Allison has a few hours to kill while her flight home is delayed. She loves her job as an analyst for a management consulting firm, but the travel is getting old. As she gazes at the many investment magazines and paperbacks on display and the several screens all tuned to financial news networks and watches people hurriedly checking their stocks on their mobile phones, she begins to think about her own investments. She has been paying her bills, paying back student loans and trying to save some money for a while. Her uncle just died and left her a bequest of $50,000. She is thinking of investing it since she is getting by on her salary and has no immediate plans for this windfall.

Allison is wondering how to get into some serious investing. She is thinking that since so many people seem to be interested in “Wall Street,” there must be money in it. There is no lack of information or advice about investing, but Allison isn’t sure how to get started.

Allison may not realize that there are as many different investment strategies as there are investors. The planning process is similar to planning a budget plan or savings plan. You figure out where you are, where you want to be, and how to get there. One way to get started is to draw up an individual investment policy statement.

Investment policy statementsA structured framework for investment planning based on the investor’s return objectives, risk tolerance, and constraints., outlines of the investor’s goals and constraints, are popular with institutional investors such as pension plans, insurance companies, or nonprofit endowments. Institutional investment decisions typically are made by professional managers operating on instructions from a higher authority, usually a board of directors or trustees. The directors or trustees may approve the investment policy statement and then leave the specific investment decisions up to the professional investment managers. The managers use the policy statement as their guide to the directors’ wishes and concerns.

This idea of a policy statement has been adapted for individual use, providing a helpful, structured framework for investment planning—and thinking. The advantages of drawing up an investment policy to use as a planning framework include the following:

A policy statement is written in two parts. The first part lists your return objectives and risk preferences as an investor. The second part lists your constraints on investment. It sometimes is difficult to reconcile the two parts. That is, you may need to adjust your statement to improve your chances of achieving your return objectives within your risk preferences without violating your constraints.

Defining return objectives is the process of quantifying the required annual return (e.g., 5 percent, 10 percent) necessary to meet your investment goals. If your investment goals are vague (e.g., to “increase wealth”), then any positive return will do. Usually, however, you have some specific goals—for example, to finance a child’s or grandchild’s education, to have a certain amount of wealth at retirement, to buy a sailboat on your fiftieth birthday, and so on.

Once you have defined goals, you must determine when they will happen and how much they will cost, or how much you will have to have invested to make your dreams come true. As explained in Chapter 4 "Evaluating Choices: Time, Risk, and Value", the rate of return that your investments must achieve to reach your goals depends on how much you have to invest to start with, how long you have to invest it, and how much you need to fulfill your goals.

As in Allison’s case, your goals may not be so specific. Your thinking may be more along the lines of “I want my money to grow and not lose value” or “I want the investment to provide a little extra spending money until my salary rises as my career advances.” In that case, your return objective can be calculated based on the role that these funds play in your life: safety net, emergency fund, extra spending money, or nest egg for the future.

However specific (or not) your goals may be, the quantified return objective defines the annual performance that you demand from your investments. Your portfolio can then be structured—you can choose your investments—such that it can be expected to provide that performance.

If your return objective is more than can be achieved given your investment and expected market conditions, then you know to scale down your goals, or perhaps find a different way to fund them. For example, if Allison wanted to stop working in ten years and start her own business, she probably would not be able to achieve this goal solely by investing her $50,000 inheritance, even in a bull (up) market earning higher rates of return.

As you saw in Chapter 10 "Personal Risk Management: Insurance" and Chapter 11 "Personal Risk Management: Retirement and Estate Planning", in investing there is a direct relationship between risk and return, and risk is costly. The nature of these relationships has fascinated and frustrated investors since the origin of capital markets and remains a subject of investigation, exploration, and debate. To invest is to take risk. To invest is to separate yourself from your money through actual distance—you literally give it to someone else—or through time. There is always some risk that what you get back is worth less (or costs more) than what you invested (a loss) or less than what you might have had if you had done something else with your money (opportunity cost). The more risk you are willing to take, the more potential return you can make, but the higher the risk, the more potential losses and opportunity costs you may incur.

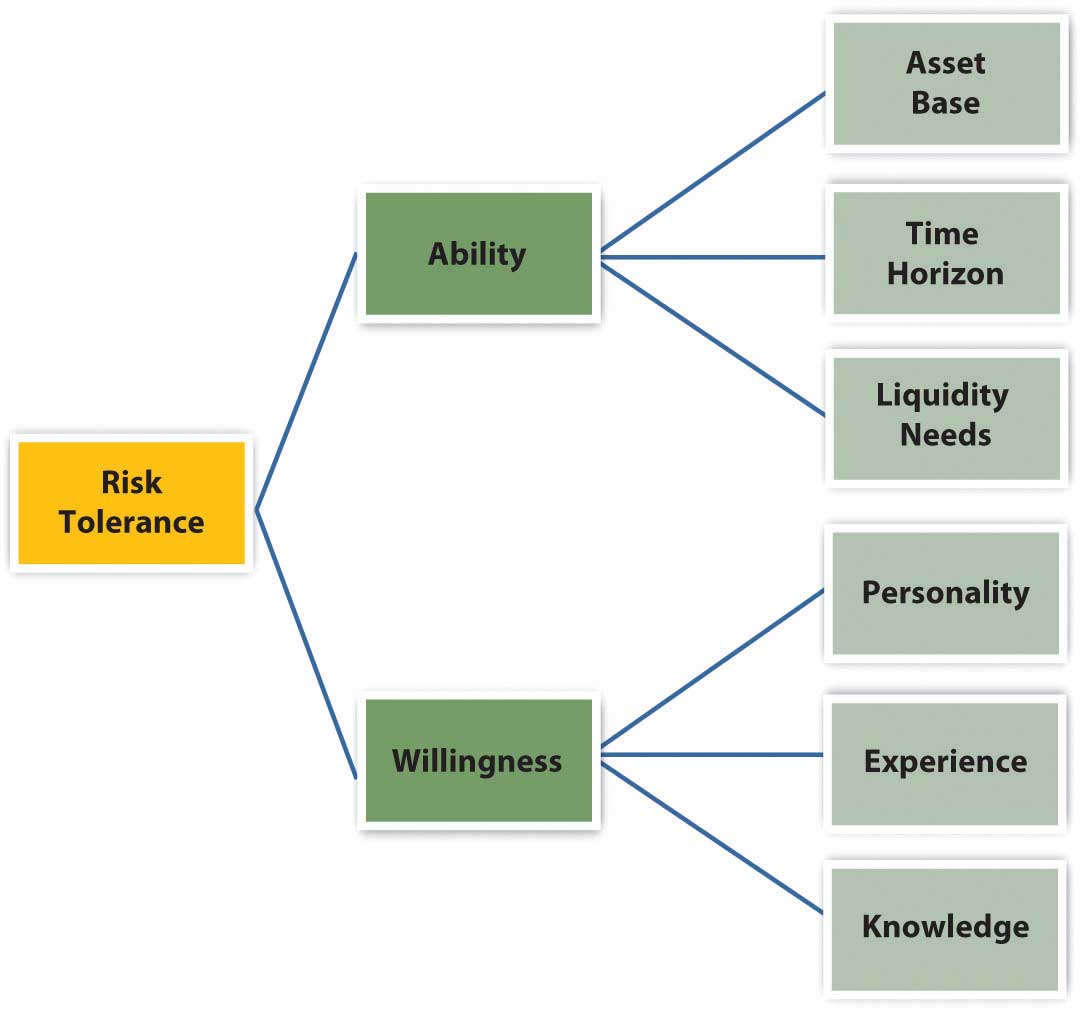

Individuals have different risk tolerances. Your risk toleranceAn investor’s capacity for risk exposure, based on the ability and willingness to assume risk. is your ability and willingness to assume risk. Your ability to assume risk is based on your asset base, your time horizon, and your liquidity needs. In other words, your ability to take investment risks is limited by how much you have to invest, how long you have to invest it, and your need for your portfolio to provide cash—for use rather than reinvestment—in the meantime.

Your willingness to take risk is shaped by your “personality,” your experiences, and your knowledge and education. Attitudes are shaped by life experiences, and attitudes toward risk are no different. Figure 12.7 "Risk Tolerance" shows how your level of risk tolerance develops.

Figure 12.7 Risk Tolerance

Investment advisors may try to gauge your attitude toward risk by having you answer a series of questions on a formal questionnaire or by just talking with you about your investment approach. For example, an investor who says, “It’s more important to me to preserve what I have than to make big gains in the markets,” is relatively risk averseAn investor’s preference to minimize exposure to risk.. The investor who says, “I just want to make a quick profit,” is probably more of a risk seeker.

Once you have determined your return objective and risk tolerance (i.e., what it will take to reach your goals and what you are willing and able to risk to get there) you may have to reconcile the two. You may find that your goals are not realistic unless you are willing to take on more risk. If you are unwilling or unable to take on more risk, you may have to scale down your goals.

Defining constraints is a process of recognizing any limitation that may impede or slow or divert progress toward your goals. The more you can anticipate and include constraints in your planning, the less likely they will throw you off course. Constraints include the following:

Liquidity needs, or the need to use cash, can slow your progress from investing because you have to divert cash from your investment portfolio in order to spend it. In addition you will have ongoing expenses from investing. For example, you will have to use some liquidity to cover your transaction costs such as brokerage fees and management fees. You may also wish to use your portfolio as a source of regular income or to finance asset purchases, such as the down payment on a home or a new car or new appliances.

While these may be happy transactions for you, for your portfolio they are negative events, because they take away value from your investment portfolio. Since your portfolio’s ability to earn return is based on its value, whenever you take away from that value, you are reducing its ability to earn.

Time is another determinant of your portfolio’s earning power. The more time you have to let your investments earn, the more earnings you can amass. Or, the more time you have to reach your goals, the more slowly you can afford to get there, earning less return each year but taking less risk as you do. Your time horizon will depend on your age and life stage and on your goals and their specific liquidity needs.

Tax obligations are another constraint, because paying taxes takes value away from your investments. Investment value may be taxed in many ways (as income tax, capital gains tax, property tax, estate tax, or gift tax) depending on how it is invested, how its returns are earned, and how ownership is transferred if it is bought or sold.

Investors typically want to avoid, defer, or minimize paying taxes, and some investment strategies will do that better than others. In any case, your individual tax liabilities may become a constraint in determining how the portfolio earns to best avoid, defer, or minimize taxes.

Legalities also can be a constraint if the portfolio is not owned by you as an individual investor but by a personal trust or a family foundation. Trusts and foundations have legal constraints defined by their structure.

“Unique circumstances” refer to your individual preferences, beliefs, and values as an investor. For example, some investors believe in socially responsible investing (SRI), so they want their funds to be invested in companies that practice good corporate governance, responsible citizenship, fair trade practices, or environmental stewardship.

Some investors don’t want to finance companies that make objectionable products or by-products or have labor or trade practices reflecting objectionable political views. DivestmentThe sale of an asset to reverse an invested position. is the term for taking money out of investments. Grassroots political movements often include divestiture campaigns, such as student demands that their universities stop investing in companies that do business with nondemocratic or oppressive governments.

Socially responsible investmentAn investment strategy to achieve both ethical and financial goals. is the term for investments based on ideas about products or businesses that are desirable or objectionable. These qualities are in the eye of the beholder, however, and vary among investors. Your beliefs and values are unique to you and to your circumstances in investing and may change over time.

Having mapped out your goals and determined the risks you are willing to take, and having recognized the limitations you must work with, you and/or investment advisors can now choose the best investments. Different advisors may have different suggestions based on your investment policy statement. The process of choosing involves knowing what returns and risks investments have produced in the past, what returns and risks they are likely to have in the future, and how the returns and risks are related—or not—to each other.

The investment policy statement provides a useful framework for investment planning because

Constraints or restrictions to an investment strategy are the investor’s

In collaboration with classmates, conduct an online investigation into socially responsible investing. See the following Web sites:

On the basis of your investigation, outline and discuss the different forms and purposes of SRI. Which form and purpose appeal most to you and why? What investments might you make, and what investments might you specifically avoid, to express your beliefs and values? Do you think investment planning could ever have a role in bringing about social change?