effect on the death of the settlor.