Theories structure and inform sociological research. So, too, does research structure and inform theory. The reciprocal relationship between theory and research often becomes evident to students new to these topics when they consider the relationships between theory and research in inductive and deductive approaches to research. In both cases, theory is crucial. But the relationship between theory and research differs for each approach. Inductive and deductive approaches to research are quite different, but they can also be complementary. Let’s start by looking at each one and how they differ from one another. Then we’ll move on to thinking about how they complement one another.

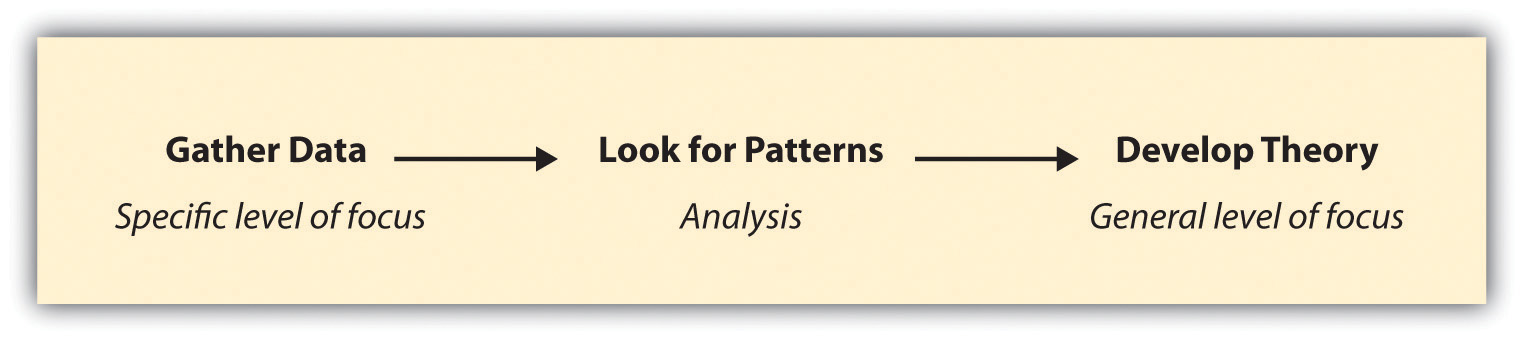

In an inductive approachCollect data, analyze patterns in the data, and then theorize from the data. to research, a researcher begins by collecting data that is relevant to his or her topic of interest. Once a substantial amount of data have been collected, the researcher will then take a breather from data collection, stepping back to get a bird’s eye view of her data. At this stage, the researcher looks for patterns in the data, working to develop a theory that could explain those patterns. Thus when researchers take an inductive approach, they start with a set of observations and then they move from those particular experiences to a more general set of propositions about those experiences. In other words, they move from data to theory, or from the specific to the general. Figure 2.5 "Inductive Research" outlines the steps involved with an inductive approach to research.

Figure 2.5 Inductive Research

There are many good examples of inductive research, but we’ll look at just a few here. One fascinating recent study in which the researchers took an inductive approach was Katherine Allen, Christine Kaestle, and Abbie Goldberg’s study (2011)Allen, K. R., Kaestle, C. E., & Goldberg, A. E. (2011). More than just a punctuation mark: How boys and young men learn about menstruation. Journal of Family Issues, 32, 129–156. of how boys and young men learn about menstruation. To understand this process, Allen and her colleagues analyzed the written narratives of 23 young men in which the men described how they learned about menstruation, what they thought of it when they first learned about it, and what they think of it now. By looking for patterns across all 23 men’s narratives, the researchers were able to develop a general theory of how boys and young men learn about this aspect of girls’ and women’s biology. They conclude that sisters play an important role in boys’ early understanding of menstruation, that menstruation makes boys feel somewhat separated from girls, and that as they enter young adulthood and form romantic relationships, young men develop more mature attitudes about menstruation.

In another inductive study, Kristin Ferguson and colleagues (Ferguson, Kim, & McCoy, 2011)Ferguson, K. M., Kim, M. A., & McCoy, S. (2011). Enhancing empowerment and leadership among homeless youth in agency and community settings: A grounded theory approach. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 28, 1–22. analyzed empirical data to better understand how best to meet the needs of young people who are homeless. The authors analyzed data from focus groups with 20 young people at a homeless shelter. From these data they developed a set of recommendations for those interested in applied interventions that serve homeless youth. The researchers also developed hypotheses for people who might wish to conduct further investigation of the topic. Though Ferguson and her colleagues did not test the hypotheses that they developed from their analysis, their study ends where most deductive investigations begin: with a set of testable hypotheses.

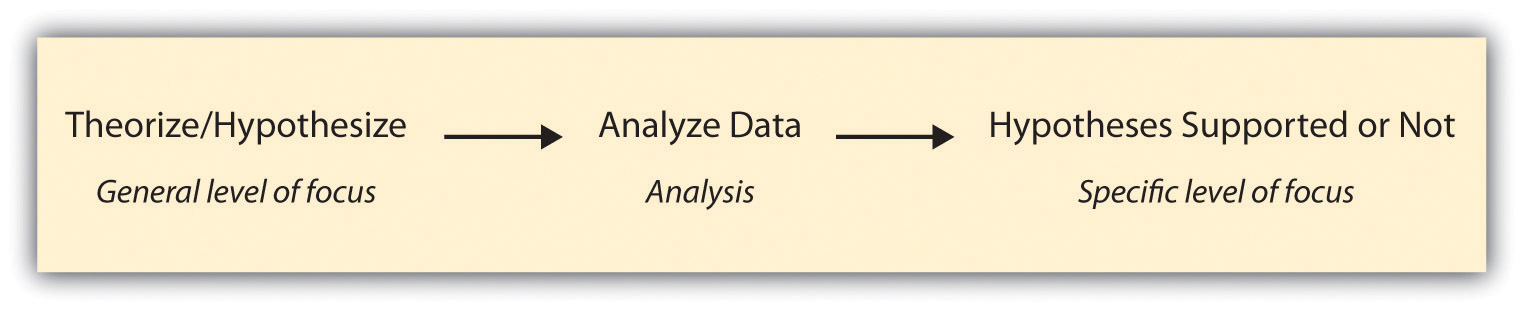

Researchers taking a deductive approachDevelop hypotheses based on some theory or theories, collect data that can be used to test the hypotheses, and assess whether the data collected support the hypotheses. take the steps described earlier for inductive research and reverse their order. They start with a social theory that they find compelling and then test its implications with data. That is, they move from a more general level to a more specific one. A deductive approach to research is the one that people typically associate with scientific investigation. The researcher studies what others have done, reads existing theories of whatever phenomenon he or she is studying, and then tests hypotheses that emerge from those theories. Figure 2.6 "Deductive Research" outlines the steps involved with a deductive approach to research.

Figure 2.6 Deductive Research

While not all researchers follow a deductive approach, as you have seen in the preceding discussion, many do, and there are a number of excellent recent examples of deductive research. We’ll take a look at a couple of those next.

In a study of US law enforcement responses to hate crimes, Ryan King and colleagues (King, Messner, & Baller, 2009)King, R. D., Messner, S. F., & Baller, R. D. (2009). Contemporary hate crimes, law enforcement, and the legacy of racial violence. American Sociological Review, 74, 291–315. hypothesized that law enforcement’s response would be less vigorous in areas of the country that had a stronger history of racial violence. The authors developed their hypothesis from their reading of prior research and theories on the topic. Next, they tested the hypothesis by analyzing data on states’ lynching histories and hate crime responses. Overall, the authors found support for their hypothesis.

In another recent deductive study, Melissa Milkie and Catharine Warner (2011)Milkie, M. A., & Warner, C. H. (2011). Classroom learning environments and the mental health of first grade children. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 52, 4–22. studied the effects of different classroom environments on first graders’ mental health. Based on prior research and theory, Milkie and Warner hypothesized that negative classroom features, such as a lack of basic supplies and even heat, would be associated with emotional and behavioral problems in children. The researchers found support for their hypothesis, demonstrating that policymakers should probably be paying more attention to the mental health outcomes of children’s school experiences, just as they track academic outcomes (American Sociological Association, 2011).The American Sociological Association wrote a press release on Milkie and Warner’s findings: American Sociological Association. (2011). Study: Negative classroom environment adversely affects children’s mental health. Retrieved from http://asanet.org/press/Negative_Classroom_Environment_Adversely_Affects_Childs_Mental_Health.cfm

While inductive and deductive approaches to research seem quite different, they can actually be rather complementary. In some cases, researchers will plan for their research to include multiple components, one inductive and the other deductive. In other cases, a researcher might begin a study with the plan to only conduct either inductive or deductive research, but then he or she discovers along the way that the other approach is needed to help illuminate findings. Here is an example of each such case.

In the case of my collaborative research on sexual harassment, we began the study knowing that we would like to take both a deductive and an inductive approach in our work. We therefore administered a quantitative survey, the responses to which we could analyze in order to test hypotheses, and also conducted qualitative interviews with a number of the survey participants. The survey data were well suited to a deductive approach; we could analyze those data to test hypotheses that were generated based on theories of harassment. The interview data were well suited to an inductive approach; we looked for patterns across the interviews and then tried to make sense of those patterns by theorizing about them.

For one paper (Uggen & Blackstone, 2004),Uggen, C., & Blackstone, A. (2004). Sexual harassment as a gendered expression of power. American Sociological Review, 69, 64–92. we began with a prominent feminist theory of the sexual harassment of adult women and developed a set of hypotheses outlining how we expected the theory to apply in the case of younger women’s and men’s harassment experiences. We then tested our hypotheses by analyzing the survey data. In general, we found support for the theory that posited that the current gender system, in which heteronormative men wield the most power in the workplace, explained workplace sexual harassment—not just of adult women but of younger women and men as well. In a more recent paper (Blackstone, Houle, & Uggen, 2006),Blackstone, A., Houle, J., & Uggen, C. “At the time I thought it was great”: Age, experience, and workers’ perceptions of sexual harassment. Presented at the 2006 meetings of the American Sociological Association. Currently under review. we did not hypothesize about what we might find but instead inductively analyzed the interview data, looking for patterns that might tell us something about how or whether workers’ perceptions of harassment change as they age and gain workplace experience. From this analysis, we determined that workers’ perceptions of harassment did indeed shift as they gained experience and that their later definitions of harassment were more stringent than those they held during adolescence. Overall, our desire to understand young workers’ harassment experiences fully—in terms of their objective workplace experiences, their perceptions of those experiences, and their stories of their experiences—led us to adopt both deductive and inductive approaches in the work.

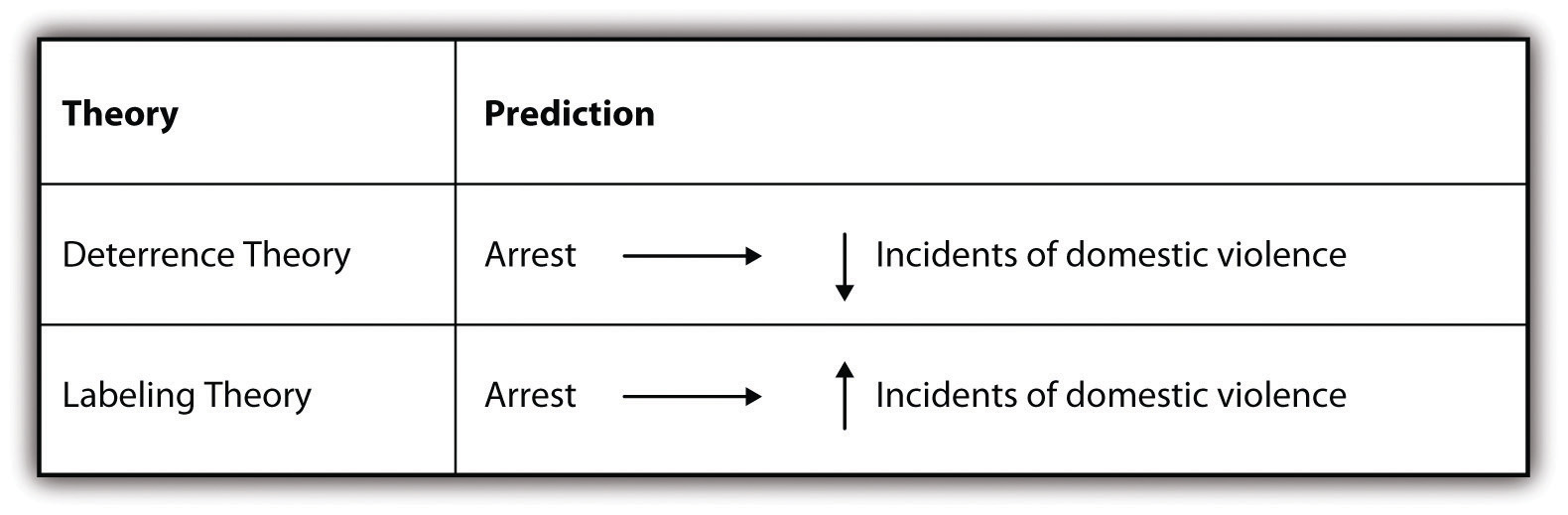

Researchers may not always set out to employ both approaches in their work but sometimes find that their use of one approach leads them to the other. One such example is described eloquently in Russell Schutt’s Investigating the Social World (2006).Schutt, R. K. (2006). Investigating the social world: The process and practice of research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press. As Schutt describes, researchers Lawrence Sherman and Richard Berk (1984)Sherman, L. W., & Berk, R. A. (1984). The specific deterrent effects of arrest for domestic assault. American Sociological Review, 49, 261–272. conducted an experiment to test two competing theories of the effects of punishment on deterring deviance (in this case, domestic violence). Specifically, Sherman and Berk hypothesized that deterrence theory would provide a better explanation of the effects of arresting accused batterers than labeling theory. Deterrence theory predicts that arresting an accused spouse batterer will reduce future incidents of violence. Conversely, labeling theory predicts that arresting accused spouse batterers will increase future incidents. Figure 2.7 "Predicting the Effects of Arrest on Future Spouse Battery" summarizes the two competing theories and the predictions that Sherman and Berk set out to test.

Figure 2.7 Predicting the Effects of Arrest on Future Spouse Battery

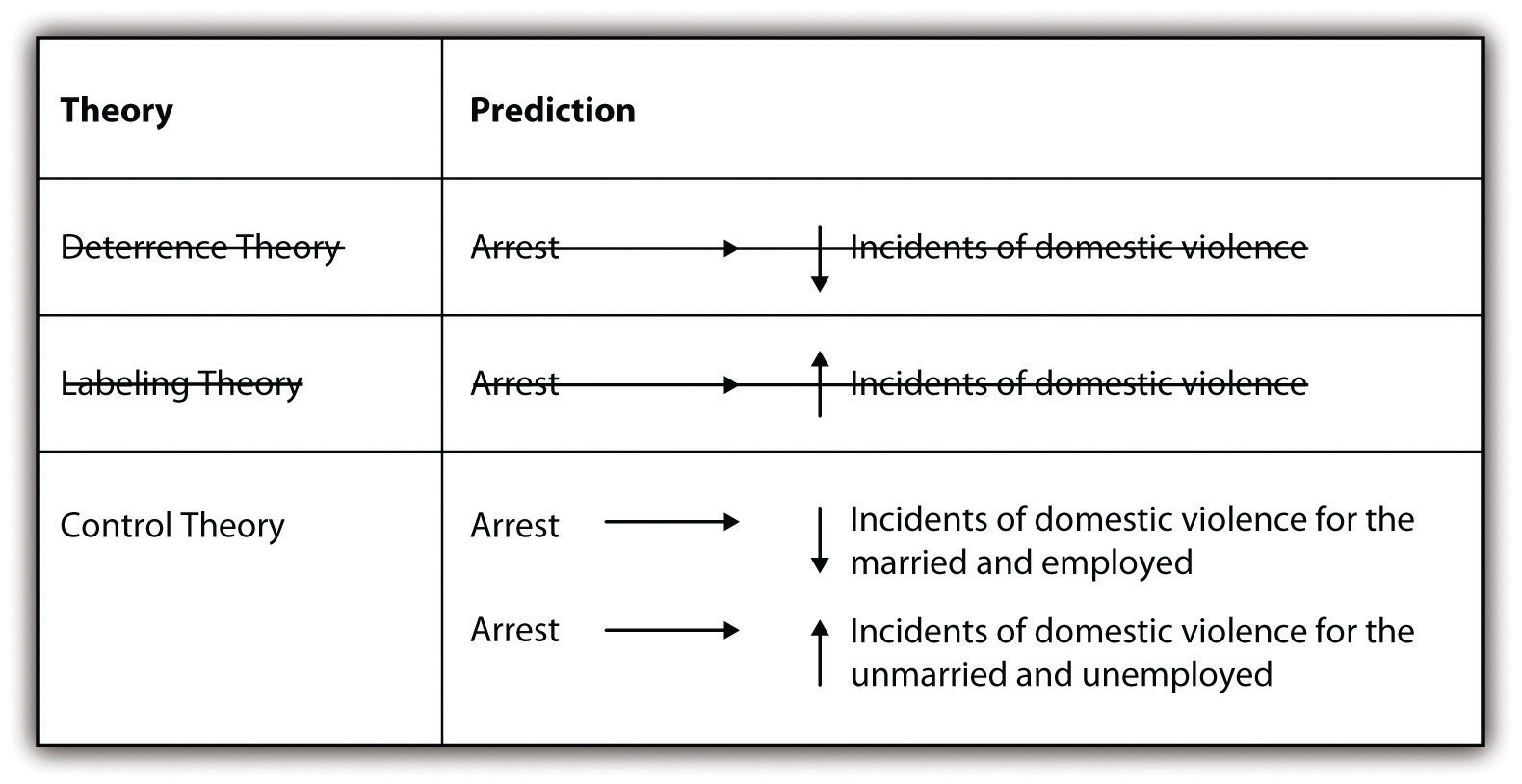

Sherman and Berk found, after conducting an experiment with the help of local police in one city, that arrest did in fact deter future incidents of violence, thus supporting their hypothesis that deterrence theory would better predict the effect of arrest. After conducting this research, they and other researchers went on to conduct similar experimentsThe researchers did what’s called replication. We’ll learn more about replication in Chapter 3 "Research Ethics". in six additional cities (Berk, Campbell, Klap, & Western, 1992; Pate & Hamilton, 1992; Sherman & Smith, 1992).Berk, R., Campbell, A., Klap, R., & Western, B. (1992). The deterrent effect of arrest in incidents of domestic violence: A Bayesian analysis of four field experiments. American Sociological Review, 57, 698–708; Pate, A., & Hamilton, E. (1992). Formal and informal deterrents to domestic violence: The Dade county spouse assault experiment. American Sociological Review, 57, 691–697; Sherman, L., & Smith, D. (1992). Crime, punishment, and stake in conformity: Legal and informal control of domestic violence. American Sociological Review, 57, 680–690. Results from these follow-up studies were mixed. In some cases, arrest deterred future incidents of violence. In other cases, it did not. This left the researchers with new data that they needed to explain. The researchers therefore took an inductive approach in an effort to make sense of their latest empirical observations. The new studies revealed that arrest seemed to have a deterrent effect for those who were married and employed but that it led to increased offenses for those who were unmarried and unemployed. Researchers thus turned to control theory, which predicts that having some stake in conformity through the social ties provided by marriage and employment, as the better explanation.

Figure 2.8 Predicting the Effects of Arrest on Future Spouse Battery: A New Theory

What the Sherman and Berk research, along with the follow-up studies, shows us is that we might start with a deductive approach to research, but then, if confronted by new data that we must make sense of, we may move to an inductive approach. Russell Schutt depicts this process quite nicely in his text, and I’ve adapted his depiction here, in Figure 2.9 "The Research Process: Moving From Deductive to Inductive in a Study of Domestic Violence Recidivism".

For a hilarious example of logic gone awry, check out the following clip from

Monty Python and Holy Grail:

Do the townspeople take an inductive or deductive approach to determine whether the woman in question is a witch? What are some of the different sources of knowledge (recall Chapter 1 "Introduction") they rely on?