In the prior chapters, we discussed risks from many aspects. With this chapter we begin the discussion of risk management and its methods that are so vital to businesses and to individuals. Today’s unprecedented global financial crisis following the man-made and natural megacatastrophes underscore the urgency for studying risk management and its tools. Information technology, globalization, and innovation in financial technologies have all led to a term called “enterprise risk management” (ERM). As you learned from the definition of risk in Chapter 1 "The Nature of Risk: Losses and Opportunities" (see Figure 1.2 "Uncertainty as a Precondition to Risk"), ERM includes managing pure opportunity and speculative risks. In this chapter, we discuss how firms use ERM to further their goals. This chapter and Chapter 5 "The Evolution of Risk Management: Enterprise Risk Management" that follows evolve into a more thorough discussion of ERM. While employing new innovations, we should emphasize that the first step to understanding risk management is to learn the basics of the fundamental risk management processes. In a broad sense, they include the processes of identifying, assessing, measuring, and evaluating alternative ways to mitigate risks.

The steps that we follow to identify all of the entity’s risks involve measuring the frequency and severity of losses, as we discussed in Chapter 1 "The Nature of Risk: Losses and Opportunities" and computed in Chapter 2 "Risk Measurement and Metrics". The measurements are essential to create the risk map that profile all the risks identified as important to a business. The risk map is a visual tool used to consider alternatives of the risk management tool set. A risk map forms a grid of frequency and severity intersection points of each identified and measured risk. In this and the next chapter we undertake the task of finding risk management solutions to the risks identified in the risk map. Following is the anthrax story, which occurred right after September 11. It was an unusual risk of high severity and low frequency. The alternative tools for financial solutions to each particular risk are shown in the risk management matrix, which provides fundamental possible solutions to risks with high and low severity and frequency. These possible solutions relate to external and internal conditions and are not absolutes. In times of low insurance prices, the likelihood of using risk transfer is greater than in times of high rates. The risk management process also includes cost-benefit analysis.

The anthrax story was an unusual risk of high severity and low frequency. It illustrates a case of risk management of a scary risk and the dilemma of how best to counteract the risks.

The date staring up from the desk calendar reads June 1, 2002, so why is the Capitol Hill office executive assistant opening Christmas cards? The anthrax scare after September 11, 2001, required these late actions. For six weeks after an anthrax-contaminated letter was received in Senate Majority Leader Tom Daschle’s office, all Capitol Hill mail delivery was stopped. As startling as that sounds, mail delivery is of small concern to the many public and private entities that suffered loss due to the terrorism-related issues of anthrax. The biological agent scare, both real and imagined, created unique issues for businesses and insurers alike since it is the type of poison that kills very easily.

Who is responsible for the clean-up costs related to bioterrorism? Who is liable for the exposure to humans within the contaminated facility? Who covers the cost of a shutdown of a business for decontamination? What is a risk manager to do?

Senator Charles Grassley (R-Iowa), member of the Senate Finance Committee at the time, estimated that the clean-up project cost for the Hart Senate Office Building would exceed $23 million. Manhattan Eye, Ear, and Throat Hospital closed its doors in late October 2001 after a supply-room worker contracted and later died from pulmonary anthrax. The hospital—a small, thirty-bed facility—reopened November 6, 2001, announcing that the anthrax scare closure had cost the facility an estimated $700,000 in revenue.

These examples illustrate the necessity of holistic risk management and the effective use of risk mapping to identify any possible risk, even those that may remotely affect the firm. Even if their companies aren’t being directly targeted, risk managers must incorporate disaster management plans to deal with indirect atrocities that slow or abort the firms’ operations. For example, an import/export business must protect against extended halts in overseas commercial air traffic. A mail-order-catalog retailer must protect against long-term mail delays. Evacuation of a workplace for employees due to mold infestation or biochemical exposure must now be added to disaster recovery plans that are part of loss-control programs. Risk managers take responsibility for such programs.

After a temporary closure, reopened facilities still give cause for concern. Staffers at the Hart Senate Office Building got the green light to return to work on January 22, 2002, after the anthrax remediation process was completed. Immediately, staffers began reporting illnesses. By March, 255 of the building’s employees had complained of symptoms that included headaches, rashes, and eye or throat irritation, possibly from the chemicals used to kill the anthrax. Was the decision to reopen the facility too hasty?

Sources: “U.S. Lawmakers Complain About Old Mail After Anthrax Scare.” Dow Jones Newswires, 8 May 2002; David Pilla, “Anthrax Scare Raises New Liability Issues for Insurers,” A.M. Best Newswire, October 16, 2001; Sheila R. Cherry, “Health Questions Linger at Hart,” Insight on the News, April 15, 2002, p.16; Cinda Becker, “N.Y. Hospital Reopens; Anthrax Scare Costs Facility $700,000,” Modern Healthcare, 12 November 2001, p. 8; Sheila R. Cherry, “Health Questions Linger at Hart,” Insight on the News, April 15, 2002, p. 16(2).

Today’s risk managers explore all risks together and consider correlations between risks and their management. Some risks interact positively with other risks, and the occurrence of one can trigger the other—flood can cause fires or an earthquake that destroys a supplier can interrupt business in another side of the country. As we discussed in Chapter 1 "The Nature of Risk: Losses and Opportunities", economic systemic risks can impact many facets of the corporations, as is the current state of the world during the financial crisis of 2008.

In our technological and information age, every person involved in finding solutions to lower the adverse impact of risks uses risk management information systems (RMIS), which are data bases that provide information with which to compute the frequency and severity, explore difficult-to-identify risks, and provide forecasts and cost-benefits analyses.

This chapter therefore includes the following:

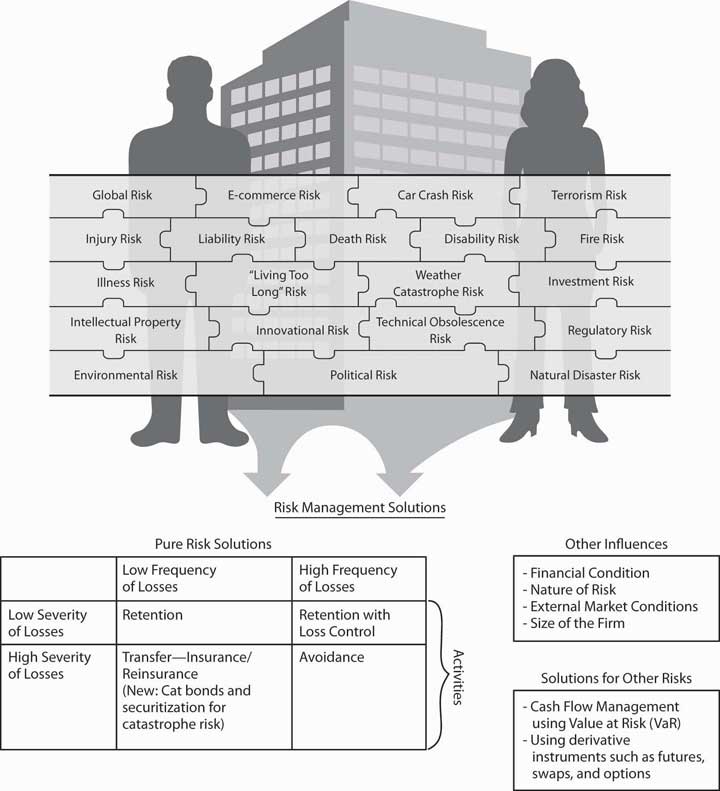

Now that we understand the notion and measurement of risks from Chapter 1 "The Nature of Risk: Losses and Opportunities" and Chapter 2 "Risk Measurement and Metrics", and the attitudes toward risk in Chapter 3 "Risk Attitudes: Expected Utility Theory and Demand for Hedging", we are ready to begin learning about the actual process of risk management. Within the goals of the firm discussed in Chapter 1 "The Nature of Risk: Losses and Opportunities", we now delve into how risk managers conduct their jobs and what they need to know about the marketplace to succeed in reducing and eliminating risks. Holistic risk management is connected to our complete package of risks shown in Figure 4.1 "Links between the Holistic Risk Picture and the Risk Management Alternative Solutions". To complete the puzzle, we have to

Risk management decisions depend on the nature of the identified risks, the forecasted frequency and severity of losses, cost-benefit analysis, and using the risk management matrix in context of external market conditions. As you will see later in this chapter, risk managers may decide to transfer the risk to insurance companies. In such cases, final decisions can’t be separated from the market conditions at the time of purchase. Therefore, we must understand the nature of underwriting cycles, which are the business cycles of the insurance industry when insurance processes increase and fall (explained in Chapter 6 "The Insurance Solution and Institutions"). When insurance prices are high, risk management decisions differ from those made during times of low insurance prices. Since insurance prices are cyclical, different decisions are called for at different times for the same assessed risks.

Risk managers also need to understand the nature of insurance well enough to be aware of which risks are uninsurable. Overall, in this Links section, shown in Figure 4.1 "Links between the Holistic Risk Picture and the Risk Management Alternative Solutions", we can complete our puzzle only when we have mitigated all risks in a smart risk management process.

Figure 4.1 Links between the Holistic Risk Picture and the Risk Management Alternative Solutions