Source: Photo courtesy of emdot, http://www.flickr.com/photos/emdot/22751767.

Earl Grinols and David Mustard are economists and, like a lot of people, intrigued by both casinos and crime. In their case, they were especially curious about whether the first causes the second. It does, according to their study. Eight percent of crime occurring in counties that have casinos results from the legalized gambling. In strictly financial terms—which are the ones they’re comfortable with as economists—the cost of casino-caused crime is about $65 per adult per year in those counties.Earl Grinols and David Mustard, “Measuring Industry Externalities: The Curious Case of Casinos and Crime,” accessed June 7, 2011, http://casinofacts.org/casinodocs/Grinols-Mustard-Casinos_And_Crime.pdf.

When casinos come to town, the following specific crimes increase:

The crimes also increased to some extent in neighboring counties.

Situation: A casino regular runs out of money after a string of bad cards. She coasts out to the street and drops her purse in front of an out-of-towner. When the chivalrous guy bends over to pick it up for her, she picks his back pocket. With the $100 stolen from the wallet, she heads back into the casino, spends $40 on hard liquor, loses the rest at the roulette table, and goes home. She wakes up alone, though some underwear she finds on her floor makes her think she probably didn’t start the night that way. She can’t remember.

Sole proprietorship

Partnership

Nonprofit organization

Large, public corporation

Pigouvian taxes (named after economist Arthur Pigou, a pioneer in the theory of externalities) attempts to correct externalities—and so formalize a corporate social responsibility—by levying a tax equal to the costs of the externality to society. The casino, in other words, that causes crime and other problems costing society, say, $1 million should pay a $1 million tax.

Source: Photo courtesy of Andre Chinn, http://www.flickr.com/photos/andrec/2608065730.

The W. R. Grace Company was founded by, yes, a man named W. R. Grace. He was Irish and it was a shipping enterprise he brought to New York in 1865. Energetic and ambitious, while his company grew on one side, he was getting civically involved on the other. Fifteen years after arriving, he was elected Mayor of New York City. Five years after that, he personally accepted a gift from a delegation representing the people of France. It was the Statue of Liberty.

Grace was a legendary philanthropist. He provided massive food donations to his native Ireland to relieve famine. At home, his attention focused on his nonprofit Grace Institute, a tuition-free school for poor immigrant women. The classes offered there taught basic skills—stenography, typewriting, bookkeeping—that helped students enter the workforce. More than one hundred thousand young women have passed through the school, which survives to this day.

In 1945, grandson J. Peter Grace took control of the now worldwide shipping company. A decade later, it became a publicly traded corporation on the New York Stock Exchange. The business began shifting from shipping to chemical production.

By the 1980s, W. R. Grace had become a chemical and materials company, and it had come to light that one of its plants had been pouring toxins into the soil and water underneath the small town of Woburn, Massachusetts. The poisons worked their way into the town’s water supply and then into the townspeople. It caused leukemia in newborns. Lawsuits in civil court, and later investigations by the Environmental Protection Agency, cost the corporation millions.

J. Peter Grace retired as CEO in 1992. After forty-eight years on the job, he’d become the longest-reigning CEO in the history of public companies. During that time, he also served as president of the Grace Institute.

The nonfiction novel A Civil Action came out in 1996. The best-selling, award-winning chronicle of the Woburn disaster soon became a Hollywood movie. The movie, starring John Travolta, continues to appear on television with some regularity.

To honor the Grace Institute, October 28 was designated “Grace Day” by New York City in 2009. On that day, the institute defined its mission this way: “In the tradition of its founding family, Grace Institute is dedicated to the development of the personal and business skills necessary for self-sufficiency, employability, and an improved quality of life.”“Our Mission,” Grace Institute, accessed June 1, 2011, http://www.graceinstitute.org/mission.asp.

The specific theory of corporate social responsibility encompasses four kinds of obligations: economic, legal, ethical, and philanthropic.

The triple-bottom-line theory of corporate responsibility promotes three kinds of sustainability: economic, social, and environmental.

Stakeholder theory affirms that for companies to perform ethically, management decisions must take account of and respond to stakeholder concerns.

There are a number of arguments supporting the proposal that corporations are autonomous entities (apart from owners and directors and employees) with ethical obligations in the world. The moral requirement argument contains four elements:

How can each of these general arguments be specified in the case of W. R. Grace?

Source: Photo courtesy of the Italian Voice, http://www.flickr.com/photos/desiitaly/2254327579.

The Body Shop is a cosmetics firm out of England, founded by Anita Roddick. “If business,” she writes on the company’s web page, “comes with no moral sympathy or honorable code of behaviors, then God help us all.”“Our Values,” The Body Shop, accessed June 7, 2011, http://www.thebodyshop.com/_en/_ww/services/aboutus_values.aspx.

Moral sympathy and an honorable code of behaviors has certainly helped The Body Shop. Constantly promoted as an essential aspect of the company and a reason to buy its products, the concept of corporate social responsibility has been a significant factor in the conversion of a single small store in England to a multinational conglomerate.

Maybe it has been too significant a factor. That’s certainly the suspicion of many corporate watchers. The suspicion isn’t that the actual social responsibility has been too significant but that the actions of corporate responsibility have been much less energetic than their promotion. The social responsibility has been, more than anything else, a marketing strategy. Called greenwashing, the accusation is that only minimally responsible actions have been taken by The Body Shop, just enough to get some good video and mount a loud advertising campaign touting the efforts. Here’s the accusation from a website called thegoodhuman.com:

The Body Shop buys the palm oil for their products from an organization that pushed for the eviction of peasant families to develop a new plantation. So much for their concern about creating “sustainable trading relationships with disadvantaged communities around the world.”“Greenwash of the Week: The Body Shop Business Ethics,” The Good Human, September 30, 2009, accessed June 7, 2011, http://www.thegoodhuman.com/2009/09/30/greenwash-of-the-week-the-body-shop-business-ethics.

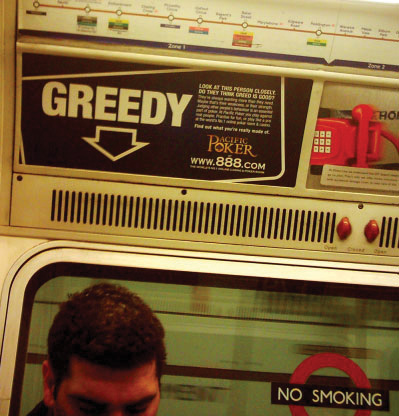

Source: Photo courtesy of the Annie Mole, http://www.flickr.com/photos/anniemole/2750611025.

It’s probably the most repeated business ethics line in recent history. Michael Douglas—playing Wall Street corporate raider Gordon Gekko—stands in front of a group of shareholders at Teldar Paper and announces, “Greed is good.”

Teldar has been losing money, but the company, Douglas believes, is fundamentally strong. The problem’s the management; it’s the CEO and chief operations officer and all their various vice presidents. Because they don’t actually own the company, they only run it, they’re tempted to use the giant corporation to make their lives comfortable instead of winning profits for the actual owners, the shareholders. As one of those shareholders, Douglas is proposing a revolt: get rid of the lazy executives and put in some new directors (like Douglas’s friends) who actually want to make money. Here’s the pitch. Douglas points at the CEO and the rest of the management team up at their table:

All together, these men sitting up here own less than 3 percent of the company. And where does the CEO put his million-dollar salary? Not in Teldar stock; he owns less than 1 percent.

Dramatic pause. Douglas earnestly faces his fellow shareholders.

You own the company. That’s right—you, the stockholder. And you’re all being royally screwed over by these bureaucrats with their steak lunches, their hunting and fishing trips, their corporate jets and golden parachutes. Teldar Paper has 33 different vice presidents, each earning over 200 thousand dollars a year. Now, I have spent the last two months analyzing what all these guys do, and I still can’t figure it out. One thing I do know is that our paper company lost 110 million dollars last year. The new law of evolution in corporate America seems to be survival of the unfittest. Well, in my book you either do it right or you get eliminated.

He adds,

In the last seven deals that I’ve been involved with, there were 2.5 million stockholders who have made a pretax profit of 12 billion dollars.Wall Street, directed by Oliver Stone (Los Angeles: Twentieth Century Fox, 1987), film.

Douglas says, “In my book you either do it right or you get eliminated.”

In the real world, the paper company Weyerhaeuser promotes itself as socially and environmentally responsible. On their web page, they note that they log the wood for their paper from certified forests at a percentage well above that required by law.“Forest Certification,” Weyerhaeuser, accessed June 7, 2011, http://www.weyerhaeuser.com/Sustainability/Footprint/Certification. Carefully defining a “certified forest” would require pages, but basically the publicly held corporation is saying that they don’t just buy land, clear-cut everything, and then move on. Instead, and at a cost to themselves, they leave some trees uncut and plant others to ensure that the forest they’re cutting retains its character.

According to the Weyerhaeuser web page, the US government sets certain rules for sustainability with respect to forests. Weyerhaeuser complies and then goes well beyond those requirements. According to Milton Friedman and the ideals of marketplace responsibility, broad questions about social and environmental corporate responsibilities should be answered by democratically elected governments because that’s the institution we’ve developed to manage our ethical life. Governments should try to succeed in the ethical realm by making good laws; companies should try to succeed in the economic realm by making good profits.

The first part of Douglas’s speech concerned problems with the corporate organization’s structure, and with out-of-control managers: people employed to run a company who promptly forget who their bosses are. The speech’s second part is about what drives life in the business world:

The point is, ladies and gentleman, that greed—for lack of a better word—is good.

Greed is right.

Greed works.

Greed clarifies, cuts through, and captures the essence of the evolutionary spirit.

Greed, in all of its forms—greed for life, for money, for love, knowledge—has marked the upward surge of mankind.

Greed, Douglas says, is an imperfect word for what he’s describing. What words might have been better? What words might advocates of marketplace ethics propose?