In this chapter, we will discuss the federal U.S. Constitution and how it affects businesses. Specifically, you should be able to answer the following questions:

The Constitution is not the first constitution adopted by the original thirteen colonies. During the time of the Revolutionary War against Great Britain, the states were governed by the Articles of ConfederationThe first constitution of the United States of America; it established the union of states.. The articles granted limited authority to a federal government, including the power to wage wars, conduct foreign policy, and resolve issues regarding claims by the states on western lands. Many leading scholars and statesmen at the time, known as Federalists, thought that the articles created a federal government that was too weak to survive. The lack of power to tax, for example, meant that the federal government was frequently near bankruptcy in spite of its repeated requests to the states to put forth more money to the federal government. Larger states resented the structure under the articles, which gave small states an equal vote to larger states. Finally, the articles reserved the power to regulate commerce to the states, meaning each pursued its own trade and tariff policy with other states and with foreign nations. In 1786, work began in a series of conventions to rewrite the articles, resulting in the adoption of the U.S. Constitution in Philadelphia in 1787.

In this chapter we explore the Constitution in depth. We’ll examine how the Constitution sought to rectify the weaknesses in the articles, especially in commerce. We go beyond the meaning of the words and explain how judicial interpretation of the Constitution, while still evolving, has forever changed its original place in U.S. political economy. We’ll explore the first ten amendments to the Constitution, the Bill of RightsThe first ten amendments to the U.S. Constitution., and look at how many of the key civil liberties contained in the Bill of Rights also affect businesses. By the end of the chapter, you should have a solid grasp on why the Constitution remains an enduring document and why it’s important for business professionals to be able to speak on it with authority.

The Articles of Confederation established the United States of America. It provided a central federal government with limited powers, including the power to wage war. The articles ultimately failed because the federal government lacked the power to raise its own taxes or to regulate commerce. In 1787, the Philadelphia Convention adopted a new Constitution to replace the articles.

Have you ever read the Constitution from beginning to end? Look at the text of the Constitution. It’s remarkably short—shorter than many people realize. Historically, it is the shortest and oldest written constitution still in force. Ironically, the Constitution’s brevity may be one of the reasons that it endures to this day, as judicial interpretation has kept its meaning relevant for modern times.

Much of its content deals with the allocation of power among three separate and coequal branches of government. Substantively, much more attention is paid to the limitations on the power given to each of the three branches than to any positive grant of rights. Indeed, while many Americans believe that it is their “constitutional right” to be free, many of those freedoms are actually contained in the Bill of Rights, which are amendments to the Constitution. In contrast, the main body of the Constitution is concerned primarily with structure. In other words, the Constitution is a document of prohibition, outlining what government cannot do as opposed to what government must do.

As a result of this structure, the Constitution is rarely the right place to deal with contemporary political issues, no matter how important. At the state level, many states permit frequent amendments to their constitutions to reflect contemporary public policy, from school funding to gambling to gay marriage. There is often support among many people for constitutional amendments to ban flag burning, permit prayer in school, ban gay marriage, or ban abortion. At the federal level, however, these issues are rarely resolved at the constitutional level. There is a practical bar, of course, given how difficult it is to amend the Constitution. Even if it were easier to amend, however, the Constitution remains very much a document of structure rather than substantive law.

During his confirmation hearings, Chief Justice John Roberts spoke of his role as an umpire calling the balls and strikes and not pitching or batting. If judges are umpires, then the Constitution sets forth the rules of the game. The biggest rule laid down in the Constitution is the separation of powersThe division of enumerated powers of government among separate branches, typically the legislative, executive, and judicial..

Fundamentally, the separation of powers requires that each branch of government play its own role in governing the people. The judicial branch plays a critical role in interpreting the Constitution and outlining the powers of the legislature and executive branches. The interplay between Article I (legislative) and Article II (executive) is no less important. Although more than two centuries have passed since the first Congress and the first president served, the limits of power between these two branches continue to be redefined, especially in the wake of the September 11 terrorist attacks.

Article I of the Constitution establishes the legislative branch through a bicameral legislatureA legislature with two chambers, or houses.. The lower House of Representatives, with frequent elections (every even-numbered year), has 435 members, with representation spread proportionately to a state’s population as determined by a census every decade. The most populous state, California, has fifty-three members, while several states are so small that they have only one representative (Alaska, Delaware, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Vermont, and Wyoming). The House is led by the Speaker of the HouseThe presiding officer in the U.S. House of Representatives., typically from the party that holds the majority in the House. The House is generally thought to represent the most contemporary views of the American public, with its large body of members and frequent elections.

As a check on the majority will, and on the power of larger states, the Senate is a smaller body with one hundred members (two from each state) and with less frequent elections (every six years). The Senate is meant to be a more deliberative body and to ensure a wider level of debate before impassioned legislation is hastily rushed into law. The makeup of the Senate means that citizens from smaller states, representing much fewer people, can often frustrate the will of the majority of Americans. The Constitution places the power to legislate with both chambers, but the House retains the exclusive right to originate bills raising revenue (taxation), while the Senate maintains the exclusive right to provide advice and consent to the president, where advice and consent are required. Additionally, while the House retains the right to impeachTo formally accuse an elected official of misconduct. officials for “high crimes and misdemeanors,” the Senate tries such impeached officials.

Article II of the Constitution establishes the executive branch of government. While the Constitution was being drafted, the delegates knew that they wanted George Washington to be president. Washington was in retirement in Mount Vernon at the time, after successfully leading the colonies in the Revolutionary War. Since the delegates knew Washington would be president, they spent remarkably little time in writing Article II, which is very short. Washington was elected to both his first and second terms with 100 percent of the Electoral College vote, something no other president has since done. While Article II sets forth some of the mechanisms for becoming president—and is the only place in the Constitution that prescribes a specific oath of office—when the Constitution was drafted, little was known about what the president’s role would be.

Article II grants the president an almost total power over foreign affairs, including the power to make treaties and appoint ambassadors. He is commander-in-chief of the armed forces. The president is also responsible for executing, or enforcing, the laws of the country. While Congress can pass any legislation it wants to, ultimately legislation is meaningless unless there are sanctions for violating the law. Through the prosecutorial and police functions, the president ensures that the will of the people, as expressed through Congress, is carried out.

The Constitution’s deliberate ambiguity on the powers of the president left much room for debate on how strong the executive branch should be. After the September 11 attacks, many in the George W. Bush administration argued for a strong unitary executiveA theory in constitutional law that the president controls the entire executive branch, totally and completely. theory. Bush administration lawyers reasoned that only a strong executive could effectively wage war with Al-Qaeda. Under a congressional authorization, the administration embarked on a program to capture and kill terrorists around the world and to gather as much information about terrorist activities as possible. Many in Congress believed, however, that the executive branch overstepped its authority in pursuing these goals, leaving Congress behind.

For example, to collect intelligence on suspected terrorists in the United States, Congress passed a law, the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, in 1978. FISA, as the law is known, requires federal law enforcement officials to seek a search warrant from a secret court before carrying out surveillance or wiretapping. The Bush administration routinely carried out surveillance on persons in the United States without this judicial oversight, arguing that it was part of the unitary executive theory to do so. In another program, the Bush administration allegedly captured suspected terrorists abroad and moved them to secret prisons outside the jurisdiction of the United States for interrogation, a practice known as extraordinary renditionThe capture and transfer of suspected criminals from one country to another for interrogation.. In late 2009, an Italian court convicted twenty-three American officials, including members of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), of extraordinary rendition in the case of a Muslim cleric kidnapped from Milan. The officials were convicted in their absence and have not been extradited to Italy. Extraordinary rendition is likely illegal under U.S. and international law, but lawsuits attempting to find out more information about the program have been thwarted by the executive branch’s claim of the state secretsThe doctrine that certain information on national security is so sensitive that it cannot be disclosed in court. doctrine.

Congress and the president have also clashed over the treatment of suspected terrorists. Article I, Section 9 of the Constitution states that “The Privilege of the Writ of Habeas CorpusThe right to seek release from unlawful detention by petitioning a neutral judge. shall not be suspended, unless when in Cases of Rebellion or Invasion the public Safety may require it.” The right of habeas corpus is a fundamentally important right, appearing first in the Magna Carta and considered so important by Constitutional delegates that it was inserted into the text of the Constitution itself, not in the Bill of Rights. When the Bush administration began imprisoning suspected terrorists at the military base in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, the administration took a series of unprecedented positions on the legal status of those detainees, including the position that the detainees did not have the right to seek habeas relief. Federal courts, including the Supreme Court, gradually overturned most of these positions, and the detainees are now being tried by either military tribunals or civilian courts.

Another controversial position adopted by the administration was on the use of enhanced, or aggressive, interrogation methods. Critics claimed these techniques amounted to torture (which is banned by U.S. law as passed by Congress) and may be unconstitutional under the Eighth Amendment, which prohibits cruel or unusual punishment.

Another aspect of the separation of powers that is less obvious is the separation of power between the federal and state governments, known as federalismThe division and sharing of power between state and federal governments.. You already know that state and federal governments sometimes share power and that the rules of subject matter jurisdiction determine which legal system has jurisdiction over a particular matter or controversy. In some areas, such as family or property law, the states have near exclusive jurisdiction. In other areas, such as negotiating treaties with foreign countries or operating airports and licensing airlines, the federal government has near exclusive authority. In the middle, however, is a large area of subject matter where both state and federal governments may potentially have jurisdiction. What happens if state and federal laws exist on the same subject matter, or worse, what happens if they directly contradict each other?

Legal rules of preemptionThe doctrine that permits federal law to trump, and render unenforceable, conflicting state laws. seek to provide an answer to these questions. Under the Constitution’s Supremacy Clause (Article VI, Section 2), the Constitution and federal laws and treaties are the “supreme law of the land” and judges in every state “shall be bound” by those laws. Let’s say, for example, that Congress sets the minimum wage at $7.25 an hour. A state that passes a law making the minimum wage lower than that would immediately see the law challenged in federal court as unconstitutional under preemption and Supremacy Clause principles, and the state law would be overturned.

http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=113924395

Under the federal Food and Drug Act, marijuana is classified as a Schedule I drug under the Controlled Substances Act, meaning it is restricted just like cocaine or heroin. Fourteen states have passed laws that permit marijuana to be grown, sold, and used for medicinal purposes, such as treating nausea and stimulating hunger in cancer patients. The federal government aggressively prosecuted medicinal use of marijuana, and in 2005 the Supreme Court ruled that the federal law trumps state laws,Gonzalez v. Raich, 545 U.S. 1 (2005). meaning that local growers could be arrested and prosecuted under federal law even if what they were doing was perfectly legal and authorized under state law. In 2009 the Obama administration announced a change in policy. Listen to this National Public Radio story about what this change means for the medicinal use of marijuana in the states.

When there is no direct conflict between state and federal law, then the rules of preemption state that courts must look to whether or not Congress intended to preempt the state law when it passed the federal statute. If there is no clear statement by Congress that it wishes to preempt state law, or if it is unclear what Congress meant to do, then the state law will survive if possible (i.e., there is a presumption against preemption). Even if there is no statement by Congress on preemption, however, if Congress so completely regulates a particular subject area that there is “no room” left for states to regulate, then preemption exists. For example, after September 11, Michigan passed a law requiring student pilots in Michigan to pass a Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) background check. The Federal Aviation Administration, which sets forth pilot qualifications and licensing, has no such requirement, and since the federal government regulates the aviation industry completely (from airports to pilots to airlines to training standards), Michigan’s law is preempted.

http://www.nhtsa.dot.gov/cars/rules/import/fmvss/index.html

Sometimes it’s not clear whether or not a state law is preempted, and the courts must undertake a searching inquiry to determine congressional intent. In Geier v. Honda,Geier v. American Honda Motor Company, 529 U.S. 861 (2000). for example, a teenager filed a tort lawsuit against Honda for injuries she suffered during a car accident. Her lawsuit claimed that her 1987 Honda Accord was defective because it didn’t have any airbags. Airbag technology, which existed at the time but was used primarily in expensive luxury cars, would have minimized her injuries. If she had won her state lawsuit in the District of Columbia, then in effect all 1987 Honda Accords sold in the District of Columbia would have to be equipped with airbags to avoid tort liability. Honda’s defense was preemption. Under a federal regulatory scheme known as the Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards (FMVSS), the federal government sets forth safety standards that cars must meet to be sold in the United States. FMVSS 208 sets the standard for seat belts, and in 1987 manufacturers were required to install either airbags or passive (motorized) seat belts. A rule that required manufacturers to install airbags exclusively would directly contradict FMVSS 208, so the Supreme Court ruled that FMVSS preempted any state attempts to regulate motor vehicle safety standards.

When the Supreme Court found preemption in the Honda case, many in the business community wondered if a new era of preemption might have arrived. Federal regulation would in effect provide a shield against liability lawsuits. These hopes were short lived, as the Supreme Court continues to hold a presumption against preemption. The drug industry, in particular, would like preemption to end tort litigation.

http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=101465350

Wyeth Pharmaceuticals manufacturers an antinausea drug called Phenergan, which was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1955. Under federal law, the FDA must approve the wording on labels and documentation accompanying regulated drugs. The FDA-approved label contained warnings against “intra-arterial” injection, which carried the risk of irreversible gangrene. The plaintiff in the case, Vermont musician Diana Levine, went to a clinic for treatment and ended up losing her arm when Phenergan was incorrectly administered to her. She sued Wyeth, arguing that the warning label on the drug didn’t prohibit the type of injection that led to her injuries. A jury awarded her more than six million dollars in damages. On appeal to the Supreme Court, Wyeth argued that since the FDA approved the label, lawsuits arguing that the label was inadequate were preempted. The Supreme Court examined the history of the Food and Drug Act and ruled for Diana Levine, holding that when Congress wrote the law, it never meant to preempt state laws. In fact, the Supreme Court found that Congress meant for state lawsuits to work alongside the Food and Drug Act to ensure drug safety for consumers.

The Constitution is mainly a structural document, setting forth the allocation of power among the three branches of government and the limitations on that power. It is concerned mainly with what the government cannot do, as opposed to what the government must do. At the federal level, constitutional amendments are rarely used to carry out social policy. Article I of the Constitution establishes a bicameral legislature, with a House of Representatives and a smaller, more deliberative Senate. Both chambers must agree before legislation can be passed. Article II of the Constitution establishes the executive power in the president, who must execute the laws passed by Congress. The balance of power between Congress and the president is subject to much interpretation and change throughout history, including the post–September 11 era. Power is also divided between state and federal governments under federalism. The Supremacy Clause states that when there is a conflict between state and federal law, federal law wins. If there is no direct conflict, the state law survives unless Congress expressly preempts state law.

http://topics.law.cornell.edu/constitution/articlei#section8

Members of the Constitutional Convention were divided about how powerful the new central government should be. To avoid the rise of tyrannical government, the Constitution carefully grants certain powers to Congress, reserving all other powers to the states. These powers are listed in Article I, Section 8. Look at this section in Note 5.25 "Hyperlink: The Powers of Congress" and notice how detailed these powers are.

The list begins with monetary matters, an issue of great concern at the time because the prior government was bankrupt and states regulated their own money supply. The Congress therefore has the power to borrow money, lay and collect taxes, regulate commerce (the Commerce ClauseThe power granted to Congress to regulate foreign and domestic commerce.), establish a uniform law on bankruptcy and naturalizationThe process and procedure to become a citizen., make money (currency) and establish its value, punish the counterfeiting of U.S. money, and establish a uniform system of weights and measures. The list then moves on to aspirational ideals for the young new country to strive toward. Congress has the power to establish post offices and post roads and to protect intellectual property in copyrights and patents. Next, the list turns to Congress’s adjudicative powers: to create lower courts under the Supreme Court created in Article III and to define crimes committed on the “high seas” and against the “law of nations.” Congress is also given fiscal responsibility over the armed forces and navy (note there is, of course, no mention of an air force) and the power to provide oversight to the militia. Then, to help Congress with carrying out these powers, Article I, Section 8 provides that the states may cede to Congress a district, not to exceed ten square miles, that will become the seat of government, and to exercise exclusive legislative authority over this district.

The scope of power granted under Article I, Section 8 is the subject of much debate among legal scholars. The clause granting Congress the power to regulate commerce is particularly troublesome. There is very little debate about the power of Congress to regulate foreign trade. This power is explicit, total, and exclusive. If Congress wanted to ban all imports and exports into and out of the United States, for example, it could legitimately do so. Indeed, Congress routinely uses economic trade sanctions against “rogue” nations such as Cuba and North Korea as a means of economic warfare to try to bring about regime change. Even in the case of friendly allies such as Canada, Mexico, and the European Union, Congress routinely engages in trade regulations that restrict or distort foreign trade. Since this power is exclusive to Congress, state attempts to regulate foreign commerce are invalid. Oregon, for example, cannot ban Oregon companies from exporting to Mexico or establish a free trade zone with duty-free imports with China.

There is more disagreement about Congress’s power to regulate domestic commerce. Notice how Article I, Section 8 is structured. Many scholars believe that this list is complete and exhaustive, since it lists all the powers the Founding Fathers wanted to give Congress at the time. The idea, they argue, was to create powerful and limited government, leaving the states room to govern in all other areas. As evidence, these scholars point to the structure of the list and the high level of detail provided (such as specific crimes to be made punishable and the square mile limitation for the seat of government). Other scholars believe that the list should be interpreted more broadly and that the language granting Congress the power to “make all laws necessary and proper” to carry out the enumerated powers demonstrates the Founding Fathers’ desire for a more flexible interpretation, to allow Congress the power to react to needs and challenges not foreseeable at the time the clause was drafted.

In the early part of the country’s history, the first view held firm sway, and together courts and Congress carefully observed the constitutional limits to the growth of federal government power. If you consider our modern federal government, however, it’s obvious that the second view is now more prevalent. Today, the federal government does a lot more than what is enumerated on the list in Article I, Section 8. From regulating educational standards, to defining clean air and water, to outlawing workplace discrimination, to licensing portions of the electromagnetic spectrum for cell phone and digital television providers to use, it’s clear that if a member of the Constitutional Convention were to travel forward in time, he would be shocked at both the pace of progress and the size and power of the federal government. How did our country’s view of congressional power evolve over time?

The answer can be traced to the Great Depression. In response to unprecedented economic distress, President Roosevelt sought to redefine the very nature of the employer/employee relationship. He, along with Congress, enacted legislation that established a minimum hourly wage, set maximum weekly working hours, established workplace safety rules, outlawed child labor, and provided for a safety net to protect older and disabled workers. These laws initially ran into stiff opposition at the Supreme Court. The justices at the time clung to a more formalistic reading of Article I, Section 8 and saw the employer/employee relationship as one governed by freedom of contract. In this view, if a worker wanted to work and an employer was willing to provide that work, then the government should not interfere with that contract. Thus, early portions of the New Deal were struck down as unconstitutional under the Commerce Clause.

After President Roosevelt proposed his court-packing plan, leading one of the swing votes on the Supreme Court to change his vote to begin upholding the New Deal, the barriers surrounding the interpretation of the Commerce Clause came crashing down. Courts have now adopted a very flexible reading of the Commerce Clause. As long as Congress makes reasonable findings that a certain activity has some sort of effect on interstate commerce, Congress can regulate that activity.

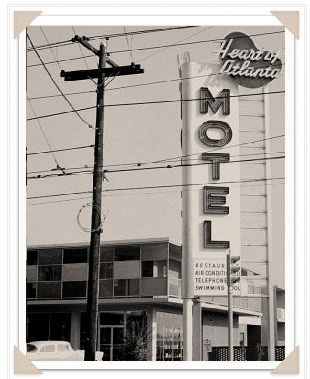

This broad interpretation of the Commerce Clause has been challenged repeatedly. In 1964, for example, Congress passed a broad and sweeping Civil Rights Act, prohibiting discrimination against citizens on the basis of race, color, national origin, and sex. Congress relied on its power under the Commerce Clause to pass this legislation. That same year, the Heart of Atlanta Motel in Georgia (Figure 5.3 "Heart of Atlanta Motel") filed a federal lawsuit seeking to overturn the Civil Rights Act as unconstitutional, arguing that Congress lacked the authority under the Commerce Clause to pass the law. The Supreme Court held the law to be constitutional, finding that since 75 percent of the motel’s clients came from out of state and since the motel was located near Interstates 75 and 85, the business had an “effect” on interstate commerce.Heart of Atlanta Motel v. United States, 379 U.S. 241 (1964). Subsequent civil rights legislation, including the important Americans with Disabilities Act, is also grounded in congressional authority to regulate interstate commerce.

Figure 5.3 Heart of Atlanta Motel

Source: Photo courtesy of Georgia State University, Special Collections of the University Library, http://tarlton.law.utexas.edu/clark/heart_long.html.

In the late 1990s, several curious decisions by the conservative wing of the Supreme Court led some observers to wonder if the days of virtually unfettered authority by Congress to regulate under the Commerce Clause were coming to an end. Judicial conservatives, especially the late Chief Justice Rehnquist, have always been somewhat uncomfortable with the broad reading of the Commerce Clause, worried that it has led to a runaway federal government many times bigger than what the Founding Fathers intended. In a 1995 case, the Supreme Court held that the 1990 Gun-Free School Zones Act was unconstitutional. The law prohibited the possession of weapons in schools and was based on a congressional finding that possession of firearms in educational settings would lead to violent crime, which in turn affects general economic conditions by causing damage and raising insurance costs and by limiting travel to and through unsafe areas. Students intimidated by a violent educational setting would also be affected, learning less and leading to a weaker educational system and economy. By a 5–4 margin, the Supreme Court found these arguments unpersuasive and overturned the law, holding that Congress lacked authority under the Commerce Clause to regulate the carrying of handguns into schools.United States v. Lopez, 514 U.S. 549 (1995). Then, five years later, the Supreme Court overturned a portion of the 1994 Violence Against Women Act, which gave a woman the right to sue her attacker in federal court for civil damages, holding that the effects of violence against women were too “attenuated” to be valid under the Commerce Clause.United States v. Morris, 529 U.S. 598 (2000). Any expected revolution in the scope of Congress’s authority failed to materialize, however, and these two cases are probably aberrations rather than predictors of where the Court is heading on this topic.

While the Constitution limits the federal government’s powers to those enumerated in Article I, Section 8, the states also have broad lawmaking authority. These powers stem from the states’ police powerThe general power of states to regulate for the health, safety, and general welfare of the public., which permits states to regulate broadly to protect and promote the public order, health, safety, morals, and general welfare. You’ve probably experienced this yourself. Different states have different speed limits, for example. Some states permit the sale of alcohol on Sundays, while others prohibit it. Some states permit casino gambling, while others do not. A few states permit same-sex marriage, while many do not. Some states prohibit smoking in bars and restaurants, including North Carolina, home to the nation’s tobacco industry. In California, an attempt to rein in obesity resulted in a state law to require calorie counts on restaurant menus and a ban on the use of trans fats. In Texas, teenagers must have parental permission to use tanning beds at a salon. Massachusetts bans dog racing. Many states are implementing bans on texting while driving.

http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=5160904

In 1994 Oregon voters approved the country’s first physician-assisted suicide law, the Oregon Death with Dignity Act. The law permits certain patients to voluntarily hasten death by taking a lethal dose of prescription medication. To meet the law’s requirements, the patient must be terminally ill with less than six months to live, must be informed and voluntarily request the medication, must be able to consume the medication by himself or herself, must be referred to counseling, and must have the terminal diagnosis confirmed by a second doctor. Many patients, fearing a painful or torturous natural death, obtain the medication and never take it, but some do. In 2001 Attorney General John Ashcroft issued a rule interpreting the federal Controlled Substances Act as prohibiting any physician from prescribing medication under the Death with Dignity Act, subjecting any doctor who did so to federal prosecution. In a 6–3 decision, the Supreme Court decided that the Controlled Substances Act did not grant the attorney general the authority to override a state standard for regulating medicine.Gonzalez v. Oregon, 546 U.S. 243 (2006). In doing so, the Court held that the state police power is entitled to greater deference, in this case, than Congress’s powers under the Commerce Clause. Listen to the National Public Radio story for one physician’s account of how the Death with Dignity Act has affected his practice.

The Oregon Death with Dignity Act case illustrates how a state, in exercising its police power, can actually grant more civil rights to its citizens than the federal government does or wishes to. Similarly, states that have legalized same-sex marriage have done so under their police powers, which is permissible as long as the exercise of police power does not violate the federal Constitution. Generally, this means the state legislation must be reasonable and applied fairly rather than arbitrarily. Additionally, a critical limitation on the state police power is that it cannot interfere with Congress’s power to regulate interstate commerce. This concept is known as the dormant commerce clauseThe concept that restricts states from placing an undue burden on interstate commerce. because it restricts the states’ abilities to regulate commerce, rather than the federal government’s.

A state law that discriminates against out-of-state commerce, or places an undue burdenA constitutional test created by the Supreme Court to determine a law’s validity. on interstate commerce, would violate the dormant commerce clause. For example, if a state required out-of-state corporations to pay a higher tax or fee than an in-state corporation, that would be unconstitutional. A state that required health and safety inspections of out-of-state, but not in-state, produce or goods would be unconstitutional. In 2005 the Supreme Court held that state restrictions prohibiting out-of-state wineries from selling directly to consumers in-state was unconstitutional.Granholm v. Heald, 544 U.S. 460 (2005). Federal courts have repeatedly held that state attempts to regulate Internet content (typically to prevent pornography) are unduly burdensome on interstate commerce and therefore unconstitutional. Note, however, that this prohibition against out-of-state discrimination does not prevent a state from exercising its police power to protect state citizens, as long as the power is exercised evenly and equally. If a state wanted to weigh trucks on highways to ensure they did not exceed maximum weight rules, for example, that action would be permissible even if the trucks came from out of state, as long as the requirement applied equally to all trucks on that state’s highways.

In addition to the power to regulate commerce, the Constitution places two critical powers with Congress: the taxing powerThe power granted to Congress to raise revenue through taxation. and the power to spend the taxes it collects. The taxing power is a broad one, and the Supreme Court has not overturned a tax passed by Congress in nearly a century. As long as the tax bears some reasonable relationship to generating revenue, the tax is valid.

States are also permitted to tax, but only if the activity taxed has a nexusA sufficient connection to justify state taxation. to the state. A transaction (such as a sale) that takes place inside the state would create a nexus for sales tax to attach. Working typically creates a nexus for state or local income tax to apply, and owning real property creates a nexus for real estate tax to apply. What happens, however, if a state’s citizen purchases goods from a seller out of state? Traditionally, buyers do not pay sales tax to the government directly—rather, they pay the sales tax to the seller, who collects the tax on behalf of the government and turns it over to the government at regular intervals. In the past, mail-order catalog sellers from out of state would not collect sales tax in states where they don’t have a physical presence. As the popularity of e-commerce has skyrocketed, more and more states are reexamining how to tax transactions from out-of-state sellers by compelling those sellers to collect the applicable sales tax. Some states are so desperate they are starting to look for a nexus anywhere they can. In New York, for example, the legislature passed a law requiring Amazon.com to collect sales tax from New York residents based on the presence of New York citizens who link to Amazon’s Web site in turn for a commission generated by those links.

Congress also has the power to “pay the debts and provide for the common defense and general welfare.” This spending powerCongress’s power to spend public revenue to meet broad public objectives. is considered very broad. Courts have interpreted this power to mean that Congress can spend money not only to carry out its powers under Article I, Section 8 but also to promote any other objective, as long as it does not violate the Constitution or Bill of Rights. For example, in 1984 Congress passed the National Minimum Drinking Age Act, which required states to adopt a minimum age of twenty-one for the purchase and possession of alcohol. If a state did not adopt the age-twenty-one requirement, Congress would withhold federal highway funds from that state to repair and build new roads. One by one, states began adopting age twenty-one as the minimum drinking age, even though the age requirement would typically be a matter of state police power. In a challenge by South Dakota, which wanted to keep nineteen as the minimum drinking age, the Supreme Court upheld Congress’s use of withholding funds to force the states to raise the minimum drinking age.South Dakota v. Dole, 483 U.S. 203 (1987). Congress has used the spending power to coerce states to adopt a fifty-five-mile-per-hour speed limit (rescinded by the Clinton administration) and to lower the driving under the influence (DUI) blood alcohol level limit from 0.10 in most states to 0.08.

Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution grants certain specific powers to Congress. The power to regulate commerce is one of these powers, and the power of foreign commerce is explicit, total, and exclusive. During the Great Depression, the Supreme Court greatly expanded the interpretation of Congress’s ability to regulate domestic interstate commerce, and this expansion led to congressional authority to regulate virtually all human activity within the United States, with very few limited exceptions. This authority extends to civil rights, where Congress has passed several key pieces of legislation, including the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Americans with Disabilities Act, under the Commerce Clause. Attempts by judicial conservatives to circumscribe the power of the Commerce Clause appear to have failed for now. Unlike the federal government, states have broad police powers to regulate for the health, safety, and moral well-being of their citizens. The exercise of these police powers cannot violate the federal Constitution and, importantly, cannot violate the dormant commerce clause by discriminating against or placing an undue burden on interstate commerce. The power to tax is broad, and as long as a tax bears a reasonable relationship to raising revenue, the tax is upheld as constitutional. The power to spend is similarly broad, and Congress can spend funds to achieve broad objectives beyond its enumerated powers.

The ink on the Constitution was barely dry when the first Congress began turning its attention to amending it. During the debate surrounding the Constitution, there was much discussion about whether or not an explicit protection of civil liberty was necessary. Some believed that the British common-law system implicitly protected civil liberties, so a written declaration of rights wasn’t necessary. Others believed that the Constitution created a strong federal government and that a written declaration of rights was therefore critically necessary. In 1789, the same year the Constitution went into effect, Congress proposed ten amendments to the Constitution, a package that became known as the Bill of RightsThe first ten amendments to the U.S. Constitution.. Within two years, the Bill of Rights had garnered the necessary votes to become law.

When we speak of civil liberties protected in the Constitution, we often think of how these liberties apply to people. Although the Constitution does not contain the word “corporation,” corporations have some characteristics of being a “person,” so various courts have held that several of these civil rights also apply to business entities. In this section we’ll take a closer look at how these rights apply to businesses. In particular, we’ll examine the First, Fifth, and Fourteenth amendments.

Before we begin, it’s worth making some observations about civil liberties generally. First, there are no absolute rights, in spite of the wording of any specific amendment. For example, the First Amendment states that “Congress shall make no law abridging the freedom of speech.” In fact, there are many laws that limit the freedom of speech. You aren’t allowed to libel or slander someone, for example, or incite a crowd into a riot. Instead of absolute rights, courts have to constantly balance competing interests in deciding where the limits of our rights lie. The right of the public to know information about the lives of politicians and other high-profile figures, for example, must often be balanced by the right those citizens have to their own privacy.

Second, it’s fair to say that while the Constitution sets up a system of government based on principles of representative democracy, the Bill of Rights exists to protect the minority, not the majority. The vast majority of Americans will go through life without ever having their constitutional rights trampled on. It is for the very small minority of Americans that find themselves victims of constitutional violations that we find the greatest strength of the Bill of Rights. For this reason, many issues raised by civil liberties generally rise above the political process, where the majority generally prevails. For example, public opinion polls show that well over 95 percent of Americans feel that burning the American flag should be illegal. When such an overwhelming majority agrees on something, in a democracy the majority should prevail. In our democracy, however, the Supreme Court has stepped in and decided that the First Amendment will protect the very tiny percentage of the American population that wishes to burn the flag as a display of political opposition. Additionally, it’s important to note that the only reason those of us in the majority know where the boundaries of our civil liberties lie is because of that tiny minority. If Americans weren’t willing to test the boundaries by burning the flag or joining the Communist Party or refusing to take loyalty oaths or refusing to send their Amish children to public schools, then our civil liberties would remain theoretical ideals rather than concrete rights. Finally, note that other than the right to vote, the civil liberties protected by the Constitution extend to all persons physically on U.S. soil, not just citizens or legal immigrants. Persons visiting the United States temporarily, such as tourists and students, as well as undocumented aliens, are all entitled to the full protections of the U.S. Constitution while subject to U.S. law.

Third, the extent of our civil liberties protections vary from time to time. Society evolves with progress and challenges, and with that evolution, different needs arise in the realm of civil liberties. The Founding Fathers could not contemplate a digital world where an act of defamation on Facebook can spread to millions of people in a matter of hours, or imagine a society as pluralistic and diverse as ours has become. One constitutional amendment, the Eighth, illustrates how time shifts the meaning and application of civil liberty. The Eighth Amendment prohibits “cruel and unusual” punishment. The Supreme Court, in defining what “cruel and unusual” is, looks to “evolving standards of decency” in making the determination—in other words, what is cruel and unusual today may have been normal in years past.

Finally, major portions of the Bill of Rights apply equally to the states as they do the federal government. When adopted, the amendments were meant to restrict the federal government only (for example, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion.”). States were not similarly restricted, and many states did in fact establish official state churches in the early days of the United States. After the Civil War, the Constitution was amended to include the Fourteenth Amendment, which prevents any state from depriving citizens of their rights without “due process of law.” Gradually, throughout the twentieth century, the Supreme Court developed a doctrine called incorporationThe doctrine by which certain provisions of the Bill of Rights are applied against the states., by which the limitations on government behavior in the Bill of Rights were extended to apply to the states as well. While many portions of the Bill of Rights apply to the states, not all of it does. There is no requirement, for example, that states use a grand jury system to indict criminals. There is also no requirement that states provide juries in civil trials.

http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=128182208

In 2008 the Supreme Court handed down a major victory for gun owners and gun rights advocates by declaring that a ban on handguns in the District of Columbia was unconstitutional under the Second Amendment, which the Court held protected an individual’s right to possess a firearm in private homes in Washington, DC, and other federal territories.District of Columbia v. Heller, 554 U.S. ___ (2008), http://www.law.cornell.edu/supct/html/07-290.ZS.html (accessed October 2, 2010). Soon after the case was decided, several lawsuits were filed across the nation, challenging similar bans on handguns in various states. In 2010 the Supreme Court decided that the Second Amendment is indeed incorporated against the states, meaning that state laws banning the possession of handguns in private homes are unconstitutional.McDonald v. Chicago, 561 U.S. ___ (2010), http://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/09pdf/08-1521.pdf (accessed October 2, 2010).

We turn our attention first to the First Amendment. The First Amendment contains several important clauses pertaining to speech and religion. The two different clauses on religion are designed to be almost always in conflict with each other. On the one hand, the First Amendment prohibits the government from establishing any religion—this is called the Establishment ClauseThe section of the First Amendment prohibiting government from establishing a religion.. On the other hand, the First Amendment prohibits the government from restricting the free exercise of religion—this is called the Free Exercise ClauseThe section of the First Amendment prohibiting government from preventing the free exercise of religion.. The conflict arises when some segments of society believe that the Free Exercise Clause means that they can practice their religion freely and openly, such as in a public school or city hall. Those who believe in what Thomas Jefferson called a “wall of separationThe phrase coined by Thomas Jefferson (in a letter to the Danbury Baptist Association after it congratulated him on his election) to describe the Establishment Clause.” between church and state, on the other hand, believe that the Free Exercise Clause must be subservient to the Establishment Clause, which would strictly prohibit such public displays of religious life.

As is often true in Bill of Rights cases, courts have had to fashion a test to draw the lines between these two competing visions of the Establishment and Free Exercise clauses. Generally speaking, the use of public funds for religious purposes and the public display of religious life are generally acceptable as long as the primary motivation is not to advance a specific religion. A city that wishes to display a Christmas tree or nativity scene, for example, would be permitted to do so as part of a general holiday-themed cultural display that also included a menorah and Rudolph, while a public high school that wished to have a public prayer before a football game would be prohibited. Several evangelical Christian groups have campaigned hard to de-emphasize teaching evolution in public high schools, replacing it with an alternative theory called intelligent designAn alternative theory on the origin of life that states the universe is too complex to be explained by science alone., which states that the universe is so complex that it is impossible to be explained by random nature and, therefore, an intelligent entity designed it. In one high-profile trial involving a lawsuit against a school board for adopting intelligent design, a Republican-appointed federal judge found intelligent design to be a thin disguise for the teaching of Bible-based creationism, a violation of the Establishment Clause.Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District, 400 F. Supp. 2d 707 (M.D. Pa. 2005). On the other hand, the Supreme Court has found that the use of public funds to display the Ten Commandments on public lands such as parks is not automatically an Establishment Clause violation, depending on the context in which the monument or statue was erected.Van Orden v. Perry, 545 U.S. 677 (2005).

The First Amendment also protects the right to freedom of speech. While many nations believe in the right of citizens to think and speak freely, the United States is fairly unique in enshrining those principles into constitutional law. As is true in most Bill of Rights cases, the cases that test the limits of the First Amendment tend to be ones that involve the most unpopular, even heinous, speech. For example, after World War II many European nations outlawed the Nazi Party along with any Nazi propaganda material, as well as neofascist ideology. As a result, many pro-Nazi and white supremacist Web sites, books, catalogs, and music are hosted in the United States, where the First Amendment protects even hateful speech.

Not all speech is protected by the First Amendment; the type of speech very much drives the level of protection afforded it under the First Amendment. Courts generally recognize political speechAny speech dealing with politics or political figures. as speech most deserving of protection. Political dissent, displeasure with the government, forced loyalty oaths, restrictions on party membership, and even speech advocating the overthrow of government, all deserve extraordinary protection under the First Amendment. Political speech isn’t always written or uttered—it can sometimes take place through symbolic speechSpeech that is not uttered or printed but displayed or performed instead.. The Supreme Court has held, for example, that burning the U.S. flag as a form of protest against U.S. government policy is symbolic speech, and therefore attempts to criminalize flag burning are unconstitutional restrictions on political speech.Texas v. Johnson, 491 U.S. 397 (1989).

On the other end of the spectrum is speech that deserves no protection under the First Amendment at all, such as speech that incites a panic (yelling “Fire” in a crowded theater when there is no fire, for example). DefamationFalse statements that impugn or damage someone’s character or credibility. is another type of speech that falls into this category, and both libelWritten forms of defamation. and slanderSpoken forms of defamation. are actionable torts. ObsceneA legal standard that, if met, means the work in question has no protection under the First Amendment. speech is also not subject to any protection under the First Amendment. Defining what is obscene has always vexed courts. The best test courts have developed is called the Miller test.Miller v. California, 413 U.S. 15 (1973). Under the Miller test, material is considered obscene if when applying contemporary community standards, the work, taken as a whole, appeals to a prurient interest in sex; portrays sexual conduct as specifically defined by applicable state law; and lacks serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value. It’s important to keep in mind, however, that even obscene and defamatory speech is subject to the doctrine of prior restraintA doctrine that prevents the government from restricting or punishing speech before it is uttered or published, in case the speaker changes his or her mind before proceeding.. Attempts to shut down the speech before it is uttered are considered unconstitutional.

http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=10741235

Although the First Amendment generally prevents the U.S. government from engaging in censorship, an exception exists for broadcast radio and television. Unlike cable and satellite programming, which requires viewers and listeners to “opt in” with a paid subscription to access content, broadcast radio and television use the public airwaves to carry transmissions that are readily accessible for free by anyone with a television or a radio. In 1973, in a case involving comedian George Carlin’s “Dirty Words” monologue, the Supreme Court held that although the monologue wasn’t obscene, the government (through the Federal Communications Commission, or FCC) could nonetheless regulate indecent material when vulnerable listeners, such as children, may be listening.F.C.C. v. Pacifica, 438 U.S. 726 (1978). Under this authority, the FCC enforces the “fleeting expletives” rule, which fines broadcasters for airing even momentary exclamations of profanity during live broadcasts. In 2010, after several rounds of litigation, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals held the FCC’s policy was unconstitutionally vague.

One area of First Amendment law that remains unsettled is what rights corporations have to speak, also known as commercial speechSpeech made by nonhuman entities.. In the early part of the twentieth century, the Supreme Court found that corporations had virtually no protection under the First Amendment. This view gradually evolved as the role and influence of companies grew. Today, corporations engage not just in purely commercial speech such as product advertising but also in matters of public policy, from globalization to human rights to environmental protection and global warming. In 2002 it looked like the Supreme Court would finally issue some guidance on this issue.Nike v. Kasky, 539 U.S. 654 (2003). In California, Nike Inc. was under fire from labor activists for allegedly engaging in sweatshop conditions in its foreign factories, including hiring child labor. In response to these allegations, Nike issued a series of press releases and denials, the “speech” in this case. Several activists filed lawsuits against Nike, claiming that these press releases and denials constituted false advertising by a company, which is against California law. Nike’s defense was that the press releases were more like political speech and were therefore protected by the First Amendment. Nike lost the argument in California state courts, and when the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to hear the case, the parties settled before the case could proceed any further.

In early 2010, however, the Supreme Court handed down another important decision on the rights of corporations to speak.Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, 558 U.S. ___ (2010), http://www.fec.gov/ law/litigation/cu_sc08_opinion.pdf (accessed October 2, 2010). In striking down federal and twenty-two state restrictions on corporate spending on political campaigns, the Supreme Court held that corporations are persons and therefore entitled to engage in political speech. Since corporations are unable to literally “speak,” they speak through spending money, and thus restrictions on how corporations may spend money during political campaigns are unconstitutional. The four dissenting justices worried about the implications of this ruling. If corporations aren’t allowed to vote, then why should corporations be allowed to spend freely to drown out the voices of real voters, who have no hopes of matching corporate spending on issue advertisements? Similarly, foreign persons have the same rights as U.S. citizens in making speeches on U.S. soil. If corporations are persons for purposes of speech, then it stands to reason that foreign corporations operating in the United States are entitled to the same protections and can also spend freely to influence U.S. elections. The implications of this ruling will likely be felt for many years to come.

Not all protected speech is protected all the time in all places. The government is permitted to place reasonable time, place, and manner restrictions on speech to maintain important governmental functions. These restrictions are generally upheld if they further an important or substantial governmental interest, they are unrelated to the suppression of free expression (in other words, are content neutral), and any restriction on First Amendment freedoms is no greater than that necessary to further governmental interests (the restriction is not overbreadthA law that covers legal conduct as well as illegal conduct.). Thus, for example, courts have upheld restrictions on posting signs on city-owned utility poles and picketing or protest permit requirements. On the other hand, when Congress tried to make it illegal for commercial Web sites to allow minors to access “harmful” content on the Internet in the Child Online Protection Act (COPA), the Supreme Court held the Act unconstitutional because of the overbreadth doctrine.ACLU v. Ashcroft, 535 U.S. 564 (2002). The Court found there were less restrictive alternatives than the Act, such as blocking and filtering software, and therefore the burdens placed by COPA on the First Amendment, by sweeping both legal as well as illegal behavior, were too heavy to be constitutional.

Figure 5.4 Joseph Frederick and Bong Hits 4 Jesus

Source: Photo courtesy of Clay Good / Zuma Press, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Bh4j.jpg.

Does this doctrine permit school officials to curb the free speech rights of high school students, who otherwise have rights outside of school hours? In 2002 an eighteen-year-old high school senior was suspended after he (with help from some friends) unfurled a banner during the Olympic torch relay through his town. The student, Joseph Frederick, was not in school that day and was standing across the street from the school when he unfurled the banner (Figure 5.4 "Joseph Frederick and Bong Hits 4 Jesus"). When asked later what the banner meant, Frederick replied that it was a nonsensical phrase he saw on a sticker while snowboarding. Frederick sued his high school principal for violating his First Amendment rights and won in the lower courts. On appeal, however, by a 5–4 decision the Supreme Court held that the school, which has a zero-tolerance policy on drug use, could restrict a student’s prodrug message even in these circumstances.Morse v. Frederick, 551 U.S. 393 (2007).

Another important restriction on governmental authority actually appears twice in the Constitution. The due processFundamental fairness and decency. clause appears in both the Fifth Amendment (“No person shall…be deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law”) and the Fourteenth Amendment (“Nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law”). The Fifth Amendment applies to the federal government, and after the Civil War, the Fourteenth Amendment made due process applicable to the states as well. At its core, due process means “fundamental fairness and decency.” The clause requires that all government action that involves the taking of life, liberty, or property be done fairly and for fair reasons. Notice that the due process clause applies only to government action—it does not apply to the actions of private citizens or entities such as corporations or, for that matter, to actions of private universities and colleges.

As interpreted by the courts, the due process clause contains two components. The first is called procedural due processGovernment must use fair procedures.. Procedural due process requires that any government action that takes away life, liberty, or property must be made fairly and using fair procedures. In criminal cases, this means that before a government can move to take away life, liberty, or property, the defendant is entitled to at least adequate notice, a hearing, and a neutral judge. For example, in 2009 the Supreme Court held that a state Supreme Court judge’s refusal to remove himself from a case involving a big campaign donor violated the procedural due process clause promise for a neutral judge.

http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=105143851

Hugh Caperton, a small coal mine operator in West Virginia, sued the giant Massey Coal Company, alleging that Massey used illegal tactics to force him out of business. A jury awarded Caperton more than fifty million dollars in damages. When Massey appealed the case to the West Virginia Supreme Court, he spent more than three million dollars on a campaign to defeat an incumbent judge and promote another judge, who then refused to excuse himself from the appeal and ended up casting the swing vote in a 3–2 decision to overturn the fifty-million-dollar award. On appeal to the Supreme Court, the Court held that the judge’s actions violated procedural due process.

The second component of the due process clause is substantive due processLegislation must be fair.. Substantive due process focuses on the content of government legislation itself. Generally speaking, government regulation is justified whenever the government can articulate a rational reason for the regulation. In certain categories, however, the government must articulate a compelling reason for the regulation. This is the case when the regulation affects a fundamental right, which is a right deeply rooted in American history and implicit in the concept of ordered liberty. The government must also set forth compelling reasons for restricting the right to vote or the right to travel. Since substantive due process is a fairly amorphous concept, it is often used as a general basis for any lawsuit challenging government procedures or laws that affect an individual’s or company’s civil liberties.

When Can a State Force Sterilization?

http://www.usatoday.com/news/health/2009-06-23-eugenics-carrie-buck_N.htm

In the early 1920s, the state of Virginia experimented with a eugenics program in an attempt to improve the human race by eliminating “defects” from the human gene pool. As part of this program, Virginia approved a law that would allow the forced sterilization of inmates in state institutions. Eighteen-year-old Carrie Buck became the first woman sterilized under this program. Buck, who had been raped by a nephew, was committed to the Virginia State Colony for Epileptics and Feeble-minded in Lynchburg, Virginia. Her birth mother was also committed, as was her daughter. When Buck challenged Virginia’s law at the Supreme Court, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes overruled her due process objections, holding that “it is better for all the world, if instead of waiting to execute degenerate offspring for crime, or to let them starve for their imbecility, society can prevent those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind…Three generations of imbeciles are enough.”Buck v. Bell, 274 U.S. 200 (1927). Buck became the first of tens of thousands of Americans forced to undergo sterilization as part of a general belief in eugenics, a belief apparently shared by members of the Supreme Court. Read the linked article to learn more about Carrie Buck, including the total lack of any evidence of mental defect when she was sterilized.

Businesses have used the substantive due process clause to limit the award of punitive damagesDamages awarded to plaintiffs not to compensate them for harm caused but to prevent similar conduct by the defendants in the future. in tort cases. They argue that a startlingly high punitive damage award is a state-sanctioned deprivation of property, which means the due process clause is implicated. Furthermore, if the award is grossly excessive, then due process is violated. In 1996 the Supreme Court heard an appeal from German automobile manufacturer BMW arising from a case from Alabama.BMW of North America Inc. v. Gore, 517 U.S. 559 (1996). The plaintiff argued that although he bought his car new, it had in fact suffered some paint damage while in transit to the dealer, and the damage was not disclosed to him. When he found out about the prior damage, he sued BMW, arguing that BMW’s policy (which is that if damage to new cars can be repaired for 3 percent of the car’s value or less, then the car can be repaired and sold as new) damaged the resale value of his car. It cost six hundred dollars to fix the actual damage to his car, and the jury awarded him four thousand dollars in compensatory damages for the lost resale value on his car. The jury then awarded him four million dollars in punitive damages, which the Alabama Supreme Court reduced to two million. The Supreme Court found the punitive damages award unconstitutional under the due process clause. In its holding, the Court said that there are three factors that determine if a punitive damage award is too high. First is the degree of reprehensibility of the defendant’s conduct. Second is the ratio between the compensatory and punitive damage award; generally, this ratio should be less than ten. Finally, courts should compare the punitive damage award with civil or criminal penalties awarded for similar misconduct. The Court reiterated its holding again in a case involving a $145 million punitive damage award against State Farm in a case where the compensatory award was one million dollars.State Farm Mut. Automobile Ins. Co. v. Campbell, 538 U.S. 408 (2003). Interestingly, Justices Scalia and Thomas, both conservative and generally seen as friendly to business interests, dissent from this view, finding that nothing in the due process clause prevents high punitive damage awards.

The final constitutional protection we’ll consider here is the Equal Protection ClauseThe portion of the Fourteenth Amendment requiring states to provide the equal protection of laws to persons within their jurisdiction. of the Fourteenth Amendment. The clause states that “No state shall deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” As discussed previously, this clause incorporates Constitutional protections against the states in addition to the federal government. Although drafted and adopted in response to resistance to efforts at integration of African Americans in the South after the Civil War, the promise of the Equal Protection Clause (enshrined at the Supreme Court building, Figure 5.5 "U.S. Supreme Court Building") continues to find application in all manner of American public life where discrimination is an issue.

Figure 5.5 U.S. Supreme Court Building

Source: Photo courtesy of UpstateNYer, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:CourtEqualJustice.JPG.

The Equal Protection Clause is implicated anytime a law limits the liberty of some people but not others. In other words, it operates to scrutinize government-sponsored discrimination. While the word “discrimination” has a negative connotation, in legal terms not all discrimination is illegal. A criminal law might discriminate against those who steal, for example, in favor of those who don’t steal. The Equal Protection Clause seeks to determine what forms of discrimination are permissible.

To establish a guideline for courts to use in answering equal protection cases, the Supreme Court has established three standards of review when examining statutes that discriminate. The three standards are known as minimal scrutiny, intermediate scrutiny, and strict scrutiny.

In the minimal scrutinyThe standard of review in which government must provide rational basis for the law. test, think of the courts turning on a twenty-watt lightbulb to look at the statute. There’s enough light to see the statute, but the light is so dim that the judges won’t examine the statute in great detail. Under this standard, government needs to put forth only a rational basis for the law—the law simply has to be reasonably related to some legitimate government interest. If the judge is satisfied that the law is based on some rational basis (keeping in mind that with the twenty-watt lightbulb, the inquiry isn’t very deep), then the law passes equal protection. Thus, a law that imprisons thieves easily passes minimal scrutiny, since there are many rational reasons to imprison thieves. As a matter of course, the vast majority of cases that are scrutinized under minimal scrutiny easily pass review. Most laws fall into this category of scrutiny by default—courts apply heightened scrutiny only in special circumstances. Even under this low standard, however, governments must be able to articulate a rational basis for the law. For example, in 1995 Colorado approved a state constitutional amendment that would have prevented any city, town, or county in Colorado from recognizing homosexuals as a protected class of citizens. The Supreme Court struck down the constitutional amendment, finding there was no rational basis for it and that it was in fact motivated by a “bare desire to harm a politically unpopular group.”Romer v. Evans, 517 U.S. 620 (1996).

The intermediate scrutinyThe standard of review in which government must prove the law is substantially related to an important government interest. test is reserved for cases where the government discriminates on the basis of sex or gender. Under this test, the government has to prove that the law in question is substantially related to an important government interest. Think of the courts turning on a sixty-watt lightbulb in this test, because they’re expecting the government to provide more than just a rational justification for the law. Using this test, courts have invalidated gender restrictions on admissions to nursing school, laws that state only wives can receive alimony, and a higher minimum drinking age for men. In one important case, the Supreme Court held that the system for single-sex education at the Virginia Military Institute violated the Equal Protection Clause.United States v. Virginia, 518 U.S. 515 (1996). On the other hand, courts have been willing to tolerate gender discrimination in the male-only Selective Service (military draft) system.

The strict scrutinyThe standard of review in which government must prove the law is justified by a compelling government interest. test is used when the government discriminates against a suspect class. Under this test, the government has to prove that the law is justified by a compelling governmental interest, that the law is narrowly tailored to achieve that goal or interest, and that the law is the least restrictive means to achieve that interest. Here, the courts are turning on a one-hundred-watt lightbulb in examining the law, so they can examine the law in great detail to find justification. The standard is reserved for only a few classifications: laws that affect “fundamental rights” such as the rights in the Bill of Rights and any government discrimination that affects a “suspect classification” such as race or national origin. In practice, when courts find that strict scrutiny applies, a law is very often struck down as unconstitutional because it’s so hard for government to pass this standard of review. Certainly, most laws that discriminate on the basis of race are struck down on this basis. There are a few exceptions, however, where the Supreme Court has held that racial discrimination may be permissible even under strict scrutiny. The first case rose in the height of World War II, when the federal government sought to intern Japanese Americans into camps on the basis that they may pose a national security risk. Fred Korematsu sued the federal government under the equal protection clause, arguing that as an American citizen the government was unfairly discriminating against him on the basis of race, especially in light of the fact that Americans of Italian and German descent were not treated similarly. In a 6–3 decision, the Supreme Court sided with the government.Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214 (1944). Although that decision has never been overturned, the U.S. government officially apologized for the internment camps in the 1980s, paid many millions of dollars in reparationsCompensation for past injury., and eventually awarded Fred Korematsu the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

A second case involving the use of racial discrimination surrounds the issue of affirmative actionThe practice of providing affirmative action to targeted populations to achieve diversity goals. in higher education. Many elite colleges and universities would have no problem filling their entire entering class with stellar academic students with high grade point averages and standardized testing scores. If they did this, however, their classrooms would generally look quite similar, as these students tend to come from a largely white, upper-middle-class socioeconomic profile. In a belief that diversity adds value to the classroom learning experience, the University of Michigan added “points” to an applicant’s profile if the applicant was a student athlete, from a diverse racial background, or from a rural area in Michigan. When this practice was challenged, the Supreme Court found that this point system operated too much like a race quota, which has been illegal since the 1970s, and overturned the system.Gratz v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 244 (2003). In a challenge by a law school applicant denied admission, however, the Supreme Court upheld the law school’s system, which rather than assigning a mathematical formula, used a system where race was only a “potential plus factor” to be considered with many other factors.Grutter v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 306 (2003). After extensive briefing, including a record number of amicus briefs, the Court found that diversity in higher education is a compelling enough state interest that schools could consider race in deciding whether or not to admit students. The Court did caution, however, that schools should move toward race-neutral systems and that affirmative action should not last more than twenty-five more years.

The Bill of Rights provides key civil liberties to all Americans and persons on U.S. soil. These liberties are never absolute, subject to competing interests that courts must balance in making their decisions. These rights also vary from time to time and are generally designed to protect the weakest in society rather than the strongest. Many, but not all, of the restrictions on government activity found in the Bill of Rights also apply to the states through incorporation. The First Amendment prohibits the government from establishing religion and from restricting the free exercise thereof. The First Amendment also prohibits the government from restricting the freedom of speech. Political speech is protected to the fullest extent by the First Amendment, while obscene and defamatory speech is not protected at all but subject to the doctrine of prior restraint. Corporations have some free speech rights under the corporate speech doctrine. Generally speaking, states may impose reasonable time, place, and manner restrictions on the delivery of speech. Procedural due process requires that the government use fair procedures anytime it seeks to deprive a citizen of life, liberty, or property. Substantive due process requires the government to articulate a rational basis for passing laws or, when fundamental rights are involved, to articulate a compelling reason to do so. Substantive due process has been used by the Supreme Court to limit punitive damage amounts. Equal protection requires the government to justify discrimination. In cases of racial discrimination, courts apply strict scrutiny to the law. In cases involving sex or gender discrimination, the courts apply an intermediate level of scrutiny, and in all other cases, courts apply a minimal basis of scrutiny.

For being such a short document, the Constitution can be complex to interpret. The needs of a varied and diverse nation, as well as corporate enterprises, all demand a constitutional framework that is rigid enough to provide strict checks against tyranny by the majority, while flexible enough to adapt to new changing societal values and mores, as well as rapidly changing business conditions. Understanding the framework of government established by the Constitution, the powers of each branch of government, and the substantive rights afforded to individuals and companies is a critical part of being an informed citizen. As our nation faces a new century with both uncertain currents and a future brighter than the Founding Fathers could have envisioned, the Constitution will continue to provide bedrock principles to ensure the “blessings of liberty” to all.