“America’s First Muslim College to Open This Fall,” the headline said. The United States has hundreds of colleges and universities run by or affiliated with the Catholic Church and several Protestant and Jewish denominations, and now it was about to have its first Muslim college. Zaytuna College in Berkeley, California, had just sent out acceptance letters to students who would make up its inaugural class in the fall of 2010. The school’s founder said it would be a Muslim liberal arts college whose first degrees would be in Islamic law and theology and in the Arabic language. The chair of the college’s academic affairs committee explained, “We are trying to graduate well-rounded students who will be skilled in a liberal arts education with the ability to engage in a wider framework of society and the variety of issues that confront them.…We are thinking of how to set up students for success. We don’t see any contradiction between religious and secular subjects.”

The college planned to rent a building in Berkeley during its first several years and was doing fund-raising to pay for the eventual construction or purchase of its own campus. It hoped to obtain academic accreditation within a decade. Because the United States has approximately 6 million Muslims whose numbers have tripled since the 1970s, college officials were optimistic that their new institution would succeed. An official with the Islamic Society of North America, which aids Muslim communities and organizations and provides chaplains for the U.S. military, applauded the new college. “It tells me that Muslims are coming of age,” he said. “This is one more thing that makes Muslims part of the mainstream of America. It is an important part of the development of our community.” (Oguntoyinbo, 2010)Oguntoyinbo, L. (2010, May 20). America’s first Muslim college to open this fall. Diverse: Issues in Higher Education. Retrieved from http://diverseeducation.com/article/13814/america-s-first-muslim-college-to-open-this-fall.html

The opening of any college is normally cause for celebration, but the news about this particular college aroused a mixed reaction. Some people wrote positive comments on the Web page on which this news article appeared, but two anonymous writers left very negative comments. One asked, “What if they teach radical Islam?” while the second commented, “Dose [sic] anyone know how Rome fell all those years ago? We are heading down the same road.”

As the reaction to this news story reminds us, religion and especially Islam have certainly been hot topics since 9/11, as America continues to worry about terrorist threats from people with Middle Eastern backgrounds. Many political and religious leaders urge Americans to practice religious tolerance, and advocacy groups have established programs and secondary school curricula to educate the public and students, respectively. Colleges and universities have responded with courses and workshops on Islamic culture, literature, and language. The controversy over Islam is just one example of the strong passions that religion and religious differences often arouse, in part because religion involves our dearest values.

This chapter presents a sociological understanding of religion. We begin by examining religion as a social institution and by sketching its history and practice throughout the world today. We then turn to the several types of religious organizations before concluding with a discussion of various aspects of religion in the United States.

Religion clearly plays an important role in American life. Most Americans believe in a deity, three-fourths pray at least weekly, and more than half attend religious services at least monthly. We tend to think of religion in individual terms because religious beliefs and values are highly personal for many people. However, religion is also a social institution, as it involves patterns of beliefs and behavior that help a society meet its basic needs, to recall the definition of social institution in Chapter 5 "Social Structure and Social Interaction". More specifically, religionThe set of beliefs and practices regarding sacred things that help a society understand the meaning and purpose of life. is the set of beliefs and practices regarding sacred things that help a society understand the meaning and purpose of life.

Because it is such an important social institution, religion has long been a key sociological topic. Émile Durkheim (1915/1947)Durkheim, É. (1947). The elementary forms of religious life (J. Swain, Trans.). Glencoe, IL: Free Press. (Original work published 1915) observed long ago that every society has beliefs about things that are supernatural and awe-inspiring and beliefs about things that are more practical and down-to-earth. He called the former beliefs sacredAspects of life that are supernatural and awe-inspiring. beliefs and the latter beliefs profaneAspects of life that are practical and down-to-earth. beliefs. Religious beliefs and practices involve the sacred: they involve things our senses cannot readily observe, and they involve things that inspire in us awe, reverence, and even fear.

Durkheim did not try to prove or disprove religious beliefs. Religion, he acknowledged, is a matter of faith, and faith is not provable or disprovable through scientific inquiry. Rather, Durkheim tried to understand the role played by religion in social life and the impact on religion of social structure and social change. In short, he treated religion as a social institution.

Sociologists since his time have treated religion in the same way. Anthropologists, historians, and other scholars have also studied religion. Historical work on religion reminds us of the importance of religion since the earliest societies, while comparative work on contemporary religion reminds us of its importance throughout the world today. Accordingly, Chapter 17 "Religion", Section 17.2 "Religion in Historical and Cross-Cultural Perspective" examines key aspects of the history of religion and its practice across the globe.

Every known society has practiced religion, although the nature of religious belief and practice has differed from one society to the next. Prehistoric people turned to religion to help them understand birth, death, and natural events such as hurricanes. They also relied on religion for help in dealing with their daily needs for existence: good weather, a good crop, an abundance of animals to hunt (Noss & Grangaard, 2008).Noss, D. S., & Grangaard, B. R. (2008). A history of the world’s religions (12th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Although the world’s most popular religions today are monotheisticBelieving in one god. (believing in one god), many societies in ancient times, most notably Egypt, Greece, and Rome, were polytheisticBelieving in more than one god. (believing in more than one god). You have been familiar with their names since childhood: Aphrodite, Apollo, Athena, Mars, Zeus, and many others. Each god “specialized” in one area; Aphrodite, for example, was the Greek goddess of love, while Mars was the Roman god of war (Noss & Grangaard, 2008).Noss, D. S., & Grangaard, B. R. (2008). A history of the world’s religions (12th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

During the Middle Ages, the Catholic Church dominated European life. The Church’s control began to weaken with the Protestant Reformation, which began in 1517 when Martin Luther, a German monk, spoke out against Church practices. By the end of the century, Protestantism had taken hold in much of Europe. Another founder of sociology, Max Weber, argued a century ago that the rise of Protestantism in turn led to the rise of capitalism. In his great book The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, Weber wrote that Protestant belief in the need for hard work and economic success as a sign of eternal salvation helped lead to the rise of capitalism and the Industrial Revolution (Weber, 1904/1958).Weber, M. (1958). The Protestant ethic and the spirit of capitalism (T. Parsons, Trans.). New York, NY: Scribner. (Original work published 1904) Although some scholars challenge Weber’s views for several reasons, including the fact that capitalism also developed among non-Protestants, his analysis remains a compelling treatment of the relationship between religion and society.

Moving from Europe to the United States, historians have documented the importance of religion since the colonial period. Many colonists came to the new land to escape religious persecution in their home countries. The colonists were generally very religious, and their beliefs guided their daily lives and, in many cases, the operation of their governments and other institutions. In essence, government and religion were virtually the same entity in many locations, and church and state were not separate. Church officials performed many of the duties that the government performs today, and the church was not only a place of worship but also a community center in most of the colonies (Gaustad & Schmidt, 2004).Gaustad, E. S., & Schmidt, L. E. (2004). The religious history of America. San Francisco, CA: HarperSanFrancisco. The Puritans of what came to be Massachusetts refused to accept religious beliefs and practices different from their own and persecuted people with different religious views. They expelled Anne Hutchinson in 1637 for disagreeing with the beliefs of the Puritans’ Congregational Church and hanged Mary Dyer in 1660 for practicing her Quaker faith.

Today the world’s largest religion is Christianity, to which more than 2 billion people, or about one-third the world’s population, subscribe. Christianity began 2,000 years ago in Palestine under the charismatic influence of Jesus of Nazareth and today is a Western religion, as most Christians live in the Americas and in Europe. Beginning as a cult, Christianity spread through the Mediterranean and later through Europe before becoming the official religion of the Roman Empire. Today, dozens of Christian denominations exist in the United States and other nations. Their views differ in many respects, but generally they all regard Jesus as the son of God, and many believe that salvation awaits them if they follow his example (Young, 2010).Young, W. A. (2010). The world’s religions: Worldviews and contemporary issues (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

The second largest religion is Islam, which includes about 1.6 billion Muslims, most of them in the Middle East, northern Africa, and parts of Asia. Muhammad founded Islam in the 600s A.D. and is regarded today as a prophet who was a descendant of Abraham. Whereas the sacred book of Christianity and Judaism is the Bible, the sacred book of Islam is the Koran. The Five Pillars of Islam guide Muslim life: (a) the acceptance of Allah as God and Muhammad as his messenger; (b) ritual worship, including daily prayers facing Mecca, the birthplace of Muhammad; (c) observing Ramadan, a month of prayer and fasting; (d) giving alms to the poor; and (e) making a holy pilgrimage to Mecca at least once before one dies.

The third largest religion is Hinduism, which includes more than 800 million people, most of whom live in India and Pakistan. Hinduism began about 2000 B.C. and, unlike Christianity, Judaism, and Islam, has no historic linkage to any one person and no real belief in one omnipotent deity. Hindus live instead according to a set of religious precepts called dharma. For these reasons Hinduism is often called an ethical religion. Hindus believe in reincarnation, and their religious belief in general is closely related to India’s caste system (see Chapter 9 "Global Stratification"), as an important aspect of Hindu belief is that one should live according to the rules of one’s caste.

Buddhism is another key religion and claims almost 400 million followers, most of whom live in Asia. Buddhism developed out of Hinduism and was founded by Siddhartha Gautama more than 500 years before the birth of Jesus. Siddhartha is said to have given up a comfortable upper-caste Hindu existence for one of wandering and poverty. He eventually achieved enlightenment and acquired the name of Buddha, or “enlightened one.” His teachings are now called the dhamma, and over the centuries they have influenced Buddhists to lead a moral life. Like Hindus, Buddhists generally believe in reincarnation, and they also believe that people experience suffering unless they give up material concerns and follow other Buddhist principles.

Another key religion is Judaism, which claims more than 13 million adherents throughout the world, most of them in Israel and the United States. Judaism began about 4,000 years ago when, according to tradition, Abraham was chosen by God to become the progenitor of his “chosen people,” first called Hebrews or Israelites and now called Jews. The Jewish people have been persecuted throughout their history, with anti-Semitism having its ugliest manifestation during the Holocaust of the 1940s, when 6 million Jews died at the hands of the Nazis. One of the first monotheistic religions, Judaism relies heavily on the Torah, which is the first five books of the Bible, and the Talmud and the Mishnah, both collections of religious laws and ancient rabbinical interpretations of these laws. The three main Jewish dominations are the Orthodox, Conservative, and Reform branches, listed in order from the most traditional to the least traditional. Orthodox Jews take the Bible very literally and closely follow the teachings and rules of the Torah, Talmud, and Mishnah, while Reform Jews think the Bible is mainly a historical document and do not follow many traditional Jewish practices. Conservative Jews fall in between these two branches.

A final key religion in the world today is Confucianism, which reigned in China for centuries but was officially abolished in 1949 after the Chinese Revolution ended in Communist control. People who practice Confucianism in China today do so secretly, and its number of adherents is estimated at some 5 or 6 million. Confucianism was founded by K’ung Fu-tzu, from whom it gets its name, about 500 years before the birth of Jesus. His teachings, which were compiled in a book called the Analects, were essentially a code of moral conduct involving self-discipline, respect for authority and tradition, and the kind treatment of everyone. Despite the official abolition of Confucianism, its principles continue to be important for Chinese family and cultural life.

As this overview indicates, religion takes many forms in different societies. No matter what shape it takes, however, religion has important consequences. These consequences can be both good and bad for the society and the individuals in it. Sociological perspectives expand on these consequences, and we now turn to them.

Sociological perspectives on religion aim to understand the functions religion serves, the inequality and other problems it can reinforce and perpetuate, and the role it plays in our daily lives (Emerson, Monahan, & Mirola, 2011).Emerson, M. O., Monahan, S. C., & Mirola, W. A. (2011). Religion matters: What sociology teaches us about religion in our world. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Table 17.1 "Theory Snapshot" summarizes what these perspectives say.

Table 17.1 Theory Snapshot

| Theoretical perspective | Major assumptions |

|---|---|

| Functionalism | Religion serves several functions for society. These include (a) giving meaning and purpose to life, (b) reinforcing social unity and stability, (c) serving as an agent of social control of behavior, (d) promoting physical and psychological well-being, and (e) motivating people to work for positive social change. |

| Conflict theory | Religion reinforces and promotes social inequality and social conflict. It helps convince the poor to accept their lot in life, and it leads to hostility and violence motivated by religious differences. |

| Symbolic interactionism | This perspective focuses on the ways in which individuals interpret their religious experiences. It emphasizes that beliefs and practices are not sacred unless people regard them as such. Once they are regarded as sacred, they take on special significance and give meaning to people’s lives. |

Much of the work of Émile Durkheim stressed the functions that religion serves for society regardless of how it is practiced or of what specific religious beliefs a society favors. Durkheim’s insights continue to influence sociological thinking today on the functions of religion.

First, religion gives meaning and purpose to life. Many things in life are difficult to understand. That was certainly true, as we have seen, in prehistoric times, but even in today’s highly scientific age, much of life and death remains a mystery, and religious faith and belief help many people make sense of the things science cannot tell us.

Second, religion reinforces social unity and stability. This was one of Durkheim’s most important insights. Religion strengthens social stability in at least two ways. First, it gives people a common set of beliefs and thus is an important agent of socialization (see Chapter 4 "Socialization"). Second, the communal practice of religion, as in houses of worship, brings people together physically, facilitates their communication and other social interaction, and thus strengthens their social bonds.

A third function of religion is related to the one just discussed. Religion is an agent of social control and thus strengthens social order. Religion teaches people moral behavior and thus helps them learn how to be good members of society. In the Judeo-Christian tradition, the Ten Commandments are perhaps the most famous set of rules for moral behavior.

A fourth function of religion is greater psychological and physical well-being. Religious faith and practice can enhance psychological well-being by being a source of comfort to people in times of distress and by enhancing their social interaction with others in places of worship. Many studies find that people of all ages, not just the elderly, are happier and more satisfied with their lives if they are religious. Religiosity also apparently promotes better physical health, and some studies even find that religious people tend to live longer than those who are not religious (Moberg, 2008).Moberg, D. O. (2008). Spirituality and aging: Research and implications. Journal of Religion, Spirituality & Aging, 20, 95–134. We return to this function later.

A final function of religion is that it may motivate people to work for positive social change. Religion played a central role in the development of the Southern civil rights movement a few decades ago. Religious beliefs motivated Martin Luther King Jr. and other civil rights activists to risk their lives to desegregate the South. Black churches in the South also served as settings in which the civil rights movement held meetings, recruited new members, and raised money (Morris, 1984).Morris, A. (1984). The origins of the civil rights movement: Black communities organizing for change. New York, NY: Free Press.

Religion has all of these benefits, but, according to conflict theory, it can also reinforce and promote social inequality and social conflict. This view is partly inspired by the work of Karl Marx, who said that religion was the “opiate of the masses” (Marx, 1964).Marx, K. (1964). Karl Marx: Selected writings in sociology and social philosophy (T. B. Bottomore, Trans.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. By this he meant that religion, like a drug, makes people happy with their existing conditions. Marx repeatedly stressed that workers needed to rise up and overthrow the bourgeoisie. To do so, he said, they needed first to recognize that their poverty stemmed from their oppression by the bourgeoisie. But people who are religious, he said, tend to view their poverty in religious terms. They think it is God’s will that they are poor, either because he is testing their faith in him or because they have violated his rules. Many people believe that if they endure their suffering, they will be rewarded in the afterlife. Their religious views lead them not to blame the capitalist class for their poverty and thus not to revolt. For these reasons, said Marx, religion leads the poor to accept their fate and helps maintain the existing system of social inequality.

As Chapter 11 "Gender and Gender Inequality" discussed, religion also promotes gender inequality by presenting negative stereotypes about women and by reinforcing traditional views about their subordination to men (Klassen, 2009).Klassen, P. (Ed.). (2009). Women and religion. New York, NY: Routledge. A declaration a decade ago by the Southern Baptist Convention that a wife should “submit herself graciously” to her husband’s leadership reflected traditional religious belief (Gundy-Volf, 1998).Gundy-Volf, J. (1998, September–October). Neither biblical nor just: Southern Baptists and the subordination of women. Sojourners, 12–13.

As the Puritans’ persecution of non-Puritans illustrates, religion can also promote social conflict, and the history of the world shows that individual people and whole communities and nations are quite ready to persecute, kill, and go to war over religious differences. We see this today and in the recent past in central Europe, the Middle East, and Northern Ireland. Jews and other religious groups have been persecuted and killed since ancient times. Religion can be the source of social unity and cohesion, but over the centuries it also has led to persecution, torture, and wanton bloodshed.

News reports going back since the 1990s indicate a final problem that religion can cause, and that is sexual abuse, at least in the Catholic Church. As you undoubtedly have heard, an unknown number of children were sexually abused by Catholic priests and deacons in the United States, Canada, and many other nations going back at least to the 1960s. There is much evidence that the Church hierarchy did little or nothing to stop the abuse or to sanction the offenders who were committing it, and that they did not report it to law enforcement agencies. Various divisions of the Church have paid tens of millions of dollars to settle lawsuits. The numbers of priests, deacons, and children involved will almost certainly never be known, but it is estimated that at least 4,400 priests and deacons in the United States, or about 4% of all such officials, have been accused of sexual abuse, although fewer than 2,000 had the allegations against them proven (Terry & Smith, 2006).Terry, K., & Smith, M. L. (2006). The nature and scope of sexual abuse of minors by Catholic priests and deacons in the United States: Supplementary data analysis. Washington, DC: United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. Given these estimates, the number of children who were abused probably runs into the thousands.

While functional and conflict theories look at the macro aspects of religion and society, symbolic interactionism looks at the micro aspects. It examines the role that religion plays in our daily lives and the ways in which we interpret religious experiences. For example, it emphasizes that beliefs and practices are not sacred unless people regard them as such. Once we regard them as sacred, they take on special significance and give meaning to our lives. Symbolic interactionists study the ways in which people practice their faith and interact in houses of worship and other religious settings, and they study how and why religious faith and practice have positive consequences for individual psychological and physical well-being.

Religious symbols indicate the value of the symbolic interactionist approach. A crescent moon and a star are just two shapes in the sky, but together they constitute the international symbol of Islam. A cross is merely two lines or bars in the shape of a “t,” but to tens of millions of Christians it is a symbol with deeply religious significance. A Star of David consists of two superimposed triangles in the shape of a six-pointed star, but to Jews around the world it is a sign of their religious faith and a reminder of their history of persecution.

Religious rituals and ceremonies also illustrate the symbolic interactionist approach. They can be deeply intense and can involve crying, laughing, screaming, trancelike conditions, a feeling of oneness with those around you, and other emotional and psychological states. For many people they can be transformative experiences, while for others they are not transformative but are deeply moving nonetheless.

Many types of religious organizations exist in modern societies. Sociologists usually group them according to their size and influence. Categorized this way, three types of religious organizations exist: church, sect, and cult (Emerson, Monahan, & Mirola, 2011).Emerson, M. O., Monahan, S. C., & Mirola, W. A. (2011). Religion matters: What sociology teaches us about religion in our world. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. A church further has two subtypes: the ecclesia and denomination. We first discuss the largest and most influential of the types of religious organization, the ecclesia, and work our way down to the smallest and least influential, the cult.

A churchA large, bureaucratically organized religious organization that’s closely integrated into the larger society. is a large, bureaucratically organized religious organization that is closely integrated into the larger society. Two types of church organizations exist. The first is the ecclesiaA large, bureaucratically organized religious organization that is a formal part of the state and has most or all of a state’s citizens as its members., a large, bureaucratic religious organization that is a formal part of the state and has most or all of a state’s citizens as its members. As such, the ecclesia is the national or state religion. People ordinarily do not join an ecclesia; instead they automatically become members when they are born. A few ecclesiae exist in the world today, including Islam in Saudi Arabia and some other Middle Eastern nations, the Catholic Church in Spain, the Lutheran Church in Sweden, and the Anglican Church in England.

As should be clear, in an ecclesiastic society there may be little separation of church and state, because the ecclesia and the state are so intertwined. In some ecclesiastic societies, such as those in the Middle East, religious leaders rule the state or have much influence over it, while in others, such as Sweden and England, they have little or no influence. In general the close ties that ecclesiae have to the state help ensure they will support state policies and practices. For this reason, ecclesiae often help the state solidify its control over the populace.

The second type of church organization is the denominationA large, bureaucratically organized religious organization that is closely integrated into the larger society but is not a formal part of the state., a large, bureaucratic religious organization that is closely integrated into the larger society but is not a formal part of the state. In modern pluralistic nations, several denominations coexist. Most people are members of a specific denomination because their parents were members. They are born into a denomination and generally consider themselves members of it the rest of their lives, whether or not they actively practice their faith, unless they convert to another denomination or abandon religion altogether.

A relatively recent development in religious organizations is the rise of the so-called megachurch, a church at which more than 2,000 people worship every weekend on the average. Several dozen have at least 10,000 worshippers (Priest, Wilson, & Johnson, 2010; Warf & Winsberg, 2010);Priest, R. J., Wilson, D., & Johnson, A. (2010). U.S. megachurches and new patterns of global mission. International Bulletin of Missionary Research, 34(2), 97–104; Warf, B., & Winsberg, M. (2010). Geographies of megachurches in the United States. Journal of Cultural Geography, 27(1), 33–51. the largest U.S. megachurch, in Houston, has more than 35,000 worshippers and is nicknamed a “gigachurch.” There are more than 1,300 megachurches in the United States, a steep increase from the 50 that existed in 1970, and their total membership exceeds 4 million. About half of today’s megachurches are in the South, and only 5% are in the Northeast. About one-third are nondenominational, and one-fifth are Southern Baptist, with the remainder primarily of other Protestant denominations. A third spend more than 10% of their budget on ministry in other nations. Some have a strong television presence, with Americans in the local area or sometimes around the country watching services and/or preaching by televangelists and providing financial contributions in response to information presented on the television screen.

Compared to traditional, smaller churches, megachurches are more concerned with meeting their members’ practical needs in addition to helping them achieve religious fulfillment. Some even conduct market surveys to determine these needs and how best to address them. As might be expected, their buildings are huge by any standard, and they often feature bookstores, food courts, and sports and recreation facilities. They also provide day care, psychological counseling, and youth outreach programs. Their services often feature electronic music and light shows.

Although megachurches are popular, they have been criticized for being so big that members are unable to develop the close bonds with each other and with members of the clergy characteristic of smaller houses of worship. Their supporters say that megachurches involve many people in religion who would otherwise not be involved.

A sectA relatively small religious organization that is not closely integrated into the larger society and that often conflicts with at least some of its norms and values. is a relatively small religious organization that is not closely integrated into the larger society and that often conflicts with at least some of its norms and values. Typically a sect has broken away from a larger denomination in an effort to restore what members of the sect regard as the original views of the denomination. Because sects are relatively small, they usually lack the bureaucracy of denominations and ecclesiae and often also lack clergy who have received official training. Their worship services can be intensely emotional experiences, often more so than those typical of many denominations, where worship tends to be more formal and restrained. Members of many sects typically proselytize and try to recruit new members into the sect. If a sect succeeds in attracting many new members, it gradually grows, becomes more bureaucratic, and, ironically, eventually evolves into a denomination. Many of today’s Protestant denominations began as sects, as did the Mennonites, Quakers, and other groups. The Amish in the United States are perhaps the most well-known example of a current sect.

A cultA small religious organization that is at great odds with the norms and values of the larger society. is a small religious organization that is at great odds with the norms and values of the larger society. Cults are similar to sects but differ in at least three respects. First, they generally have not broken away from a larger denomination and instead originate outside the mainstream religious tradition. Second, they are often secretive and do not proselytize as much. Third, they are at least somewhat more likely than sects to rely on charismatic leadership based on the extraordinary personal qualities of the cult’s leader.

Although the term cult today raises negative images of crazy, violent, small groups of people, it is important to keep in mind that major world religions, including Christianity, Islam, and Judaism, and denominations such as the Mormons all began as cults. Research challenges several popular beliefs about cults, including the ideas that they brainwash people into joining them and that their members are mentally ill. In a study of the Unification Church (Moonies), Eileen Barker (1984)Barker, E. (1984). The making of a Moonie: Choice or brainwashing. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. found no more signs of mental illness among people who joined the Moonies than in those who did not. She also found no evidence that people who joined the Moonies had been brainwashed into doing so.

Another image of cults is that they are violent. In fact, most are not violent. However, some cults have committed violence in the recent past. In 1995 the Aum Shinrikyo (Supreme Truth) cult in Japan killed 10 people and injured thousands more when it released bombs of deadly nerve gas in several Tokyo subway lines (Strasser & Post, 1995).Strasser, S., & Post, T. (1995, April 3). A cloud of terror—and suspicion. Newsweek 36–41. Two years earlier, the Branch Davidian cult engaged in an armed standoff with federal agents in Waco, Texas. When the agents attacked its compound, a fire broke out and killed 80 members of the cult, including 19 children; the origin of the fire remains unknown (Tabor & Gallagher, 1995).Tabor, J. D., & Gallagher, E. V. (1995). Why Waco? Cults and the battle for religious freedom in America. Berkeley: University of California Press. A few cults have also committed mass suicide. In another example from the 1990s, more than three dozen members of the Heaven’s Gate cult killed themselves in California in March 1997 in an effort to communicate with aliens from outer space (Hoffman & Burke, 1997).Hoffman, B., & Burke, K. (1997). Heaven’s Gate: Cult suicide in San Diego. New York, NY: Harper Paperbacks. Some two decades earlier, more than 900 members of the People’s Temple cult killed themselves in Guyana under orders from the cult’s leader, Jim Jones (Stoen, 1997).Stoen, T. (1997, April 7). The most horrible night of my life. Newsweek 44–45.

The United States is generally regarded as a fairly religious nation. In a 2009 survey administered by the Gallup Organization to 114 nations, 65% of Americans answered yes when asked, “Is religion an important part of your daily life?” (Crabtree, 2010).Crabtree, S. (2010). Religiosity highest in world’s poorest nations. Retrieved from http://www.gallup.com/poll/142727/religiosity-highest-world-poorest-nations.aspx In a 2007 Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life survey, about 83% of Americans expressed a religious preference, 61% were official members of a local house of worship, and 39% attended religious services at least weekly (Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life, 2008).Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life. (2008). U.S. religious landscape survey. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. These figures show that religion plays a significant role in the lives of many Americans.

Moreover, Americans seem more religious than the citizens of almost all the other democratic, industrialized nations with which the United States is commonly compared. Evidence for this conclusion comes from the 2009 Gallup survey mentioned in the preceding paragraph. Whereas 65% of Americans said religion was an important part of their daily lives, comparable percentages from other democratic, industrialized nations included the following: Spain, 49%; Canada, 42%; France, 30%; United Kingdom, 27%; and Sweden, 17% (Crabtree, 2010).Crabtree, S. (2010). Religiosity highest in world’s poorest nations. Retrieved from http://www.gallup.com/poll/142727/religiosity-highest-world-poorest-nations.aspx Among its peer nations, then, the United States stands out for being religious.

When we consider all the nations of the world, however, the U.S. ranking is much lower. In more than half the nations surveyed by Gallup in 2009, at least 84% of respondents said religion was an important part of their daily lives. The U.S. rate of 65% ranked 85th out of the 114 nations in this survey (Crabtree, 2010).Crabtree, S. (2010). Religiosity highest in world’s poorest nations. Retrieved from http://www.gallup.com/poll/142727/religiosity-highest-world-poorest-nations.aspx However, because the United States ranks higher than most of the democratic, industrialized nations with which it is most aptly compared, it makes sense to regard the United States as fairly religious. The “Learning From Other Societies” box discusses what else can be learned from the international comparisons in the Gallup survey.

Poverty and the Importance of Religion

The 2009 Gallup international survey on religion discussed in the text revealed an interesting pattern that is relevant for understanding religious differences among the 50 states of the United States.

Of the 114 nations included in the Gallup survey, people in the poorest nations were most likely to say that religion was an important part of their daily lives, and people in the richest nations were least likely to feel this way. The 10 most religious nations according to this measure, with at least 98% of their populations saying that religion was an important part of their daily lives, all had a per-capita gross domestic product (GDP) below $5,000: Bangladesh, Niger, Yemen, Indonesia, Malawi, Sri Lanka, Somaliland region, Djibouti, Mauritania, and Burundi. In contrast, among the 10 least religious nations, with 30% or fewer saying religion was important, were some of the world’s wealthiest nations: Sweden, Denmark, Japan, Hong Kong, the United Kingdom, and France. In the world’s poorest nations, those whose per-capita GDP is below $2,000, the median proportion whose citizens are religious according to the Gallup measure was 95%; in the richest nations, those whose per-capita GDP is above $25,000, the same median proportion was only 47%.

A Gallup report concluded that these results demonstrate “the strong relationship between a country’s socioeconomic status and the religiosity of its residents” (Crabtree, 2010).Crabtree, S. (2010). Religiosity highest in world’s poorest nations. Retrieved from http://www.gallup.com/poll/142727/religiosity-highest-world-poorest-nations.aspx Drawing on research by sociologists and other social scientists, the report explained that religion helps people in poorer nations cope with the many hardships that poverty creates.

Gallup’s international findings and explanation for the poverty-religiosity relationship pattern they exhibited helps explain differences among the 50 states in the United States. In 2008, Gallup conducted surveys in each state in which respondents were asked whether religion was an important part of their daily lives. The 11 highest ranking states, with at least 74% of their populations saying that religion was an important part of their daily lives, were all Southern states. Mississippi ranked highest at 85%.

There are many reasons for the high degree of Southern religiosity, and a Gallup report noted that the states differ in their religious traditions, denominations, and racial and ethnic compositions (Newport, 2009).Newport, F. (2009). State of the states: Importance of religion. Retrieved from http://www.gallup.com/poll/114022/state-states-importance-religion.aspx Although these and other factors might help explain Southern religiosity, it is notable that the Southern states are also generally the poorest in the nation. If the poorest nations of the world are more religious in part because of their poverty, then the Southern states may also be more religious partly because of their poverty. In understanding religious differences among the different regions of the country, the United States has much to learn from the other nations of the world.

Religious affiliationActual membership in a church or synagogue, or just a stated identification with a particular religion whether or not someone actually belongs to a local house of worship. is a term that can mean actual membership in a church or synagogue, or just a stated identification with a particular religion whether or not someone actually belongs to a local house of worship. Another term for religious affiliation is religious preferenceA synonym for religious affiliation.. Recall from the Pew survey cited earlier that 83% of Americans express a religious preference, while 61% are official members of a local house of worship. As these figures indicate, more people identify with a religion than actually belong to it.

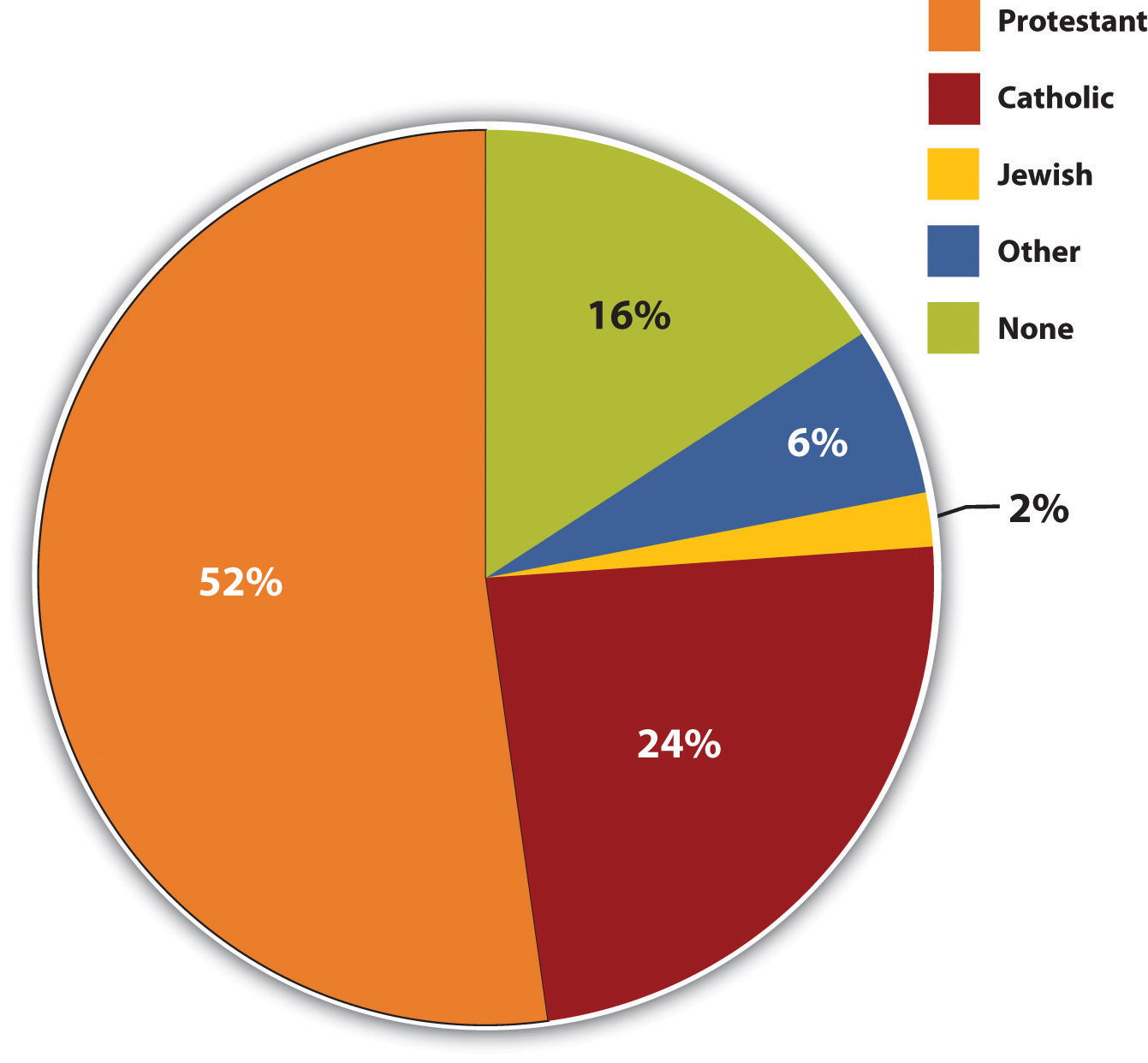

The Pew survey also included some excellent data on religious identification (see Figure 17.1 "Religious Preference in the United States"). Slightly more than half of Americans say their religious preference is Protestant, while about 24% call themselves Catholic. Almost 2% say they are Jewish, while 6% state another religious preference and 16% say they have no religious preference. Although Protestants are thus a majority of the country, the Protestant religion includes several denominations. About 34% of Protestants are Baptists; 12% are Methodists; 9% are Lutherans; 9% are Pentecostals; 5% are Presbyterians; and 3% are Episcopalians. The remainder identify with other Protestant denominations or say their faith is nondenominational. Based on their religious beliefs, Episcopalians, Presbyterians, and Congregationalists are typically grouped together as Liberal Protestants; Methodists, Lutherans, and a few other denominations as Moderate Protestants; and Baptists, Seventh-Day Adventists, and many other denominations as Conservative Protestants.

Figure 17.1 Religious Preference in the United States

Source: Data from Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life. (2008). U.S. religious landscape survey. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center.

The religious affiliations just listed differ widely in the nature of their religious belief and practice, but they also differ in demographic variables of interest to sociologists (Finke & Stark, 2005).Finke, R., & Stark, R. (2005). The churching of America: Winners and losers in our religious economy (2nd ed.). New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. For example, Liberal Protestants tend to live in the Northeast and to be well educated and relatively wealthy, while Conservative Protestants tend to live in the South and to be less educated and working-class. In their education and incomes, Catholics and Moderate Protestants fall in between these two groups. Like Liberal Protestants, Jews also tend to be well educated and relatively wealthy.

Race and ethnicity are also related to religious affiliation. African Americans are overwhelmingly Protestant, usually Conservative Protestants (Baptists), while Latinos are primarily Catholic. Asian Americans and Native Americans tend to hold religious preferences other than Protestant, Catholic, or Jewish.

Age is yet another factor related to religious affiliation, as older people are more likely than younger people to belong to a church or synagogue. As young people marry and “put roots down,” their religious affiliation increases, partly because many wish to expose their children to a religious education. In the Pew survey, 25% of people aged 18–29 expressed no religious preference, compared to only 8% of those 70 or older.

People can belong to a church, synagogue, or mosque or claim a religious preference, but that does not necessarily mean they are very religious. For this reason, sociologists consider religiosityThe significance of religion in a person’s life., or the significance of religion in a person’s life, an important topic of investigation.

Religiosity has a simple definition but actually is a very complex topic. What if someone prays every day but does not attend religious services? What if someone attends religious services but never prays at home and does not claim to be very religious? Someone can pray and read a book of scriptures daily, while someone else can read a book of scriptures daily but pray only sometimes. As these possibilities indicate, a person can be religious in some ways but not in other ways.

For this reason, religiosity is best conceived of as a concept involving several dimensions: experiential, ritualistic, ideological, intellectual, and consequential (Stark & Glock, 1968).Stark, R., & Glock, C. Y. (1968). Patterns of religious commitment. Berkeley: University of California Press. Experiential religiosity refers to how important people consider religion to be in their lives and is the dimension used by the international Gallup Poll discussed earlier. Ritualistic religiosity refers to the extent of their involvement in prayer, reading a book of scriptures, and attendance at a house of worship. Ideological religiosity involves the degree to which people accept religious doctrine and includes the nature of their belief in a deity, while intellectual religiosity concerns the extent of their knowledge of their religion’s history and teachings. Finally, consequential religiosity refers to the extent to which religion affects their daily behavior.

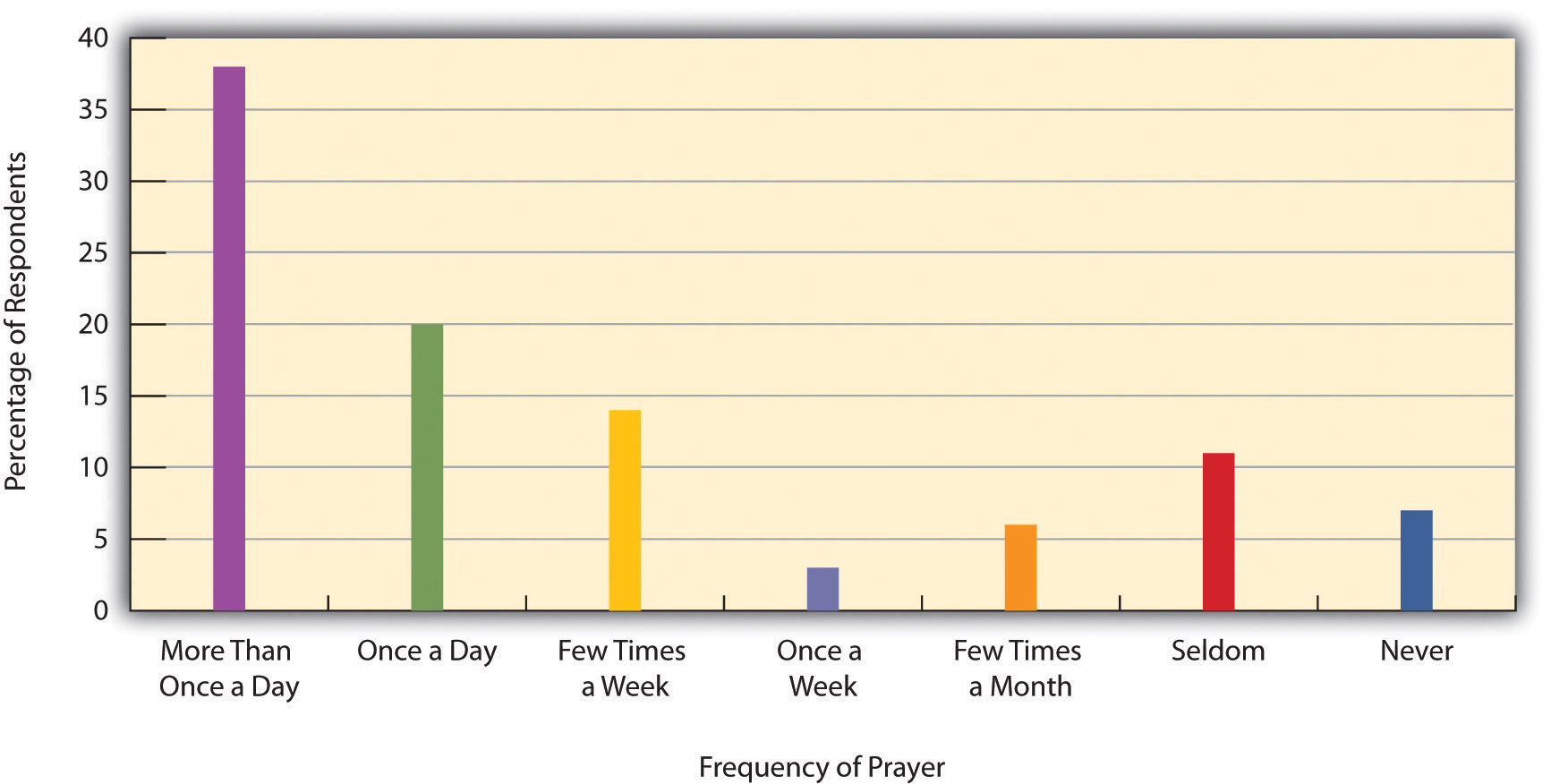

National data on prayer are perhaps especially interesting (see Figure 17.2 "Frequency of Prayer"), as prayer occurs both with others and by oneself. Almost 60% of Americans say they pray at least once daily outside religious services, and only 7% say they never pray (Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life, 2008).Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life. (2008). U.S. religious landscape survey. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Women are more likely than men to pray daily: 66% of women say they pray daily, versus only 49% of men. Daily praying is also more common among older people than younger people, among African Americans than whites, and among people without a college degree than those with a college degree. As these demographic differences indicate, the social backgrounds of Americans affect this important dimension of their religiosity.

Figure 17.2 Frequency of Prayer

Source: Data from Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life. (2008). U.S. religious landscape survey. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center.

When we try to determine why some people are more religious than others, we are treating religiosity as a dependent variable. But religiosity itself can also be an independent variable, as it affects attitudes on a wide range of social, political, and moral issues. Generally speaking, the more religious people are, the more conservative their attitudes in these areas (Adamczyk & Pitt, 2009).Adamczyk, A., & Pitt, C. (2009). Shaping attitudes about homosexuality: The role of religion and cultural context. Social Science Research, 38(2), 338–351. An example of this relationship appears in Table 17.2 "Frequency of Prayer and Belief That Homosexual Sex Is “Always Wrong”", which shows that people who pray daily are much more opposed to homosexual sex. The relationship in the table once again provides clear evidence of the sociological perspective’s emphasis on the importance of social backgrounds for attitudes.

Table 17.2 Frequency of Prayer and Belief That Homosexual Sex Is “Always Wrong”

| Several times a day | Once a day | Several times a week | Once a week | Less than once a week | Never | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage saying “always wrong” | 74.3 | 57.4 | 44.9 | 44.0 | 29.1 | 26.4 |

Source: Data from General Social Survey, 2008.

While religiosity can affect attitudes on various issues, it can also affect behavior and health. The “Sociology Making a Difference” box discusses the effects that religiosity may have.

The Benefits of Religiosity

As discussed earlier, Durkheim considered religion a moral force for socialization and social bonding. Building on this insight, sociologists and other scholars have thought that religiosity might reduce participation in “deviant” behaviors such as drinking, illegal drug use, delinquency, and certain forms of sexual behavior. A growing body of research, almost all of it on adolescents, finds that this is indeed the case. Holding other factors constant, more religious adolescents are less likely than other adolescents to drink and take drugs, to commit various kinds of delinquency, to have sex during early adolescence or at all, and to have sex frequently if they do start having sex (Regenerus, 2007).Regenerus, M. D. (2007). Forbidden fruit: Sex & religion in the lives of American teenagers. New York, NY: Oxford Univeristy Press.

There is much less research on whether this relationship continues to hold true during adulthood. If religion might have more of an impact during adolescence, an impressionable period of one’s life, then the relationship found during adolescence may not persist into adulthood. However, two recent studies did find that more religious, unmarried adults were less likely than other unmarried adults to have premarital sex partners (Barkan, 2006; Uecker, 2008).Barkan, S. E. (2006). Religiosity and premarital sex during adulthood. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 45, 407–417; Uecker, J. E. (2008). Religion, pledging, and the premarital sexual behavior of married young adults. Journal of Marriage and Family, 70(3), 728–744. These results suggest that religiosity may indeed continue to affect sexual behavior and perhaps other behaviors during adulthood.

Sociologists and other scholars have also built on Durkheim’s insights to assess whether religious involvement promotes better physical health and psychological well-being. As the earlier discussion of religion’s functions noted, a growing body of research finds that various measures of religious involvement, but perhaps especially attendance at religious services, are positively associated with better physical and mental health. Religious involvement is linked in many studies to lower rates of cardiovascular disease, hypertension (high blood pressure), and mortality (Ellison & Hummer, 2010; Green & Elliott, 2010).Ellison, C. G., & Hummer, R. A. (Eds.). (2010). Religion, families, and health: Population-based research in the United States. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; Green, M., & Elliott, M. (2010). Religion, health, and psychological well-being. Journal of Religion & Health, 49(2), 149–163. doi:10.1007/s10943-009-9242-1 It is also linked to higher rates of happiness and lower rates of depression and anxiety.

These effects are thought to stem from several reasons. First, religious attendance increases social ties that provide emotional and practical support when someone has various problems and that also raise one’s self-esteem. Second, personal religious belief can provide spiritual comfort in times of trouble. Third, and as noted in the preceding section, religious involvement promotes healthy lifestyles for at least some people, including lower use of tobacco, alcohol, and other drugs, and reduces the frequency of other risky behaviors such as gambling and unsafe sex. Lower participation in all of these activities helps in turn to increase one’s physical and mental health.

In sum, research increasingly suggests that religiosity helps reduce risky, deviant behaviors and increase physical and psychological well-being. Although religion should not be forced on anyone, this body of research suggests that efforts that promote religiosity among both adolescents and adults may have the benefits just described. For example, older adults often have trouble traveling to a house of worship, whether they live at home or in an institutional setting such as a nursing home or assisted living center. Their well-being may be enhanced if they are provided free or low-cost transportation to attend a house of worship or if regular religious services are begun in the institutional settings that do not already have them. In helping demonstrate the benefits of religiosity in the areas discussed here, sociology has again made a difference.

Although the United States is a fairly religious nation, Americans “are also deeply ignorant about religion,” according to a recent news report (Goodstein, 2010, p. A17).Goodstein, L. (2010, September 28). Basic religion test stumps many Americans. The New York Times, p. A17. The report was based on a 2010 survey by the Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life of more than 3,400 U.S. residents. The survey respondents were asked 32 questions, mostly multiple-choice, about the Bible, the world’s major religions, celebrated religious figures from various points in world history, and what U.S. Supreme Court rulings permit in the public practice of religion. Among other questions, respondents were asked what Ramadan is, where Jesus was born, who led the exodus out of Egypt in the Bible, and whose writings started the Protestant Reformation; they were also asked to identify the religious preference of the Dalai Lama, Joseph Smith, and Mother Teresa.

The average respondent provided correct answers to only half the questions. Researchers considered most of the questions to be fairly easy, but a few of the questions were fairly difficult.

For example, whereas 89% of respondents knew that teachers in public schools may not lead a class in prayer and 71% knew that Jesus was born in Bethlehem, only 54% knew that the Koran is the Islamic holy book, only 45% knew that the Jewish Sabbath begins on Friday, and only 23% knew that teachers in public schools are allowed to read from the Bible as an example of literature.

The respondents’ level of education was strongly related to their percentage of correct answers. College graduates answered an average of 20.6 questions correctly, people who had taken only some college courses answered 17.5 questions correctly, and respondents with a high school degree or less answered 12.8 questions correctly. Higher scores were also achieved by respondents who were more religious, by men, by whites, and by non-Southerners (Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life, 2010).Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life. (2010, September 28). U.S. religious knowledge survey. Retrieved from http://www.pewforum.org/Other-Beliefs-and-Practices/U-S-Religious-Knowledge-Survey.aspx

During the last decade, the Higher Education Research Institute (HERI) at the University of California, Los Angeles, conducted a national longitudinal survey of college students’ religiosity and religious beliefs (Astin, Astin, & Lindholm, 2010).Astin, A. W., Astin, H. S., & Lindholm, J. A. (2010). Cultivating the spirit: How college can enhance students’ inner lives. Hoboken NJ: Jossey-Bass. They interviewed more than 112,000 entering students in 2004 and more than 14,000 of these students in spring 2007 toward the end of their junior year. This research design enabled the researchers to assess whether and how various aspects of religious belief and religiosity change during college. Several findings were notable.

First, religious commitment (measures of the students’ assessment of how important religion is to them) stayed fairly stable during college. Students who drank alcohol and partied the most were more likely to experience a decline in religious commitment, although a cause-and-effect relationship here is difficult to determine.

Second, religious engagement (measures of religious services attendance, praying, religious singing, and reading sacred texts) declined during the college years. This decline was especially steep for religious attendance. Almost 40% of juniors reported less frequent attendance than during their high school years, while only 7% reported more frequent attendance.

Third, religious skepticism (measures of how well religion explains various phenomena compared to science) stayed fairly stable. Skepticism tended to rise among students who partied a lot, went on a study-abroad program, and attended a college with students who were very liberal politically.

Fourth, religious/social conservatism (views on such things as abortion, casual sex, and atheism) tended to decline during college, although the decline was not at all steep. This set of findings is in line with the research discussed earlier showing that students tend to become more liberal during their college years. To the extent students’ views became more liberal, the beliefs of their friends among the student body mattered much more than the beliefs of their faculty.

Fifth, religious struggle (measures of questioning one’s religious beliefs, disagreeing with parents about religion, feeling distant from God, and the like) tended to increase during college. This increase was especially high at campuses where a higher proportion of students were experiencing religious struggle when they entered college. Students who drank alcohol and watched television more often and who had a close friend or family member die were more likely to experience religious struggle, although a cause-and-effect relationship is again difficult to determine.

Because religion is such an important part of our society, sociologists and other observers have examined how religious thought and practice have changed in the last few decades. Two trends have been studied in particular: (a) secularization and (b) the rise of religious conservatism.

SecularizationThe weakening importance of religion in a society. refers to the weakening importance of religion in a society. It plays less of a role in people’s lives, as they are less guided in their daily behavior by religious beliefs. The influence of religious organizations in society also declines, and some individual houses of worship give more emphasis to worldly concerns such as soup kitchens than to spiritual issues. There is no doubt that religion is less important in modern society than it was before the rise of science in the 17th and 18th centuries. Scholars of religion have tried to determine the degree to which the United States has become more secularized during the last few decades (Finke & Stark, 2005; Fenn, 2001).Finke, R., & Stark, R. (2005). The churching of America: Winners and losers in our religious economy (2nd ed.). New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; Fenn, R. K. (2001). Beyond idols: The shape of a secular society. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

The best evidence shows that religion has declined in importance since the 1960s but still remains a potent force in American society as a whole and for the individual lives of Americans (Finke & Scheitle, 2005).Finke, R., & Scheitle, C. (2005). Accounting for the uncounted: Computing correctives for the 2000 RCMS data. Review of Religious Research, 47, 5–22. Although membership in mainstream Protestant denominations has declined since the 1960s, membership in conservative denominations has risen. Most people (92% in the Pew survey) still believe in God, and, as already noted, more than half of all Americans pray daily.

Scholars also point to the continuing importance of civil religionThe devotion of a nation’s citizens to their society and government., or the devotion of a nation’s citizens to their society and government (Santiago, 2009).Santiago, J. (2009). From “civil religion” to nationalism as the religion of modern times: Rethinking a complex relationship. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 48(2), 394–401. In the United States, love of country—patriotism—and admiration for many of its ideals are widespread. Citizens routinely engage in rituals, such as reciting the Pledge of Allegiance or singing the national anthem, that express their love of the United States. These beliefs and practices are the secular equivalent of traditional religious beliefs and practices and thus a functional equivalent of religion.

The rise of religious conservatism also challenges the notion that secularization is displacing religion in American life. Religious conservatismIn the U.S. context, the belief that the Bible is the actual word of God. in the U.S. context is the belief that the Bible is the actual word of God. As noted earlier, religious conservatism includes the various Baptist denominations and any number of evangelical organizations, and its rapid rise was partly the result of fears that the United States was becoming too secularized. Many religious conservatives believe that a return to the teachings of the Bible and religious spirituality is necessary to combat the corrupting influences of modern life (Almond, Appleby, & Sivan, 2003).Almond, G. A., Appleby, R. S., & Sivan, E. (2003). Strong religion: The rise of fundamentalisms around the world. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Today about one-third of Americans state a religious preference for a conservative denomination (Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life, 2008).Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life. (2008). U.S. religious landscape survey. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Because of their growing numbers, religious conservatives have been the subject of increasing research. They tend to hold politically conservative views on many issues, including abortion and the punishment of criminals, and are more likely than people with other religious beliefs to believe in such things as the corporal punishment of children (Burdette, Ellison, & Hill, 2005).Burdette, A. M., Ellison, C. G., & Hill, T. D. (2005). Conservative protestantism and tolerance toward homosexuals: An examination of potential mechanisms. Sociological Inquiry, 75(2), 177–196. They are also more likely to believe in traditional roles for women.

Closely related to the rise of religious conservatism has been the increasing influence of what has been termed the “new religious right” in American politics (Martin, 2005; Capps, 1990; Moen, 1992).Martin, W. C. (2005). With God on our side: The rise of the religious Right in America. New York, NY: Broadway Books; Capps, W. H. (1990). The new religious Right: Piety, patriotism, and politics. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press; Moen, M. (1992). The transformation of the Christian Right. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press. Since the 1980s, the religious right has been a potent force in the political scene at both the national and local levels, with groups like the Moral Majority and the Christian Coalition effective in raising money, using the media, and lobbying elected officials. As its name implies, the religious right tries to advance a conservative political agenda consistent with conservative religious concerns. Among other issues, it opposes legal abortion, gay rights, and violence and sex in the media, and it also advocates an increased religious presence in public schools. Although the influence of the religious right has waned since the 1990s, its influence on American politics is bound to be controversial for many years to come.

Sociological theory and research are relevant for understanding and addressing certain religious issues. One major issue today is religious intolerance. Émile Durkheim did not stress the hatred and conflict that religion has promoted over the centuries, but this aspect of conflict theory’s view of religion should not be forgotten. Certainly religious tolerance should be promoted among all peoples, and strategies for doing so include education efforts about the world’s religions and interfaith activities for youth and adults. The Center for Religious Tolerance (http://www.c-r-t.org/index.php), headquartered in Sarasota, Florida, is one of the many local and national organizations in the United States that strive to promote interfaith understanding. In view of the hostility toward Muslims that increased in the United States after 9/11, it is perhaps particularly important for education efforts and other activities to promote understanding of Islam.

Religion may also help address other social issues. In this regard, we noted earlier that religious belief and practice seem to promote physical health and psychological well-being. To the extent this is true, efforts that promote the practice of faith may enhance one’s physical and mental health.. In view of the health problems of older people and also their greater religiosity, some scholars urge that such efforts be especially undertaken for people in their older years (Moberg, 2008).Moberg, D. O. (2008). Spirituality and aging: Research and implications. Journal of Religion, Spirituality & Aging, 20, 95–134. We also noted that religiosity helps reduce drinking, drug use, and sexual behavior among adolescents and perhaps among adults. This does not mean that religion should be forced on anyone against his or her will, but this body of research does suggest that efforts by houses of worship to promote religious activities among their adolescents and younger children may help prevent or otherwise minimize risky behaviors during this important period of the life course.