Tappening is run by a couple of guys who don’t like bottled water. The liquid is fine, but they worry about those small transparent bottles. First, the air gets polluted when they’re fabricated and then, after they’ve been emptied and tossed in the trash, the plastic doesn’t quickly break down and reenter the ecosystem.

The Tappening people also notice that bottled-water advertising can be deceitful. The labels and ad campaigns are known to feature mountain streams in forest paradises, breeding the idea that the water is pumped from pristine natural sources when the truth is a lot of it comes from the tap, usually with some filtering applied.

Faced with the distasteful situation—polluting water bottles and deceitful advertising—the Tappening crew could’ve put together some of their own ads revealing the true source of common bottled waters and the destiny of the containers, but they chose to mount a more aggressive campaign. One effort is a print ad with a crying polar bear drawn at the center, sitting on a melting arctic glacier. Under the title “Bottled Water,” the text says, “98% melted ice caps, 2% polar bear tears.” At the bottom, in small print, a message reads, “If bottled water companies can lie, we can too.”“New Tappening Ads Tell Lies—Honest,” Adweek, July 23, 2009, accessed June 2, 2011, http://www.adweek.com/aw/content_display/creative/news/e3i04ac5aa7296d367cc7c7c9623bc3df48.

In broad strokes, there are four types of deceitful advertising: those that make false claims, conceal facts, make ambiguous claims, and engage in puffery.

Here’s one thing the Tappening polar bear ad neglects to inform people: Tappening isn’t just trying to get us to stop drinking bottled water; they’re also trying to sell something. Water bottles. They cost $14.95 (plus $3 shipping and handling). For the money you get a Tappening plastic bottle made for reuse and emblazoned with the company’s slogan: “Think Global. Drink Local.” You can also buy a message shoulder bag from the company. It announces that it’s “Made with 100% post-consumer recycled materials: yesterday’s discarded bottles and yogurt containers.” That costs $49.95, plus the shipping and handling.Tappening, order page, accessed June 2, 2011, http://www.tappening.com/Order_Tappening_Bottle.

Make the case that Tappening is engaging in deceitful advertising by concealing facts in its polar bear ad. More broadly, what is the ethical case against Tappening?

For consumers, water bottles are not high stakes. If some guy reads the Tappening ad, gets caught up in the message that bottled water is environmentally disastrous (“98% melted ice caps, 2% polar bear tears”), visits the web page and, in the passion of the moment, buys ten reusable water bottles and the shoulder bag, he’ll be out about $250. It’s doubtful that his life will be significantly worsened by that kind of monetary loss. Later on, however, he may feel conned when he realizes that the air was polluted to make his presumably environmentally friendly water bottles, and most of the time when he needs bottled water, it’s not foreseen, and so he ends up just buying the disposable bottles anyway. The reusable containers with their enviro-friendly slogans get left at home and forgotten and the only thing that really changes is the guys at Tappening made some money.

Source: Photo courtesy of Brent Moore, http://www.flickr.com/photos/brent_nashville/166218527/.

Two curious news stories. The first comes from the BBC and tells of a shopaholic, a woman who purchased so much she could hardly fit it all in her apartment. When she passed away from pneumonia, it took more than a day to find her body underneath all the purchases. A friend commented, “It gave her pleasure to buy things, she only bought things she really liked.”“Shopaholic Died under Purchases,” BBC, July 28, 2009, accessed June 2, 2011, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/england/manchester/8173271.stm.

The second story relates that in India, according to a UN report, there are about 560 million cell phone users, but only 360 million people have access to toilets.“India Has More Mobile Phones Than Toilets: UN report,” Telegraph, April 15, 2010, accessed June 2, 2011, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/asia/india/7593567/India-has-more-mobile-phones-than-toilets-UN-report.html.

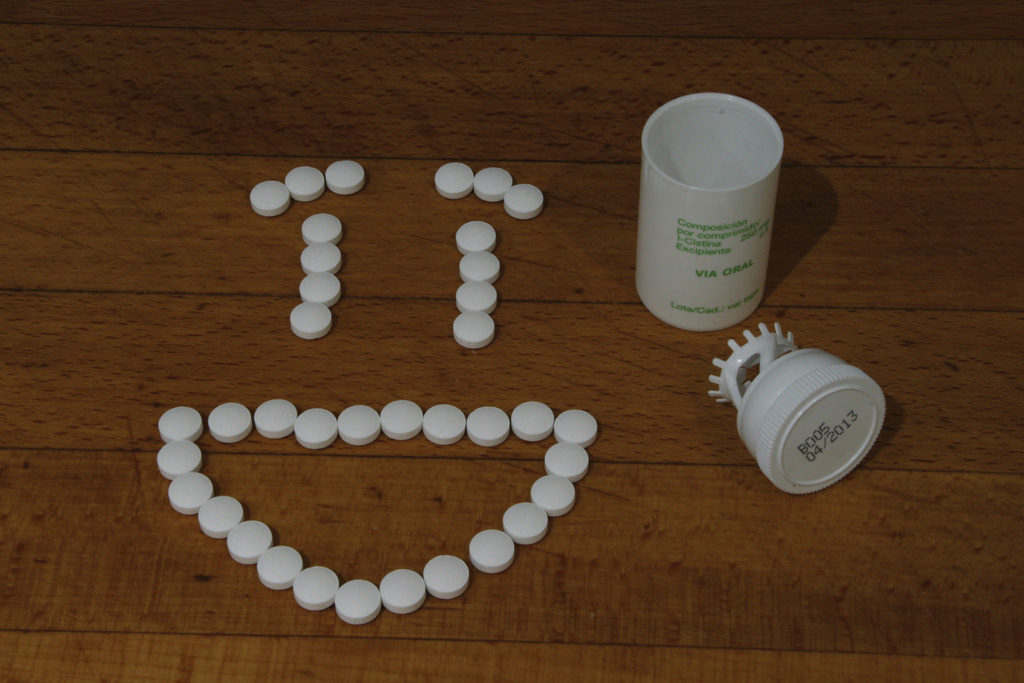

Source: Photo courtesy of Angel Arcones, http://www.flickr.com/photos/freddy-click-boy/3215186647/.

Statistics aren’t available, but the amount of time guys spend spilling seduction lines—and the amount of time women spend dealing with them—is very high. Most women can deal with it coming from most guys, but what happens when the lines come from a powerful corporation?

The giant pharmaceutical company Boehringer Ingelheim has stumbled onto a drug (Flibanserin) that makes women want sex. That’s not going to earn them any money, though. To get sales, they’ve got to convince women that they want to want to have sex. The problem is interesting. The drug company has discovered the cure to a disease that, by definition, no one has. If a woman—or a man—doesn’t feel like having sex, then she doesn’t feel like she’s missing something by not doing it. The opposite is the case. She doesn’t want to do it, so the fact that she doesn’t feel like doing it isn’t a problem at all. It’s perfect, actually. What the company needs to do, therefore, is create a desire. It has to make women want (or even need) something they didn’t know they wanted.

According to the New York Times, “Boehringer has been trying to lay the consumer groundwork with a promotional campaign about women’s low libido, including a Web site, a Twitter feed and a publicity tour by Lisa Rinna, a soap opera star and former Playboy model who describes herself as someone who has suffered from a disorder that Boehringer refers to as a form of ‘female sexual dysfunction.’”Duff Wilson, “Push to Market Pill Stirs Debate on Sexual Desire,” New York Times, June 16, 2010, accessed June 2, 2011, http://www.nytimes.com/2010/06/17/business/17sexpill.html?src=me&ref=business.

That advertising campaign is geared to create a desire for a form of women’s Viagra by convincing women that they’re supposed to want sex, and there’s something wrong with them if they don’t. The effort has its critics. Here’s one argument: “Boehringer’s market campaign could create anxiety among women, making them think they have a condition that requires medical treatment. ‘This is really a classic case of disease branding,’ said Dr. Adriane Fugh-Berman, an associate professor at Georgetown University. ‘The messages are aimed at medicalizing normal conditions, and also preying on the insecurity of the patient.’”Duff Wilson, “Push to Market Pill Stirs Debate on Sexual Desire,” New York Times, June 16, 2010, accessed June 2, 2011, http://www.nytimes.com/2010/06/17/business/17sexpill.html?src=me&ref=business

Dr. Fugh-Berman says that Boehringer’s marketing campaign is “aimed at medicalizing normal conditions.”

The goal of Boehringer’s marketing is to create a desire for a product. There are a number of ethical objections to this kind of campaign.

Boehringer created a web page dedicated to its sex drug—http://www.sexbrainbody.com—which has since been taken down. On it, a successful actress and Playboy model left a testimonial. It concluded with her encouraging readers to learn about sexual health and to feel comfortable talking about it. “Both,” she asserted, “play an important role in overall health and well-being. It’s time to focus on you!”Melissa Castellanos, “Lisa Rinna on ‘Sex, Brain, Body’ Connection,” CBS News, May 18, 2010, accessed June 2, 2011, http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2010/05/18/entertainment/main6496015.shtml?tag=mncol;lst;2.

A New York Times article relates that prestigious medical journals have published research affirming that low libido really is a problem, and one suffered by a large number of women. The article also notes that “such studies have been financed by drug companies.”Duff Wilson, “Push to Market Pill Stirs Debate on Sexual Desire,” New York Times, June 16, 2010, accessed June 2, 2011, http://www.nytimes.com/2010/06/17/business/17sexpill.html?src=me&ref=business.

Source: Photo courtesy of Roger Karlsson, http://www.flickr.com/photos/free-photos/3375886335/.

In a world of get-rich-quick schemes, few are mentioned more frequently than lawsuits. One of the reasons is the infamous McDonald’s coffee case (Liebeck v. McDonald’s Restaurants). This is what happened in 1992 in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Stella Liebeck, seventy-nine, was riding in a car driven by her grandson. They stopped at a McDonald’s drive-through, where she purchased a Styrofoam cup of coffee. Wanting to add cream and sugar, she squeezed the cup between her knees and pulled off the plastic lid. The entire thing spilled back into her lap. The searing liquid left her with extensive third-degree burns. Eight days of hospitalization—which included skin grafts—were required.

Initially, she sought $20,000 from McDonald’s, which was more or less the cost of her medical bills. McDonald’s refused. They went to court. There it came to light that about seven hundred claims had been made by consumers between 1982 and 1992 for similar incidents. This seems to indicate that McDonald’s knew—or at least should have known—that the hot coffee was a problem.

Most of the rest of the case turned around temperature questions. McDonald’s admitted that they served their coffee at 185 degrees, which will burn the mouth and throat and is about 50 degrees higher than typical homemade coffee. More importantly, coffee served at temperatures up to 155 degrees won’t cause burns, but the danger rises abruptly with each degree above that limit. So why did McDonald’s serve it so hot? Most customers, the company claimed, bought on the way to work or home and would drink it on arrival. The high temperature would keep it fresh until then. Unfortunately, internal documents showed that McDonald’s knew their customers intended to drink the coffee in the car immediately after purchase. Next, McDonald’s asserted that their customers wanted their coffee hot. The restaurant conceded, however, that customers were unaware of the serious burn danger and that no adequate warning of the threat’s severity was provided.

Finally, the jury awarded Liebeck $160,000 in compensatory damages and $2.7 million in punitive damages (about two days worth of McDonalds’ coffee sales). The judge, however, reduced the $2.7 million to $480,000. McDonald’s threatened to appeal, and the two sides eventually came to a private settlement agreement.Consumer Attorneys of California, “The Actual Facts About the McDonalds’ Coffee Case,” The ‘Lectric Law Library, 1995, accessed June 2, 2011, http://www.lectlaw.com/files/cur78.htm.

What does caveat emptor mean?

From the information provided, and from your own experience, what are the main terms of the implicit contract surrounding the purchase of coffee at a fast-food drive-through?

In order for an implicit contract to arise, the following three conditions must be met:

Were these three conditions met in the McDonald’s coffee case? Explain.

The concept of manufacturer liability gives consumers the right to sue manufacturers for defective goods. There are three kinds of product defect:

Which (if any) of these defects are applicable in the McDonald’s coffee case? Explain.

Source: Photo courtesy of abaporu, http://www.flickr.com/photos/abaporu/499864635.

This is a condensed version of a dialogue between Vincent Ferrari and AOL, an Internet services provider known especially for its e-mail.

| AOL Rep: | Hi, this is John at AOL. How may I help you today? |

| Vincent: | I wanted to cancel my account. |

| AOL Rep: | OK. You’ve had this account for a long time. |

| Vincent: | Yep! |

| AOL Rep: | You’ve used this quite a bit. What was the cause for turning this off today? |

| Vincent: | I just don’t use it anymore. |

| AOL Rep: | Do you have a high-speed connection like DSL or cable? |

| Vincent: | Yep. |

| AOL Rep: | OK. |

| AOL Rep: | How long have you had that, the high speed? |

| Vincent: | Years. |

| AOL Rep: | Well, actually, I’m showing a lot of usage on this account. |

| Vincent: | Yeah a long time ago, not recently. |

| AOL Rep: | I’m looking at this account… |

| Vincent: | Either way, whatever you’re seeing… |

| AOL Rep: | Well, what’s the cause for turning this off today? |

| Vincent: | I don’t use it. |

| AOL Rep: | Well, OK. Is there a problem with the software itself? |

| Vincent: | No. It’s just I don’t use it. I don’t need it. I don’t want it. I don’t need it anymore. |

| AOL Rep: | So when you use it, the computer, is it for business or for school? |

| Vincent: | Dude, what difference does it make? I don’t want the AOL account anymore. Can you please cancel it? |

| AOL Rep: | Well, on June second this account was signed on. It’s been on for seventy-two hours. |

| Vincent: | I don’t know how to make it any clearer. |

| AOL Rep: | Last year was five hundred fou—last month was 545 hours of usage. |

| Vincent: | I don’t know how to say this any clearer, so I am just going to say this one last time. Cancel the account please. |

| AOL Rep: | Well explain to me what’s—wha—why? |

| Vincent: | I am not explaining anything to you. Cancel the account. |

| AOL Rep: | Wha—what’s the matter man? We’re just—I’m just trying to help. |

| Vincent: | You’re not helping me. You’re not helping me. |

| AOL Rep: | I am trying to, OK. |

| Vincent: | Listen, I called to cancel the account. Helping me would be canceling the account. Please help me and cancel my account. |

| AOL Rep: | No it wouldn’t actually. |

| Vincent: | Cancel my account! |

| AOL Rep: | Turning off your account would be the worst— |

| Vincent: | Cancel the account! Cancel the account! |

| AOL Rep: | Is your dad there? |

| Vincent: | I’m the primary payer. I’m the primary person on the account, not my dad. Cancel the account! |

| AOL Rep: | OK, ’cause I’m just trying to figure out— |

| Vincent: | Cancel the account! I don’t know how to make this any clearer for you. Cancel the account. The card is mine, in my name. The account is mine and in my name. When I say, “cancel the account,” I don’t mean help me figure out how to keep it. Cancel the account. |

This went on for almost five minutes. Part of the audio can be heard here:

Cancel AOL

Back in the days before Internet, exchanges like this would’ve been entirely positive for AOL. The worst that could’ve happened is that the company would lose the client, who they were going to lose anyway. By dragging the cancellation out, they may have convinced him to stay on, so that’s what they did.

Today, with Internet, things are different. Ferrari (who, apparently, suspected that AOL would try some shenanigans) taped the conversation and posted it. The Slashdot effect—a website overwhelmed by a huge spike in traffic—followed immediately. It wasn’t long before Ferrari and his conversation were appearing on shows like Today. The damage to the AOL brand was catastrophic. Revenue plummeted, and with no hope for recovery, the company that owned and controlled AOL at the time, Time Warner, sold off the shriveled remains.

Certainly, the Ferrari tape didn’t alone bring down AOL, not even close, but it’s difficult for any company to be profitable when recordings like Ferrari’s are going out over national TV and available for anyone to hear, twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, forever, online.

As an ethical theory, most conceptions of retributive justice highlight a notion of proportionality.