Getting a Job Is Only One Step to Building a Career

The first eleven chapters of this book are dedicated to getting you a job. The right job is critical to career success because it is the springboard from which you will learn important skills, develop key relationships, and demonstrate your achievements. Your career will include many jobs. Even if you stay at the same organization for the duration of your career until you retire, your job will change. You may take on more responsibility and start managing people and budgets. The company may change its focus and ask you to work on different projects.

Therefore, to build a career, it is not sufficient to know how to get any one job. You also must know how to do the following things:

This chapter gives strategies and tips for you to manage your career once you get a job. To do well on the job, you need to make a strong impression in your first ninety days. You need to transition to your new workplace. You need be clear about expected results and how these will be measured. You need to establish good communication with your boss.

You also want to develop, expand, and maintain relationships outside your immediate boss. You want mentorsA wise and trusted counselor. other than your immediate boss. You likely will have colleagues in your department and outside it. Your boss has a boss, and there might be other people in senior management or leadership positions (you ultimately work for everyone in positions above you, even if not on a day-to-day basis). You may have customer contact. You may work with vendorsProvide products or services to an organization, for example, a software vendor might provide the inventory management system for a manufacturing company. or consultantsWork with an organization but not as an employee. They might be onsite and appear to do the same work as an employee, but consultants are not on payroll and have other clients. that work with or for the organization. You also want to have professional relationships outside your organization, such as other people who work in your functional area or industry.

You shouldn’t assume that if you do a good job, people will know about it. You have to proactively manage your career with advancement in mind. Some organizations have structured performance reviewsAn evaluation of your work performance. This can be done verbally, in writing, or online., and you should know how to optimize these meetings. Some organizations do not have built-in ways for you to get feedback, so you need to learn how to ask for feedback. Some organizations have a well-defined process for granting raisesA new, higher salary. and promotionsA new, higher title that reflects more responsibility or increased influence.. Sometimes, however, you need to initiate a request for a raise or promotion.

Just because you have a job now doesn’t mean you will keep your job. The United States has employment at willWhen you are employed at will, you can be fired for any reason or no specific reason as long as there is no evidence of discrimination against a protected minority group or class. You can also quit for any reason or no specific reason., which means that organizations can hire or fire you for any reason or no specific reason as long as there is no evidence of discrimination against a protected minority group or class. It also means that you can quit for any reason or no specific reason. Therefore, you cannot look to the government or some regulatory agency to secure your job. You need to make your organization want to retain you. You need to notice the signs of an impending layoffTermination of an employee due to reasons unrelated to that employee’s specific performance. so you can protect yourself accordingly. You need to know what to do if you lose your job unexpectedly so you can get the most support possible from your employer during the transition.

An unexpected layoff is not the only potential challenge you will face. You will spend a lot of your time in your work environment, so problems and conflicts will inevitably arise. It is important to have a sense of some common workplace problems. While each case should be managed individually, we’ll cover a general roadmap for dealing with some of the more common challenges that arise.

You will be spending so much of your time at your job that you may start focusing exclusively on your job. You might neglect your personal relationships outside work, your own health and self-care, and your personal life. It is important to maintain a healthy balance between professional and personal responsibilities. You need to take care of friends and family, your health, your home, and your finances.

Sometimes, despite proactive career management, good relationships, and a healthy life outside work, you still need to leave your job. It might have been a great job when you started, but you have grown and your job hasn’t kept up. Perhaps the organization has changed. Maybe you want to do something different. You want to manage your career such that you have choices when you look for your next job. You want to have a strong network that is willing and able to help you. You want to have strong skills and qualifications that are attractive to prospective employers. You want to be learning and growing so that you are valuable to more than just your current organization.

Table 12.1 "Your First Ninety Days On The Job" gives an overview of some things you may want to address during your first few months of employment.

Table 12.1 Your First Ninety Days On The Job

| Suggested Time | Items to Do |

|---|---|

| Before you start |

|

| On your first day |

|

| During your first week |

|

| During your first month |

|

| During your first ninety days |

|

When you are new, it is a good time to ask questions and meet people. Unless you are coming into a leadership situation where people will be looking to you for guidance immediately, take advantage of your newness to collect as much information as possible. Introduce yourself to human resources (HR)The department that is charged with the welfare of employees within an organization. Subsets of HR may include employee relations, compensation, benefits, recruiting, and training. and get their advice on where you should focus to get acculturated quickly to the new organization. Remember that HR has onboardedThe process of bringing a new employee into an organization and integrating him or her to the new environment. This can be as simple as filling out paper work to get the employee paid or as involved as in-depth training and customized support to acclimate the new employee. many people before you, so they should have some good advice about how to get started smoothly. Ask your boss to introduce you to the people you should know. It is ideal that people are aware you were recently hired and are starting that day, but sometimes it’s a surprise, so be ready to introduce yourself and tell people about your background and what you will be doing.

You might be starting at the same time as several other people. Think of a school that has a well-defined academic calendar and therefore may have all the new teachers start on the same day. You might be offered specific onboarding training programs. One school sent its new hires the school newsletter for a few months before they started so they could feel they were a part of the school before they got there.

In addition to meeting key people, you must coordinate practical logistics. paper work must be filled out, including tax forms (e.g., W-2An IRS form that determines how taxes will be withheld from your paycheck.) and work authorization forms (e.g., I-9A required form that proves you have the proper work authorization to work in the United States. You do not need to prove citizenship, just that you have authorization to work.). You may have to sign a form that confirms you’ve read the company policy manual. Don’t forget to consult the organization’s policy manual regardless of whether it’s required reading. By doing so, you know any specific rules around start and end time (continuing our school example from earlier, not every school starts and ends at the same time), breaks, dress code, access to computers and other supplies, and so forth. You may need to get an identification card or keys to the office.

You also want to get accustomed to the physical environment. Confirm where to go on your first day; don’t just assume that area will be where you normally work. Sometimes large companies have several offices, and an orientation for new hires might be located in a different area. Know where the bathroom is located. Know where the cafeteria is located or get lunch spot recommendations. Know where to find office supplies. Don’t underestimate the value of being comfortable. Some companies set up a workspace for you with computer, telephone, and other equipment you will need. If this isn’t the case, arrange for these resources as soon as possible so you can start contributing on the job. Know whom to call for IT or telephone support; perhaps the organization has put together a list of frequently used phone extensions.

Remember the school that onboarded its new teachers by including them in the newsletter distribution list even before they joined? This school used particular grading software and an intranet to share lesson plans. If you are a new teacher there, you would want to make sure you have access to the system and will get training on how to use it.

From day one, you need to get down to work. Get clear about what you need to deliver from your work that day, that week, that month, that quarter. Will you shadow another teacher first? For how long will you train, if at all, before taking over the job (or in this case, the classroom)? Will you use existing lesson plans—that is, how much structure will you be given?

It is best to ask your questions before you start or when you are new. Ask your boss rather than a colleague so you know officially what to do. Get specific recommendations from your boss about how best to learn about the work—for example, who customers are, how specific forms get filled out, what software to use. Confirm to whom you should go for questions. It may be your boss, but he or she may select a colleague to train you. Find out about upcoming deadlines or special projects that insiders might be aware of but that they may forget to mention. Maybe the school where you teach collects data on the students after the first thirty days of school, and you need to be tracking specific things more closely or in a format different from what you anticipated.

Once you know what you should be doing day to day and for the next few weeks, you want to confirm with your boss how to keep him or her updated. People like to communicate in different ways. Live, telephone, or e-mail are all possible forms of communication. Find out what your boss prefers.

Find out how frequently you should update him or her. Only when you have a question? Once a day? Once a week? After a project or task is completed?

Confirm what type of update he or she would like. A quick summary? A more detailed report? Do you need to send a meeting request in Outlook for a specific time each week?

Find out how you will get feedback. The company policy manual may have information about formal performance reviews, but these are typically done once or twice each year. You will want more frequent feedback even informally so you know what you are doing well (and continue doing this) and what you need to develop (so you can work on this). Check in with your boss after your first week to let him or her know how you are feeling about your job (e.g., workload, what you’ve completed, outstanding questions), and ask for feedback then. You can also confirm how often he or she would like to discuss your performance going forward.

Don’t forget to bring paper and pen or an electronic tool for taking notes during meetings with the boss and others. A common newbie mistake is to try and retain all of the information from a meeting without taking notes. You will miss something. While it’s fine to ask clarifying questions, it looks like you weren’t paying attention if you ask about something that was already covered. You want to bring your own note-taking supplies because asking for a paper and pen, rather than bringing your own, makes you look unprepared.

Most of you have experienced the value of mentors because you already have had someone in your life—a family member or a teacher—who has guided and supported you. While your boss can guide and support you professionally, it is ideal to get mentorship beyond your boss for several reasons:

Don’t try to develop a mentor relationship with your boss’s boss. This can be awkward because your boss might think you are trying to leapfrog or exclude him or her. In addition, you lose the ability to talk more candidly. Regardless of how objectively you try to state things, if you are raising a concern or even a question about your boss, it denigrates him or her in the eyes of the person who assigns your boss the next project, promotion, or raise.

You do not need to have just one mentor. It is unrealistic to think that one person has the time or knowledge to provide all the coaching and support you need. Consider cultivating three types of mentors:

A guardian angel is what most people think of when they hear the word, “mentor.” A guardian angel is your supporter and protector. Typically, a guardian angel is two or more levels above you to have the credibility and experience to help you. Your guardian angel looks out for plum assignments that might be beneficial to your career. Your guardian angel is experienced in how to be successful at the organization and can advise you on pitfalls to avoid or opportunities to take advantage of. If you have questions about troubleshooting a sticky office situation, your guardian angel will be able to help. For our new teacher in the earlier example, his guardian angel might be a senior teacher or even administrator. This person might propose learning tools or conferences the new teacher could use or attend. This guardian angel also might suggest the new teacher for a committee or other special assignment to raise his profile at the school.

A shepherd is typically not much more senior and may even be more junior to you. A shepherd knows the ins and outs of the organization and can guide you. We all know someone who is the social epicenter of a particular group. For your professional workplace, that is a shepherd who can help shortcut your learning curve. The shepherd knows who is influential, who might be trouble, and who is the best person to talk to for a variety of requests. The shepherd would be a good person with whom to brainstorm about possible other mentors. For our new teacher in the earlier example, his shepherd might be another teacher at the school, who doesn’t need to be of a similar subject or grade, but someone more connected to the culture of the school and who can share the inside scoop.

A board of directors for a company (or board of trusteesAn analogous group to the board of directors, but for a nonprofit. The trustees do not work for the nonprofit, but are a separate entity to provide outside advice and support, including financial and fund-raising support. for a nonprofit) is typically composed of people with different backgrounds and expertise—finance, legal, human resources (HR), operations, marketing, and so forth. The board provides a resource for advice and counsel to the company or nonprofit in a variety of areas. Similarly, you will need advice and counsel on a variety of areas—career advancement, communication and presentation, work and life balance, career change, and so forth. No one person will be an expert in all issues. Instead of relying on one person, it would be helpful to cultivate a board of directors, each with a specific area of expertise important to you. It is ideal to have mentors both inside and outside your organization and even industry. This way, you have a diversity of perspectives. The new teacher might get mentorship from another teacher of a similar subject or grade to provide pedagogical advice. If he has an interest in using more multimedia or innovative teaching approaches, he might ask for guidance from a teacher outside his subject area who knows a lot about audiovisual technology. Even a school operations staff member might be a member of this teacher’s “board” to inform him how the school functions.

Mentorships are close relationships, so it is ideal when they develop naturally. Sometimes, organizations have formal mentor programs, and these are great resources for meeting people and sometimes for establishing mentorships. But don’t rely on a formal mentor program because your employer might not have one or the match you get may not be ideal. Instead, be proactive and use the following tips to help you seek your own mentors:

When you are just starting in an organization, find a shepherd to give you a lay of the land. You need to get acclimated to your new environment. Then think about your goals for next year, two years out, and so forth, and think about what you need to know or what skills you need to develop. This gives you an indication of where you may benefit from mentorship.

Identify people in whom you are genuinely interested who might be able to provide advice and counsel toward your goals. Meet with them for breakfast, lunch, or dinner. If you can work on a project with them, that is another way to start a relationship. You should not automatically assume someone will agree to mentor you or would even be a good mentor. Right now, you just want to see who you enjoy being with and who can also provide the mentorship you seek.

For those people who might be possible mentors to you, you do not need to ask them as formally as you would a marriage proposal—that is, no bended knee before saying, “Will you mentor me?” Instead, let them know that their advice and insights in past conversations have been helpful and ask if you can reach out to them on a more regular basis to continue the conversations. Sometimes people will say they don’t have the time to commit to something regularly, but sometimes people will be flattered and enthusiastic. You will need to meet with many people before finding the right mentors, so don’t be concerned if your first efforts are not fruitful. At the very least, you are meeting people and practicing networking and relationship building.

When you do secure a mentor, you want to be a good mentee. Mentorship is a relationship, so you are equally responsible for its success. You are initiating the relationship, so be mindful of how the mentor likes to communicate and at what frequency. Is it better for him or her to meet at breakfast or after work, rather than during the day? Does your mentor want to have a sit-down meeting with an agenda or a quick conversation when you both have the time? Be proactive about scheduling the meetings so that the mentor isn’t doing the work to maintain the relationship.

Get to know your mentor as a whole person. Find ways to be helpful to him or her. Many mentors enter these relationships because they want to give back. At the very least, let your mentor know about the impact he or she is making by providing results updates—what happened when you took the advice they gave? If you know your mentor has a specific hobby or interest, find a helpful article or recommendation to support that interest.

Remember that your needs and your mentor’s availability change over time. Mentorships evolve, so if you find that you have less to discuss and the relationship has run its course, schedule less frequent meetings. Turn the mentorship into a friendship, and steer the discussions more personally or outside the question-advice format. Treat your mentorships like two-way relationships with give and take.

A strong professional network is not just about mentorships. You also have colleagues who provide emotional support and more direct support, perhaps, on joint projects. You may be in a role that has customers. You may be working with consultants or vendors. Your job may require you to partner with other organizations. For your own knowledge and expertise, it is helpful to know about organizations and people outside your own employer. Organizations evolve over time, so it is helpful to know people at all levels—your peer could become your manager, or you may be asked to lead a team composed of peers.

Knowing people in different departments, at all levels, both inside and outside your employer, ensures that you have a diversity in perspectives about your role, your organization, and your industry. You may have a very specific role right now, but as your responsibilities expand, you will likely have to work with more and more people. It is helpful to establish relationships before you are forced to work together.

Our new teacher would want to know people in his school but also in other schools. If he teaches in a public school, it would be helpful to know people in independent, charter, and other schools. People in the school’s administrative department or other school governing body would also be helpful contacts. Academics and experts in education, donors and supporters of education organizations, and parent organizers are other potential contacts for a teacher.

You need to be thoughtful and proactive about relationship-building to have quality relationships with mentors, colleagues in different departments, colleagues at different levels, and people outside your employer:

People are busy, and you are busy. If you wait for an opportune time to start building your network, you will not find one. There is no urgency to day-to-day networking, so it will be set aside for a later time that never comes. Instead, schedule a few hours each week with the goal of expanding your professional network. You might set aside one lunch hour per week to eat with a different colleague. You might join a professional association and attend their meetings and mixers. One new teacher volunteered to be her school’s union representative. She wanted to learn about the union, and though she was new, she was the only one who volunteered, so it was great exposure in her very first year. You might play on your employer’s softball league. You might volunteer to organize the office holiday party. Many opportunities exist to meet a diverse mix of professionals both inside and outside your employer, but you have to consciously set aside the time to do this.

Are you comfortable introducing yourself to people and telling them what you do? Networking is one of the six job search steps, so you probably have worked on your networking pitch to get a job, but in the daily work context, your pitch is about what you do now. Plan and practice what you will say.

If the thought of joining a professional association and going to meetings makes you uncomfortable, consider joining with a more extroverted buddy. The softball league or a volunteer committee might provide a structured outlet for your networking. Find a colleague who isn’t shy and ask them to introduce you to people. People are often very happy to help and may not realize you are shy. Let your boss know that you are trying to meet people, and ask him or her to introduce you to people.

Once you meet people, make time to maintain and expand relationships over time. It is impossible to schedule regular live contact with everyone in your professional network—colleagues, customers, vendors, management, former colleagues (as you progress in your career), and people in your related function or industry. However, you can keep in touch with phone calls and e-mails. The same spirit of generosity applies as you expand and deepen relationships—maintain contact without asking for anything in return.

Even from the earlier sections of this chapter, you can see that your day-to-day job is just one part of your work experience. paper work, company policies, and physical environment also are a part of your job. You also have professional relationships. Even if you look only at yourself and what you do, you still are responsible for more than just your day-to-day job. You also are responsible for your overall career; these are two distinct entities.

Your day-to-day job is what you were hired to do now. It is meeting the success metrics that you confirmed in your first ninety days. It is having a good relationship with your current boss.

Your overall career is made up of your day-to-day job and your future jobs; therefore, career management means staying marketable and ready for future jobs that will be different from the job you are doing now.

To continue the schoolteacher example, his day-to-day job is teaching his students in the class he has now. Maximizing his overall career also includes staying current on pedagogy and his subject expertise. It also includes getting additional certifications. If he aspires to school leadership, teaching excellence will be just one part; he needs administrative experience in school operations; he needs to coach other teachers; he needs to stay abreast of the latest teaching innovations and challenges because as a leader he needs to guide his school through changes in education. This schoolteacher, therefore, needs to meet his day-to-day job demands, while fitting in the development of additional skills and experience required for his desired future job.

An accountant might be assigned a specific area of tax and a specific type of client. Her day-to-day job is about completing the tasks at hand. Later roles will involve overseeing an entire project and multiple accountants, who, like she once did, just manage certain tasks. Later roles might require overseeing entire client relationships with multiple projects. Finally, this accountant will be expected to bring in new clients; her primary focus becomes selling projects rather than managing projects or performing accounting tasks. This accountant, therefore, needs to perform her accounting tasks, while maintaining perspective on the overall project, developing management skills, and ultimately developing client relationship and selling skills.

The ability to manage both your day-to-day job and your overall career requires good time management and self-awareness of your dual tracks. It is a time management issue because you need to do the daily work of your job and still prioritize time for career-building. You also must have self-awareness of what you want to achieve, your ideal timetable, and what you need to meet these goals. When you are new in your career, your main priority should be to be the best performer you can be in your current job. As soon as you have acclimated to your environment and mastered your daily work, it is time to start proactively scheduling in the training, research, and relationship-building activities you need to prepare for your next role. Do not just assume that opportunities for career advancement will come to you.

One way of knowing that you have mastered your daily work is by getting feedback on how you are doing at your job. Some organizations have formal feedback processes, where your direct boss and sometimes even colleagues or other people who work with you fill out a performance feedback form. These forms typically include criteria for the technical skills of your job and soft skills, such as communication skills and relationship skills with others. When you join an organization, find out if it has a formal performance review process. Find out its frequency—it could be annually or several times per year. Some organizations (e.g., management consulting firms) give formal feedback after every project. Ask to see the performance review form when you start because it is a great indication of the criteria by which you will be judged.

Unfortunately, not every organization has formal processes in place, or, if they do, not all managers actually give the review in a timely and thorough way. Your employer might have a formal process, but if no one follows it, you still don’t have your review. In the case where you aren’t getting formal performance feedback, you need to ask for it. In the first section on how to do well on the job, we covered the importance of regular updates with your boss. This alone should ensure that a formal performance review has few surprises. However, these shorter updates are not a substitute for a more thorough review of your performance. Schedule a meeting with your boss well in advance, and let him or her know you would like to discuss your performance.

At a formal performance review, you want to cover four topics:

Don’t assume that your boss is aware of everything you are working on and have accomplished. Some jobs have narrowly defined tasks, but many jobs have ad hoc projects that arise. Sometimes you take over the duties of a colleague if your area is restructured or the colleague is assigned to other things. Your boss may lose track because he or she might have other direct reportsThe person you manage directly, including delegating assignments to that person, giving feedback and being responsible for the direct report’s development, and determining raises and promotions. and his or her own responsibilities and daily work. The new accountant, for example, might have been expected only to be a junior member of a project team, but maybe the manager got called onto another project for a few weeks, and the new accountant stepped up. She needs to make sure her boss realizes that she went above and beyond on a project.

Come prepared to your performance review with a list of your current responsibilities and past accomplishments. Listen closely to what your boss sees as your responsibilities and past accomplishments. Make sure you are on the same page—maybe you are prioritizing a part of your job that your boss sees as trivial. Maybe your boss highlights a win that you overlooked or dismissed as unimportant. The new accountant might be spending a lot of time formatting specific client reports rather than talking to the client and getting verbal input on what they’re thinking. Maybe the firm would prefer that she get in front of the clients more, rather than focus on the written correspondence (or vice versa). Come to agreement on any gaps between how you evaluate your performance and how your boss evaluates you so that you know the criteria on which you are judged for the future.

In the spirit of agreement, confirm priorities and expectations for the upcoming months or year (depending on the frequency of when you get a performance review and how quickly your duties typically change). Make sure you are working on the tasks and projects that matter to your boss and to your department. Be prepared to discuss what you plan to work on, but be open to the possibility that your boss might reprioritize your work. Having a prepared list of upcoming tasks and projects also makes your boss aware of everything you are doing—remember, he or she has other direct reports and responsibilities and may not realize all you’ve been assigned.

Ask for feedback on your strengths and what you did well. Don’t assume that a performance review is just about improving and therefore discussing your weaknesses. Knowing your strengths is equally important so you know what to build on and do more often. Continuing the example of the schoolteacher, many schools observe teachers in the classroom and give instructional feedback (this is done by the principal and possibly dedicated instructional coaches). A new teacher might not realize how effectively he is engaging his students by mixing up the lesson into lecture, small group, and independent work. Once that is pointed out in a performance review, the teacher knows to build this into future lessons.

However, you also want to address any weaknesses or areas to develop. Don’t get defensive; just listen and schedule another meeting after this review if you still disagree with the feedback once you’ve had time to absorb it. Ask for specific examples so you are clear on what behavior isn’t desirable or how your skill in a weak area is deficient. Get your boss’s recommendation for how you can address these weaker areas. Do you need to get on a project to hone these skills? Is there any training you can attend at the organization or offsite? Can your boss give you more regular coaching on a day-to-day basis? Continuing the example of the new accountant, she might have struggled on a project that required a specific industry expertise or area of accounting. Her boss might recommend a training course to develop this expertise, or she may be placed on another project in the same industry or accounting specialty so she can get more exposure to that area.

If a number of weaknesses are revealed, or if there is a wide disagreement between what you and your boss think (in terms of what you accomplished, your future priorities, strengths, and weaknesses), you want to get agreement on the next steps to fill this understanding gap. You probably want to schedule another meeting in the not-too-distant future to check in or at least step up your regular updates. It is important that you know how your job performance is being perceived and that you build on your strengths and improve your weaknesses.

Your main priority when you are new on the job is to master the job. You will learn from your performance reviews how you are doing and if you are ready to take on more responsibility. Some organizations have very specific career tracks with well-defined schedules for when the typical employee progresses to more responsibility and a formal promotion in title. As with performance reviews, however, not all organizations have a formal or well-defined process. Over your career, you may be in situations where you need to ask for a promotion.

You need to have a good understanding of your organization’s culture to know the best timing and case for a promotion. In a flat organizationAn organization with few or no titles to differentiate employees. An organization might opt for a flat structure to strongly encourage teamwork., where there are few titles, the chances of a promotion are fewer due to the flatter structure. Even where a range of titles exist, if you see that people with the more senior titles have many years’ experience, then you can approximate that the track to each promotion requires many years. There are always exceptions, so you want to look at individual cases in your specific organization, but the flatness of the organization and the title track of people already within it are two good indications of how promotions are viewed.

It is ideal to already be doing a bigger job before requesting a promotion. You want to have earned your promotion. It will not be given on promise or potential. In this way, you want to structure a promotion discussion much like the performance review meeting. You want to itemize your current workload and past accomplishments, which should demonstrate that you have taken on more than your current title suggests. You want to confirm your future projects, which should indicate a bigger role with more responsibility. You want to highlight your strengths.

Know the exact title you want and what you plan to do in the role. If your boss agrees, get confirmation of when the promotion will take place and ask for something in writing documenting your new position and responsibilities. This way, you ensure that everyone has the same understanding and that your promotion has officially gone through the proper channels of approval.

If your boss doesn’t agree, get a clear understanding of why so you can plan your next steps and manage your career accordingly. If the timing is too soon, find out when you can revisit getting a promotion. If promotion approvals occur only during certain times of the year, mark your calendar so you catch the next decision process. If your boss disagrees about your achievements or skills, ask for recommendations on how to improve. You are not entitled to a promotion, but you also don’t need to sit idly by and just wait for one. Document your achievements, make your case, and act on feedback that you receive.

A promotion and a raise are different, although they sometimes go hand in hand. As with promotions, some organizations give raises on a regular schedule, typically annually either at your start date anniversary or at the same time every year for the whole organization (in which case, the raise is prorated for your start date in your first year). Sometimes raises are pegged to inflation; this raise is known as COLAA specific raise that is indexed to inflation or a cost-of-living adjustment, hence the acronym COLA., or cost of living adjustment. Sometimes raises are performance based, in which case strong feedback or specific results (e.g., sales) determine the raise.

As with promotions, you want to know what is customary for your specific organization. This doesn’t mean that you can’t ask for an exception, but you will at least know what to expect and to brace yourself to make a case if what you are asking for is exceptional. You might consider asking for a raise if your job has changed dramatically and you are taking on more tasks and responsibilities. Another reason to ask for a raise outside the yearly increase is if you have new market information that shows salaries in similar positions are dramatically different from your own.

A raise implies a permanent adjustment to your salary. Your employer may not want to do this if your additional responsibilities are temporary. In this case, you might ask for a spot bonusA bonus that is not paid on a regular schedule (e.g., annually) but rather paid out for an extraordinary accomplishment or extra work above and beyond the day-to-day job., or one-time bonus, to compensate you for your extra work. Remember that going above and beyond your daily work is how you distinguish yourself, so in and of itself that is not enough to justify a raise or bonus. A raise or bonus is warranted in extraordinary cases, and the measure of what is extraordinary varies by organization.

As with promotion requests and performance review meetings, you want to come prepared with your accomplishments as evidence you deserve a raise. The raise meeting is the time to share any market data that you learned. Be informative, but not threatening. You don’t want your employer to think you are giving an ultimatum that you get the raise or else you will quit. They may call your bluff. Instead, reiterate how excited you are about your position and affirm that this is the right organization for you, but make your case why a raise may be merited for what you have done.

The recent high unemployment numbers underscore that an important part of career success is staying employed even when the economy is difficult. The first three sections we covered in this chapter all contribute to securing your job:

However, sometimes even good workers get laid off. Companies buy or merge with other companies, and this often means there will be overlap—for example, two human resources (HR) departments, two accounting departments, and so forth. The new company may not need or have a place for everybody. Organizations may close their doors altogether. Enron, Bear Stearns, Lehman Brothers, and several nonprofits with money invested with Bernie Madoff closed quickly, without any warning in some cases. Therefore, knowing that layoffs can happen through no fault of your own, you want to be able to see the warning signs (so you have more time to react) and manage a layoff so you get the most support and momentum to move on to a new job

It’s hard to predict the exact timing of a layoff, but certain events indicate that you should start paying closer attention to the health of your organization and the security of your job:

If the overall economy is stagnant or depressed, repercussions are felt throughout many industries. Public schools are impacted by state budget cuts. Hospitals face shrinking federal funds. Nonprofit endowmentsPool of money set aside by a nonprofit to be invested and drawn upon for its operating expenses. decrease and, subsequently, so do their operating budgets. Consumers spend less, so retail stores have lower sales and lower revenues. Businesses have less money to spend on advertising, technology, consulting, and other business services. If the economy takes a hit, your employer likely takes a hit. If the economy suffers a deep blow, it might be enough to threaten your employer’s ability to maintain its workforce.

Sometimes specific industries are hit especially hard. Housing has undergone a recent contraction, so mortgage services, builders, housing-related equipment and supplies, and other real estate-related companies are struggling. If you hear that your employer’s competitors aren’t doing well or that your broader industry isn’t doing well, follow the news more closely. If an industry your employer serves isn’t doing well, that impacts you just as directly. For example, when car companies were having financial trouble, the advertising agencies that relied heavily on automotive company business also were hard hit. The Occupational Outlook Handbook produced by the Bureau of Labor Statistics tracks hundreds of different jobs and gives estimates on future job prospects for that role.

You may be tempted to disregard your organization’s internal memos, newsletters, or even annual report, but it is a good idea to stay current with your organization’s health. Is it profitable? Does it have a diversifiedHigh amount of diversity. A diversified customer base could mean you have several customers, so business is not concentrated in any one customer. It could also mean the customers are in different industries or sectors, so business is not subject to the financial health of any one industry or sector. customer base—that is, a lot of different customers, so you are not relying on any one group? Is your employer growing? Is the growth related to your job, or is it in a different geography or different functional area?

If your organization’s management changes, that is a sign to follow your work environment and prospects more closely. It is customary for a new executive team to want to bring in their own people. If you are new to your career and many levels below the executive team, this may not affect you now, but it’s something to remember as you advance upward in your career. In addition, if your immediate boss changes, the new boss may want to bring in his or her own team, and that does affect you, regardless of how junior you are.

Earlier in this chapter, we talked about keeping open communication, developing relationships, and getting feedback. You want to do this on a regular basis because changes in the behavior of your boss or colleagues (or team when you start managing others), as well as changes in your responsibilities or your performance feedback should be watched closely. You want to have time to turn things around if you discover people are not happy with your work. If you can’t ameliorate the situation where you are, you want to have time to look for your next opportunity and leave on your own terms.

A layoff doesn’t have to mean you did a bad job. If you are let go for performance-based reasons, by all means learn from that. If you are fired because you didn’t get along with your boss or coworkers, try to establish better relationships at your next job because professional relationships are important. If you were laid off due to a bad economy, restructuring, or other external reason, let the job go and focus on moving on to your next job.

To make the most out of a layoff situation, you can take action steps at different stages:

Layoff scenarios will vary based on how much lead time the organization has to prepare and how many resources it has to support the layoff. A small business with few employees will handle layoffs differently than a large, global company with thousands of affected employees. The following is a roadmap for managing the termination process in a large organization that has resources to provide support for laid-off employees.

Once a layoff is announced, you will meet with HR to discuss the terms of your severanceMoney you are paid after a layoff. This might be in a lump sum, or the organization might keep you on payroll and continue your salary even when you are not working there. and your end date. Prepare for this meeting by reviewing your organization’s manual and any information about the severance policy. Some questions to consider include the following:

Ideally, you have a friend in HR who can explain the policies to you before the termination meeting so you know what to expect and what you want to negotiate if you need more than the policy dictates. Severance packages are negotiable.

During the termination meeting, listen closely and take notes. Fully understand the severance package being offered. Ask questions if anything is unclear. Agree to get terms of the severance package in writing. Schedule a follow-up meeting for after you have a chance to review these items. Do not negotiate yet because you want to take time to prepare.

Remember that the organization probably regrets having to lay you off and wants to help you. Once you have received your offer, check what is customary for organizations similar in size and in your industry. You might want to negotiate for some of the following items:

Collect contact information for the people with whom you’d like to keep in touch. Don’t forget to share your personal contact information because most of your colleagues are used to reaching you at your work e-mail. Arrange with the IT department to have an automatic reply to your work e-mail that enables people who are trying to reach you specifically to have access to your personal information. If you do not want to share your personal information with everyone who may contact you at work, create a temporary account on Gmail or Yahoo! specifically for this forwarding purpose. Have the temporary Gmail or Yahoo! account forward to your primary personal e-mail and then you can decide if you want to share your information at that time.

Thank your boss, management, colleagues, and direct reports. Even if you are not personal friends with all these people, you may need them for references or job leads. For people whom you know you want for references, ask them while you are still on staff so you can do so personally. Get their personal contact information, in case they get laid off, too, or otherwise leave the company. Collaborate with your boss on what details of your layoff will be distributed both inside and outside the organization. You want to make sure you have a consistent and positive story.

Check with HR to see if there are consulting opportunities within the organization or openings at subsidiariesA subset of the organization. An organization might split into subsidiaries so that each subset can focus on a different product or service, or otherwise remain separate from other subsidiaries but still be connected to the whole organization. or partners of the organization. Find out if a formal process is necessary to submit your résumé or arrange interviews.

Some organizations require that you leave your office the same day you are laid off. You may not have time to take all the preceding steps. If you know this is a possibility where you work (check what is customary for your industry and also how your organization handled layoffs in the past), make sure you have personal contact information well before any danger signs are visible. Make sure you can quickly pack your office and take what you need. Do not keep your personal contacts only on your office computer or office phone because you might not have enough time to pull these contacts off before you lose company access to this information.

It’s fine to take time off to recharge, but don’t mistake your severance period for a paid vacation. Use that time to start your job search while you still have a cash cushion. Don’t wait until you are running out of money and then cram in an anxious and desperate job search.

Run your numbers on how much cash cushion you have (given severance, savings, and so forth) to give you a timetable for your job search. A proactive job search typically takes three to six months. If you need money coming in sooner, you might want to build in time for temporary or consulting work in addition to your job search.

Your job search is now your full-time job. Schedule time for specific job search activities. Prioritize your job search so you are not tempted to spend this new “free time” reorganizing your house or doing non-career-related projects.

When you work side by side with people, many different people and personalities are interacting, so conflicts inevitably arise:

These examples present challenges in day-to-day relationships. Relationship management is a key skill to mitigate common workplace conflicts. Your mentors, especially your shepherd, can help you by forewarning you of colleagues who might be problematic and advising you how others have learned to work with those people. You might simply need to set boundaries and establish a working relationship for the future.

If a colleague interrupts your work, don’t continue the conversation. If you engage her in conversation, she might think you welcome her interruptions. Let her know you have a deadline and ask if you can come by at a set time. Make sure you schedule a time that is specific and limited. She will likely get the message—though it may take a few times—and stop interrupting you. You have set a boundary and a standard for how you wish to be treated.

If a colleague isn’t pulling his own weight, your strategy will depend on his seniority to you (if you are peers, it’s less complicated than if he’s senior), your working history, and whether you expect to be working together in the future. React more carefully if your lazy colleague is senior, in case he has more influence with your boss. If your working history has been good in the past, you might decide to give your colleague the benefit of the doubt or reach out and candidly offer your help. If you expect to be working together on an ongoing basis, it is more important that you first establish a good working relationship. Get help from your mentor on how to deal with the situation in a way that reflects the culture of the organization as well as the relationship and power dynamics.

If a competitive colleague takes credit for your idea, make sure you document your ideas and speak up so that she is unable to do this. She might not realize it’s your idea and is merely repeating what she heard. She might do this intentionally, but once you stand up for yourself, she’ll move on to others. This underscores how important it is to have regular updates with your boss where you can let him or her know firsthand what you are contributing.

If a colleague is unresponsive, recognize that there will be many situations where you have to influence people to help you, even when it is someone over whom you have no direct authority. This is a great skill to learn. The causes as to why someone may be unresponsive differ widely, but you can help the situation by making clear requests with specific deadlines. People are busy, and if you don’t get what you need, rather than assume someone is deliberately being unhelpful, be clear and help people help you.

These are just some examples of workplace conflicts, but others will occur because your work environment combines many different personalities, roles, and cultures. Good communication and relationship-management skills will help you tremendously. If you have mentors who can provide a sounding board, as well as the cultural and historical context for people’s behaviors, that will help tailor your good foundational skills to your current environment.

It is always a good idea to work with your mentors to help manage workplace conflict. Depending on the seriousness of the issue, you may also want to call on HR, which includes people specifically trained in employee relations, employment law, and other areas helpful to mediate workplace conflict.

In the “Learn How Your Employer Runs Its Business” section of this chapter, we recommended you read the company policy manual within your first ninety days. Often, you are required to sign confirmation you have read and are familiar with the policies. It’s important to keep the manual handy so that you know how to manage some of the following uncertainties or conflicts beyond daily relationship struggles:

Technology policies evolve quickly because of the increasing importance of social media. By the time this book is published, standards likely will have changed. Currently, some employers monitor all employee e-mails sent on office equipment, whether from a personal e-mail account or not. Some employers block access to sites like Facebook or LinkedIn. Be careful if you have a personal blog. Your employer may still consider that what you say reflects on them. You want to check what is allowed and customary at your own workplace.

Generation Y (born 1980–1995, so they are today’s entry-level workers) is an entrepreneurial generation. It is not unheard of to find people with a side business, perhaps a website or a consulting business. This could be a violation of company policy, so even if you do the extra work on your own time and don’t think it interferes with your work, you want to make sure it is not a violation. A conflict of interest might occur, and working another job could be grounds for dismissal.

Similar to a job on the side, office dating may be explicitly covered in company policy. Even if it isn’t, weigh the decision carefully to date a colleague. If the relationship doesn’t work out, you still have to see this person. In addition, even if you and the colleague you are dating are both fine with the decision to date, other colleagues may react differently. When you are early in your career, you have a short track record, so your reputation is built with what you do every day. Weigh possible adverse perceptions carefully.

Don’t assume you can just e-mail or take your work files out of your office. If you are dealing with customer data or information that must be kept confidential, taking information offsite may be against company policy. Your home office equipment may not meet security requirements. You might have to log into a specific server to access your work files so that security is maintained. Again, don’t just assume. Check your employer policy.

If you think a colleague is harassing or discriminating against you, this is a good example of when you might want to speak with HR. When you bring issues to HR, they need to start an official investigation, so make sure before you do this that there really is a problem and not a misunderstanding that you can handle on your own. Maybe the boorish colleague does not mean to discriminate, but just has terrible judgment or poor taste. Your mentors can help you assess the situation based on exactly what happened, what they know of the colleague in question, and any other nuances specific to your employment situation. You should never tolerate harassment or discrimination, but use good judgment on the best course to pursue.

Workplace conflict can be tricky and varies widely, so it’s impossible to cover every scenario or make very specific recommendations. Some good rules of thumb include the following:

Some employers check credit history before extending offers. One of the reasons for this is the notion that a person’s ability to handle money responsibly is a signal of overall responsibility. This is a well-defined example of how your life outside of work (in this case, your finances) impacts your career success. When you transition to your first job, you have a number of financial issues to manage:

Even if this isn’t your first job, financial transitions will occur throughout your life—for example, buying a home, getting married and commingling finances and legal obligations, and having children.

For both the entry-level and the experienced worker, your financial situation dictates how much risk you can take, which may limit your opportunities. If you are living paycheck to paycheck, you might need to tolerate a less-than-ideal work situation. You might not be able to take a chance on a new business or a job change.

Personal finances matter. You can start some good habits start early in your career:

In addition to good finances, good health is part of the foundation for career success. You physically can’t do the work if you don’t take care of your health. Once you know your typical work schedule in your new job, schedule time for exercise. Some workplaces have gyms, or you might look at nearby gyms as an option to make time for exercise.

Schedule your annual physical, dental appointments, and other routine medical care. Put these appointments into your professional calendar so you don’t schedule meetings on top of these and push them off to the side. Try scheduling as many routine checkups as possible before you start your job so that you can focus 100 percent on the new job.

Make time for breaks, eat lunch, drink water, and practice good health habits even during the workday. When you are new, you have a lot of information to process and you may be tempted to work through breaks or lunch, or never leave your desk. Set your Outlook calendar to remind you to stretch. Block off your lunch hours and make dates with colleagues so you keep the time free. You need to replenish your mental and physical energy so you are able to focus and do good work.

You might be tempted to work past the regular day, or do career-related activities after work (e.g., professional networking, training). While this is admirable, you also want to pursue hobbies and personal interests outside work. First of all, personal hobbies make you a more well-rounded person, which helps your career. Second, focusing on personal hobbies gives you a more diverse network, which also helps your career. Finally, pursuing personal interests gives you a much-needed mental break, which should help you be more focused and possibly more creative in your job.

Not every relationship needs to contribute to your career success. Consider involvement in your community. Don’t forget your social circle from college and other non-work-related situations. Similar to personal hobbies, personal relationships outside work make you more well rounded and give you a diverse perspective. It is easy to overlook these relationships, so schedule time on your calendar on an ongoing basis so that these relationships are not continually pushed aside for work reasons.

In the beginning of this chapter, we introduced the notion that your career is a succession of jobs. So you should start your career fully expecting to hold multiple jobs. Even if you stay at the same organization, your job within the organization will change:

Your own organization is a possible source of future jobs, so you should know your organization much more broadly than your current job. Know the different departments. Know the different clients and constituents your organization serves. If your organization is part of a larger group or has partners or subsidiaries, get to know these as well. You want to know the structure, what types of jobs are available, and the protocol for moving from one part of the organization to another. Some organizations have very clear rules about applying for internal jobs—for example, you need to get your current boss’s permission before applying; you need to apply through HR or use another special application.

Staying in your current organization is not your only option. Keep in mind, however, that in the beginning of your career, it is valuable to establish a track record. Staying at a job for one year or longer has value in the duration itself because you show that you have staying power and can follow through. People change jobs more frequently now, so prospective employers are not as critical when they see various employers on a résumé. However, multiple short stints of two years or fewer raise a red flag for employers that you might leave them just as quickly, or are otherwise unable to last. Recruiting and onboarding is expensive and time consuming, so prospective employers shy away from candidates who might be a flight risk.

That said, several signs might show that you have outgrown your current organization:

Each of these options represents a different type of opportunity and therefore a different search.

If you are leaving for a challenge, then your search needs to focus on jobs with broader responsibility or expertise requirements than you have now. Be clear on how you will measure the amount of challenge: Are you looking to manage a team? Are you looking to have responsibility for a budget or finances? Are you looking to learn a specific skill? Your ability to define specifically what you want in your next job will enable you to search for those opportunities in a targeted way.

If you want to focus on a different specialty, skill, or geography, then you want a career change. You are not just taking the outline of your job and moving it into the context of another organization. Rather, you are changing a fundamental piece of it—industry, function, or geography.

If you are leaving to go into business for yourself, this is also a career change from traditional employment to entrepreneurship. You will have the day-to-day job as well as sales, marketing, operations, finance, and all functions of running a business. The schoolteacher who decides to open a tutoring service will still be teaching but also will need to market his services, sell to prospective parents, bill his hours, collect money, balance his books, and so forth. The accountant who opens a private practice similarly has to market, sell, and run operations of an accounting firm, in addition to accounting.

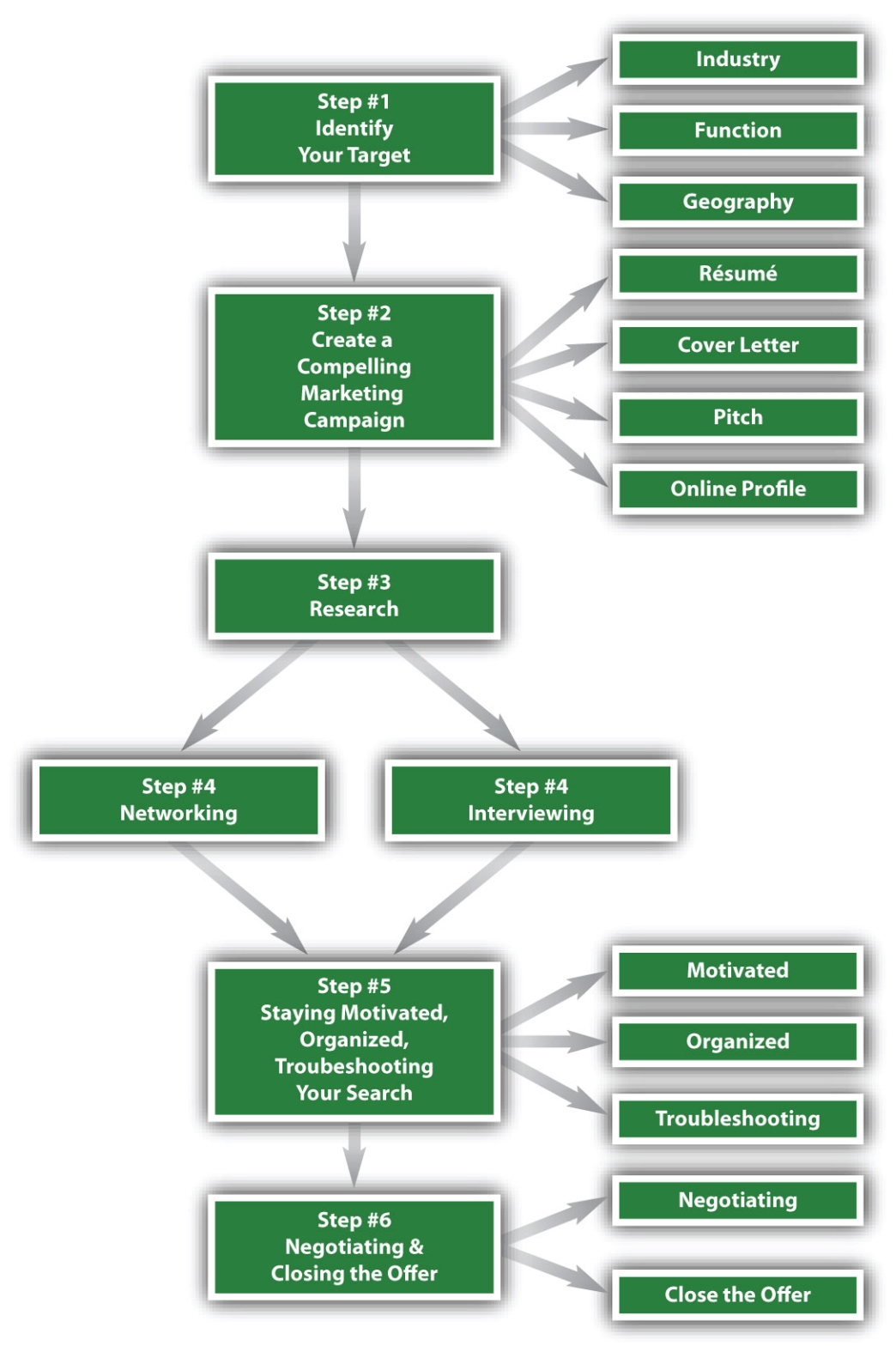

The job search always starts with targeting so that you can customize each subsequent step to your target. Once you have determined how your next job is defined, you can move through each of the same six steps you used to get this first job.

Remember to update your marketing materials to reflect everything you have accomplished in this new job. It is good practice to update your résumé on an ongoing basis even when you are not considering a new job. Whenever you complete a new project, take on additional responsibility, or learn a new skill, add it to your résumé. This way, you are not scrambling to remember everything you accomplished (you can always edit it). Another benefit to frequent updating is it is a built-in check and balance that you are accomplishing, progressing, and learning in your job. If six months have passed and you have nothing to update, look into opportunities for training or taking on additional projects to stretch your skills and experience.

Networking is another job search step that will have changed from your first search to this current job. Your network has grown since your first job search. It now includes people you have met in your current job, as well as any professional groups you might have joined. It also includes people you met as a result of your first search. Don’t overlook helpful people from your first search.

The six-step job search is effective because it is thorough and enables you to retain control of your search. Because it is thorough, it takes time. You must be able to spend time on your job search without compromising your ability to do your current job. From an ethical standpoint, you have committed to this job, so you need to produce. From a practical standpoint, you need to have good references from your current job for your next job, so you must maintain good standing with your current organization.

You will be able to do a lot of your job search outside normal business hours. You can update your marketing materials, research new possibilities, and reconnect with your existing network on evenings and weekends. Once you start networking outside your immediate circle and interviewing for specific jobs, you will start to intrude on your normal workday. Save your lunch hours, vacation days, and personal daysPaid time off that is separate from your vacation days. Some organizations break out personal days from vacation days because they might have different requirements for claiming these (e.g., less advance notice, ability to use a few hours at a time, rather than just whole days). in anticipation of using them for your job search.

Another area for preplanning is your appearance! If your organization does not require formal business attire, then you will stand out in your interview suit. You might consider dressing more formally on regular days so that your interview clothes do not diverge so far from your daily wear. You also might consider not wearing a blazer at your current job, but then adding it once you are offsite.

Plan ahead for if and when you will let mentors and your boss know about your job search. You will want references from your current job, ideally from your direct supervisor. In some cases, you want to keep your job search confidential, so you can refer prospective employers to a customer who knows your work, a senior colleague who has worked with or directly supervised you, or a former colleague who could speak more freely. Check your organization’s policy regarding references. Some strict organizations do not allow employees to give references. Find out what is available to you because the reference-checking process is critical to the job search process.

Finally, plan for how you will leave your current job gracefully. Two weeks’ notice is a national standard, but this varies by industry, company, and job. If you have a specialized function, a senior role, or are currently on a long-term assignment, it might be expected that you will give more notice than two weeks. You might be expected to train your incumbent, or even help find this person. Unless you have an employment contract (rare and typically reserved for the most executive-level jobs), remember that most jobs are employment at will, so you can leave at any time with no notice. However, you want to exit gracefully so you maintain good relationships with your organization and colleagues. People move around in their careers, and in the future you may find yourself working with some of the same people.

Getting any one job is only one step to building a career. Your career is made up of many jobs where you will add to your skills, experience, and relationships. At the same time, your career is built one job at a time. You need to do well in the job you have currently, not just look to more responsibility before you have mastered the current ones. Focus on doing your current job well. Cultivate mentors and professional relationships with people who are knowledgeable and supportive. Be proactive about steering your career forward by getting regular performance feedback and asking for promotions and raises when warranted.

Know how to continue to do well on the job, even in difficult economic times and through challenging work situations. Lean on your professional relationships, but also do your own research on company policy and talk with human resources (HR). Doing well in the work environment depends heavily on your ability to manage relationships, so focus on your communication skills and ability to set boundaries.

Remember to have a life outside your professional work. Do not neglect personal relationships. Take care of your health and personal finances. Pursue hobbies and interests that don’t have to benefit your career.

Finally, building a career isn’t just about getting a job, but you also must know when to leave your job. Be clear about your objectives for your next position. Don’t forget to explore opportunities within your current organization, but don’t be afraid to revisit the six steps of the job search and find another position. Remember to maintain your obligations in your current job while you are looking and to exit gracefully. Then start identifying your target, create a compelling marketing campaign, conduct in-depth research.…