By this point, you have gained an understanding of the life cycle risks associated with mortality, longevity, and health/disability. You have learned about the social insurance programs such as Social Security and Medicare that help counter these risks. We have delved into life, health, and disability insurance products in Chapter 19 "Mortality Risk Management: Individual Life Insurance and Group Life Insurance" and Chapter 22 "Employment and Individual Health Risk Management" and discussed pensions in Chapter 21 "Employment-Based and Individual Longevity Risk Management". The availability and features of these products in group (employer-sponsored) or individual arrangements were also discussed. On the property/casualty side, we covered all the risks confronted by families and enterprises. We discussed the solutions using insurance for the home, automobile, and liability risks. Thus, you now have the tools needed to complete the holistic risk puzzle and the steps representing each layer of the risk management pyramid, from society on up to you as an individual.

With that said, this chapter is a departure from most, but it is vitally important. Our final lesson focuses on applying your knowledge and skills in the complete holistic risk management picture. In other words, you will now learn how to use your new tools. Practical case studies featuring hypothetical families and companies—some designed by fellow students—are utilized to fulfill this objective. The situations posed by these cases are ones that you may encounter in the roles you serve throughout your life, and they incorporate the insurance products and risk management techniques discussed throughout this text.

We begin first with a sample family risk management portfolio involving home, auto, life, health, and disability insurance coverage and planning for retirement. This case is for the personal needs of families. The second case focuses on the employer’s provided employee benefits package. It is designed as the benefits handbook of a hypothetical employer who provides more benefit options than current practices. In the last case, we broaden our understanding of enterprise risk management (covered in Part I of the text) by exploring the concept of alternative risk financing and the challenges faced by a risk manager in selecting among insurance products for commercial risk management needs.

At the conclusion of this chapter, your knowledge of risk management concepts will be reinforced and expanded. The chapter is structured as follows:

To understand the spectrum of personal losses to the families, we introduce two hypothetical families who were directly affected by the World Trade Center catastrophe. The families are those of Allen Zang, who worked as a bond trader in the South Tower of the World Trade Center, and his high school friend Mike Shelling, a graduate student who visited Allen on the way to a job interview. Both Mike and Allen were thirty-four years old and married. Mike had a six-year-old boy and Allen had three young girls.

Figure 23.1 Structure of Insurance Coverages

Both Allen and Mike were among the casualties of the attack on the World Trade Center. But their eligibility for benefits was considerably different because Mike was not employed at the time. In the analysis of the losses or benefits paid to each family, we will first evaluate the benefits available under the social insurance programs mandated in the United States and in New York. Second, we will evaluate the benefits available under the group insurance programs and pensions provided by employers. Third, we will evaluate the private insurance programs purchased by the families (as shown in Figure 23.1 "Structure of Insurance Coverages"). We will also evaluate the ways that families might attempt to collect benefits from negligent parties who may have contributed to the losses.

Recall from Chapter 18 "Social Security" that social insurance programs include Social Security, workers’ compensation, and unemployment compensation insurance (and, in a few states, state-provided disability insurance). In the United States, these programs are intended to protect members of the work force and are not based on need. The best-known aspect of Social Security is the mandatory plan for retirement (so-called old-age benefits). But the program also includes disability benefits; survivors’ benefits; and Medicare parts A, B, C, and D.

Table 23.1 "Benefits for Two Hypothetical Losses of Lives" shows the benefits available to each of the families. It is important to note that both Mike and Allen were employed for at least ten years (forty quarters). Therefore, they were fully insured for Social Security benefits, and their families were eligible to receive survivors’ benefits under Social Security. Each family received the allotted $255 burial benefit. Also, because both had young children, the families were eligible for a portion of the fathers’ Primary Insurance Amount (PIA). The Social Security Administration provided the benefits immediately without official death certificates, as described by Commissioner Larry Massanari in his report to the House Committee on Ways and Means, Subcommittee on Social Security.Social Security Testimony Before Congress, “House Committee on Ways and Means, Subcommittee on Social Security (Shaw) on SSA’s Response to the Terrorist Attacks of September 11, Larry Massanari, Commissioner,” http://www.ssa.gov/legislation/testimony_110101.html (accessed April 16, 2009).

You learned in Chapter 16 "Risks Related to the Job: Workers’ Compensation and Unemployment Compensation" that workers’ compensation provides medical coverage, disability income, rehabilitation, and survivors’ income (death benefits). Benefits are available only if the injury or death occurred on the job or as a result of the job. Because Allen was at the office at the time of his death, his family was eligible to receive survivors’ benefits from the workers’ compensation carrier of the employer.

Table 23.1 Benefits for Two Hypothetical Losses of Lives

| Mike’s Family | Allen’s Family | |

|---|---|---|

| Social insurance | ||

| Death benefits (survivors’ benefits) from Social Security | Yes | Yes |

| Workers’ compensation | No | Yes |

| State disability benefits | No | No |

| Unemployment compensation | No | No |

| Employee benefits (group insurance) | ||

| Group life | No | Yes |

| Group disability | No | Yes |

| Group medical | No | Yes (COBRA) |

| Pensions and 401(k) | Yes (former employers) | Yes |

| Personal insurance | ||

| Individual life policy | Yes | No |

The New York Workers’ Compensation Statute states, “If the worker dies from a compensable injury, the surviving spouse and/or minor children, and lacking such, other dependents as defined by law, are entitled to weekly cash benefits. The amount is equal to two-thirds of the deceased worker’s average weekly wage for the year before the accident. The weekly compensation may not exceed the weekly maximum, despite the number of dependents. If there are no surviving children, spouse, grandchildren, grandparents, brothers, or sisters entitled to compensation, the surviving parents or the estate of the deceased worker may be entitled to payment of a sum of $50,000. Funeral expenses may also be paid, up to $6,000 in Metropolitan New York counties; up to $5,000 in all others.”

The maximum benefit at the time of the catastrophe was $400 per week, less any Social Security benefits, for lifetime or until remarriage.Daniel Hays, “Workers’ Compensation Losses Might Top $1 Billion,” National Underwriter, Property & Casualty/Risk & Benefits Management Edition, September 2001, 10; See also New York State Workers’ Compensation Board at http://www.wcb.state.ny.us/ (accessed April 16, 2009). Thus, Allen’s family received the workers’ compensation benefits minus the Social Security amount. Recall from Chapter 16 "Risks Related to the Job: Workers’ Compensation and Unemployment Compensation" that under the workers’ compensation system, the employee’s family gives up the right to sue the employer. Allen’s family could not sue his employer, but Mike’s family, not having received workers’ compensation benefits, may believe that Allen’s employer was negligent in not providing a safe place for a visitor and may sue under the employer’s general liability coverage.

In Mike’s case, the New York Disability Benefits program did not apply because the program does not include death benefits for “non-job-injury.” If Mike were disabled rather than killed, this state program would have paid him disability benefits. Of course, unemployment compensation does not apply here either. However, it would apply to all workers who lost their jobs involuntarily as a result of a catastrophe.

Because Allen was employed at the time, his family was also eligible to receive group benefits provided by his employer (as covered in Chapter 20 "Employment-Based Risk Management (General)", Chapter 21 "Employment-Based and Individual Longevity Risk Management", and Chapter 22 "Employment and Individual Health Risk Management"). Many employers offer group life and disability coverage, medical insurance, and some types of pension plans or 401(k) tax-free retirement investment accounts. Allen’s employer gave twice the annual salary for basic group term life insurance and twice the annual salary for accidental death and dismemberment (AD&D). The family received from the insurer death benefits in an amount equal to four times Allen’s annual salary, free from income tax (see Chapter 19 "Mortality Risk Management: Individual Life Insurance and Group Life Insurance" and Chapter 21 "Employment-Based and Individual Longevity Risk Management"). Allen earned $100,000 annually; therefore, the total death benefits were $400,000, tax-free.

Allen also elected to be covered by his employer’s group short-term disability (STD) and long-term disability (LTD) plans. Those plans included supplemental provisions giving a small amount of death benefits. In the case of Allen, the amount was $30,000. In addition, his employer provided a defined contribution plan, and the accumulated account balance was available to his beneficiary. The accumulated amount in Allen’s 401(k) account was also available to his beneficiary.

Mike’s family could not take advantage of group benefits because he was not employed. Therefore, no group life or group STD and LTD were available to Mike’s family. However, his pension accounts from former employers and any individual retirement accounts (IRAs) were available to his beneficiary.

Survivors’ medical insurance was a major concern. Allen’s wife did not work and the family had medical coverage from Allen’s employer. Allen’s wife decided to continue the health coverage the family had from her husband’s employer under the Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (COBRA) of 1986. The law provided for continuation of health insurance up to 36 months to the wife as a widow for the whole cost of the coverage (both the employee and the employer’s cost) plus 2 percent (as covered in Chapter 22 "Employment and Individual Health Risk Management").

For Mike’s family, the situation was different because Mike was in graduate school. His wife covered the family under her employer’s health coverage. She simply continued this coverage.

The third layer of available coverage is personal insurance programs. Here, the families’ personal risk management comes into play. When Mike decided to return to school, he and his wife consulted with a reputable financial planner who helped them in their risk management and financial planning. Mike had made a series of successful career moves. In his last senior position at an Internet start-up company, he was able to cash in his stock options and create a sizeable investment account for his family. Also, just before beginning graduate school, Mike purchased a $1 million life insurance policy on his life and $500,000 on his wife’s life. They decided to purchase a twenty-year level term life rather than a universal life policy (for details, refer to Chapter 19 "Mortality Risk Management: Individual Life Insurance and Group Life Insurance") because they wanted to invest some of their money in a new home and a vacation home in Fire Island (off Long Island, New York).

The amount of insurance Mike bought for his wife was lower because she already had sizeable group life coverage under her employer’s group life insurance package. Subsequent to Mike’s death, his wife received the $1 million in death benefits within three weeks. Despite not having a death certificate, she was able to show evidence that her husband was at the World Trade Center at the time. She had a recording on her voice mail at work from Mike telling her that he was going to try to run down the stairs. The message was interrupted by the sound of the building collapsing. Thus, Mike’s beneficiaries, his wife and son, received the $1 million life insurance and the Social Security benefits available. Because the family had sizeable collateral resources (non–federal government sources), they were eligible for less than the maximum amount of the Federal Relief Fund created for the victims’ families.

Allen’s family had not undertaken the comprehensive financial planning that Mike and his family had. He did not have additional life insurance policies, even though he planned to get to it “one of these days.” His family’s benefits were provided by his social insurance coverages and by his employer. The family was also eligible for the relief fund established by the federal government, less collateral resources.

To see how the catastrophe affected nearby businesses, we will examine a hypothetical department store called Worlding. In our scenario, Worlding is a very popular discount store, specializing in name-brand clothing, housewares, cosmetics, and linens. Four stories tall, it is located in the heart of the New York financial district just across from the World Trade Center. At 9:00 A.M. on September 11, 2001, the store had just opened its doors. At any time, shoppers would have to fight crowds in the store to get to the bargains. The morning of September 11 was no different. When American Airlines Flight 11 struck the North Tower, a murmur spread throughout the store and the customers started to run outside to see what happened. As they were looking up, they saw United Airlines Flight 175 hit the South Tower. By the time the towers collapsed, all customers and employees had fled the store and the area. Dust and building materials engulfed and penetrated the building; the windows shattered, but the structure remained standing. Because Worlding leased rather than owned the building, its only property damage was to inventory and fixtures. But renovation work, neighborhood cleanup, and safety testing kept Worlding closed—and without income—for seven months.

The case of insurance coverage for Worlding’s losses is straightforward because the owners had a business package policy that provided both commercial property coverage and general liability. Worlding bought the Causes of Loss—Special Form, an open perils or all risk coverage form (as explained in Chapter 11 "Property Risk Management" and Chapter 15 "Multirisk Management Contracts: Business"). Instead of listing perils that are covered, the special form provides protection for all causes of loss not specifically excluded. Usually, most exclusions found in the special form relate to catastrophic potentials. The form did not include a terrorism exclusion. Therefore, Worlding’s inventory stock was covered in full.

Worlding did not incur any liability losses to third parties, so all losses were covered by the commercial property coverage. Worlding provided regular inventory data to its insurer, who paid for the damages without any disputes. With its property damage and the closing of the neighborhood around the World Trade Center, Worlding had a nondisputable case of business interruption loss. Coverage for business interruption of businesses that did not have any property damage, such as tourist-dependent hotel chains and resort hotels,John D. Dempsey and Lee M. Epstein, “Re-Examining Business Interruption Insurance” (part one of three), Risk Management Magazine, February 2002. depended on the exact wording in their policies. Some policies were more liberal than others, an issue described in Chapter 15 "Multirisk Management Contracts: Business".

Because Worlding was eligible for business income interruption coverage, the owners used adjusters to help them calculate the appropriate amount of lost income, plus expenses incurred while the business was not operational. An example of such a detailed list was provided in Chapter 15 "Multirisk Management Contracts: Business". The restoration of the building to Worlding’s specifications was covered under the building owners’ commercial property policy.

As these examples show, complete insurance is a complex maze of varying types of coverage. This introduction is designed to provide a glimpse into the full scope of insurance that affects the reader as an individual or as a business operator. In our business case, if Worlding had not had business insurance, its employees would have been without a job to return to. Thus, the layer of the business coverage is as important in an introductory risk and insurance course as are all aspects of your personal and employment-related insurance coverages.

In addition, emphasis is given to the structure of the insurance industry and its type of coverage and markets. Emphasis is given to the new concept of considering all risks in an organization (enterprise risk management), not just those risks whose losses are traditionally covered by insurance.

The text has been designed to show you, the student, the width and variety of the field of risk management and insurance. At this stage, the pieces needed for holistic risk management now connect. As noted above, current events and their risk management outcomes have been clarified for you, whether the losses are to households or businesses. Furthermore, you now have the basic tools to build efficient and holistic risk management portfolios for yourself, your family, and your business.

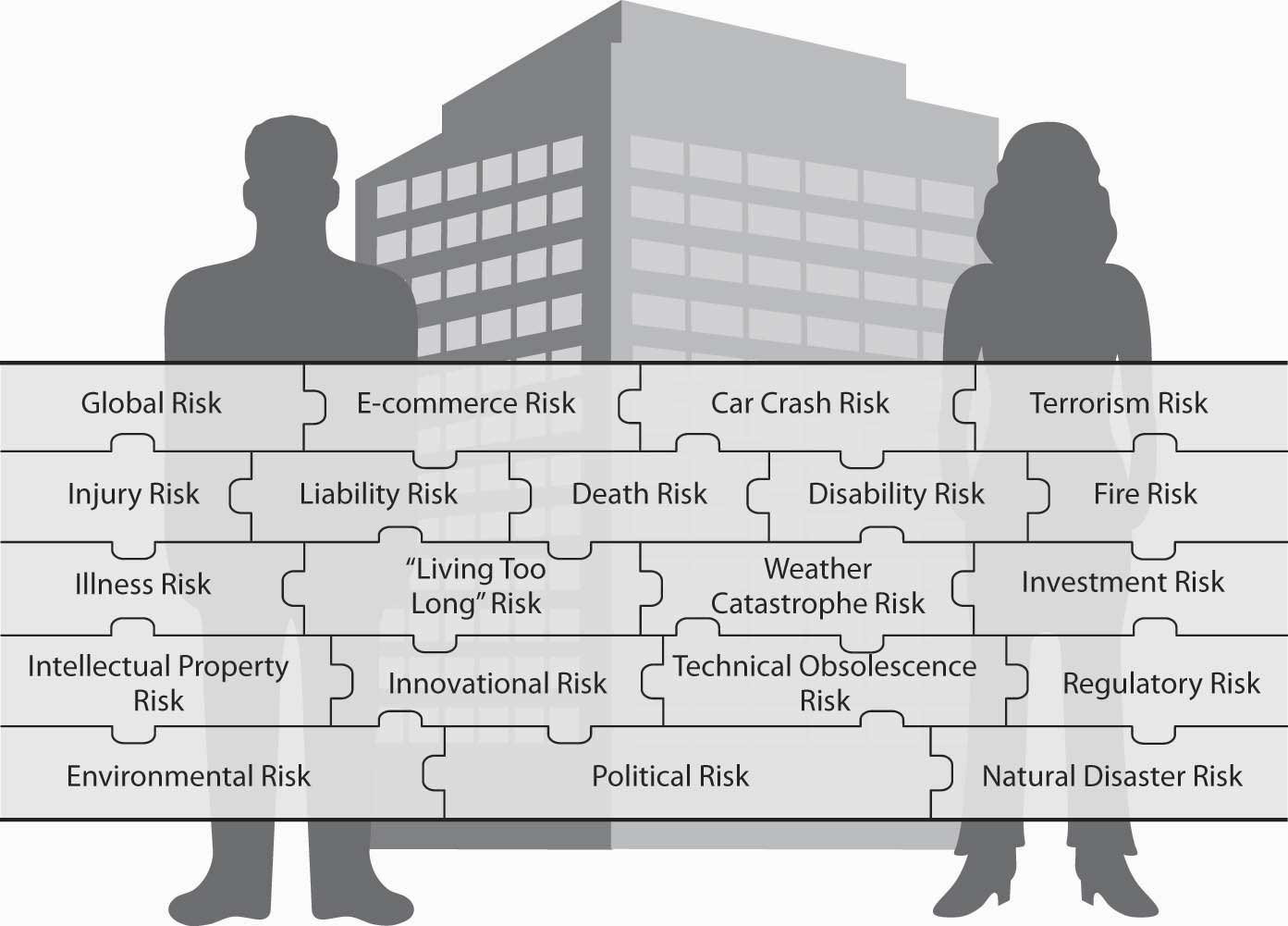

The risk puzzle piecing together the risks faced by individuals and entities is presented one final time in Figure 23.2 "Complete Picture of the Holistic Risk Puzzle", which brings us full circle.

Figure 23.2 Complete Picture of the Holistic Risk Puzzle