A financial crisisThe functioning of one or more financial markets or intermediaries becomes erratic or ceases altogether. occurs when one or more financial markets or intermediaries cease functioning or function only erratically and inefficiently. A nonsystemic crisisA particular market or intermediary functions erratically or inefficiently. involves only one or a few markets or sectors, like the Savings and Loan Crisis. A systemic crisisThe functioning of all, or nearly all, of the financial system degrades. involves all, or almost all, of the financial system to some extent, as during the Great Depression and the crisis of 2008.

Financial crises are neither new nor unusual. Thousands of crises, including the infamous Tulip Mania and South Sea Company episodes, have rocked financial systems throughout the world in the past five hundred years. Two such crises, in 1764–1768 and 1773, helped lead to the American Revolution.Tim Arango, “The Housing-Bubble and the American Revolution,” New York Times (29 November 2008), WK5. www.nytimes.com/2008/11/30/weekinreview/30arango .html?_r=2&pagewanted=1&ref=weekinreview After its independence, the United States suffered systemic crises in 1792, 1818–1819, 1837–1839, 1857, 1873, 1884, 1893–1895, 1907, 1929–1933, and 2008. Nonsystemic crises have been even more numerous and include the credit crunch of 1966, stock market crashes in 1973–1974 (when the Dow dropped from a 1,039 close on January 12, 1973, to a 788 close on December 5, 1973, to a 578 close on December 6, 1974) and 1987, the failure of Long-Term Capital Management in 1998, the dot-com troubles of 2000, the dramatic events following the terrorist attacks in 2001, and the subprime mortgage debacle of 2007. Sometimes, nonsystemic crises burn out or are brought under control before they spread to other parts of the financial system. Other times, as in 1929 and 2007, nonsystemic crises spread like a wildfire until they threaten to burn the entire system.

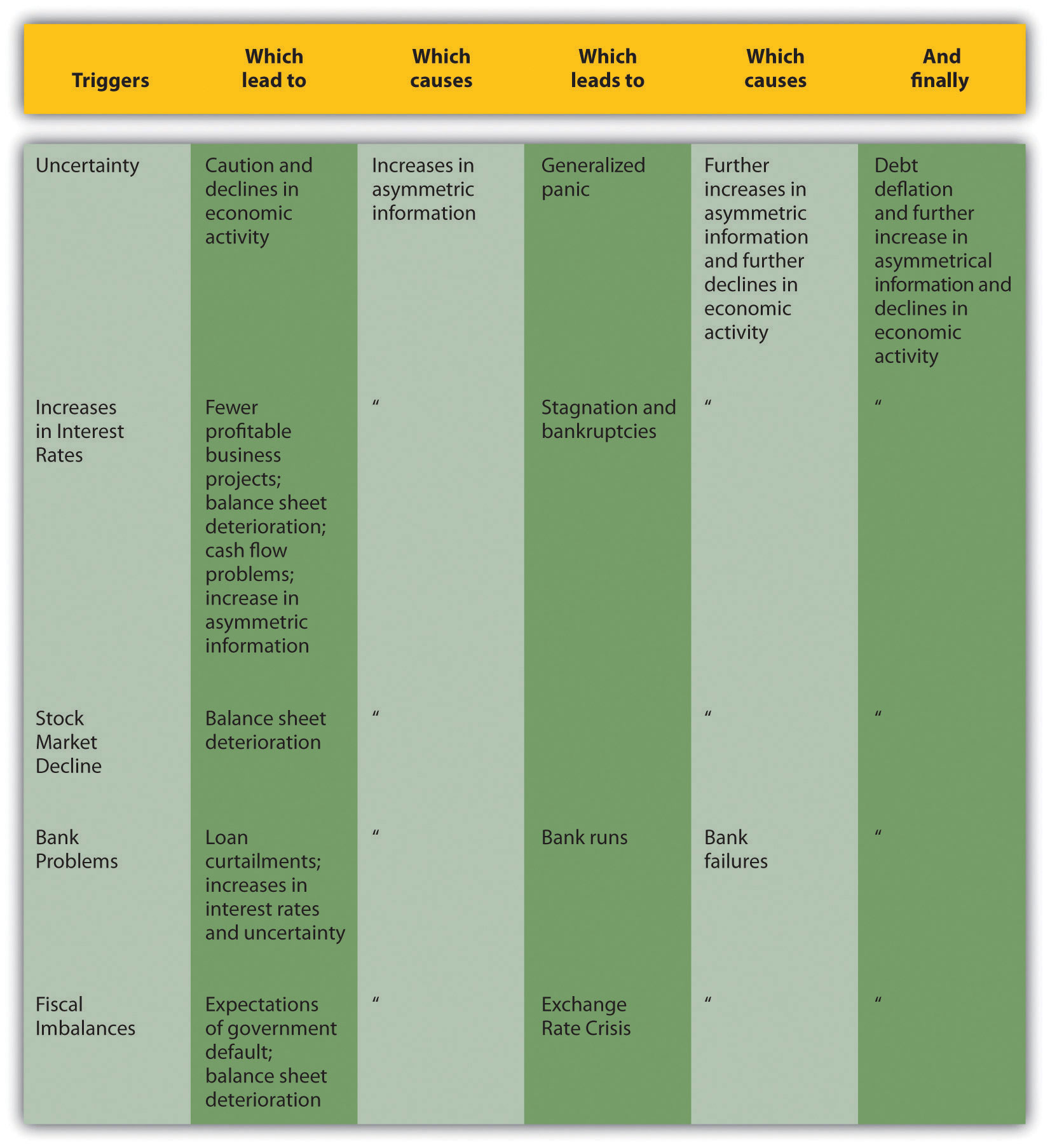

Financial crises can be classified in other ways as well. Some affect banks but not other parts of the financial system. Others mostly involve government debt and/or currency, as in bouts of inflation or rapid depreciation in foreign exchange markets. All types can spread to the other types and even to other nations via balance sheet deterioration and increases in asymmetric information. Five shocksIn economics, sudden, unexpected changes. Shocks usually have adverse consequences, but some can be salutary. The ones discussed here are all bad for the financial system and hence the economy., alone or in combination, have a strong propensity to initiate financial crises.

Increases in uncertainty. When companies cannot plan for the future and when investors feel they cannot estimate future corporate earnings or interest, inflation, or default rates, they tend to play it safe. They hold cash instead of investing in a new factory or equipment. That, of course, reduces aggregate economic activity.

Increases in interest rates. Higher interest rates make business projects less profitable and hence less likely to be completed, a direct blow to gross domestic product (GDP). Also, higher interest rates tend to exacerbate adverse selection by discouraging better borrowers but having little or no effect on the borrowing decisions of riskier companies and individuals. As a result, lenders are saddled with higher default rates in high interest-rate environments. So, contrary to what one would think, high rates reduce their desire to lend. To the extent that businesses own government or other bonds, higher interest rates decrease their net worth, leading to balance sheet deterioration, of which we will soon learn more. Finally, higher interest rates hurt cash flow (receipts minus expenditures), rendering firms more likely to default.

Government fiscal problems. Governments that expend more than they take in via taxes and other revenues have to borrow. The more they borrow, the harder it is for them to service their loans, raising fears of a default, which decreases the market price of their bonds. This hurts the balance sheets of firms that invest in government bonds and may lead to an exchange rate crisis as investors sell assets denominated in the local currency in a flight to safety. Precipitous declines in the value of local currency cause enormous difficulties for firms that have borrowed in foreign currencies, such as dollars, sterling, euro, or yen, because they have to pay more units of local currency than expected for each unit of foreign currency. Many are unable to do so and they default, increasing uncertainty and asymmetric information.

Balance sheet deterioration. Whenever a firm’s balance sheet deteriorates, which is to say, whenever its net worth falls because the value of its assets decreases and/or the value of its liabilities increases, or because stock market participants value the firm less highly, the Cerberus of asymmetric information rears its trio of ugly, fang-infested faces. The company now has less at stake, so it might engage in riskier activities, exacerbating adverse selection. As its net worth declines, moral hazard increases because it grows more likely to default on existing obligations, in turn because it has less at stake. Finally, agency problems become more prevalent as employee bonuses shrink and stock options become valueless. As employees begin to shirk, steal, and look for other work on company time, productivity plummets, and further declines in profitability cannot be far behind. The same negative cycle can also be jump-started by an unanticipated deflation, a decrease in the aggregate price level, because that will make the firm’s liabilities (debts) more onerous in real terms (i.e., adjusted for lower prices).

Banking problems and panics. If anything hurts banks’ balance sheets (like higher than expected default rates on loans they have made), banks will reduce their lending to avoid going bankrupt and/or incurring the wrath of regulators. As we have seen, banks are the most important source of external finance in most countries, so their decision to curtail will negatively affect the economy by reducing the flow of funds between investors and entrepreneurs. If bank balance sheets are hurt badly enough, some may fail. That may trigger the failure of yet more banks for two reasons. First, banks often owe each other considerable sums. If a big bank that owes much too many smaller banks were to fail, it could endanger the solvency of the creditor banks. Second, the failure of a few banks may induce the holders of banks’ monetary liabilities (today mostly deposits, but in the past, as we’ve seen, also bank notes) to run on the bank, to pull their funds out en masse because they can’t tell if their bank is a good one or not. The tragic thing about this is that, because all banks engage in fractional reserve banking (which is to say that no bank keeps enough cash on hand to meet all of its monetary liabilities), runs often become self-fulfilling prophecies, destroying even solvent institutions in a matter of days or even hours. Banking panics and the dead banks they leave in their wake cause uncertainty, higher interest rates, and balance sheet deterioration, all of which, as we’ve seen, hurt aggregate economic activity.

A downward spiral often ensues. Interest rate increases, stock market declines, uncertainty, balance sheet deterioration, and fiscal imbalances all tend to increase asymmetric information. That, in turn, causes economic activity to decline, triggering more crises, including bank panics and/or foreign exchange crises, which increase asymmetric information yet further. Economic activity again declines, perhaps triggering more crises or an unanticipated decline in the price level. That is the point, traditionally, where recessions turn into depressions, unusually long and steep economic downturns.

In early 1792, U.S. banks curtailed their lending. This caused a securities speculator and shyster by the name of William Duer to go bankrupt, owing large sums of money to hundreds of investors. The uncertainty caused by Duer’s sudden failure caused people to panic, inducing them to sell securities, even government bonds, for cash. By midsummer, though, the economy was again humming along nicely. In 1819, banks again curtailed lending, leading to a rash of mercantile failures. People again panicked, this time running on banks (but clutching their government bonds for dear life). Many banks failed and unemployment soared. Economic activity shrank, and it took years to recover. Why did the economy right itself quickly in 1792 but only slowly in 1819?

In 1792, America’s central bank (then the Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton, working in conjunction with the Bank of the United States) acted as a lender of last resort. By adding liquidity to the economy, the central bank calmed fears, reduced uncertainty and asymmetric information, and kept interest rates from spiking and balance sheets from deteriorating further. In 1819, the central bank (with a new Treasury secretary and a new bank, the Second Bank of the United States) crawled under a rock, allowing the initial crisis to increase asymmetric information, reduce aggregate output, and ultimately cause an unexpected debt deflation. Since 1819, the United States has suffered from financial crises on numerous occasions. Sometimes they have ended quickly and quietly, as when Alan Greenspan stymied the stock market crash of 1987. Other times, like after the stock market crash of 1929, the economy did not fare well at all.www.amatecon.com/gd/gdcandc.html

Assuming their vital human capital and market infrastructure have not been destroyed by the depression, economies will eventually reverse themselves after many companies have gone bankrupt, the balance sheets of surviving firms improve, and uncertainty, asymmetric information, and interest rates decrease. It is better for everyone, however, if financial crises can be nipped in the bud before they turn ugly. This is one of the major functions of central banks like the European Central Bank (ECB) and the Fed. Generally, all that the central bank needs to do at the outset of a crisis is to restore confidence, reduce uncertainty, and keep interest rates in line by adding liquidity (cash) to the economy by acting as a lender of last resort, helping out banks and other financial intermediaries with loans and buying government bonds in the open market. Sometimes a bailout, a transfer of wealth from taxpayers to the financial system, becomes necessary. Figure 13.1 "Anatomy of a financial crisis and economic decline" summarizes this discussion of the ill consequences of financial shocks.

But in case you didn’t get the memo, nothing is ever really free. (Well, except for free goods.)en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Free_good When central banks stop financial panics, especially when they do so by bailing out failed companies, they risk creating moral hazard by teaching market participants that they will shield them from risks. That is why some economists, like Allan Meltzer, said “Let ’Em Fail,” in the op-ed pages of the Wall Street JournalJuly 21, 2007. online.wsj.com/article/SB118498744630073854.html when some hedge funds ran into trouble due to the unexpected deterioration of the subprime mortgage market in 2007. Hamilton’s Law (née Bagehot’s Law, which urges lenders of last resort to lend freely at a penalty rate on good security) is powerful precisely because it minimizes moral hazard by providing relief only to the more prudent and solvent firms while allowing the riskiest ones to go under.

Figure 13.1 Anatomy of a financial crisis and economic decline

Note: At any point the downward spiral can be stopped by adequate central bank intervention.

Source: Text.

“While we ridicule ancient superstition we have an implicit faith in the bubbles of banking, and yet it is difficult to discover a greater absurdity, in ascribing omnipotence to bulls, cats and onions, than for a man to carry about a thousand acres of land…in his pocket book.…This gross bubble is practiced every day, even upon the infidelity of avarice itself.…So we see wise and honest Americans, of the nineteenth century, embracing phantoms for realities, and running mad in schemes of refinement, tastes, pleasures, wealth and power, by the soul [sic] aid of this hocus pocus.”—Cause of, and Cure for, Hard Times.books.google.com/books When were these words penned? How do you know?

This was undoubtedly penned during one of the nineteenth century U.S. financial crises mentioned above. Note the negative tone, the allusion to Americans, and the reference to the nineteenth century. In fact, the pamphlet appeared in 1818. For a kick, compare/contrast it to blogs bemoaning the crisis that began in 2007:

http://cartledged.blogspot.com/2007/09/greedy-bastards-club.html

http://www.washingtonmonthly.com/archives/individual/2008_03/013339.php

http://thedefenestrators.blogspot.com/2008/10/death-to-bankers.html

Both systemic and nonsystemic crises damage the real economy by preventing the normal flow of credit from savers to entrepreneurs and other businesses and by making it more difficult or expensive to spread risks. Given the damage financial crises can cause, scholars and policymakers are keenly interested in their causes and consequences. You should be, too.