Source: Photo courtesy of cloudsoup, http://www.flickr.com/photos/cloudsoup/2762796137/.

Chef Robert Irvine’s résumé was impressive. According to the St. Petersburg Times, he advertised his experience as including:

The truth—when the newspaper revealed it on a splashy front-page article—wasn’t quite so overpowering:

After the truth came out, Chef Irvine was fired from his popular TV show on the Food Network, Dinner: Impossible. A few months later, however, after the scandal blew over and he’d corrected his résumé, he reapplied for his old job, was rehired, and he’s on TV today.

The five types of positive résumé misrepresentations are

Negative résumé misrepresentations have also been discussed. Looking back at Irvine’s résumé adventure, can you label each of his transgressions?

The Internet site Fakeresume.com includes the following advice for job seekers: “Hiring Managers Think You’re Lying Anyway!! Yep that’s right, the majority of human resources managers assume that EVERYONE embellishes, exaggerates, puffs up and basically lies to some extent on your résumé. So if you’re being totally honest you’re being penalized because they’re going to assume that you embellished your résumé to a certain extent!”Fakeresume.com, accessed May 17, 2011, http://fakeresume.com.

Assume you believe this is true, can you make the ethical case for being honest on your résumé regardless of what hiring managers think?

Source: Photo courtesy of Tomáš Obšívač, http://www.flickr.com/photos/toob/38893762/.

An Internet posting carries a simple Q&A thread: someone’s searching for a good upholstery shop in Maryland. An unexpected answer comes back from Fenny L: criminals. A local jail has a job-training program for their inmates and they contract the men at $1.50 per hour.Fenny L., April 7, 2009, “Searching for good upholstery shop in MD,” accessed May 17, 2011, http://www.yelp.com/topic/gaithersburg-searching-for-good-upholstery- shop-in-md.

The responses to the suggestion are intense and all over the place, but many circle around the ethics of the numbingly low wage, leading Fenny L to introduce a new thread. Here are the three main points she makes.

Suppose you made a mistake and ended up in jail for a few months. While there, you participated in this program. Now you’re out and seeking an upholstering job.

Sometimes a split opens between a community-wage level (what people in general in a certain place are paid for certain labor) and an organizational-wage level (what people at a specific organization are paid for the same labor). The split clearly opens here; the prisoners are paid much less than other upholsterers in the larger community.

Fenny L. believes the workers are receiving a fair wage because they’re getting valuable training and experience that will improve their future job prospects. That’s probably true, but the fact remains that the workers are being paid much less money, for the same work, than others.

Source: Photo courtesy of Henk de Vries, http://www.flickr.com/photos/henkdevries/2662269430/.

In his book 21 Dirty Tricks at Work, author Colin Gautrey gives his readers a taste of how intense life at the office can get. Here are two of his favorite tricks.“21 Dirty Tricks,” The Gautrey Group, accessed May 17, 2011, http://www.siccg.com/fre/DirtyTricks.php.

The exposure trick. Coercing a coworker by threatening to make public a professional or personal problem

If you’re angling for a raise, and you know something damaging about your supervisor, you may be tempted by the tactic of exposure. Imagine you know that your supervisor has a prescription drug habit and it’s getting worse. Her performance at the office has been imbalanced but not so erratic as to raise suspicions. You plan to confront her and say you’ll spill the beans unless she gets you a raise. Whose interests are involved here? What responsibilities do you have to each of them? What ethical justification could you draw up to justify your threat?

The bystander trick. Knowing that someone is in trouble but standing on the sidelines and doing nothing even when intervention is clearly appropriate and would be helpful to the business

At an upholstering company you’re in competition for a promotion with a guy who learned the craft in jail, through the Department of Corrections’ job-training course. He hadn’t revealed that fact to anyone, but now the truth has come to light. You’ve worked with him on a lot of assignments and seen that he’s had a chance to make off with some decent jewelry but hasn’t taken anything. You could speak up to defend him, but you’re tempted to use the bystander trick to increase the odds that you’ll win the duel. What ethical argument could you draw up to convince yourself that you shouldn’t stand there and watch, but instead you should help your adversary out of the jam?

Source: Photo courtesy of Alex Johnson, http://www.flickr.com/photos/89934978@N00/2997961865/.

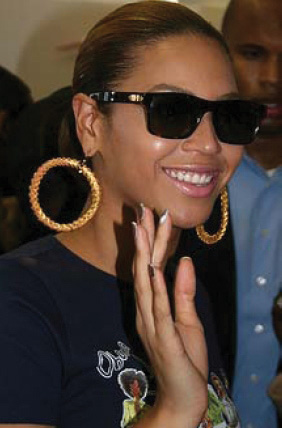

The R&B group Destiny’s Child was composed of Beyoncé Knowles, Kelly Rowland, and Michelle Williams. They started slow in 1990 (Beyoncé was nine), giving miniconcerts in crumbling dance halls around Houston, and then kept at it through small-time talent shows, promised record deals that never materialized, and the disintegration of Rowland’s family (Beyoncé’s parents took her into their home). They finally got a crummy but real record deal in 1998 and made the most of it.

By 2002 they’d become a successful singing and dance act. But soon after, they broke up under the pressure of Beyoncé’s solo career, which seemed to be speeding even faster than the group effort.

In 2004 they reunited for a new album, Destiny Fulfilled, which went triple platinum. On the European leg of the subsequent world tour, Beyoncé quit more definitively. She took the fan base with her and began evolving into the hugely successful Beyoncé we know now: pop music juggernaut, movie celebrity, clothing design star.…The other two members of the original group? Today they appear on B-list talk shows (when they can get booked) and are presented to viewers as Kelly Rowland, formerly of Destiny’s Child, and Michelle Williams, formerly of Destiny’s Child.

According to the New York Times it shouldn’t be surprising that things ended up this way: “It’s been a long-held belief in the music industry that Destiny’s Child was little more than a launching pad for Beyoncé Knowles’s inevitable solo career.”Lola Ogunnaike, “Beyoncé’s Second Date with Destiny’s Child,” New York Times, November 14, 2004, accessed May 17, 2011, http://www.nytimes.com/2004/11/14/arts/music/14ogun.html?_r=1.

Which leads to this question: Why did she go back in 2004 and do the Destiny Fulfilled album with her old partners? Here’s what the New York Times reported: “Margeaux Watson, arts and entertainment editor at Suede, a fashion magazine, suggests that the star does not want to appear disloyal to her former partners, and called Beyoncé’s decision to return to the group a charitable one.” But “from Day 1, it’s always been about Beyoncé,” Ms. Watson said. “She’s the one you can’t take your eyes off of; no one really cares about the other girls. I think Beyoncé will eventually realize that these girls are throwing dust on her shine.”Lola Ogunnaike, “Beyoncé’s Second Date with Destiny’s Child,” New York Times, November 14, 2004, accessed May 17, 2011, http://www.nytimes.com/2004/11/14/arts/music/14ogun.html?_r=1.

Destiny’s Child rolled money in, and it needed to be divided up. Assume the three singers always split money equally, going way back to 1990 when it wasn’t the profits they were dividing but the costs of gasoline and hotel rooms, which added up to more than they got paid for performing. About the money that finally started coming in faster than it was going out, here are two common theories for justifying the payment of salaries within an organization: Money is apportioned according to the worker’s value to the organization, and money is apportioned according to the experience and seniority relative to others in the organization.

There are a lot of rhythm and blues groups out there, singing as hard as they can most nights on grimy stages for almost no audience, which means the organizational-wage level of Destiny’s Child was way, way above the wage level of other organizations in the same line of work.

Destiny’s Child was a pop group; their hits included “Say My Name,” which isn’t too different from Beyoncé’s smash “Single Ladies (Put a Ring on It).” The videos are pretty close, too: nearly identical mixes of rhythm, dancing, fun, and sexy provocation. After comparing the video of “Say My Name”“Destiny’s Child—Say My Name,” YouTube video, 4:00, posted by “DestinysChildVEVO,” October 25, 2009, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sQgd6MccwZc. with “Single Ladies,”“Beyoncé—Single Ladies (Put A Ring On It),” YouTube video, 3:19, posted by “beyonceVEVO,” October 2, 2009, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4m1EFMoRFvY. it’s hard to deny that Beyoncé benefited from her time in Destiny’s Child. Very possibly, she feels as though she owes Rowland and Williams part of her success, and that’s why she did the reunion record and tour. Now, if you were Rowland or Williams, could you form an ethical argument that Beyoncé owes you more than that based on the following:

Source: Photo courtesy of ctitze, http://www.flickr.com/photos/ctitze/329928527/.

Biswamohan Pani, a low-level engineer at Intel, apparently stole trade secrets worth a billion dollars from the company.

His plot was simple. According to a Businessweek article, he scheduled his resignation from Intel for June 11, 2008. He’d accumulated vacation time, however, so he wasn’t actually in the office during June, even though he officially remained an employee. That employee status allowed him access to Intel’s computer network and sensitive information about next-generation microprocessor prototypes. He downloaded the files, and he did it from his new desk at Advanced Micro Devices (AMD), which is Intel’s chief rival. Pani had simply arranged to begin his new AMD job while officially on vacation from Intel.

Why did he do it? The article speculates that “Pani obtained Intel’s trade secrets to benefit himself in his work at AMD without AMD’s knowledge that he was doing so, which is a fairly frequent impulse among employees changing jobs: to take a bit of work product from their old job with them.”Michael Orey, “Lessons from Intel’s Trade-Secret Case,” Bloomberg Businessweek, November 18, 2008, accessed May 17, 2011, http://www.businessweek.com/print/technology/content/nov2008/tc20081118_067329.htm.

According to Nick Akerman, a New York lawyer who specializes in trade secret cases, “It’s amazing how poorly most companies [protect their trade secrets].”Michael Orey, “Lessons from Intel’s Trade-Secret Case,” Bloomberg Businessweek, November 18, 2008, accessed May 17, 2011, http://www.businessweek.com/print/technology/content/nov2008/tc20081118_067329.htm.

After being caught, Pani faced charges in federal court for trade secret theft, with a possible prison term of ten years. He pleaded innocent, maintaining that he downloaded the material for his wife to use. She was an Intel employee at the time and had no plans to leave.