“Baltimore Students Lead Rally for Better School Facilities,” the headline said. On a crisp fall day, some 240 students, teachers, and parents held a rally at City Hall in Baltimore, Maryland, to call for massive improvements in the city’s deteriorating schools. According to the news article, students displayed photos of decaying conditions in their schools and “spoke of horrific learning conditions: roaches, rodents, decaying roofs, rotting walls, sewage overflows, and inadequate heating and cooling systems.” A high school senior said, “It’s not that the teachers aren’t the best, because they are, and it’s not that the students are misbehaving. That’s not it. We have buildings that you can’t do anything with.” The president of Baltimore’s City Council agreed. “We owe it to our students to have state-of-the-art schools,” he said. “Our school buildings are conducive to our kids’ learning. If they go into school buildings that don’t have running water, where bathrooms aren’t functioning properly, with outdated furniture and no books in the library, then what do we expect from our kids?”

Source: Burris, 2011Burris, J. (2011, November 3). Baltimore students lead rally for better school facilities. The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved from http://articles.baltimoresun.com/2011-11-03/news/bs-md-ci-rally-facilities-20111103_1_school-buildings-baltimore-students-city-schools.

Charles Dickens’s majestic novel, A Tale of Two Cities, begins with this unforgettable passage: “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to heaven, we were all going direct the other way.”

These words are timeless, and they certainly apply to the US education system today. In many ways it is the best of systems, but in many ways it is also the worst of systems. It teaches wisdom, but its many problems smack of foolishness. It fills many people with hope, but it also fills many people with despair. Some students have everything before them, but many also have nothing before them. In the wealthiest nation on the face of the earth, students in one of America’s largest cities, Baltimore, attend schools filled with roaches and rodents and reeking of sewage. They are hardly alone, as students in cities across the nation could easily speak of similar ills. If Dickens were alive today, he might well look at our schools and conclude that “we were all going direct the other way.”

Education is one of our most important social institutions. Youngsters and adolescents spend most of their weekday waking hours in school, doing homework, or participating in extracurricular activities, and many then go on to college. People everywhere care deeply about what happens in our nation’s schools, and issues about the schools ignite passions across the political spectrum. Yet, as the opening news story about Baltimore’s schools illustrates, many schools are poorly equipped to prepare their students for the complex needs of today’s world.

This chapter’s discussion of education begins with an overview of education in the United States and then turns to sociological perspectives on education. The remainder of the chapter discusses education in today’s society. This discussion highlights education as a source and consequence of various social inequalities and examines several key issues affecting the nation’s schools and the education of its children.

EducationThe social institution through which a society teaches its members the skills, knowledge, norms, and values they need to learn to become good, productive members of their society. is the social institution through which a society teaches its members the skills, knowledge, norms, and values they need to learn to become good, productive members of their society. As this definition makes clear, education is an important part of socialization. Education is both formal and informal. Formal educationLearning that occurs in schools under teachers, principals, and other specially trained professionals. is often referred to as schooling, and as this term implies, it occurs in schools under teachers, principals, and other specially trained professionals. Informal educationLearning that occurs outside the schools, traditionally in the home. may occur almost anywhere, but for young children it has traditionally occurred primarily in the home, with their parents as their instructors. Day care has become an increasingly popular venue in industrial societies for young children’s instruction, and education from the early years of life is thus more formal than it used to be.

Education in early America was only rarely formal. During the colonial period, the Puritans in what is now Massachusetts required parents to teach their children to read and also required larger towns to have an elementary school, where children learned reading, writing, and religion. In general, though, schooling was not required in the colonies, and only about 10 percent of colonial children, usually just the wealthiest, went to school, although others became apprentices (Urban & Wagoner, 2008).Urban, W. J., & Wagoner, J. L., Jr. (2008). American education: A history (4th ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

To help unify the nation after the Revolutionary War, textbooks were written to standardize spelling and pronunciation and to instill patriotism and religious beliefs in students. At the same time, these textbooks included negative stereotypes of Native Americans and certain immigrant groups. The children going to school continued primarily to be those from wealthy families. By the mid-1800s, a call for free, compulsory education had begun, and compulsory education became widespread by the end of the century. This was an important development, as children from all social classes could now receive a free, formal education. Compulsory education was intended to further national unity and to teach immigrants “American” values. It also arose because of industrialization, as an industrial economy demanded reading, writing, and math skills much more than an agricultural economy had.

Free, compulsory education, of course, applied only to primary and secondary schools. Until the mid-1900s, very few people went to college, and those who did typically came from fairly wealthy families. After World War II, however, college enrollments soared, and today more people are attending college than ever before, even though college attendance is still related to social class, as we shall discuss shortly.

An important theme emerges from this brief history: Until very recently in the record of history, formal schooling was restricted to wealthy males. This means that boys who were not white and rich were excluded from formal schooling, as were virtually all girls, whose education was supposed to take place informally at home. Today, as we will see, race, ethnicity, social class, and, to some extent, gender continue to affect both educational achievement and the amount of learning occurring in schools.

In colonial America, only about 10 percent of children went to school, and these children tended to come from wealthy families. After the Revolutionary War, new textbooks helped standardize spelling and pronunciation and promote patriotism and religious beliefs, but these textbooks also included negative stereotypes of Native Americans.

Image courtesy of Joel Dorman Steele and Esther Baker Steele, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Spinninginthecolonialkitchen.jpg.

Education in the United States is a massive social institution involving millions of people and billions of dollars. More than 75 million people, almost one-fourth of the US population, attend school at all levels. This number includes 40 million in grades pre-K through eighth grade, 16 million in high school, and 20 million in college (including graduate and professional school). They attend some 132,000 elementary and secondary schools and about 4,200 two-year and four-year colleges and universities and are taught by about 4.8 million teachers and professors (US Census Bureau, 2012).US Census Bureau. (2012). Statistical abstract of the United States: 2012. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab.

About 65 percent of US high school graduates enroll in college the following fall. This is a very high figure by international standards, as college in many other industrial nations is reserved for the very small percentage of the population who pass rigorous entrance exams. They are the best of the brightest in their nations, whereas higher education in the United States is open to all who graduate high school. Even though that is true, our chances of achieving a college degree are greatly determined at birth, as social class and race and ethnicity substantially affect who goes to college. They affect whether students drop out of high school, in which case they do not go on to college; they affect the chances of getting good grades in school and good scores on college entrance exams; they affect whether a family can afford to send its children to college; and they affect the chances of staying in college and obtaining a degree versus dropping out. For all these reasons, educational attainmentHow far one gets in school, which has been shown to depend heavily on family income and race/ethnicity.—how far one gets in school—depends heavily on family income and race/ethnicity (Tavernise, 2012).Tavernise, S. (2012, February 10). Education gap grows between rich and poor, studies say. New York Times, p. A1. Family income, in fact, makes a much larger difference in educational attainment than it did during the 1960s.

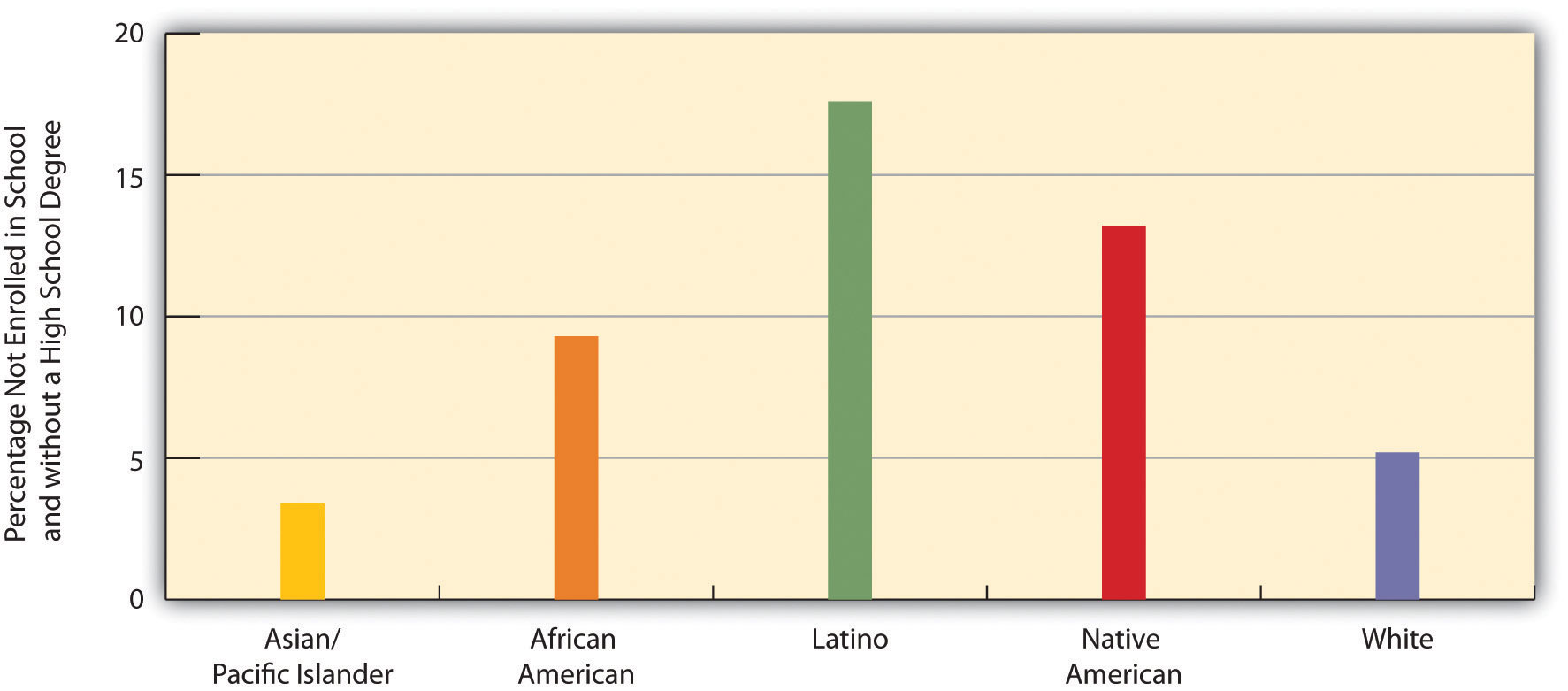

Government data readily show the effects of family income and race/ethnicity on educational attainment. Let’s first look at how race and ethnicity affect the likelihood of dropping out of high school. Figure 11.1 "Race, Ethnicity, and High School Dropout Rate, Persons Ages 16–24, 2009 (Percentage Not Enrolled in School and without a High School Degree)" shows the percentage of people ages 16–24 who are not enrolled in school and who have not received a high school degree. The dropout rate is highest for Latinos and Native Americans and lowest for Asians and whites.

Figure 11.1 Race, Ethnicity, and High School Dropout Rate, Persons Ages 16–24, 2009 (Percentage Not Enrolled in School and without a High School Degree)

Source: Aud, S., Hussar, W., Kena, G., Bianco, K., Frohlich, L., Kemp, J., et al. (2011). The condition of education 2011. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics.

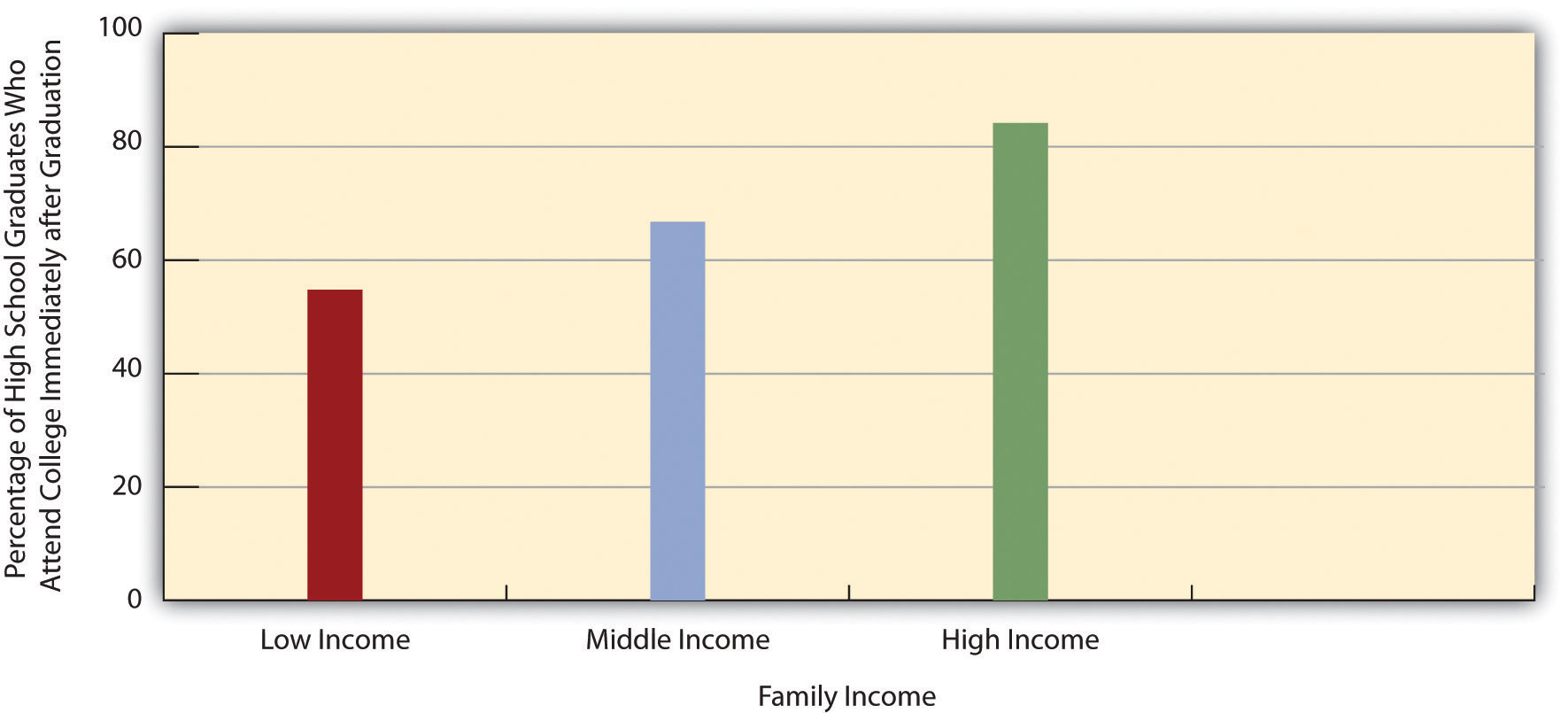

Now let’s look at how family income affects the likelihood of attending college, a second benchmark of educational attainment. Figure 11.2 "Family Income and Percentage of High School Graduates Who Attend College Immediately after Graduation, 2009" shows the relationship between family income and the percentage of high school graduates who enroll in college immediately following graduation: Students from families in the highest income bracket are more likely than those in the lowest bracket to attend college. This “income gap” in college entry has become larger in recent decades (Bailey & Dynarski, 2011).Bailey, M. J., & Dynarski, S. (2011). Gains and gaps: Changing inequality in US college entry and completion. Ann Arbor, MI: Population Studies Center.

Figure 11.2 Family Income and Percentage of High School Graduates Who Attend College Immediately after Graduation, 2009

Source: Aud, S., Hussar, W., Kena, G., Bianco, K., Frohlich, L., Kemp, J., et al. (2011). The condition of education 2011. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics.

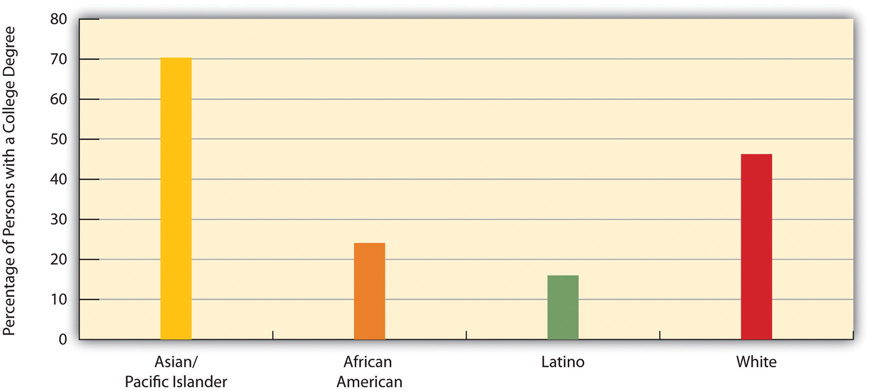

Finally, let’s examine how race and ethnicity affect the likelihood of obtaining a college degree, a third benchmark of educational attainment. Figure 11.3 "Race, Ethnicity, and Percentage of Persons Ages 25 or Older with a Four-Year College Degree, 2010" shows the relationship between race/ethnicity and the percentage of persons 25 or older who have a bachelor’s or master’s degree. This relationship is quite strong, with African Americans and Latinos least likely to have a degree, and whites and especially Asians/Pacific Islanders most likely to have a degree.

Figure 11.3 Race, Ethnicity, and Percentage of Persons Ages 25 or Older with a Four-Year College Degree, 2010

Source: Aud, S., Hussar, W., Kena, G., Bianco, K., Frohlich, L., Kemp, J., et al. (2011). The condition of education 2011. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics.

Why do African Americans and Latinos have lower educational attainment? Four factors are commonly cited: (a) the underfunded and otherwise inadequate schools that children in both groups often attend; (b) the higher poverty of their families and lower education of their parents that often leave children ill prepared for school even before they enter kindergarten; (c) racial discrimination; and (d) the fact that African American and Latino families are especially likely to live in very poor neighborhoods (Ballantine & Hammack, 2012; Yeung & Pfeiffer, 2009).Ballantine, J. H., & Hammack, F. M. (2012). The sociology of education: A systematic analysis (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; Yeung, W.-J. J., & Pfeiffer, K. M. (2009). The black-white test score gap and early home environment. Social Science Research, 38(2), 412–437.

The last two factors, racial discrimination and residence in high-poverty neighborhoods, need additional explanation. At least three forms of racial discrimination impair educational attainment (Mickelson, 2003).Mickelson, R. A. (2003). When are racial disparities in education the result of racial discrimination? A social science perspective. Teachers College Record, 105, pp. 1052–1086. The first form involves tracking. As we discuss later, students tracked into vocational or general curricula tend to learn less and have lower educational attainment than those tracked into a faster-learning, academic curriculum. Because students of color are more likely to be tracked “down” rather than “up,” their school performance and educational attainment suffer.

The second form of racial discrimination involves school discipline. As we also discuss later, students of color are more likely than white students to be suspended, expelled, or otherwise disciplined for similar types of misbehavior. Because such discipline again reduces school performance and educational attainment, this form of discrimination helps explain the lower attainment of African American and Latino students.

The third form involves teachers’ expectations of students. As our later discussion of the symbolic interactionist perspective on education examines further, teachers’ expectations of students affect how much students learn. Research finds that teachers have lower expectations for their African American and Latino students, and that these expectations help to lower how much these students learn.

Turning to residence in high-poverty neighborhoods, it may be apparent that poor neighborhoods have lower educational attainment because they have inadequate schools, but poor neighborhoods matter for reasons beyond their schools’ quality (Kirk & Sampson, 2011; Wodtke, Harding, & Elwert, 2011).Kirk, D. S., & Sampson, R. J. (2011). Crime and the production of safe schools. In G. J. Duncan & R. J. Murnane (Eds.), Whither opportunity?: Rising inequality, schools, and children’s life chances (pp. 397–418). New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; Wodtke, G. T., Harding, D. J., & Elwert, F. (2011). Neighborhood effects in temporal perspective: The impact of long-term exposure to concentrated disadvantage on high school graduation. American Sociological Review, 76(5), 713–736. First, because many adults in these neighborhoods are high school dropouts and/or unemployed, children in these neighborhoods lack adult role models for educational attainment. Second, poor neighborhoods tend to be racially and ethnically segregated. Latino children in these neighborhoods are less likely to speak English well because they lack native English-speaking friends, and African American children are more likely to speak “black English” than conventional English; both language problems impede school success.

Third, poor neighborhoods have higher rates of violence and other deviant behaviors than wealthier neighborhoods. Children in these neighborhoods thus are more likely to experience high levels of stress, to engage in these behaviors themselves (which reduces their attention and commitment to their schooling), and to be victims of violence (which increases their stress and can impair their neurological development). Crime in these neighborhoods also tends to reduce teacher commitment and parental involvement in their children’s schooling. Finally, poor neighborhoods are more likely to have environmental problems such as air pollution and toxic levels of lead paint; these problems lead to asthma and other health problems among children (as well as adults), which impairs the children’s ability to learn and do well in school.

For all these reasons, then, children in poor neighborhoods are at much greater risk for lower educational attainment. As a recent study of this risk concluded, “Sustained exposure to disadvantaged neighborhoods…throughout the entire childhood life course has a devastating impact on the chances of graduating from high school” (Wodtke et al., 2011, p. 731).Wodtke, G. T., Harding, D. J., & Elwert, F. (2011). Neighborhood effects in temporal perspective: The impact of long-term exposure to concentrated disadvantage on high school graduation. American Sociological Review, 76(5), 713–736. If these neighborhoods are not improved, the study continued, “concentrated neighborhood poverty will likely continue to hamper the development of future generations of children” (Wodtke et al., 2011, p. 733).Wodtke, G. T., Harding, D. J., & Elwert, F. (2011). Neighborhood effects in temporal perspective: The impact of long-term exposure to concentrated disadvantage on high school graduation. American Sociological Review, 76(5), 713–736.

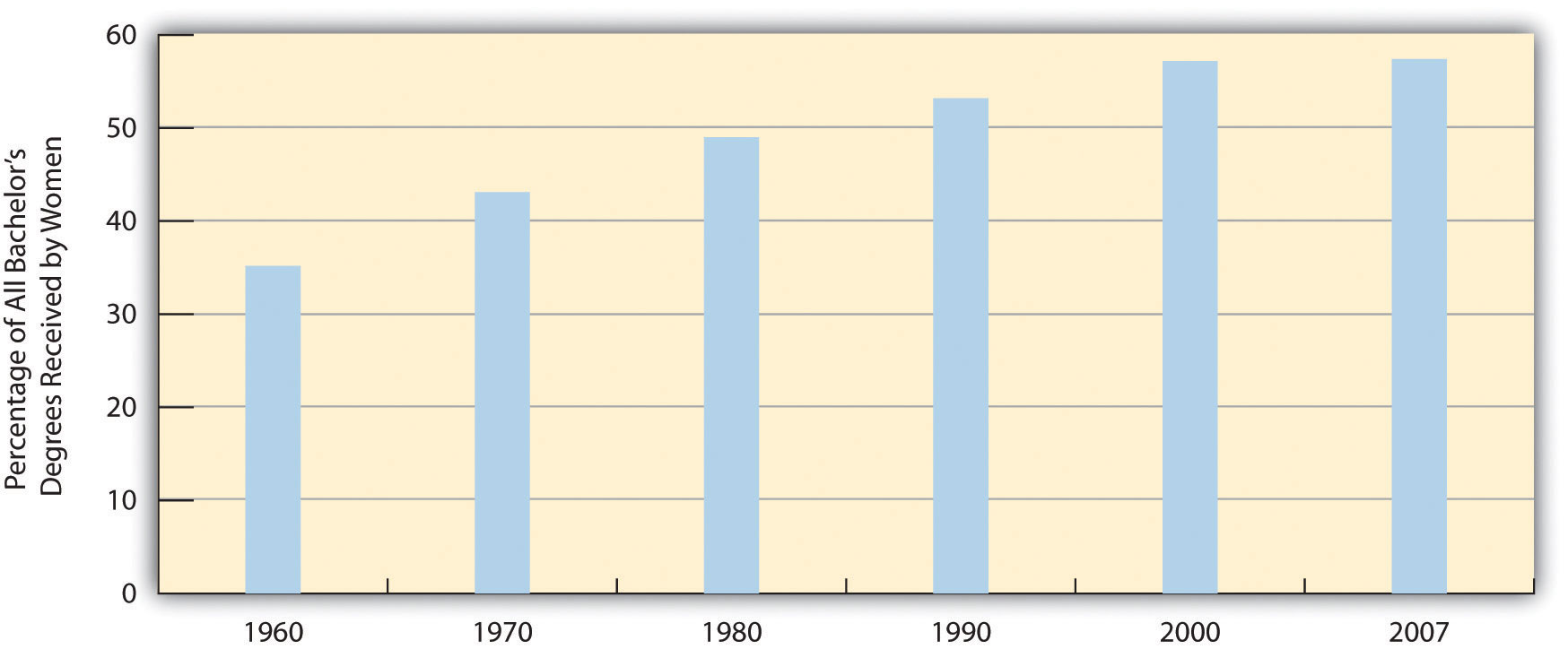

Gender also affects educational attainment. If we do not take age into account, slightly more men than women have a college degree: 30.3 percent of men and 29.6 percent of women. This difference reflects the fact that women were less likely than men in earlier generations to go to college. But today there is a gender difference in the other direction: Women now earn more than 57 percent of all bachelor’s degrees, up from just 35 percent in 1960 (see Figure 11.4 "Percentage of All Bachelor’s Degrees Received by Women, 1960–2009"). This difference reflects the fact that females are more likely than males to graduate high school, to attend college after high school graduation, and to obtain a degree after starting college (Bailey & Dynarski, 2011).Bailey, M. J., & Dynarski, S. (2011). Gains and gaps: Changing inequality in US college entry and completion. Ann Arbor, MI: Population Studies Center.

Figure 11.4 Percentage of All Bachelor’s Degrees Received by Women, 1960–2009

Source: Data from US Census Bureau. (2012). Statistical abstract of the United States: 2012. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab.

Have you ever applied for a job that required a high school degree? Are you going to college in part because you realize you will need a college degree for a higher-paying job? As these questions imply, the United States is a credential societyA society in which higher education is seen as evidence of the attainment of the needed knowledge and skills for various kinds of jobs. (Collins, 1979).Collins, R. (1979). The credential society: An historical sociology of education and stratification. New York, NY: Academic Press. This means at least two things. First, a high school or college degree (or beyond) indicates that a person has acquired the needed knowledge and skills for various jobs. Second, a degree at some level is a requirement for most jobs. As you know full well, a college degree today is a virtual requirement for a decent-paying job. The ante has been upped considerably over the years: In earlier generations, a high school degree, if even that, was all that was needed, if only because so few people graduated from high school to begin with. With so many people graduating from high school today, a high school degree is not worth as much. Then too, today’s society increasingly requires skills and knowledge that only a college education brings.

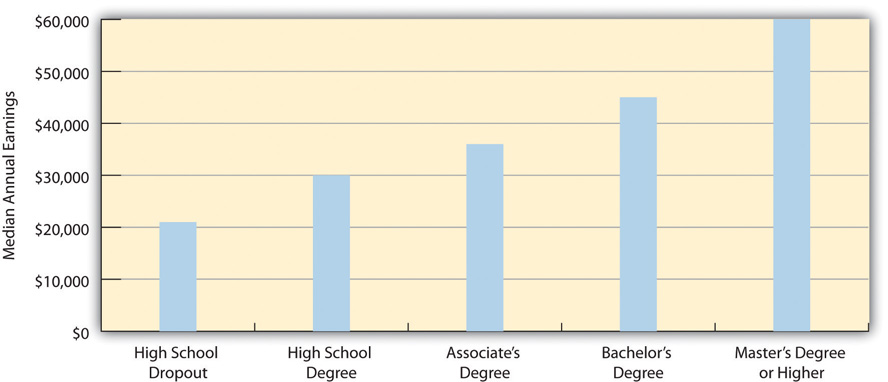

A credential society also means that people with more formal education achieve higher incomes. Annual earnings are indeed much higher for people with more education (see Figure 11.5 "Educational Attainment and Median Annual Earnings, Ages 25–34, 2009"). As earlier chapters indicated, gender and race/ethnicity affect the payoff we get from our education, but education itself still makes a huge difference for our incomes.

Figure 11.5 Educational Attainment and Median Annual Earnings, Ages 25–34, 2009

Source: Aud, S., Hussar, W., Kena, G., Bianco, K., Frohlich, L., Kemp, J., et al. (2011). The condition of education 2011. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics.

Beyond income, education also affects at what age people tend to die. Simply put, people with higher levels of education tend to die later in life, and those with lower levels tend to die earlier (Miech, Pampel, Kim, & Rogers, 2011).Miech, R., Pampel, F., Kim, J., & Rogers, R. G. (2011). Education and mortality: The role of widening and narrowing disparities. American Sociological Review, 76, 913–934. The reasons for this disparity are complex, but two reasons stand out. First, more highly educated people are less likely to smoke and engage in other unhealthy activities, and they are more likely to exercise and to engage in other healthy activities and also to eat healthy diets. Second, they have better access to high-quality health care.

The United States has many of the top colleges and universities and secondary schools in the world, and many of the top professors and teachers. In these respects, the US education system is “the best of systems.” But in other respects, it is “the worst of systems.” When we compare educational attainment in the United States to that in the world’s other democracies, the United States lags behind its international peers.

Differences in the educational systems of the world’s democracies make exact comparisons difficult, but one basic measure of educational attainment is the percentage of a nation’s population that has graduated high school. A widely cited comparison involves the industrial nations that are members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Of the twenty-eight nations for which OECD has high school graduation data, the United States ranks only twenty-first, with a graduation rate of 76 percent (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2011).Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2011). How many students finish secondary education? Retrieved November 10, 2011, from http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/62/3/48630687.pdf. In contrast, several nations, including Finland, Ireland, Norway, Portugal, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom have graduation rates of at least 90 percent. If we limit the comparison to the OECD nations that compose the world’s wealthy democracies (see Chapter 2 "Poverty") to which the United States is most appropriately compared, the United States ranks only thirteenth out of sixteen such nations.

OECD also collects and publishes data on proficiency in mathematics, reading, and science among 15-year-olds in its member nations (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2010).Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2010). PISA 2009 results: What students know and can do—Student performance in reading, mathematics and science (Vol. 1). Paris, France: Author. In reading and science, the United States ranks only at the average for all OECD nations, while the US score for mathematics ranks below the OECD average. Compared to their counterparts in other industrial nations, then, American 15-year-olds are only average or below average for these three important areas of study. Taking into account high school graduation rates and these proficiency rankings, the United States is far from the world leader in the quality of education. The Note 11.8 "Lessons from Other Societies" box examines what the United States might learn from the sterling example of Finland’s education system.

Successful Schooling in Finland

Finland is widely regarded as having perhaps the top elementary and secondary education system in the world. Its model of education offers several important lessons for US education. As a recent analysis of Finland’s schools put it, “The country’s achievements in education have other nations doing their homework.”

To understand the lessons to be learned from Finland, we should go back several decades to the 1970s, when Finland’s education system was below par, with its students scoring below the international average in mathematics and science. Moreover, urban schools in Finland outranked rural schools, and wealthy students performed much better than low-income students. Today, Finnish students rank at the top in international testing, and low-income students do almost as well as wealthy students.

Finland’s education system ranks so highly today because it took several measures to improve its education system. First, and perhaps most important, Finland raised teachers’ salaries, required all teachers to have a three-year master’s degree, and paid all costs, including a living stipend, for the graduate education needed to achieve this degree. These changes helped to greatly increase the number of teachers, especially the number of highly qualified teachers, and Finland now has more teachers for every 1,000 residents than does the United States. Unlike the United States, teaching is considered a highly prestigious profession in Finland, and the application process to become a teacher is very competitive. The college graduates who apply for one of Finland’s eight graduate programs in teaching typically rank in the top 10 percent of their class, and only 5–15 percent of their applications are accepted. A leading Finnish educator observed, “It’s more difficult getting into teacher education than law or medicine.” In contrast, US students who become teachers tend to have lower SAT scores than those who enter other professions, they only need a four-year degree, and their average salaries are lower than other professionals with a similar level of education.

Second, Finland revamped its curriculum to emphasize critical thinking skills, reduced the importance of scores on standardized tests and then eliminated standardized testing altogether, and eliminated academic tracking before tenth grade. Unlike the United States, Finland no longer ranks students, teachers, or schools according to scores on standardized tests because these tests are no longer given.

Third, Finland built many more schools to enable the average school to have fewer students. Today the typical school has fewer than three hundred students, and class sizes are smaller than those found in the United States.

Fourth, Finland increased funding of its schools so that its schools are now well maintained and well equipped. Whereas many US schools are decrepit, Finnish schools are decidedly in good repair.

Finally, Finland provided free medical and dental care for children and their families and expanded other types of social services, including three years of paid maternity leave and subsidized day care, as the country realized that children’s health and home environment play critical roles in their educational achievement.

These and other changes helped propel Finland’s education system to a leading position among the world’s industrial nations. As the United States ponders how best to improve its own education system, it may have much to learn from Finland’s approach to how children should learn.

Sources: Abrams, 2011; Anderson, 2011; Eggers & Calegari, 2011; Hancock, 2011; Ravitch, 2012; Sahlberg, 2011Abrams, S. E. (2011, January 28). The children must play: What the United States could learn from Finland about education reform. The New Republic. Retrieved from http://www.tnr.com/article/politics/82329/education-reform-Finland-US; Anderson, J. (2011, December 13). From Finland, an intriguing school-reform model. New York Times, p. A33; Eggers, D., & Calegari, N. C. (2011, May 1). The high cost of low teacher salaries. New York Times, p. WK12; Hancock, L. (2011, September). Why are Finland’s schools successful? Smithsonian. Retrieved from http://www.smithsonianmag.com/people-places/Why-Are-Finlands-Schools-Successful.html?c=y&story=fullstory; Ravitch, D. (2012, March 8). Schools we can envy. The New York Review of Books. Retrieved from http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2012/mar/08/schools-we-can-envy/; Sahlberg, P. (2011). Finnish lessons: What can the world learn from educational change in Finland? New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

The major sociological perspectives on education fall nicely into the functional, conflict, and symbolic interactionist approaches (Ballantine & Hammack, 2012).Ballantine, J. H., & Hammack, F. M. (2012). The sociology of education: A systematic analysis (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Table 11.1 "Theory Snapshot" summarizes what these approaches say.

Table 11.1 Theory Snapshot

| Theoretical perspective | Major assumptions |

|---|---|

| Functionalism | Education serves several functions for society. These include (a) socialization, (b) social integration, (c) social placement, and (d) social and cultural innovation. Latent functions include child care, the establishment of peer relationships, and lowering unemployment by keeping high school students out of the full-time labor force. Problems in the educational institution harm society because all these functions cannot be completely fulfilled. |

| Conflict theory | Education promotes social inequality through the use of tracking and standardized testing and the impact of its “hidden curriculum.” Schools differ widely in their funding and learning conditions, and this type of inequality leads to learning disparities that reinforce social inequality. |

| Symbolic interactionism | This perspective focuses on social interaction in the classroom, on the playground, and in other school venues. Specific research finds that social interaction in schools affects the development of gender roles and that teachers’ expectations of pupils’ intellectual abilities affect how much pupils learn. Certain educational problems have their basis in social interaction and expectations. |

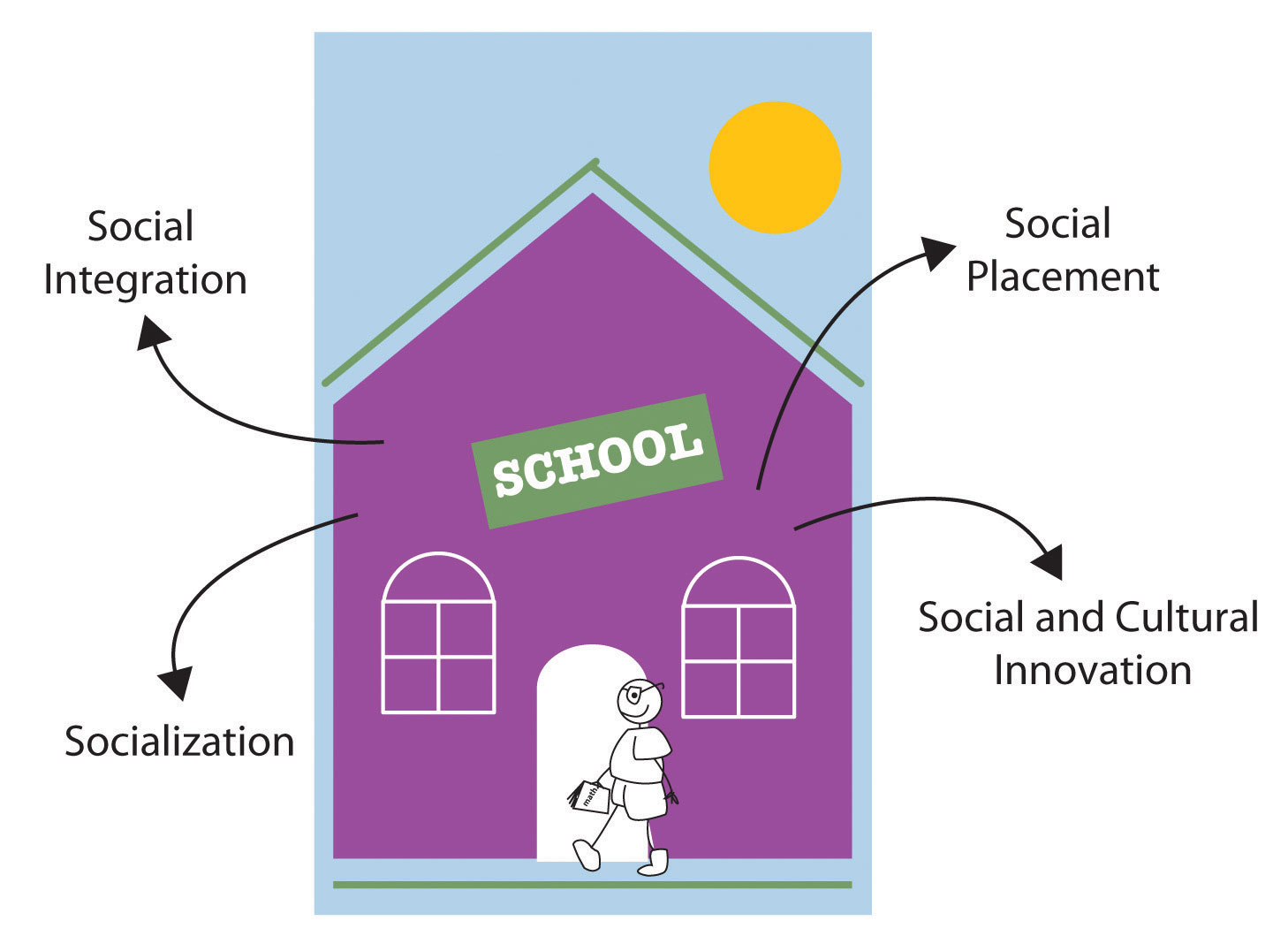

Functional theory stresses the functions that education serves in fulfilling a society’s various needs. Perhaps the most important function of education is socialization. If children are to learn the norms, values, and skills they need to function in society, then education is a primary vehicle for such learning. Schools teach the three Rs (reading, ’riting, ’rithmetic), as we all know, but they also teach many of the society’s norms and values. In the United States, these norms and values include respect for authority, patriotism (remember the Pledge of Allegiance?), punctuality, and competition (for grades and sports victories).

A second function of education is social integration. For a society to work, functionalists say, people must subscribe to a common set of beliefs and values. As we saw, the development of such common views was a goal of the system of free, compulsory education that developed in the nineteenth century. Thousands of immigrant children in the United States today are learning English, US history, and other subjects that help prepare them for the workforce and integrate them into American life.

A third function of education is social placement. Beginning in grade school, students are identified by teachers and other school officials either as bright and motivated or as less bright and even educationally challenged. Depending on how they are identified, children are taught at the level that is thought to suit them best. In this way, they are presumably prepared for their later station in life. Whether this process works as well as it should is an important issue, and we explore it further when we discuss school tracking later in this chapter.

Social and cultural innovation is a fourth function of education. Our scientists cannot make important scientific discoveries and our artists and thinkers cannot come up with great works of art, poetry, and prose unless they have first been educated in the many subjects they need to know for their chosen path.

Figure 11.6 The Functions of Education

Schools ideally perform many important functions in modern society. These include socialization, social integration, social placement, and social and cultural innovation.

Education also involves several latent functions, functions that are by-products of going to school and receiving an education rather than a direct effect of the education itself. One of these is child care: Once a child starts kindergarten and then first grade, for several hours a day the child is taken care of for free. The establishment of peer relationships is another latent function of schooling. Most of us met many of our friends while we were in school at whatever grade level, and some of those friendships endure the rest of our lives. A final latent function of education is that it keeps millions of high school students out of the full-time labor force. This fact keeps the unemployment rate lower than it would be if they were in the labor force.

Because education serves so many manifest and latent functions for society, problems in schooling ultimately harm society. For education to serve its many functions, various kinds of reforms are needed to make our schools and the process of education as effective as possible.

Conflict theory does not dispute the functions just described. However, it does give some of them a different slant by emphasizing how education also perpetuates social inequality (Ballantine & Hammack, 2012).Ballantine, J. H., & Hammack, F. M. (2012). The sociology of education: A systematic analysis (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. One example of this process involves the function of social placement. When most schools begin tracking their students in grade school, the students thought by their teachers to be bright are placed in the faster tracks (especially in reading and arithmetic), while the slower students are placed in the slower tracks; in high school, three common tracks are the college track, vocational track, and general track.

Such tracking does have its advantages; it helps ensure that bright students learn as much as their abilities allow them, and it helps ensure that slower students are not taught over their heads. But conflict theorists say that tracking also helps perpetuate social inequality by locking students into faster and lower tracks. Worse yet, several studies show that students’ social class and race and ethnicity affect the track into which they are placed, even though their intellectual abilities and potential should be the only things that matter: White, middle-class students are more likely to be tracked “up,” while poorer students and students of color are more likely to be tracked “down.” Once they are tracked, students learn more if they are tracked up and less if they are tracked down. The latter tend to lose self-esteem and begin to think they have little academic ability and thus do worse in school because they were tracked down. In this way, tracking is thought to be good for those tracked up and bad for those tracked down. Conflict theorists thus say that tracking perpetuates social inequality based on social class and race and ethnicity (Ansalone, 2010).Ansalone, G. (2010). Tracking: Educational differentiation or defective strategy. Educational Research Quarterly, 34(2), 3–17.

Conflict theorists add that standardized tests are culturally biased and thus also help perpetuate social inequality (Grodsky, Warren, & Felts, 2008).Grodsky, E., Warren, J. R., & Felts, E. (2008). Testing and social stratification in American education. Annual Review of Sociology, 34(1), 385–404. According to this criticism, these tests favor white, middle-class students whose socioeconomic status and other aspects of their backgrounds have afforded them various experiences that help them answer questions on the tests.

A third critique of conflict theory involves the quality of schools. As we will see later in this chapter, US schools differ mightily in their resources, learning conditions, and other aspects, all of which affect how much students can learn in them. Simply put, schools are unequal, and their very inequality helps perpetuate inequality in the larger society. Children going to the worst schools in urban areas face many more obstacles to their learning than those going to well-funded schools in suburban areas. Their lack of learning helps ensure they remain trapped in poverty and its related problems.

In a fourth critique, conflict theorists say that schooling teaches a hidden curriculumA set of values and beliefs learned in school that support the status quo, including the existing social hierarchy., by which they mean a set of values and beliefs that support the status quo, including the existing social hierarchy (Booher-Jennings, 2008).Booher-Jennings, J. (2008). Learning to label: Socialisation, gender, and the hidden curriculum of high-stakes testing. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 29, 149–160. Although no one plots this behind closed doors, our schoolchildren learn patriotic values and respect for authority from the books they read and from various classroom activities.

A final critique is historical and concerns the rise of free, compulsory education during the nineteenth century (Cole, 2008).Cole, M. (2008). Marxism and educational theory: Origins and issues. New York, NY: Routledge. Because compulsory schooling began in part to prevent immigrants’ values from corrupting “American” values, conflict theorists see its origins as smacking of ethnocentrism (the belief that one’s own group is superior to another group). They also criticize its intention to teach workers the skills they needed for the new industrial economy. Because most workers were very poor in this economy, these critics say, compulsory education served the interests of the upper/capitalist class much more than it served the interests of workers.

Symbolic interactionist studies of education examine social interaction in the classroom, on the playground, and in other school venues. These studies help us understand what happens in the schools themselves, but they also help us understand how what occurs in school is relevant for the larger society. Some studies, for example, show how children’s playground activities reinforce gender-role socialization. Girls tend to play more cooperative games, while boys play more competitive sports (Thorne, 1993)Thorne, B. (1993). Gender play: Girls and boys in school. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. (see Chapter 4 "Gender Inequality").

Assessing the Impact of Small Class Size

Do elementary school students fare better if their classes have fewer students rather than more students? It is not easy to answer this important question, because any differences found between students in small classes and those in larger classes might not necessarily reflect class size. Rather, they may reflect other factors. For example, perhaps the most motivated, educated parents ask that their child be placed in a smaller class and that their school goes along with this request. Perhaps teachers with more experience favor smaller classes and are able to have their principals assign them to these classes, while new teachers are assigned larger classes. These and other possibilities mean that any differences found between the two class sizes might reflect the qualities and skills of students and/or teachers in these classes, and not class size itself.

For this reason, the ideal study of class size would involve random assignment of both students and teachers to classes of different size. (Recall that Chapter 1 "Understanding Social Problems" discusses the benefits of random assignment.) Fortunately, a notable study of this type exists.

The study, named Project STAR (Student/Teacher Achievement Ratio), began in Tennessee in 1985 and involved 79 public schools and 11,600 students and 1,330 teachers who were all randomly assigned to either a smaller class (13–17 students) or a larger class (22–25 students). The random assignment began when the students entered kindergarten and lasted through third grade; in fourth grade, the experiment ended, and all the students were placed into the larger class size. The students are now in their early thirties, and many aspects of their educational and personal lives have been followed since the study began.

Some of the more notable findings of this multiyear study include the following:

Why did small class size have these benefits? Two reasons seem likely. First, in a smaller class, there are fewer students to disrupt the class by talking, fighting, or otherwise taking up the teacher’s time. More learning can thus occur in smaller classes. Second, kindergarten teachers are better able to teach noncognitive skills (cooperating, listening, sitting still) in smaller classes, and these skills can have an impact many years later.

Regardless of the reasons, it was the experimental design of Project STAR that enabled its findings to be attributed to class size rather than to other factors. Because small class size does seem to help in many ways, the United States should try to reduce class size in order to improve student performance and later life outcomes.

Sources: Chetty et al., 2011; Schanzenbach, 2006Chetty, R., Friedman, J. N., Hilger, N., Saez, E., Schanzenbach, D. W., & Yagan, D. (2011). How does your kindergarten classroom affect your earnings? Evidence from Project STAR. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 126, 1593–1660; Schanzenbach, D. W. (2006). What have researchers learned from Project STAR? (Harris School Working Paper—Series 06.06).

Another body of research shows that teachers’ views about students can affect how much the students learn. When teachers think students are smart, they tend to spend more time with these students, to call on them, and to praise them when they give the right answer. Not surprisingly, these students learn more because of their teachers’ behavior. But when teachers think students are less bright, they tend to spend less time with these students and to act in a way that leads them to learn less. Robert Rosenthal and Lenore Jacobson (1968)Rosenthal, R., & Jacobson, L. (1968). Pygmalion in the classroom. New York, NY: Holt. conducted a classic study of this phenomenon. They tested a group of students at the beginning of the school year and told their teachers which students were bright and which were not. They then tested the students again at the end of the school year. Not surprisingly, the bright students had learned more during the year than the less bright ones. But it turned out that the researchers had randomly decided which students would be designated bright and less bright. Because the “bright” students learned more during the school year without actually being brighter at the beginning, their teachers’ behavior must have been the reason. In fact, their teachers did spend more time with them and praised them more often than was true for the “less bright” students. This process helps us understand why tracking is bad for the students tracked down.

Other research in the symbolic interactionist tradition focuses on how teachers treat girls and boys. Many studies find that teachers call on and praise boys more often (Jones & Dindia, 2004).Jones, S. M., & Dindia, K. (2004). A meta-analystic perspective on sex equity in the classroom. Review of Educational Research, 74, 443–471. Teachers do not do this consciously, but their behavior nonetheless sends an implicit message to girls that math and science are not for them and that they are not suited to do well in these subjects. This body of research has stimulated efforts to educate teachers about the ways in which they may unwittingly send these messages and about strategies they could use to promote greater interest and achievement by girls in math and science (Battey, Kafai, Nixon, & Kao, 2007).Battey, D., Kafai, Y., Nixon, A. S., & Kao, L. L. (2007). Professional development for teachers on gender equity in the sciences: Initiating the conversation. Teachers College Record, 109(1), 221–243.

The elementary (K–8) and secondary (9–12) education system today faces many issues and problems of interest not just to educators and families but also to sociologists and other social scientists. We cannot discuss all these issues here, but we will highlight some of the most interesting and important.

Earlier we mentioned that schools differ greatly in their funding, their conditions, and other aspects. Noted author and education critic Jonathan Kozol refers to these differences as “savage inequalities,” to quote the title of one of his books (Kozol, 1991).Kozol, J. (1991). Savage inequalities: Children in America’s schools. New York, NY: Crown. Kozol’s concern over inequality in the schools stemmed from his experience as a young teacher in a public elementary school in a Boston inner-city neighborhood in the 1960s. Kozol was shocked to see that his school was literally falling apart. The building itself was decrepit, with plaster falling off the walls and bathrooms and other facilities substandard. Classes were large, and the school was so overcrowded that Kozol’s fourth-grade class had to meet in an auditorium, which it shared with another class, the school choir, and, for a time, a group of students practicing for the Christmas play. Kozol’s observations led to the writing of his first award-winning book, Death at an Early Age (Kozol, 1967).Kozol, J. (1967). Death at an early age: The destruction of the hearts and minds of negro children in the Boston public schools. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

Kozol (1991)Kozol, J. (1991). Savage inequalities: Children in America’s schools. New York, NY: Crown. later traveled around the United States and systematically compared public schools in several cities’ inner-city neighborhoods to those in the cities’ suburbs. Everywhere he went, he found great discrepancies in school spending and in the quality of instruction. In schools in Camden, New Jersey, for example, spending per pupil was less than half the amount spent in the nearby, much wealthier town of Princeton. Chicago and New York City schools spent only about half the amount that some of the schools in nearby suburbs spent.

These numbers were reflected in other differences Kozol found when he visited city and suburban schools. In East St. Louis, Illinois, where most of the residents are poor and almost all are African American, schools had to shut down once because of sewage backups. The high school’s science labs were thirty to fifty years out of date when Kozol visited them; the biology lab had no dissecting kits. A history teacher had 110 students but only twenty-six textbooks, some of which were missing their first one hundred pages. At one of the city’s junior high schools, many window frames lacked any glass, and the hallways were dark because light bulbs were missing or not working. Visitors could smell urinals one hundred feet from the bathroom.

Contrast these conditions with those Kozol observed in suburban schools. A high school in a Chicago suburb had seven gyms and an Olympic-sized swimming pool. Students there could take classes in seven foreign languages. A suburban New Jersey high school offered fourteen AP courses, fencing, golf, ice hockey, and lacrosse, and the school district there had ten music teachers and an extensive music program.

From his observations, Kozol concluded that the United States is shortchanging its children in poor rural and urban areas. As we saw in Chapter 2 "Poverty", poor children start out in life with many strikes against them. The schools they attend compound their problems and help ensure that the American ideal of equal opportunity for all remains just that—an ideal—rather than a reality. As Kozol (1991, p. 233)Kozol, J. (1991). Savage inequalities: Children in America’s schools. New York, NY: Crown. observed, “All our children ought to be allowed a stake in the enormous richness of America. Whether they were born to poor white Appalachians or to wealthy Texans, to poor black people in the Bronx or to rich people in Manhasset or Winnetka, they are all quite wonderful and innocent when they are small. We soil them needlessly.”

Although the book in which Kozol reported these conditions was published more than twenty years ago, ample evidence (including the news story about Baltimore’s schools that began this chapter) shows these conditions persist today. A recent news report discussed public schools in Washington, DC. More than 75 percent of the schools in the city had a leaking roof at the time the report was published, and 87 percent had electrical problems, some of which involved shocks or sparks. Most of the schools’ cafeterias—85 percent—had health violations, including peeling paint near food and rodent and roach infestation. Thousands of requests for building repairs, including 1,100 labeled “urgent” or “dangerous,” had been waiting more than a year to be addressed. More than one-third of the schools had a mouse infestation, and in one elementary school, there were so many mice that the students gave them names and drew their pictures. An official with the city’s school system said, “I don’t know if anybody knows the magnitude of problems at D.C. public schools. It’s mind-boggling” (Keating & Haynes, 2007).Keating, D., & Haynes, V. D. (2007, June 10). Can DC schools be fixed? The Washington Post, p. A1.

Large funding differences in the nation’s schools also endure. In Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, for example, annual per-pupil expenditure was $10,878 in 2010; in nearby suburban Lower Merion Township, it was $21,110, or 95 percent higher than Philadelphia’s expenditure (Federal Education Budget Project, 2012).Federal Education Budget Project. (2012). K–12: Pennsylvania. Retrieved January 2, 2012, from http://febp.newamerica.net/k12/PA.

Teacher salaries are related to these funding differences. Salaries in urban schools in low-income neighborhoods are markedly lower than those in schools in wealthier neighborhoods (Dillon, 2011).Dillon, S. (2011, December 1). Districts pay less in poor schools, report says. New York Times, p. A29. As a result, teachers at the low-income schools tend to be inexperienced teachers just out of college. All things equal, they are less likely than their counterparts at wealthier schools to be effective teachers.

Teaching Young Students about Science and Conservation

Since 1999, the Ocean Discovery Institute (ODI) has taught more than 40,000 public school students in a low-income San Diego neighborhood about the ocean and the environment. Most of the students are Latino, and a growing number are recent immigrants from Southeast Asia and East Africa. By learning about ocean science, the students also learn something about geology, physics, and other sciences. ODI’s program has grown over the years, and it now services more than 5,000 students annually in ten schools. To accomplish its mission, ODI engages in several kinds of activities.

First, ODI instructors teach hands-on marine science activities to students in grades 3–6. They also consult closely with the schools’ teachers about the science curriculum taught in the schools.

Second, ODI runs an after-school program in which they provide marine science–based lessons as well as academic, social, and college-entry support to approximately sixty students in grades 6–12.

Third, ODI takes about twenty high school students every summer to the Sea of Cortez in Baja California, Mexico, for an intensive five-week research experience at a field research station. Before they do so, they are trained for several weeks in laboratory and field research procedures, and they also learn how to swim and snorkel. After they arrive at the field research station, they divide into three research teams; each team works on a different project under the guidance of ODI instructors and university and government scientists. A recent project, which won an award from the World Wildlife Fund, has focused on reducing the number of sea turtles that are accidentally caught in fishing nets.

The instruction provided by ODI has changed the lives of many students. Perhaps most notably, about 80 percent of the students who have participated in the after-school or summer program have attended a four-year college or university (with almost all declaring a major in one of the sciences), compared to less than one-third of students in their schools who have not participated in these programs. One summer program student, whose parents were deported by the government, recalls the experience fondly: “I have learned to become independent, and I pushed myself to try new things. Now I know I can overcome barriers and take chances…I am prepared to overcome challenges and follow my dreams.”

In 2011, ODI was one of three organizations that received the Presidential Award for Excellence in Science, Mathematics, and Engineering Mentoring. Several ODI officials and students traveled to the White House to take part in various events and accept the award from President Obama. As this award attests, the Ocean Discovery Institute is making a striking difference in the lives of low-income San Diego students. For further information, visit http://www.oceandiscoveryinstitute.org. (Full disclosure: The author’s son works for ODI.)

Source: Ocean Discovery Institute, 2011Ocean Discovery Institute. (2011). Believe: A PEN in the classroom anthology. San Diego, CA: Author.

A related issue to school inequality is school racial segregation. Before 1954, schools in the South were racially segregated by law (de jure segregationSchool segregation stemming from legal requirements.). Communities and states had laws that dictated which schools white children attended and which schools African American children attended. Schools were either all white or all African American, and, inevitably, white schools were much better funded than African American schools. Then in 1954, the US Supreme Court outlawed de jure school segregation in its famous Brown v. Board of Education decision. Southern school districts fought this decision with legal machinations, and de jure school segregation did not really end in the South until the civil rights movement won its major victories a decade later.

Meanwhile, northern schools were also segregated; decades after the Brown decision, they have become even more segregated. School segregation in the North stemmed, both then and now, not from the law but from neighborhood residential patterns. Because children usually go to schools near their homes, if adjacent neighborhoods are all white or all African American, then the schools for these neighborhoods will also be all white or all African American, or mostly so. This type of segregation is called de facto segregationSchool segregation stemming from neighborhood residential patterns..

Today many children continue to go to schools that are segregated because of neighborhood residential patterns, a situation that Kozol (2005)Kozol, J. (2005). The shame of the nation: The restoration of apartheid schooling in America. New York, NY: Crown. calls “apartheid schooling.” About 40 percent of African American and Latino children attend schools that are very segregated (at least 90 percent of their students are of color); this level of segregation is higher than it was four decades ago. Although such segregation is legal, it still results in schools that are all African American and/or all Latino and that suffer severely from lack of funding, poor physical facilities, and poorly paid teachers (Orfield, Siegel-Hawley, & Kucsera, 2011).Orfield, G., Siegel-Hawley, G., & Kucsera, J. (2011). Divided we fail: Segregated and unequal schools in the Southland. Los Angeles, CA: Civil Rights Project.

During the 1960s and 1970s, states, municipalities, and federal courts tried to reduce de facto segregation by busing urban African American children to suburban white schools and, less often, by busing white suburban children to African American urban schools. Busing inflamed passions as perhaps few other issues did during those decades (Lukas, 1985).Lukas, J. A. (1985). Common ground: A turbulent decade in the lives of three American families. New York, NY: Knopf. White parents opposed it because they did not want their children bused to urban schools, where, they feared, the children would be unsafe and receive an inferior education. The racial prejudice that many white parents shared heightened their concerns over these issues. African American parents were more likely to see the need for busing, but they, too, wondered about its merits, especially because it was their children who were bused most often and faced racial hostility when they entered formerly all-white schools.

As one possible solution to reduce school segregation, some cities have established magnet schools, schools for high-achieving students of all races to which the students and their families apply for admission (Vopat, 2011).Vopat, M. C. (2011). Magnet schools, innate talent, and social justice. Theory and Research in Education, 9, 59–72. Although these schools do help some students whose families are poor and of color, their impact on school segregation has been minimal because the number of magnet schools is low and because they are open only to the very best students who, by definition, are also few in number. Some critics also say that magnet schools siphon needed resources from public school systems and that their reliance on standardized tests makes it difficult for African American and Latino students to gain admission.

Children who attend a public school ordinarily attend the school that is designated for the neighborhood in which they live, and they and their parents normally have little choice in the matter. One of the most popular but also controversial components of the school reform movement today is school choicePrograms in which parents and their children, primarily from low-income families in urban areas, receive public funds to attend a school different from their neighborhood’s school., in which parents and their children, primarily from low-income families in urban areas, receive public funds to attend a school different from their neighborhood’s school. School choice has two components. The first component involves education vouchers, which parents can use as tuition at private or parochial (religious) schools. The second component involves charter schoolsPublic schools built and operated by for-profit companies and to which students normally apply for admission., which are public schools (because public funds pay for students’ tuition) built and operated by for-profit companies. Students normally apply for admission to these schools; sometimes they are accepted based on their merit and potential, and sometimes they are accepted by lottery. Both components have strong advocates and fierce critics. We examine each component in turn.

Advocates of school choice programs involving education vouchers say they give low-income families an option for high-quality education they otherwise would be unable to afford. These programs, the advocates add, also help improve the public schools by forcing them to compete for students with their private and parochial counterparts. In order to keep a large number of parents from using vouchers to send their children to the latter schools, public schools have to upgrade their facilities, improve their instruction, and undertake other steps to make their brand of education an attractive alternative. In this way, school choice advocates argue, vouchers have a “competitive impact” that forces public schools to make themselves more attractive to prospective students (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2011).National Conference of State Legislatures. (2011). Publicly funded school voucher programs. Retrieved January 2, 2012, from http://www.ncsl.org/default.aspx?tabid=12942.

Critics of school choice programs say they harm the public schools by decreasing their enrollments and therefore their funding. Public schools do not have the money now to compete with private and parochial ones, nor will they have the money to compete with them if vouchers become more widespread. Critics also worry that voucher programs will lead to a “brain drain” of the most academically motivated children and families from low-income schools (Crone, 2011).Crone, J. A. (2011). How can we solve our social problems? (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press.

Because school choice programs and school voucher systems are still relatively new, scholars have not yet had time to assess whether they improve their students’ academic achievement. Some studies do find small improvements, but methodological problems make it difficult to reach any firm conclusions at this point (DeLuca & Dayton, 2009).DeLuca, S., & Dayton, E. (2009). Switching social contexts: The effects of housing mobility and school choice programs on youth outcomes. Annual Review of Sociology, 35(1), 457–491. Although there is also little research on the impact of school choice programs on funding and other aspects of public school systems, some evidence does indicate a negative impact. In Milwaukee, for example, enrollment decline from the use of vouchers cost the school system $26 million in state aid during the 1990s, forcing a rise in property taxes to replace the lost funds. Because the students who left the Milwaukee school system came from most of its 157 public schools, only a few left any one school, diluting the voucher system’s competitive impact. Thus although school choice programs may give some families alternatives to public schools, they might not have the competitive impact on public schools that their advocates claim, and they may cost public school systems state aid (Cooper, 1999).Cooper, K. J. (1999, June 25). Under vouchers, status quo rules. The Washington Post, p. A3.

About 5,000 charter schools operate across the nation, with about 3 percent of American children attending them. Charter schools and their proponents claim that students fare better in these schools than in conventional public schools because of the charter schools’ rigorous teaching methods, strong expectations for good behavior, small classrooms, and other advantages (National Alliance for Public Charter Schools, 2012).National Alliance for Public Charter Schools. (2012). Why charter schools? Retrieved January 11, 2012, from http://www.publiccharters.org/About-Charter-Schools/Why-Charter-Schools003F.aspx.

Critics say charter schools incur the same problems that education vouchers incur: They take some of the brightest students from a city’s conventional public schools and lead to lower funding for these schools (Ravitch, 2010; Rosenfeld, 2012).Ravitch, D. (2010, March 8). Why I changed my mnd about school reform. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748704869304575109443305343962.html; Rosenfeld, L. (2012, March 16). How charter schools can hurt. New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/17/opinion/how-charter-schools-can-hurt.html?emc=tnt&tntemail0=y. Critics also cite research findings that charter schools do not in fact deliver the strong academic performance claimed by their advocates. For example, a study that compared test scores at charter schools in sixteen states with those at public schools found that the charter schools did worse overall: 17 percent of charter schools had better scores than public schools, 46 percent had scores similar to those of public schools, and 37 percent had lower scores (Center for Research on Education Outcomes, 2009).Center for Research on Education Outcomes. (2009). Multiple choice: Charter school performance in 16 states. Stanford, CA: Author.

Even when charter school test scores are higher, there is the methodological problem that students are not randomly assigned to attend a charter school (Basile, 2010).Basile, M. (2010). False impression: How a widely cited study vastly overstates the benefits of charter schools. New York, NY: Century Foundation. It is thus possible that the students and parents who apply to charter schools are more highly motivated than those who do not. If so, the higher test scores found in some charter schools may reflect the motivation of the students attending these schools, and not necessarily the schools’ teaching methods. It is also true that charter schools do not usually enroll students who know little English (because their parents are immigrants) and students with disabilities or other problems. All such students often face difficulties in doing well in school. This is yet another possible reason that a small number of charter schools outperform public schools. Despite the popularity of charter schools, then, the academic case for them remains to be proven.

Before the late 1960s and early 1970s, many colleges and universities, including several highly selective campuses, were single-sex institutions. Since that time, almost all the male colleges and many of the female colleges have gone coed. A few women’s colleges still remain, as their administrators and alumnae say that women can achieve much more in a women’s college than in a coed institution. The issue of single-sex institutions has been more muted at the secondary school level, as most public schools have been coeducational since the advent of free, compulsory education during the nineteenth century. However, several private schools were single-sex ones from their outset, and many of these remain today. Still, the trend throughout the educational world was toward coeducation.

Since the 1990s, however, some education specialists have argued that single-sex secondary schools, or at least single-sex classes, might make sense for girls or for boys. In response, single-sex classes and single-sex schools have arisen in at least seventeen US cities. The argument for single-sex learning for girls rests on the same reasons advanced by advocates for women’s colleges: Girls can do better academically, and perhaps especially in math and science classes, when they are by themselves. The argument for boys rests on a different set of reasons (National Association for Single Sex Public Education, 2011).National Association for Single Sex Public Education. (2011). Advantages for boys. Retrieved January 2, 2012, from http://www.singlesexschools.org/advantages-forboys.htm. Boys in classes with girls are more likely to act “macho” and thus to engage in disruptive behavior; in single-sex classes, boys thus behave better and are more committed to their studies. They also feel freer to exhibit an interest in music, the arts, and other subjects not usually thought of as “macho” topics. Furthermore, because the best students in coed schools are often girls, many boys tend to devalue academic success in coed settings and are more likely to value it in single-sex settings. Finally, in a boys-only setting, teachers can use examples and certain teaching techniques that boys may find especially interesting, such as the use of snakes to teach biology. To the extent that single-sex education may benefit boys for any of these reasons, these benefits are often thought to be highest for boys from families living in poverty or near poverty.

What does the research evidence say about single-sex schooling’s benefits? A review of several dozen studies concluded that the results of single-sex schooling are mixed overall but that there are slightly more favorable outcomes for single-sex schools compared to coeducational schools (US Department of Education, 2005).US Department of Education. (2005). Single-sex versus secondary schooling: A systematic review. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Evaluation and Policy Development. However, the review noted that methodological problems limited the value of the studies it examined. For example, none of the studies involved random assignment of students to single-sex or coeducational schooling. Further, all the studies involved high school students and a majority involved students in Catholic schools. This limited scope prompted the call for additional studies of younger students and those in public schools.

Another review of the research evidence was more critical of single-sex schooling (Halpern et al., 2011).Halpern, D. F., Eliot, L., Bigler, R. S., Fabes, R. A., Hanish, L. D., Hyde, J., et al. (2011). The pseudoscience of single-sex schooling. Science, 333, 1706–1707. This review concluded that such schooling does not benefit girls or boys and in fact does them harm by reinforcing gender-role stereotypes. Boys in all-boy classes become more aggressive, the review said, and girls in all-girl classes become more feminine. The review also argued that single-sex schooling is based on a faulty, outdated understanding of how girls and boys learn and function. Drawing on this review and other evidence, two critics of single-sex education recently concluded, “So there is a veritable mountain of evidence, growing every day, that the single-sex classroom is not a magic bullet to save American education. And scant evidence that it heightens the academic achievement of girls and boys” (Barnett & Rivers, 2012).Barnett, R. C., & Rivers, C. (2012, February 17). Why science doesn’t support single-sex classes. Education Week. Retrieved from http://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2012/02/17/21barnett.h31.html?tkn=XNPFPP3DSaPBokSRePilYv9tz%2FsDy4SQ5jGa&cmp=ENL -EU-VIEWS1.

The Importance of Preschool and Summer Learning Programs for Low-Income Children

The first few years of life are absolutely critical for a child’s neurological and cognitive development. What happens, or doesn’t happen, before ages 5 and 6 can have lifelong consequences for a child’s educational attainment, adolescent behavior, and adult employment and family life. However, as this chapter and previous chapters emphasize, low-income children face many kinds of obstacles during this critical phase of their lives. Among other problems, their families are often filled with stressful life events that impair their physical and mental health and neurological development, and their parents read and talk to them much less on the average than wealthier parents do. These difficulties in turn lower their school performance and educational attainment, with negative repercussions continuing into adulthood.

To counteract these problems and enhance low-income children’s ability to do well in school, two types of programs have been repeatedly shown to be very helpful and even essential. The first is preschool, a general term for semiformal early learning programs that take place roughly between ages 3 and 5. As the name of the famous Head Start program implies, preschool is meant to help prepare low-income children for kindergarten and beyond. Depending on the program, preschool involves group instruction and play for children, developmental and health screening, and other components. Many European nations have high-quality preschool programs that are free or heavily subsidized, but these programs are, by comparison, much less prevalent in the United States and often more costly for parents.

Preschool in the United States has been shown to have positive benefits that extend well into adulthood. For example, children who participate in Head Start and certain other programs are more likely years later to graduate high school and attend college. They also tend to have higher salaries in their twenties, and they are less likely to engage in delinquency and crime.

The second program involves summer learning. Educators have discovered that summer is an important time for children’s learning. During the summer, children from middle-class and wealthier families tend to read books, attend summer camp and/or engage in other group activities, and travel with their parents. When they return to school in September, their reading and math skills are higher than when the summer began. In contrast, low-income children are much less likely to have these types of summer experiences, and those who benefitted from school lunch programs during the academic year often go hungry. As a result, their reading and math skills are lower when they return to school than when the summer began.

In response to this discovery, many summer learning programs have been established. They generally last from four to eight weeks and are held at schools, campgrounds, community centers, or other locations. Although these programs are still relatively new and not yet thoroughly studied, a recent review concluded that they “can be effective and are likely to have positive impacts when they engage students in learning activities that are hands-on, enjoyable, and have real-world applications.”

Preschool programs help children in the short and long term, and summer programs appear to have the same potential. Their expansion in the United States would benefit many aspects of American society. Because their economic benefits outweigh their economic costs, they are a “no-brainer” for comprehensive social reform efforts.

Sources: Child Trends, 2011; Downey & Gibbs, 2012; Garces, Thomas, & Currie, 2003; Reynolds, Temple, Ou, Arteaga, & White, 2011; Terzian & Moore, 2009Child Trends. (2011). Research-based responses to key questions about the 2010 Head Start impact study. Washington, DC: Author; Downey, D. B., & Gibbs, B. G. (2012). How schools really matter. In D. Hartmann & C. Uggen (Eds.), The Contexts Reader (2nd ed., pp. 80–86). New York, NY: W. W. Norton; Garces, E., Thomas, D., & Currie, J. (2003). Longer-term effects of Head Start. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; Reynolds, A. J., Temple, J. A., Ou, S.-R., Arteaga, I. A., & White, B. A. B. (2011, July 15). School-based early childhood education and age-28 well-being: Effects by timing, dosage, and subgroups. Science, 360–364; Terzian, M., & Moore, K. A. (2009). What works for summer learning programs for low-income children and youth: Preliminary lessons from experimental evaluations of social interventions. Washington, DC: Child Trends.

The issue of school violence won major headlines during the 1990s, when many children, teachers, and other individuals died in the nation’s schools. From 1992 until 1999, 248 students, teachers, and other people died from violent acts (including suicide) on school property, during travel to and from school, or at a school-related event, for an average of about thirty-five violent deaths per year (Zuckoff, 1999).Zuckoff, M. (1999, May 21). Fear is spread around nation. The Boston Globe, p. A1.

Several of these deaths occurred in mass shootings. In just a few examples, in December 1997, a student in a Kentucky high school shot and killed three students in a before-school prayer group. In March 1998, two middle school students in Arkansas pulled a fire alarm to evacuate their school and then shot and killed four students and one teacher as they emerged. Two months later, an Oregon high school student killed his parents and then went to his school cafeteria, where he killed two students and wounded twenty-two others. Against this backdrop, the infamous April 1999 school shootings at Columbine High School in Littleton, Colorado, where two students murdered twelve other students and one teacher before killing themselves, seemed like the last straw. Within days, school after school across the nation installed metal detectors, located police at building entrances and in hallways, and began questioning or suspending students joking about committing violence. People everywhere wondered why the schools were becoming so violent and what could be done about it. A newspaper headline summarized their concern: “fear is spread around nation” (Zuckoff, 1999).Zuckoff, M. (1999, May 21). Fear is spread around nation. The Boston Globe, p. A1.

Fortunately, school violence has declined since the 1990s, with fewer students and other people dying in the nation’s schools or being physically attacked. As this trend indicates, the risk of school violence should not be exaggerated: Statistically speaking, schools are very safe, especially in regard to fatal violence. Two kinds of statistics illustrate this point. First, less than 1 percent of all homicides involving school-aged children take place in or near school; virtually all children’s homicides occur in or near a child’s home. Second, an average of seventeen students are killed at school yearly; because about 56 million students attend US elementary and secondary schools, the chances are less than one in 3 million that a student will be killed at school. The annual rate of other serious school violence (rape and sexual assault, aggravated assault, and robbery) is only three crimes per one hundred students; although this is still three too many, it does indicate that 97 percent of students do not suffer these crimes (National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, 2010).National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. (2010). Understanding school violence fact sheet. Washington, DC: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, depicted here, killed thirteen people at Columbine High School in 1999 before killing themselves. Their massacre led people across the nation to question why violence was occurring in the schools and to wonder what could be done to reduce it.

Image courtesy of Columbine High School, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Eric_harris_dylan_klebold.jpg.

Bullying is another problem in the nation’s elementary and secondary schools and is often considered a specific type of school violence. However, bullying can take many forms, such as taunting, that do not involve the use or threat of physical violence. As such, we consider bullying here as a separate problem while acknowledging its close relation to school violence.