After reading this chapter, you should be able to understand and articulate answers to the following questions:

Under the business model used by TOMS Shoes, a pair of their signature alpargata footwear is donated for every pair sold.

Image courtesy of Parke Ladd, http://www.flickr.com/photos/parke-ladd/5389801209.

In 2002, Blake Mycoskie competed with his sister Paige on The Amazing Race—a reality show where groups of two people with existing relationships engage in a global race to win valuable prizes, with the winner receiving a coveted grand prize. Although Blake’s team finished third in the second season of the show, the experience afforded him the opportunity to visit Argentina, where he returned in 2006 and developed the idea to build a company around the alpargata—a popular style of shoe in that region.

The premise of the company Blake started was a unique one. For every shoe sold, a pair will be given to someone in need. This simple business model was the basis for TOMS Shoes, which has now given away more than one million pairs of shoes to those in need in more than twenty countries worldwide.Oloffson, K. 2010, September 29. In Toms’ Shoes: Start-up copy “one-for-one” model. Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from http://online.wsj.com/article/SB1000142405274870411 6004575522251507063936.html

The rise of TOMS Shoes has inspired other companies that have adopted the “buy-one-give-one” philosophy. For example, the Good Little Company donates a meal for every package purchased.Nicolas, S. 2011, February. The great giveaway. Director, 64, 37–39. This business model has also been successfully applied to selling (and donating) other items such as glasses and books.

The social initiatives that drive TOMS Shoes stand in stark contrast to the criticisms that plagued Nike Corporation, where claims of human rights violations, ranging from the use of sweatshops and child labor to lack of compliance with minimum wage laws, were rampant in the 1990s.McCall, W. 1998. Nike battles backlash from overseas sweatshops. Marketing News, 9, 14. While Nike struggled to win back confidence in buyers that were concerned with their business practices, TOMS social initiatives are a source of excellent publicity in pride in those who purchase their products. As further testament to their popularity, TOMS has engaged in partnerships with Nordstrom, Disney, and Element Skateboards.

Although the idea of social entrepreneurship and the birth of firms such as TOMS Shoes are relatively new, a push toward social initiatives has been the source of debate for executives for decades. Issues that have sparked particularly fierce debate include CEO pay and the role of today’s modern corporation. More than a quarter of a century ago, famed economist Milton Friedman argued, “The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits.” This notion is now being challenged by firms such as TOMS and their entrepreneurial CEO, who argue that serving other stakeholders beyond the owners and shareholders can be a powerful, inspiring, and successful motivation for growing business.

This chapter discusses some of the key issues and decisions relevant to understanding corporate and business ethics. Issues include how to govern large corporations in an effective and ethical manner, what behaviors are considered best practices in regard to corporate social performance, and how different generational perspectives and biases may hold a powerful influence on important decisions. Understanding these issues may provide knowledge that can encourage effective organizational leadership like that of TOMS Shoes and discourage the criticisms of many firms associated with the corporate scandals of the late 1990s and early 2000s.

“You’re fired!” is a commonly used phrase most closely associated with Donald Trump as he dismisses candidates on his reality show, The Apprentice. But who would have the power to utter these words to today’s CEOs, whose paychecks are on par with many of the top celebrities and athletes in the world? This honor belongs to the board of directorsA group of individuals, either elected or appointed, that oversees the activities of an organization or corporation.—a group of individuals that oversees the activities of an organization or corporation.

Potentially firing or hiring a CEO is one of many roles played by the board of directors in their charge to provide effective corporate governanceThe processes, policies, and laws that govern an organization (often corporations) to establish accountability and try to eliminate conflicts of interest associated with the principle-agent problems. for the firm. An effective board plays many roles, ranging from the approval of financial objectives, advising on strategic issues, making the firm aware of relevant laws, and representing stakeholdersIndividuals and groups that have an interest to stake a claim in an organization. who have an interest in the long-term performance of the firm (Figure 10.1 "Board Roles"). Effective boards may help bring prestige and important resources to the organization. For example, General Electric’s board often has included the CEOs of other firms as well as former senators and prestigious academics. Blake Mycoskie of TOMS Shoes was touted as an ideal candidate for an “all-star” board of directors because of his ability to fulfill his company’s mission “to show how together we can create a better tomorrow by taking compassionate action today.”Bunting, C. 2011, February 23. Board of dreams: Fantasy board of directors. Business News Daily. Retrieved from http://www.businessnewsdaily.com/681-board-of-directors-fantasy-picks-small-business.html

The key stakeholder of most corporations is generally agreed to be the shareholders of the company’s stock. Most large, publicly traded firms in the United States are made up of thousands of shareholders. While 5 percent ownership in many ventures may seem modest, this amount is considerable in publicly traded companies where such ownership is generally limited to other companies, and ownership in this amount could result in representation on the board of directors.

The possibility of conflicts of interest is considerable in public corporations. On the one hand, CEOs favor large salaries and job stability, and these desires are often accompanied by a tendency to make decisions that would benefit the firm (and their salaries) in the short term at the expense of decisions considered over a longer time horizon. In contrast, shareholders prefer decisions that will grow the value of their stock in the long term. This separation of interest creates an agency problemThe interest of individuals that act as agents to manage the company may not align with the interest of the firm’s stockholders. wherein the interests of the individuals that manage the company (agents such as the CEO) may not align with the interest of the owners (such as stockholders).

The composition of the board is critical because the dynamics of the board play an important part in resolving the agency problem. However, who exactly should be on the board is an issue that has been subject to fierce debate. CEOs often favor the use of board insidersMembers of the board of directors that are generally employed inside of the organization. who often have intimate knowledge of the firm’s business affairs. In contrast, many institutional investorsOrganizations that invest large sums of money into a broad portfolio of holding, such as banks, retirement funds, mutual funds, and pension funds. such as mutual funds and pension funds that hold large blocks of stock in the firm often prefer significant representation by board outsidersMembers of the board of directors that are generally employed outside of the organization. that provide a fresh, nonbiased perspective concerning a firm’s actions.

One particularly controversial issue in regard to board composition is the potential for CEO dualityWhen the chief executive officer is also the chairman of the board of directors., a situation in which the CEO is also the chairman of the board of directors. This has also been known to create a bitter divide within a corporation.

For example, during the 1990s, The Walt Disney Company was often listed in BusinessWeek’s rankings for having one of the worst boards of directors.Lavelle, L. 2002, October 7. The best and worst boards: How corporate scandals are sparking a revolution in governance. BusinessWeek, 104. In 2005, Disney’s board forced the separation of then CEO (and chairman of the board) Michael Eisner’s dual roles. Eisner retained the role of CEO but later stepped down from Disney entirely. Disney’s story reflects a changing reality that boards are acting with considerably more influence than in previous decades when they were viewed largely as rubber stamps that generally folded to the whims of the CEO.

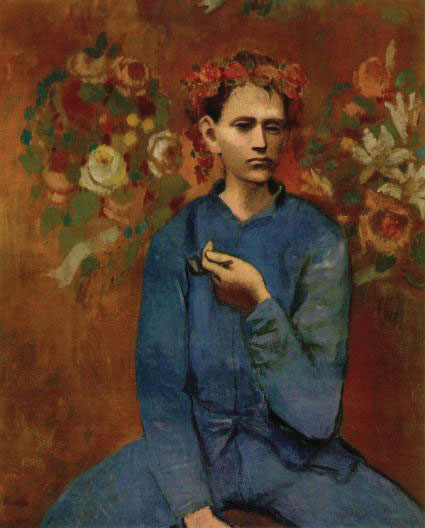

One of the most visible roles of boards of directors is setting CEO pay. The valuation of the human capital associated with the rare talent possessed by some CEOs can be illustrated in a story of an encounter one tourist had with the legendary artist Pablo Picasso. As the story goes, Picasso was once spotted by a woman sketching. Overwhelmed with excitement at the serendipitous meeting, the tourist offered Picasso fair market value if he would render a quick sketch of her image. After completing his commission, she was shocked when he asked for five thousand francs, responding, “But it only took you a few minutes.” Undeterred, Picasso retorted, “No, it took me all my life.”Kay, I. 1999. Don’t devalue human capital. Wall Street Journal—Eastern Edition, 233, A18.

Picasso’s Garçon á la pipe was one of the most expensive works ever sold at more than $100 million.

Image courtesy of Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Gar%C3%A7on_%C3%A0_la_pipe.jpg.

This story illustrates the complexity associated with managing CEO compensation. On the one hand, large corporations must pay competitive wages for the scarce talent that is needed to manage billion-dollar corporations. In addition, like celebrities and sport stars, CEO pay is much more than a function of a day’s work for a day’s pay. CEO compensation is a function of the competitive wages that other corporations would offer for a potential CEO’s services.

On the other hand, boards will face considerable scrutiny from investors if CEO pay is out of line with industry norms. From the year 1980 to 2000, the gap between CEO pay and worker pay grew from 42 to 1 to 475 to 1.Blumenthal, R. G. 2000, September 4. The pay gap between workers and chiefs looks like a chasm. Barron’s, 10. Although efforts to close this gap have been made, as recently as 2008 reports indicate the ratio continues to be as high as 344 to 1, much higher than other countries, where an 80 to 1 ratio is common, or in Japan where the gap is just 16 to 1.Feltman, P. 2009. Experts examine pay disparity, other executive compensation issues. SEC Filings Insight, 15, 1–6. Meanwhile, shareholders need to be aware that research studies have found that CEO pay is positively correlated with the size of firms—the bigger the firm, the higher the CEO’s compensation.Tosi, H. L., Werner, S., Katz., J. P., & Gomez-Mejia, L. R. 2000. How much does performance matter? A meta-analysis of CEO pay studies. Journal of Management, 26, 301–339. Consequently, when a CEO tries to grow a company, such as by acquiring a rival firm, shareholders should question whether such growth is in the company’s best interest or whether it is simply an effort by the CEO to get a pay raise.

In most publicly traded firms, CEO compensation generally includes guaranteed salary, cash bonus, and stock options. But perks provide another valuable source of CEO compensation (Figure 10.2 "CEO Perks"). In addition to the controversy surrounding CEO pay, such perks associated with holding the position of CEO have also come under considerable scrutiny. The term perks, derived from perquisite, refers to special privileges, or rights, as a function of one’s position. CEO perks have ranged in magnitude from the sweet benefit of ice cream for life given to former Ben & Jerry’s CEO Robert Holland, to much more extreme benefits that raise the ears of investors while outraging employees. One such perk was provided to John Thain, who, as former head of NYSE Euronext, received more than $1 million to renovate his office. While such perks may provide powerful incentives to stay with a company, they may result in considerable negative press and serve only to motivate vigilant investors wary of the value of such investments to shop elsewhere.

An old investment cliché encourages individuals to buy low and sell high. When a publicly traded firm loses value, often due to lack of vigilance on the part of the CEO and/or board, a company may become a target of a takeover wherein another firm or set of individuals purchases the company. Generally, the top management team is charged with revitalizing the firm and maximizing its assets.

In some cases, the takeover is in the form of a leveraged buyout (LBO)A company that is purchased through significant debt. in which a publicly traded company is purchased and then taken off the stock market. One of the most famous LBOs was of RJR Nabisco, which inspired the book (and later film) Barbarians at the Gate. LBOs historically are associated with reduction in workforces to streamline processes and decrease costs. The managers who instigate buyouts generally bring a more entrepreneurial mind-set to the firm with the hopes of creating a turnaround from the same fate that made the company an attractive takeover target (recent poor performance).Wright, M., Hoskisson, R. E., & Busenitz, L. W. 2001. Firm rebirth: Buyouts as facilitators of strategic growth and entrepreneurship. Academy of Management Executive, 15, 111–125.

Many takeover attempts increase shareholder value. However, because most takeovers are associated with the dismissal of previous management, the terminology associated with change of ownership has a decidedly negative slant against the acquiring firm’s management team. For example, individuals or firms that hope to conduct a takeover are often referred to as corporate raidersAn individual or firm that purchases stock in another firm with the goal of an eventual takeover.. An unsolicited takeover attempt is often dubbed a hostile takeoverAn attempt to purchase a company that is strongly resisted by the targeted firm’s CEO and/or board., with shark repellentDefenses against takeover attempts. as the potential defenses against such attempts. Although the poor management of a targeted firm is often the reason such businesses are potential takeover targets, when another firm that may be more favorable to existing management enters the picture as an alternative buyer, a white knightA firm that rescues a target firm by offering a friendly takeover as an alternative to a hostile one. is said to have entered the picture (Figure 10.3 "Takeover Terms").

The negative tone of takeover terminology also extends to the potential target firm. CEOs as well as board members are likely to lose their positions after a successful takeover occurs, and a number of antitakeover tactics have been used by boards to deter a corporate raid. For example, many firms are said to pay greenmailAn unfriendly firm forces a target company to repurchase a large block of stock at a premium to thwart a takeover attempt. by repurchasing large blocks of stock at a premium to avoid a potential takeover. Firms may threaten to take a poison pillAn attempt to make the firm’s stock unattractive to raiders by letting shareholders buy stock at a discount, which creates a conversion of equity to debt that makes the firm less attractive. where additional stock is sold to existing shareholders, increasing the shares needed for a viable takeover. Even if the takeover is successful and the previous CEO is dismissed, a golden parachuteA financial package (often including stock options and bonuses worth millions of dollars) given to executives likely to lose their jobs after a takeover. that includes a lucrative financial settlement is likely to provide a soft landing for the ousted executive.

How do ethics evolve over time? Psychologist Lawrence Kohlberg suggests that there are six distinct stages of moral development and that some individuals move further along these stages than others.Kohlberg, L. 1981. Essays in moral development: Vol. 1. The philosophy of moral development. New York, NY: Harper & Row. Kohlberg’s six stages were grouped into three levels: (1) preconventional, (2) conventional, and (3) postconventional (Figure 10.4 "Stages of Moral Development").

The preconventional level of moral reasoning is very egocentric in nature, and moral reasoning is tied to personal concerns. In stage 1, individuals focus on the direct consequences that their actions will have—for example, worry about punishment or getting caught. In stage 2, right or wrong is defined by the reward stage, where a “what’s in it for me” mentality is seen.

In the conventional level of moral reasoning, morality is judged by comparing individuals’ actions with the expectations of society. In stage 3, individuals are conformity driven and act with the goal of fulfilling social roles. Parents that encourage their children to be good boys and girls use this form of moral guidance. In stage 4, the importance of obeying laws, social conventions, or other forms of authority to aid in maintaining a functional society is encouraged. You might witness encouragement under this stage when using a cell phone in a restaurant or when someone is chatting too loudly in a library.

The postconventional level, or principled level, occurs when morality is more than simply following social rules or norms. Stage 5 considers different values and opinions. Thus laws are viewed as social contracts that promote the greatest good for the greatest number of people. Following democratic principles or voting to determine an outcome is common when this stage of reasoning is invoked. In stage 6, moral reasoning is based on universal ethical principles. For example, the golden rule that you should do unto others as you would have them do unto you illustrates one such ethical principle. At this stage, laws are grounded in the idea of right and wrong. Thus individuals follow laws because they are just and not because they will be punished if caught or shunned by society. Consequently, with this stage there is an idea of civil disobedience that individuals have a duty to disobey unjust laws.

In the 1990s and early 2000s, several corporate scandals were revealed in the United States that showed a lack of board vigilance. Perhaps the most famous involves Enron, whose executive antics were documented in the film The Smartest Guys in the Room. Enron used accounting loopholes to hide billions of dollars in failed deals. When their scandal was discovered, top management cashed out millions in stock options while preventing lower-level employees from selling their stock. The collective acts of Enron led many employees to lose all their retirement holdings, and many Enron execs were sentenced to prison.

In response to notable corporate scandals at Enron, WorldCom, Tyco, and other firms, Congress passed sweeping new legislation with the hopes of restoring investor confidence while preventing future scandals (Figure 10.5 "Corporate Scandals"). Signed into law by President George W. Bush in 2002, Sarbanes-OxleyLaw that set new or increased standards for the boards of public US companies and accounting firms. contained eleven aspects that represented some of the most far-reaching reforms since the presidency of Franklin Roosevelt. These reforms create improved standards that affect all publicly traded firms in the United States. The key elements of each aspect of the act are summarized as follows:

The changes that encouraged the creation of Sarbanes-Oxley were so sweeping that comedian Jon Stewart quipped, “Did Wall Street have any rules before this? Can you just shoot a guy for looking at you wrong?” Despite the considerable merits of Sarbanes-Oxley, no legislation can provide a cure-all for corporate scandal (Figure 10.6 "Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (SOX)"). As evidence, the scandal by Bernard Madoff that broke in 2008 represented the largest investor fraud ever committed by an individual. But in contrast to some previous scandals that resulted in relatively minor punishments for their perpetrators, Madoff was sentenced to 150 years in prison.

TOMS Shoes’ commitment to donating a pair of shoes for every shoe sold illustrates the concept of social entrepreneurshipEntrepreneurial actions where both economic and social value creation occur., in which a business is created with a goal of bettering both business and society.Schectman, J. 2010. Good business. Newsweek, 156, 50. Firms such as TOMS exemplify a desire to improve corporate social performance (CSP)The degree to which a firm’s actions honor ethical values that respect individuals, communities, and the natural environment. in which a commitment to individuals, communities, and the natural environment is valued alongside the goal of creating economic value. Although determining the level of a firm’s social responsibility is subjective, this challenge has been addressed in detail by Kinder, Lydenberg and Domini & Co. (KLD), a Boston-based firm that rates firms on a number of stakeholder-related issues with the goal of measuring CSP. KLD conducts ongoing research on social, governance, and environmental performance metrics of publicly traded firms and reports such statistics to institutional investors. The KLD database provides ratings on numerous “strengths” and “concerns” for each firm along a number of dimensions associated with corporate social performance (Figure 10.7 "Measuring Corporate Social Performance"). The results of their assessment are used to develop the Domini social investments fund, which has performed at levels roughly equivalent to the S&P 500.

Assessing the community dimension of CSP is accomplished by assessing community strengths, such as charitable or innovative giving that supports housing, education, or relations with indigenous peoples, as well as charitable efforts worldwide, such as volunteer efforts or in-kind giving. A firm’s CSP rating is lowered when a firm is involved in tax controversies or other negative actions that affect the community, such as plant closings that can negatively affect property values.

Chick-fil-A encourages education through their program that has provided more than $25 million in financial aid to more than twenty-five thousand employees since 1973.

Image courtesy of SanFranAnnie, http://www.flickr.com/photos/sanfranannie/2472244829.

CSP diversity strengths are scored positively when the company is known for promoting women and minorities, especially for board membership and the CEO position. Employment of the disabled and the presence of family benefits such as child or elder care would also result in a positive score by KLD. Diversity concerns include fines or civil penalties in conjunction with an affirmative action or other diversity-related controversy. Lack of representation by women on top management positions—suggesting that a glass ceiling is present at a company—would also negatively impact scoring on this dimension.

The employee relations dimension of CSP gauges potential strengths such as notable union relations, profit sharing and employee stock-option plans, favorable retirement benefits, and positive health and safety programs noted by the US Occupational Health and Safety Administration. Employee relations concerns would be evident in poor union relations, as well as fines paid due to violations of health and safety standards. Substantial workforce reductions as well as concerns about adequate funding of pension plans also warrant concern for this dimension.

The environmental dimension records strengths by examining engagement in recycling, preventing pollution, or using alternative energies. KLD would also score a firm positively if profits derived from environmental products or services were a part of the company’s business. Environmental concerns such as penalties for hazardous waste, air, water, or other violations or actions such as the production of goods or services that could negatively impact the environment would reduce a firm’s CSP score.

Product quality/safety strengths exist when a firm has an established and/or recognized quality program; product quality safety concerns are evident when fines related to product quality and/or safety have been discovered or when a firm has been engaged in questionable marketing practices or paid fines related to antitrust practices or price fixing.

Corporate governance strengths are evident when lower levels of compensation for top management and board members exist, or when the firm owns considerable interest in another company rated favorably by KLD; corporate governance concerns arise when executive compensation is high or when controversies related to accounting, transparency, or political accountability exist.

Thank You for Smoking

Does smoking cigarettes cause lung cancer? Not necessarily, according to a fictitious lobbying group called the Academy of Tobacco Studies (ATS) depicted in Thank You for Smoking (2005). The ATS’s ability to rebuff the critics of smoking was provided by a three-headed monster of disinformation: scientist Erhardt Von Grupten Mundt who had been able to delay finding conclusive evidence of the harms of tobacco for thirty years, lawyers drafted from Ivy League institutions to fight against tobacco legislation, and a spin control division led by the smooth-talking Nick Naylor.

The ATS was a promotional powerhouse. In just one week, the ATS and its spin doctor Naylor distracted the American public by proposing a $50 million campaign against teen smoking, brokered a deal with a major motion picture producer to feature actors and actresses smoking after sex, and bribed a cancer-stricken advertising spokesman to keep quiet. But after the ATS’s transgressions were revealed and cigarette companies were forced to settle a long-standing class-action lawsuit for $246 billion, the ATS was shut down. Although few organizations promote a product as harmful as cigarettes, the lessons offered in Thank You for Smoking have wide application. In particular, the film highlights that choosing between ethical and unethical business practices is not only a moral issue, but it can also determine whether an organization prospers or dies.

Psychologist Kurt Lewin, known as the “founder of social psychology,” created a well-known formula B = ƒ(P,E) that states behavior is a function of the person and their environment. One powerful environmental influence that can be seen in organizations today is based on generational differences. Currently, four generations of workers (traditionalists, baby boomers, Generation X, Generation Y) coexist in many organizations. The different backgrounds and behaviors create challenges for leading these individuals that often have similar shared experiences within their generation but different sets of values, motivations, and preferences in contrast to other generations (Figure 10.8 "Managing Generational Differences"). Effective management of these four different generations involves a realization of their differences and preferred communication styles.Rathman, V. 2011. Four generations at work. Oil & Gas, 109, 10.

The generation born between 1925 and 1946 that fought in World War II and lived through the Great Depression are referred to as traditionalistsThe generation born between 1925 and 1946 that fought in World War II and lived through the Great Depression.. The perseverance of this generation has led journalist Tom Brokaw to dub this group “The Greatest Generation.” As a reflection of a generation that was molded by contributions to World War II, members of this generation value personal communication, loyalty, hierarchy, and are resistant to change. This group now makes up roughly 5 percent of the workforce.

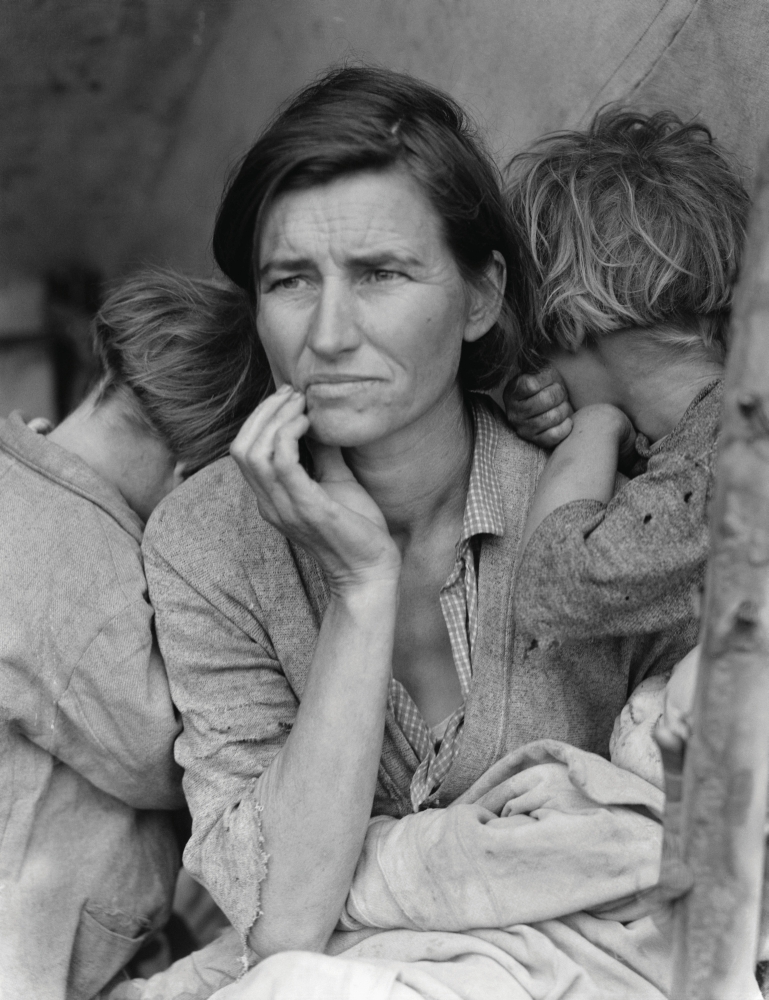

Photographer Dorothea Lange’s photo Migrant Mother, taken in 1936, embodied the struggles of the traditionalist generation that lived during the Great Depression.

Image courtesy of Dorothea Lange, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Lange-MigrantMother02.jpg.

The generation known as baby boomersThe generation born between 1946 and 1964, corresponding with a population “boom” following the end of World War II. was born between 1946 and 1964, corresponding with a population “boom” following the end of World War II. This group witnessed Beatlemania, Vietnam, and the Watergate scandal. College graduates should be aware that this group makes up the majority of the workforce and that boomer managers often view face time as an important contribution to a successful work environment.Fogg, P. 2008, July 18. When generations collide: Colleges try to prevent age-old culture clashes as four distinct groups meet in the workplace. Education Digest, 25–30. In addition, a realization that this generation wants to be included in office activities and values recognition is important to achieving cohesiveness between generations.

Generation XThe generation born between 1965 and 1980; the X symbolizes the unknown nature of this generation.,born between 1965 and 1980, is marked by an X symbolizing their unknown nature. In contrast to the baby boomer’s value on office face time, Gen X members prize flexibility in their jobs and dislike the feeling that they are being micromanaged.Burk, B., Olsen, H., & Messerli, E. 2011, May. Navigating the generation gap in the workplace from the perspective of Generation Y. Parks & Recreation, 35–36. Because of the desire for independence as well as adaptability associated with this generation, you should try to answer the “What’s in it for me?” question to avoid the risk of Gen X members moving on to other employment opportunities.

The generation that followed Generation X is known as Generation YThe generation following Generation X; this group is also known as millennials as well as “The Trophy Generation.” or millennials. This generation is highlighted by positive attributes such as the ability to embrace technology. More than previous generations, this group prizes job and life satisfaction highly, so making the workplace an enjoyable environment is key to managing Generation Y.

Wise members of this generation will also be aware of the negative attributes surrounding them. For example, millennials are associated with their “helicopter” parents who are often too comfortably involved in the lives of their children. For example, such parents have been known to show up to their children’s job orientations, often attempting to interfere with other workplace experiences such as pay and promotion discussions that may be unwelcome by older generations. In addition, this generation is viewed as needing more feedback than previous groups. Finally, the trend toward discouraging some competitive activities among individuals in this age group has led millennials to be dubbed “Trophy Kids” by more cynical writers.

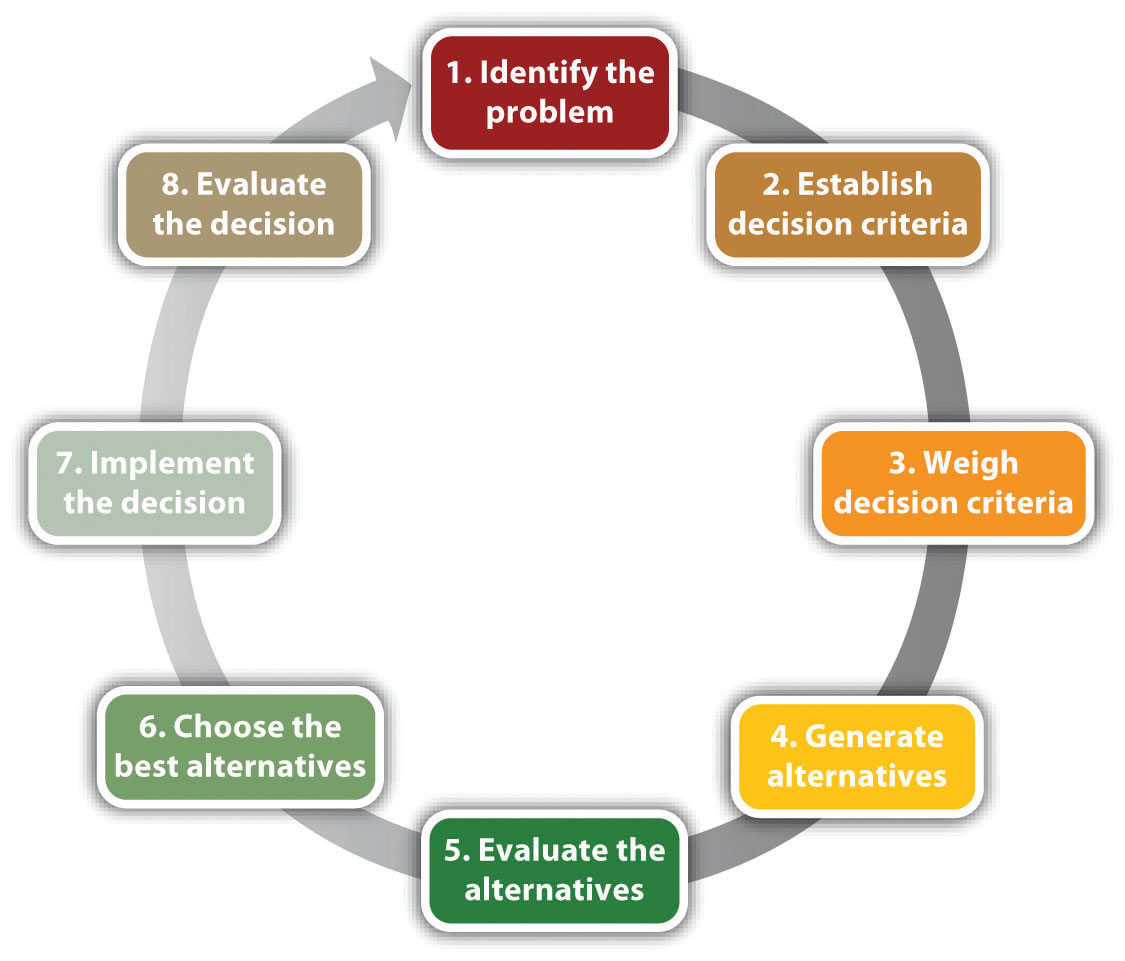

Understanding generational differences can provide valuable insight into the perspectives that shape the behaviors of individuals born at different periods of time. But such knowledge does not answer a more fundamental question of interest to students of strategic management, namely, why do CEOs make bad, unethical, or other questionable decisions with the potential to lead their firms to poor performance or firm failure? Part of the answer lies in the method by which CEOs and other individuals make decisions. Ideally, individuals would make rational decisions for important choices such as buying a car or house, or choosing a career or place to live. The process of rational decision making involves problem identification, establishment and weighing of decision criteria, generation and evaluation of alternatives, selection of the best alternative, decision implementation, and decision evaluation.

Rational Decision-Making Model

Reproduced with permission from [citation redacted per publisher request].

While this model provides valuable insights by providing an ideal approach by which to make decisions, there are several problems with this model when applied to many complex decisions. First, many strategic decisions are not presented in obvious ways, and many CEOs may not be aware their firms are having problems until it’s too late to create a viable solution. Second, rational decision making assumes that options are clear and that a single best solution exists. Third, rational decision making assumes no time or cost constraints. Fourth, rational decision making assumes accurate information is available. Because of these challenges, some have joked that marriage is one of the least rational decisions a person can make because no one can seek out and pursue every possible alternative—even with all the online dating and social networking services in the world.

In reality, decision making is not rational because there are limits on our ability to collect and process information. Because of these limitations, Nobel Prize-winner Herbert Simon argued that we can learn more by examining scenarios where individuals deviate from the ideal. These decision biases provide clues to why individuals such as CEOs make decisions that in retrospect often seem very illogical—especially when they lead to actions that damage the firm and its performance. A number of the most common biases with the potential to affect business decision making are discussed next.

Anchoring and adjustment biasIndividuals react to arbitrary or irrelevant numbers when setting financial or other numerical targets. occurs when individuals react to arbitrary or irrelevant numbers when setting financial or other numerical targets. For example, it is tempting for college graduates to compare their starting salaries at their first career job to the wages earned at jobs used to fund school. Comparisons to siblings, friends, parents, and others with different majors are also very tempting while being generally irrelevant. Instead, research the average starting salary for your background, experience, and other relevant characteristics to get a true gauge. This bias could undermine firm performance if executives make decisions about the potential value of a merger or acquisition by making comparisons to previous deals rather than based on a realistic and careful study of a move’s profit potential (Figure 10.9 "Decision Biases").

The availability biasReadily available information is incorrectly assessed to also be more likely. occurs when more readily available information is incorrectly assessed to also be more likely. For example, research shows that most people think that auto accidents cause more deaths than stomach cancer because auto accidents are reported more in the media than deaths by stomach cancer at a rate of more than 100 to 1. This bias could cause trouble for executives if they focus on readily available information such as their own firm’s performance figures but fail to collect meaningful data on their competitors or industry trends that suggest the need for a potential change in strategic direction.

The idea of “throwing good money after bad” illustrates the bias of escalation of commitmentTo continue on a failing course of action even after it becomes clear that this may be a poor path to follow., when individuals continue on a failing course of action even after it becomes clear that this may be a poor path to follow. This can be regularly seen at Vegas casinos when individuals think the next coin must be more likely to hit the jackpot at the slots. The concept of escalation of commitment was chronicled in the 1990 book Barbarians at the Gate: The Rise and Fall of RJR Nabisco. The book follows the buyout of RJR Nabisco and the bidding war that took place between then CEO of RJR Nabisco F. Ross Johnson and leverage buyout pioneers Henry Kravis and George Roberts. The result of the bidding war was an extremely high sales price of the company that resulted in significant debt for the new owners.

Providing an excellent suggestion to avoid a nonrational escalation of commitment, old school comedian W. C. Fields once advised, “If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again. Then quit. There’s no point being a damn fool about it.”

Image courtesy of Bain News Service, http://wikimediafoundation.org/wiki/File:Wcfields36682u_cropped.jpg

Fundamental attribution errorWhen good outcomes are attributed to personal characteristics (e.g., intelligence), but undesirable outcomes are attributed to external circumstances (e.g., the weather). occurs when good outcomes are attributed to personal characteristics but undesirable outcomes are attributed to external circumstances. Many professors lament a common scenario that, when a student does well on a test, it’s attributed to intelligence. But when a student performs poorly, the result is attributed to an unfair test or lack of adequate teaching based on the professor. In a similar vein, some CEOs are quick to take credit when their firm performs well, but often attribute poor performance to external factors such as the state of the economy.

Hindsight biasMistakes seem obvious after they have already occurred. occurs when mistakes seem obvious after they have already occurred. This bias is often seen when second-guessing failed plays on the football field and is so closely associated with watching National Football League games on Sunday that the phrase Monday morning quarterback is a part of our business and sports vernacular. The decline of firms such as Kodak as victims to the increasing popularity of digital cameras may seem obvious in retrospect. It is easy to overlook the poor quality of early digital technology and to dismiss any notion that Kodak executives had good reason not to view this new technology as a significant competitive threat when digital cameras were first introduced to the market.

Judgments about correlation and causalityTo make inaccurate attributions about the causes of events. can lead to problems when individuals make inaccurate attributions about the causes of events. Three things are necessary to determine cause—or why one element affects another. For example, understanding how marketing spending affects firm performance involves (1) correlation (do sales increase when marketing increases), (2) temporal order (does marketing spending occur before sales increase), and (3) ruling out other potential causes (is something else causing sales to increase: better products, more employees, a recession, a competitor went bankrupt, etc.). The first two items can be tracked easily, but the third is almost impossible to isolate because there are always so many changing factors. In economics, the expression ceteris paribus (all things being equal or constant) is the basis of many economic models; unfortunately, the only constant in reality is change. Of course, just because determining causality is difficult and often inconclusive does not mean that firms should be slow to take strategic action. As the old business saying goes, “We know we always waste half of our marketing budget, we just don’t know which half.”

Misunderstandings about samplingTo draw broad conclusions from small sets of observations instead of more reliable sources of information derived from large, randomly drawn samples. may occur when individuals draw broad conclusions from small sets of observations instead of more reliable sources of information derived from large, randomly drawn samples. Many CEOs have been known to make major financial decisions based on their own instincts rather than on careful number crunching.

Overconfidence biasTo be more confident in your abilities to predict an event than logic suggests is actually possible. occurs when individuals are more confident in their abilities to predict an event than logic suggests is actually possible. For example, two-thirds of lawyers in civil cases believe their side will emerge victorious. But as the famed Yankees player/manager Yogi Berra once noted, “It’s hard to make predictions, especially about the future.” Such overconfidence is common in CEOs that have had success in the past and who often rely on their own intuition rather than on hard data and market research.

RepresentativenessManagers who use stereotypes of similar occurrences when making judgments or decisions. bias occurs when managers use stereotypes of similar occurrences when making judgments or decisions. In some cases, managers may draw from previous experiences to make good decisions when changes in the environment occur. In other cases, representativeness can lead to discriminatory behaviors that may be both unethical and illegal.

FramingThe way information is presented alters the decision an individual will make. bias occurs when the way information is presented alters the decision an individual will make. Poor framing frequently occurs in companies because employees are often reluctant to bring bad news to CEOs. To avoid an unpleasant message, they might be tempted to frame information in a more positive light than reality, knowing that individuals react differently to news that a glass is half empty versus half full.

SatisficingTo settle for the first acceptable alternative instead of seeking the best possible (optimal) decision. occurs when individuals settle for the first acceptable alternative instead of seeking the best possible (optimal) decision. While this bias might actually be desirable when others are waiting behind you at a vending machine, research shows that CEOs commonly satisfice with major decisions such as mergers and takeovers.

This chapter explains the role of boards of directors in the corporate governance of organizations such as large, publicly traded corporations. Wise boards work to manage the agency problem that creates a conflict of interest between top managers such as CEO and other groups with a stake in the firm. When boards fail to do their duties, numerous scandals may ensue. Corporate scandals became so widespread that new legislation such as the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 has been developed with the hope of impeding future actions by executives associated with unethical or illegal behavior. Finally, firms should be aware of generational influences as well as other biases that may lead to poor decisions.