The notion of “risk” and its ramifications permeate decision-making processes in each individual’s life and business outcomes and of society itself. Indeed, risk, and how it is managed, are critical aspects of decision making at all levels. We must evaluate profit opportunities in business and in personal terms in terms of the countervailing risks they engender. We must evaluate solutions to problems (global, political, financial, and individual) on a risk-cost, cost-benefit basis rather than on an absolute basis. Because of risk’s all-pervasive presence in our daily lives, you might be surprised that the word “risk” is hard to pin down. For example, what does a businessperson mean when he or she says, “This project should be rejected since it is too risky”? Does it mean that the amount of loss is too high or that the expected value of the loss is high? Is the expected profit on the project too small to justify the consequent risk exposure and the potential losses that might ensue? The reality is that the term “risk” (as used in the English language) is ambiguous in this regard. One might use any of the previous interpretations. Thus, professionals try to use different words to delineate each of these different interpretations. We will discuss possible interpretations in what follows.

We all have a personal intuition about what we mean by the term “risk.” We all use and interpret the word daily. We have all felt the excitement, anticipation, or anxiety of facing a new and uncertain event (the “tingling” aspect of risk taking). Thus, actually giving a single unambiguous definition of what we mean by the notion of “risk” proves to be somewhat difficult. The word “risk” is used in many different contexts. Further, the word takes many different interpretations in these varied contexts. In all cases, however, the notion of risk is inextricably linked to the notion of uncertaintyHaving two potential outcomes for an event or situation.. We provide here a simple definition of uncertainty: Uncertainty is having two potential outcomes for an event or situation.

Certainty refers to knowing something will happen or won’t happen. We may experience no doubt in certain situations. Nonperfect predictability arises in uncertain situations. Uncertainty causes the emotional (or physical) anxiety or excitement felt in uncertain volatile situations. Gambling and participation in extreme sports provide examples. Uncertainty causes us to take precautions. We simply need to avoid certain business activities or involvements that we consider too risky. For example, uncertainty causes mortgage issuers to demand property purchase insurance. The person or corporation occupying the mortgage-funded property must purchase insurance on real estate if we intend to lend them money. If we knew, without a doubt, that something bad was about to occur, we would call it apprehension or dread. It wouldn’t be risk because it would be predictable. Risk will be forever, inextricably linked to uncertainty.

As we all know, certainty is elusive. Uncertainty and risk are pervasive. While we typically associate “risk” with unpleasant or negative events, in reality some risky situations can result in positive outcomes. Take, for example, venture capital investing or entrepreneurial endeavors. Uncertainty about which of several possible outcomes will occur circumscribes the meaning of risk. Uncertainty lies behind the definition of risk.

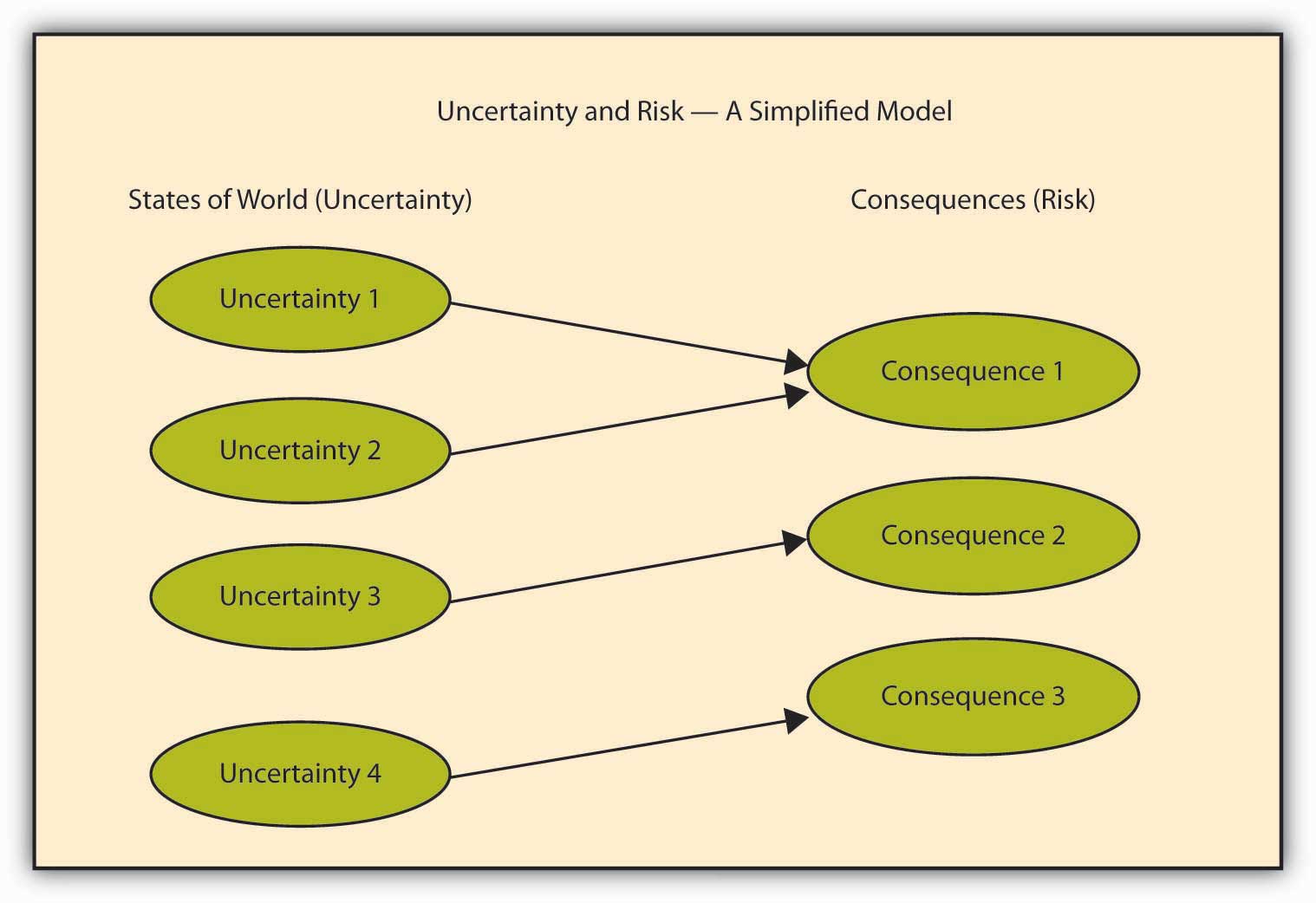

While we link the concept of risk with the notion of uncertainty, risk isn’t synonymous with uncertainty. A person experiencing the flu is not necessarily the same as the virus causing the flu. Risk isn’t the same as the underlying prerequisite of uncertainty. RiskUncertainty about a future outcome, particularly the consequences of a negative outcome. (intuitively and formally) has to do with consequences (both positive and negative); it involves having more than two possible outcomes (uncertainty).See http://www.dhs.gov/dhspublic/. The consequences can be behavioral, psychological, or financial, to name a few. Uncertainty also creates opportunities for gain and the potential for loss. Nevertheless, if no possibility of a negative outcome arises at all, even remotely, then we usually do not refer to the situation as having risk (only uncertainty) as shown in Figure 1.2 "Uncertainty as a Precondition to Risk".

Figure 1.2 Uncertainty as a Precondition to Risk

Table 1.1 Examples of Consequences That Represent Risks

| States of the World —Uncertainty | Consequences—Risk |

|---|---|

| Could or could not get caught driving under the influence of alcohol | Loss of respect by peers (non-numerical); higher car insurance rates or cancellation of auto insurance at the extreme. |

| Potential variety in interest rates over time | Numerical variation in money returned from investment. |

| Various levels of real estate foreclosures | Losses from financial instruments linked to mortgage defaults or some domino effect such as the one that starts this chapter. |

| Smoking cigarettes at various numbers per day | Bad health changes (such as cancer and heart disease) and problems shortening length and quality of life. Inability to contract with life insurance companies at favorable rates. |

| Power plant and automobile emission of greenhouse gasses (CO2) | Global warming, melting of ice caps, rising of oceans, increase in intensity of weather events, displacement of populations; possible extinction or mutations in some populations. |

In general, we widely believe in an a priori (previous to the event) relation between negative risk and profitability. Namely, we believe that in a competitive economic market, we must take on a larger possibility of negative risk if we are to achieve a higher return on an investment. Thus, we must take on a larger possibility of negative risk to receive a favorable rate of return. Every opportunity involves both risk and return.

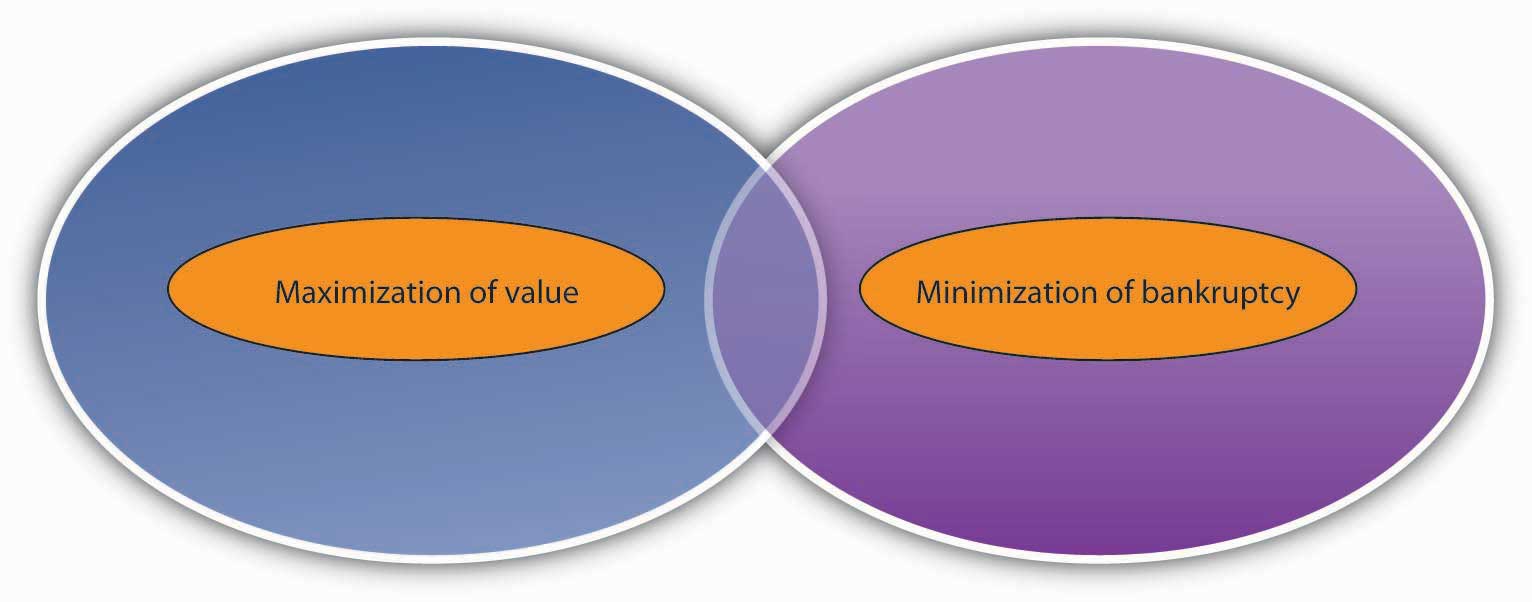

In a world of uncertainty, we regard risk as encompassing the potential provision of both an opportunity for gains as well as the negative prospect for losses. See Figure 1.3 "Roles (Objectives) Underlying the Definition of Risk"—a Venn diagram to help you visualize risk-reward outcomes. For the enterprise and for individuals, risk is a component to be considered within a general objective of maximizing value associated with risk. Alternatively, we wish to minimize the dangers associated with financial collapse or other adverse consequences. The right circle of the figure represents mitigation of adverse consequences like failures. The left circle represents the opportunities of gains when risks are undertaken. As with most Venn diagrams, the two circles intersect to create the set of opportunities for which people take on risk (Circle 1) for reward (Circle 2).

Figure 1.3 Roles (Objectives) Underlying the Definition of Risk

Identify the overlapping area as the set in which we both minimize risk and maximize value.

Figure 1.3 "Roles (Objectives) Underlying the Definition of Risk" will help you conceptualize the impact of risk. Risk permeates the spectrum of decision making from goals of value maximization to goals of insolvency minimization (in game theory terms, maximin). Here we see that we seek to add value from the opportunities presented by uncertainty (and its consequences). The overlapping area shows a tight focus on minimizing the pure losses that might accompany insolvency or bankruptcy. The 2008 financial crisis illustrates the consequences of exploiting opportunities presented by risk; of course, we must also account for the risk and can’t ignore the requisite adverse consequences associated with insolvency. Ignoring risk represents mismanagement of risk in the opportunity-seeking context. It can bring complete calamity and total loss in the pure loss-avoidance context.

We will discuss this trade-off more in depth later in the book. Managing risks associated with the context of minimization of losses has succeeded more than managing risks when we use an objective of value maximization. People model catastrophic consequences that involve risk of loss and insolvency in natural disaster contexts, using complex and innovative statistical techniques. On the other hand, risk management within the context of maximizing value hasn’t yet adequately confronted the potential for catastrophic consequences. The potential for catastrophic human-made financial risk is most dramatically illustrated by the fall 2008 financial crisis. No catastrophic models were considered or developed to counter managers’ value maximization objective, nor were regulators imposing risk constraints on the catastrophic potential of the various financial derivative instruments.

We previously noted that risk is a consequence of uncertainty—it isn’t uncertainty itself. To broadly cover all possible scenarios, we don’t specify exactly what type of “consequence of uncertainty” we were considering as risk. In the popular lexicon of the English language, the “consequence of uncertainty” is that the observed outcome deviates from what we had expected. Consequences, you will recall, can be positive or negative. If the deviation from what was expected is negative, we have the popular notion of risk. “Risk” arises from a negative outcome, which may result from recognizing an uncertain situation.

If we try to get an ex-post (i.e., after the fact) risk measure, we can measure risk as the perceived variability of future outcomes. Actual outcomes may differ from expectations. Such variability of future outcomes corresponds to the economist’s notion of risk. Risk is intimately related to the “surprise an outcome presents.” Various actual quantitative risk measurements provide the topic of Chapter 2 "Risk Measurement and Metrics". Another simple example appears by virtue of our day-to-day expectations. For example, we expect to arrive on time to a particular destination. A variety of obstacles may stop us from actually arriving on time. The obstacles may be within our own behavior or stand externally. However, some uncertainty arises as to whether such an obstacle will happen, resulting in deviation from our previous expectation. As another example, when American Airlines had to ground all their MD-80 planes for government-required inspections, many of us had to cancel our travel plans and couldn’t attend important planned meetings and celebrations. Air travel always carries with it the possibility that we will be grounded, which gives rise to uncertainty. In fact, we experienced this negative event because it was externally imposed upon us. We thus experienced a loss because we deviated from our plans. Other deviations from expectations could include being in an accident rather than a fun outing. The possibility of lower-than-expected (negative) outcomes becomes central to the definition of risk, because so-called losses produce the negative quality associated with not knowing the future. We must then manage the negative consequences of the uncertain future. This is the essence of risk management.

Our perception of risk arises from our perception of and quantification of uncertainty. In scientific settings and in actuarial and financial contexts, risk is usually expressed in terms of the probability of occurrence of adverse events. In other fields, such as political risk assessment, risk may be very qualitative or subjective. This is also the subject of Chapter 2 "Risk Measurement and Metrics".