Whenever a company or individual acts unreasonably and causes injury, that person or company may be liable for a tort. In some cases it doesn’t matter how careful or reasonable the company or individual is—they may be liable for any injury resulting from their actions. Torts are an integral part of our civil law, and in this chapter, you’ll learn about what kinds of torts exist and how to defend yourself or your company from potential tort liability. Specifically, you should be able to answer the following questions:

Figure 7.1 A Typical Construction Site

Look at the picture in Figure 7.1 "A Typical Construction Site". You’ve probably seen a similar picture of a construction site near where you live, with multiple orange traffic cones (with reflective stripes so they can be seen at night) and a large sign warning vehicles not to attempt to drive on the road. Now imagine the picture without the traffic cones, warning signs, or caution tape. If you were driving, would you still attempt to drive on this road?

Most of us would probably answer no, since the road is obviously under construction and attempting to drive on it may result in severe damage to property (our vehicles) and personal injury. Similarly, pedestrians, skateboarders, and bicyclists will likely steer clear of this road even if it wasn’t clearly marked or roped off. So if the dangers associated with this construction are obvious, why would the construction workers go through the time and expense of setting up the traffic cones, sign, and tape?

The answer has to do with tortA civil wrong, other than breach of contract. law. A tort can be broadly defined as a civil wrong, other than breach of contract. In other words, a tort is any legally recognizable injury arising from the conduct (or nonconduct, because in some cases failing to act may be a tort) of persons or corporations. The other area of civil law that corporations have to be concerned about is contract law. There are several key differences between torts and contracts.

First is the realm of possible plaintiffs. In contract law, only persons that you have a contract with, or you are a third-party-beneficiary to (such as when you are named the beneficiary to a life insurance policy and the company refuses to pay the claim), can possibly sue you for breach of contract. In tort law, just about anyone can sue you, as long as they can establish that you owe them some sort of legally recognized duty. The second key difference is damages, or remedies. In contract law, damages are usually not difficult to calculate, as contract law seeks to place the parties in the same position as if the bargain had been performed (known as compensatory damagesMoney damages to compensate for economic losses, or losses stemming from injuries.). Compensatory damages also apply in tort law, but they are much more difficult to calculate. Since money cannot bring the dead back to life or regrow a limb, tort law seeks to find a suitable monetary equivalent to those losses, which as you can imagine is a very difficult thing to do. Additionally, tort law generally allows for the award of punitive damagesMoney damages awarded to punish the defendant for gross and wanton negligence and to deter future wrongdoing., something never permitted in contract law.

There is also some intersection between tort law and criminal law. Often, the same conduct can be both a crime and a tort. If Claire punches Charlie in the gut, for example, without provocation and for no reason, then Claire has committed the tort of battery and the crime of battery. In the tort case, Charlie could sue Claire in civil court for money damages (typically for his pain, suffering, and medical bills). That case would be tried based on the civil burden of proof—preponderance of the evidence. That same action, however, could also lead Charlie to file a criminal complaint with the prosecutor’s office. Society is harmed when citizens punch each other in the gut without provocation or justification, so the prosecutor may file a criminal case against Claire, where the people of the state would sue her for the crime of battery. If convicted beyond a reasonable doubt, Claire may have to pay a fine to the people (the government) and may lose her liberty. Charlie gets nothing specifically from Claire in the criminal case other than the general satisfaction of knowing that his attacker has been convicted of a crime.

You might recall from Chapter 3 "Litigation" that the standard of proving a criminal case (beyond a reasonable doubt) is far higher than the standard for proving a civil case (a preponderance of evidence). Therefore, if someone is convicted of a crime, he or she is also automatically liable in civil tort law under the negligence per seNegligence due to a criminal violation. doctrine. For that reason, criminal defendants who wish to avoid a criminal trial are permitted to plead “no contest” to the criminal charges, which permits the judge to sentence them as if they were guilty but preserves the right of the defendant to defend a civil tort suit.

Perhaps more than any other area of law, tort law is a reflection of American societal values. Contracts are enforced because they protect our expectation that our promises are enforced. Criminal law is the result of elected legislatures prohibiting behavior that the community finds offensive or immoral. Tort law, on the other hand, is generally not the result of legislative debate or committee reports. Each tort case arises out of different factual situations, and a jury of peers is asked to decide whether or not the tortfeasorA person who commits a tort. (the person committing the tort) has violated a certain societal norm. Additionally, we expect that when an employee is working for the employer’s benefit and commits a tort, the employer should be liable. Under the respondeat superiorDoctrine that holds employers liable for tortious acts committed by employees while acting within the scope of their employment. doctrine, employers are indeed liable, unless they can demonstrate the employee was on a frolic and detour at the time he or she committed the tort.

The norms that society protects make up the basis for tort law. For example, we have an expectation that we have the right to move freely without interference unless detained pursuant to law. If someone interferes with that right, he or she commits the tort of false imprisonment. We have an expectation that if someone spills a jug of milk in a grocery store, the store owners will promptly warn other customers of a slippery floor and clean up the spill. Failure to do so might constitute the tort of negligence. Likewise, we expect that the products we purchase for everyday use won’t suddenly and without explanation injure us, and if that happens then a tort has taken place.

It has been said many times that tort law is a unique feature of American law. In Asian countries that follow a Buddhist tradition, for example, many people have a belief that change is a constant part of life and to resist that change is to cause human suffering. Rather than seeking to blame someone else for change (such as an injury, death, or damage to personal property), a Buddhist may see it as part of that person’s or thing’s “nature” to change. In countries with an Islamic tradition, virtually all events are seen as the will of God, so an accident or tragedy that leads to injury or death is accepted as part of one’s submission to God. In the United States, however, the tradition is one of questioning and inquiry when accidents happen. Indeed, it can be said with some truth that many Americans believe there is no such thing as an accident—if someone is injured or killed unexpectedly, we almost immediately seek to explain what happened (and then often place blame).

Torts can be broadly categorized into three categories, depending on the level of intent demonstrated by the tortfeasor. If the tortfeasor acted with intent to cause the damage or harm that results from his or her action, then an intentional tortA type of tort where the defendant acts with intent to cause a particular outcome. has occurred. If the tortfeasor didn’t act intentionally but nonetheless failed to act in a way a reasonable person would have acted, then negligenceThe breach of the duty of all persons, as established by state tort law, to act reasonably and to exercise a reasonable amount of care in their dealings and interactions with others. has taken place. Finally, if the tortfeasor is engaged in certain activities and someone is injured or killed, then under strict liabilityLiability imposed in certain situations without regard to fault or due care. the tortfeasor is held liable no matter how careful or careless he or she may have been. In this chapter, we’ll explore these three areas of torts carefully so that by the end of the chapter, you’ll understand the responsibilities tort law imposes on both persons and corporations. The chapter concludes with a brief discussion of other issues that affect torts, including tort reform.

A tort is a civil wrong (other than breach of contract) arising out of conduct or nonconduct that violates societal norms as determined by the judicial system. Unlike contracts and crimes, torts do not require legislative action. Torts protect certain expectations we cherish in a free society, such as the right to travel freely and to enjoy our property. There are three primary areas of tort law, classified depending on the level of intent demonstrated by the tortfeasor.

Examine Figure 7.2 "A Coworker Attacks". The office worker on the right has grabbed the office worker on the left and is strangling him. This conduct is clearly criminal, and it is also tortious. Since the tortfeasor here has acted intentionally by grabbing his colleague’s neck, the tort is considered intentional. (It is, in fact, likely assault and battery.)

In an intentional tort, the tortfeasor intends the consequences of his or her act, or knew with substantial certainty that certain consequences would result from the act. This intent can be transferred. For example, if someone swings a baseball bat at you, you see it coming and duck, and the baseball bat continues to travel and hits the person standing next to you, then the person hit is the victim of a tort even if the person swinging the bat had no intention of hitting the victim.

In addition to the physical pain that accompanies being strangled by a coworker, the victim may also feel a great deal of fear. That fear is something we expect to never have to feel, and that fear creates the basis for the tort of assaultAn intentional, unexcused act that creates in another person a reasonable apprehension or fear of immediate harmful or offensive contact.. An assault is an intentional, unexcused act that creates in another person a reasonable apprehension or fear of immediate harmful or offensive contact. Note that actual fear is not required for assault—mere apprehension is enough. For example, have you ever gone to sit down on a chair only to find out that one of your friends has pulled the chair away, and therefore you are about to fall down when you sit? That sense of apprehension is enough for assault. Similarly, a diminutive ninety-pound woman who attempts to hit a burly three-hundred-pound police officer with her bare fists is liable for assault if the police officer feels apprehension, even if fear is unlikely or not present. Physical injuries aren’t required for assault. It’s also not necessary for the tortfeasor to intend to cause apprehension or fear. For example, if someone pointed a very realistic-looking toy pistol at a stranger and said “give me all your money” as a joke, it would still constitute assault if a reasonable person would have perceived fear or apprehension in that situation. The intentional element of assault exists here, because the tortfeasor intended to point the realistic-looking toy pistol at the stranger.

A batteryAny unconsented touching. is a completed assault. It is any unconsented touching, even if physical injuries aren’t present. In battery, the contact or touching doesn’t have to be in person. Grabbing someone’s clothing or cane, swinging a baseball bat at someone sitting in a car, or shooting a gun (or Nerf ball, for that matter, if it’s unconsented) at someone is considered battery. Notice that assault and battery aren’t always present together. Shooting someone in the back usually results in battery but not assault since the victim didn’t see the bullet coming and therefore did not feel fear or apprehension. Similarly, a surgeon who performs unwanted surgery or a dentist who molests a patient while the patient is sedated has committed battery but not assault. Sending someone poisoned brownies in the mail would be battery but not assault. On the other hand, spitting in someone’s face, or leaning in for an unwanted kiss, would be assault and possibly battery if the spit hit the victim’s face, or the kiss connected with any part of the victim’s body.

When someone is sued for assault or battery, several defenses are available. The first is consent. For example, players on a sports team or boxers in a ring are presumed to have consented to being battered. Self-defenseReasonable and proportionate force to defend oneself from harm or injury. and defense of othersReasonable and proportionate force used to defend another person from harm or injury. are also available defenses, bearing in mind that any self-defense must be proportionate to the initial force.

A battery must result in some form of physical touching of the plaintiff. When that physical touching is absent, courts sometimes permit another tort to be claimed instead, the tort of intentional infliction of emotional distress (IIED)Extreme and outrageous conduct (measured objectively) that intentionally or recklessly causes severe emotional distress to another.. In a sense, IIED can be thought of as battery to emotions, but a great deal of caution is warranted here. Many people are battered emotionally every day to varying degrees. Someone may cut you off in traffic, leading you to curse at him or her in anger. A stranger may cut in line in front of you, leading you to exclaim in indignation. A boyfriend or girlfriend may decide to break off a relationship with you, leading to hurt feelings and genuine grief or pain. None of these situations, nor any of the normal everyday stresses of day-to-day living, are meant to be actionable in tort law. The insults, indignities, annoyances, or even threats that we experience as part of living in modern society are to be expected. Instead, IIED is meant to protect only against the most extreme of behaviors. In fact, for a plaintiff to win an IIED case, the plaintiff has to demonstrate that the defendant acted in such a manner that if the facts of the case were told to a reasonable member of the community, that community member would exclaim that the behavior is “outrageous.” Notice that the standard here is objective; it’s not enough for the plaintiff to feel that the defendant has acted outrageously. In some states, the concern that this tort could be abused and result in frivolous litigation has led to the additional burden that the plaintiff must demonstrate some physical manifestation of the psychological harm (such as sleeplessness or depression) to win any recovery.

http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=5192571

The Westboro Baptist Church is a small (approximately seventy-member) fundamentalist church based in Topeka, Kansas. Members of the church, led by their pastor, Fred Phelps, believe that American soldier deaths in Iraq and Afghanistan are punishment from God for the country’s tolerance of homosexuality. Church members travel around the country to picket at the funerals of fallen soldiers with large bold signs. Some of the signs proclaim “Thank God for Dead Soldiers.” In 2006 members of the church picketed the funeral of Marine Lance Corporal Matthew Snyder, and Snyder’s father sued Phelps and the church for IIED and other tort claims. The jury awarded Snyder’s family over $5 million in damages, but on appeal, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit overturned the verdict. The court found the speech “distasteful and repugnant” but pointed out that “judges defending the Constitution must sometimes share their foxhole with scoundrels of every sort, but to abandon the post because of the poor company is to sell freedom cheaply. It is a fair summary of history to say that the safeguards of liberty have often been forged in controversies involving not very nice people.”Snyder v. Phelps, 580 F.3d 206 (4th Cir. 2009), http://pacer.ca4.uscourts.gov/opinion.pdf/081026.P.pdf (accessed September 27, 2010). Adding insult to injury, the Court of Appeals ordered Snyder’s family to pay over $16,000 in legal fees to the church, which led to an outpouring of support for Snyder on Facebook.“I Support Al Snyder in His Fight against Westboro Baptist Church,” Facebook. http://www.facebook.com/group.php?v=wall&ref=ts&gid=355406162379 (accessed September 27, 2010). The U.S. Supreme Court has accepted the case.

Although the standard for outrageous conduct is objective, the measurement is made against the particular sensitivities of the plaintiff. Exploiting a known sensitivity in a child, the elderly, or pregnant women can constitute IIED. A prank telephone call made by someone pretending to be from the army to a mother whose son was at war, telling the mother her son has been killed, would most certainly be IIED.

Companies must be careful when handling sensitive employment situations to avoid potential IIED liability. This is especially true when terminating or laying off employees. Such actions must be taken with care and civility. Similarly, companies involved in a lot of public interactions should be careful of this tort as well. Bill collectors and foreclosure agencies must be careful not to harass, intimidate, or threaten the people they deal with daily. In one foreclosure case, for example, Bank of America was sued by a mortgage borrower when the bank’s local contractor entered the home of the borrower, cut off utilities, padlocked the door, and confiscated her pet parrot for more than a week, causing severe emotional distress.James Hagerty, “Bank Sorry for Taking Parrot,” Wall Street Journal, March 11, 2010, A1. In 2006, Walgreens was sued for IIED when pharmacists accidentally stapled a form to patient drugs that was not meant to be seen by patients. The form was supposed to annotate notes about patients, but some pharmacists filled in the form with comments such as “Crazy! She’s really a psycho! Do not say her name too loud; never mention her meds by name.”“Walgreens Pharmacists Mock You behind Your Back,” The Consumerist, March 8, 2006, http://consumerist.com/2006/03/walgreens-pharmacists-mock-you-behind-your-back.html (accessed September 27, 2010).

Figure 7.3 Russell Christoff

Another intentional tort is the invasion of privacyThe intrusion into the personal life of another without legal justification.. There are several forms of this tort, with the most common being misappropriationUsing another’s name, likeness, or identifying characteristic without his or her permission.. Misappropriation takes place when a person or company uses someone else’s name, likeness, or other identifying characteristic without permission. For example, in 1986 model Russell Christoff posed for a photo shoot for Nestlé Canada for Taster’s Choice coffee. He was paid $250 and promised $2,000 if Nestlé used his photo on its product. In 2002 he discovered Nestlé had indeed used his photo on Taster’s Choice coffee without his permission (Figure 7.3 "Russell Christoff"), and he sued Nestlé for misappropriation. A California jury awarded him over $15 million in damages.Jaime Holguin, “$15.6M Award for Coffee ‘Mug,’” CBSnews.com, February 2, 2005, http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2005/02/01/national/main670754.shtml (accessed September 27, 2010). Misappropriation can be a very broad tort because it covers more than just a photograph or drawing being used without permission—it covers any likeness or identifying characteristic. For example, in 1988 Ford Motor Company approached Bette Midler to sing a song for a commercial, which she declined to do. The company then hired someone who sounded just like Midler to sing one of Midler’s songs, and asked her to sound as much like Midler as possible. The company had legally obtained the copyright permission to use the song, but Midler sued anyway, claiming that the company had committed misappropriation by using someone who sounded like her to perform the commercial. An appellate court held that while Ford did not commit copyright infringement, it had misappropriated Midler’s right to publicity by hiring the sound-alike,Midler v. Ford Motor Company, 849 F.3d 460 (9th Cir. 1988). and a jury awarded her over $400,000 in damages.

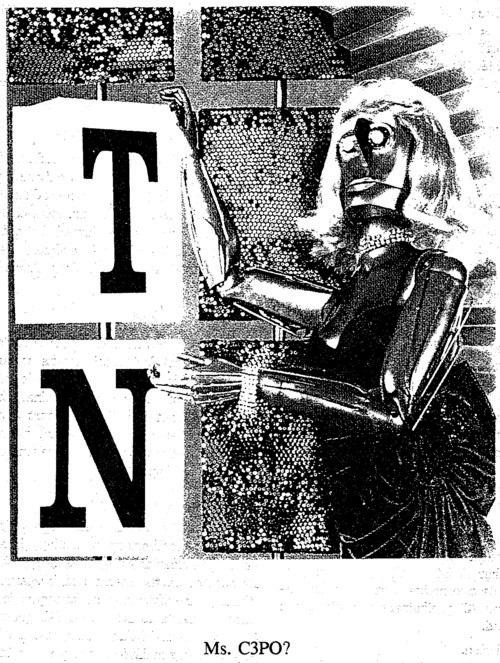

In addition to someone’s voice, an identifying characteristic can be the basis for misappropriation. For example, Samsung Electronics ran a series of print advertisements to demonstrate how long-lasting their products can be. The ads featured a common item from popular culture along with a humorous tagline. One of the ads featured a female robot dressed in a wig, gown, and jewelry posed next to a game show board that looked exactly like the game show board from Wheel of Fortune (Figure 7.4 "Samsung Advertisement"). The tagline said, “Longest-running game show. 2012 A.D.” An appellate court held that Vanna White’s claim for misappropriation was valid, writing “the law protects the celebrity’s sole right to exploit [their identity] value whether the celebrity has achieved her fame out of rare ability, dumb luck, or a combination thereof.”White v. Samsung Electronics America, 971 F.2d 1395 (9th Cir. 1992). The lesson for companies is that in product marketing, permission must be carefully obtained from all persons appearing in their marketing materials, as well as any persons who might have a claim to their likeness or identifying characteristic in the materials.

Figure 7.4 Samsung Advertisement

Source: Photo courtesy of the U.S. federal government, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:White-v-samsung-dissent-appendix-2.png.

Invasion of privacy can also take the form of an invasion of physical solitude. Actions such as window peeping, eavesdropping, and going through someone’s garbage to find confidential information such as bank or brokerage statements are all examples of this form of tort. Media that are overly aggressive in pursuing photos of private citizens may sometimes run afoul of this tort.

Another important intentional tort for businesses is false imprisonmentIntentionally confining or restraining another person’s movement without justification.. This tort takes place when someone intentionally confines or restrains another person’s movement or activities without justification. The interest being protected here is your right to travel and move about freely without impediment. This tort requires an actual and present confinement. If your professor locks the doors to the classroom and declares no one may leave, that is false imprisonment. If the professor leaves the doors unlocked but declares that anyone who leaves will get an F in the course, that is not false imprisonment. On the other hand, a threat to detain personal property can be false imprisonment, such as if your professor grabs your laptop and says, “If you leave, I’ll keep your laptop.” Companies that engage in employee morale-building activities should bear in mind that forcing employees to do something they don’t want to do raises issues of false imprisonment. False imprisonment is especially troublesome for retailers and other businesses that interact regularly with the public, such as hotels and restaurants. If such a business causes a customer to become arrested by the police, for example, it may lead to the tort of false imprisonment. In one case, a pharmacist who suspected a customer of forging a prescription deliberately caused the customer to be detained by the police. When the prescription was later validated, the pharmacist was sued for false imprisonment. Businesses confronted with potential thieves are permitted to detain suspects until police arrive at the establishment; this is known as the shopkeeper’s privilegeThe right of a business owner to detain a suspected shoplifter for a reasonable period of time and under reasonable conditions.. The detention must be reasonable, however. Store employees must not use excessive force in detaining the suspect, and the grounds, manner, and time of the detention must be reasonable or the store may be liable for false imprisonment.

Intentional torts can also be committed against property. Trespass to landIntentional entry to land owned by another without a legal excuse. occurs whenever someone enters onto, above, or below the surface of land owned by someone else without the owner’s permission. The trespass can be momentary or fleeting. Soot, smoke, noise, odor, or even a flying arrow or bullet can all become the basis for trespass. A particular trespass problem takes place in suburban neighborhoods without clearly marked property lines between homes. Children are often regular trespassers in this area, and even if they are trespassing, homeowners are under a reasonable duty of care to ensure they are not harmed. When there is an attractive nuisanceAny item or condition on a property that would be attractive and dangerous to children, even if the children are trespassing. on the property, homeowners must take care to both warn children about the attractive nuisance and protect them from harm posed by the attractive nuisance. This doctrine can apply to pools, abandoned cars, refrigerators left out for collection, trampolines, piles of sand or lumber, or anything that might pose a danger to children and that they cannot understand or appreciate. There may be times, however, when trespass is justified. Obviously, someone invited by the owner is not a trespasser; such a person is considered an invitee until the owner asks him or her to leave. Someone may have a license to trespass, such as a meter reader or utility repair technician. There may also be times when it may be necessary to trespass—for example, to rescue someone in distress.

Trespass to personal propertyUnlawful taking or harming of another person’s property without the owner’s permission. is the unlawful taking or harming of another’s personal property without the owner’s permission. If your roommate borrowed your vehicle without your permission, for example, it would be trespass to personal property. The tort of conversionCivil tort of stealing property from another person. takes place when someone takes your property permanently; it is the civil equivalent to the crime of theft. If you gave your roommate permission to borrow your car for a day and he or she stole your car instead, it would be conversion rather than trespass. An employer who refuses to pay you for your work has committed conversion.

Another intentional tort is defamationPublishing or saying untrue statements about a living person that harms his or her reputation., which is the act of wrongfully hurting a living person’s good reputation. Oral defamation is considered slanderOral form of defamation., while written defamation is libelWritten form of defamation.. To be liable for defamation, the words must be published to a third party. There is no liability for defamatory words written in a secret diary, for example, but there is liability for defamatory remarks left on a Facebook wall. Issues sometimes arise with regard to celebrities and public figures, who often believe they are defamed by sensationalist “news” organizations that cover celebrity gossip. The First Amendment provides strong protection for these news organizations, and courts have held that public figures must show actual maliceConscious, intentional wrongdoing. before they can win a defamation lawsuit, which means they have to demonstrate the media outlet knew what it was publishing was false or published the information with reckless disregard for the truth. This is a much higher standard than that which applies to ordinary citizens, so public figures typically have a difficult time winning defamation lawsuits. Of course, truth is a complete defense to defamation.

Defamation can also take place against goods or products instead of people. In most states, injurious falsehood (or trade disparagement)Publishing false information about another person’s product. takes place when someone publishes false information about another person’s product. For example, in 1988 the influential product testing magazine Consumer Reports published a test of the Suzuki Samurai small SUV, claiming that it “easily rolls over in turns.” Product sales dropped sharply, and Suzuki sued Consumers Union, the publisher, for trade disparagement. The case was settled nearly a decade later after a long and expensive legal battle.

Businesses often make claims about their products in marketing their products to the public. If these claims are false, then the business may be liable for the tort of misrepresentation, known in some states as fraudThe misrepresentation of facts (lying) with knowledge they are false or with reckless disregard for the truth.. Fraud requires the tortfeasor to misrepresent facts (not opinions) with knowledge that they are false or with reckless disregard for the truth. An “innocent” misrepresentation, such as someone who lies without knowing he or she is lying, is not enough—the defendant must know he or she is lying. Fraud can arise in any number of business situations, such as lying on your résumé to gain employment, lying on a credit application to obtain credit or to rent an apartment, or in product marketing. Here, there is a fine line between pufferyPromotional statements expressing subjective views., or seller’s talk, and an actual lie. If an advertisement claims that a particular car is the “fastest new car you can buy,” then fraud liability arises if there is in fact a car that travels faster. On the other hand, an advertisement that promises “unparalleled luxury” is only puffery since it is opinion. Makers of various medicinal supplements and vitamins are often the target of fraud lawsuits for making false claims about their products.

Finally, an important intentional tort to keep in mind is tortious interferenceIntentional damage of another person’s valid contractual relationship.. This tort, which varies widely by state, prohibits the intentional interference with a valid and enforceable contract. If the defendant knew of the contract and then intentionally caused a party to break the contract, then the defendant may be liable. In 1983 oil giant Pennzoil made a bid for a smaller oil rival, Getty Oil. A competitor to Pennzoil, Texaco, found out about the deal and approached Getty with another bid for a higher amount, which Getty then accepted. Pennzoil sued Texaco, and a jury awarded over $10 billion in damages.

Assault is any intentional act that creates in another person a reasonable fear or apprehension of harmful or offensive contact. A battery is a completed assault, when the harmful or offensive contact occurs. The intentional infliction of emotional distress (IIED) is extreme and outrageous conduct that intentionally causes severe emotional distress to another person. In some states, IIED requires a demonstration of physical harm such as sleeplessness or depression. This is a difficult tort to win because of its inherent clash with values embodied by the First Amendment. Misappropriation is the use of another person’s name, likeness, or other identifying characteristic without permission. False imprisonment occurs when someone intentionally confines or restrains another person’s movement without justification. Trespass is the entry onto land without the owner’s permission, while conversion is the civil equivalent of the theft crime. Defamation is the intentional harm to a living person’s reputation, while trade disparagement takes place when someone publishes false information about someone else’s product. Fraudulent misrepresentation is any intentional lie involving facts. Tortious interference is the intentional act of causing someone to break a valid and enforceable contract.

Ordinarily, we don’t expect perfectly good airplanes to fall out of the sky for no reason. When it happens, and it turns out that the reason was carelessness or a failure to act reasonably, then the tort of negligenceThe breach of the duty of all persons, as established by state tort law, to act reasonably and to exercise a reasonable amount of care in their dealings and interactions with others. may apply. All persons, as established by state tort law, have the duty to act reasonably and to exercise a reasonable amount of care in their dealings and interactions with others. Breach of that duty, which causes injury, is negligence. Negligence is distinguished from intentional torts because there is a lack of intent to cause harm. If a pilot intentionally crashed an airplane and harmed others, for example, the tort committed may be assault or battery. When there is no intent to harm, then negligence may nonetheless apply and hold the pilot or the airline liable, for being careless or failure to exercise due care.

Note that the definition of negligence is purposefully broad. Negligence is about breaching the duty we owe others, as determined by state tort law. This duty is often broader than the duties imposed by law. Colgan Air, for example, may have been fully compliant with applicable laws passed by Congress while still being negligent. In a way, the law of negligence is an expression of democracy at the community and local level, because ultimately, citizen juries (as opposed to legislatures) decide what conduct leads to liability.

To prove negligence, plaintiffs have to demonstrate four elements are present. First, they have to establish that the defendant owed a duty to the plaintiff. Second, the plaintiff has to demonstrate that the defendant breached that duty. Third, the plaintiff has to prove that the defendant’s conduct caused the injury. Finally, the plaintiff has to demonstrate legally recognizable injuries. We’ll address each of these elements in turn.

First, the plaintiff has to demonstrate that the defendant owed it a duty of care. The general rule in our society is that people are free to act any way they want to, as long as they don’t infringe on the freedoms or interests of others. That means that you don’t owe anyone a special duty to help them in any way. For example, if you’re driving along a deserted rural highway at night in a snowstorm, and you see a car ahead of you fishtail and drive into a ditch, you are entitled to keep driving and do nothing, not even report the accident, because you don’t owe that driver any special duty. On the other hand, if you ran a stop sign, which then caused the other driver to drive into a ditch, you would owe that driver a duty of care.

Another way to look at duty is to consider whether or not the plaintiff is a foreseeable plaintiff. In other words, if the risk of harm is foreseeable, then the duty exists. Take, for instance, the act of littering with a banana peel. If you carelessly throw away a banana peel, then it is foreseeable that someone walking along may slip on it and fall, causing injuries. Under tort law, by throwing away the banana peel you now owe a duty to anyone who may be walking nearby who might walk on that banana peel, because any of those persons might foreseeably step on the peel and slip.

An emerging area in tort law is whether or not businesses have a duty to warn or protect customers for random crimes committed by other customers. By definition, crimes are random and therefore not foreseeable. However, some cases have determined that if a business knows about, or should know about, a high likelihood of crime occurring, then that business must warn or take steps to protect its customers. For example, in one case a state supreme court held that when a worker at Burger King ignored a group of boisterous and loud teenagers, Burger King was liable when those teenagers then assaulted other customers.Iannelli v. Burger King Corp., 145 N.H. 190 (2000). In another case, the Las Vegas Hilton was held liable for sexual assault committed by a group of naval aviators because evidence at trial revealed that the hotel was aware of a history of sexual misconduct by the group involved.

The concept of duty is broad and extends beyond those in immediate physical proximity. In a famous case from California, for example, a radio station with a large teenage audience held a contest with a mobile DJ announcing clues to his locations as he moved around the city. The first listener to figure out his location and reach him earned a cash prize. One particular listener, a minor, was rushing toward the DJ when the listener negligently caused a car accident, killing the other driver. During a negligence trial, the radio station argued that hindsight is not foreseeability and that the station therefore did not owe the dead driver a duty of care. The California Supreme Court held that when the radio station started the contest, it was foreseeable that a young and inexperienced driver may drive negligently to claim the prize and that therefore a duty of care existed.Weirum v. RKO General, 15 Cal.3d 40 (1975). Radio stations should therefore be very careful when running promotional contests to ensure that foreseeable deaths or injuries are prevented. This lesson apparently eluded Sacramento station KDND, which in 2007 held a contest titled “Hold Your Wee for a Wii” where contestants were asked to drink a large amount of water without going to the bathroom for the chance of winning a game console. An otherwise healthy twenty-eight-year-old mother died of water intoxication hours after the contest, which led to a lawsuit and a $16 million jury verdict.

The general rules surrounding when a duty exists can be modified in special situations. For example, landowners owe a duty to exercise reasonable care to protect persons on their property from foreseeable harm, even if those persons are trespassers. If you are aware of a weak step or a faucet that dispenses only scalding hot water, for example, you must take steps to warn guests about those known dangers.

Businesses owe a duty to exercise a reasonable degree of care to protect the public from foreseeable risks that the owner knew or should have known about. There are many foreseeable ways for customers to be injured in retail stores, from falling objects improperly placed on high shelves, to light fixtures exploding or falling due to improper installation, to customers being injured by forklifts in so-called warehouse stores. One particular area of concern for businesses is liquid on walking surfaces, which can be very dangerous. Spilled product (milk, orange juice, wine, etc.), melted ice or snow, or rain can cause slick situations, and if a store knows about such a condition, or should have known about it, then the store must quickly warn customers and remedy the situation.

Business professionals such as doctors, accountants, dentists, architects, and lawyers owe a special duty to act as a reasonable person in their profession. Professional negligence by these professionals is known as malpracticeNegligence committed by certain professionals.. The government estimates that between forty-four thousand and ninety-eight thousand people die each year in hospitals due to medical mistakes, the vast majority of them preventable.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, “Reducing Errors in Health Care: Translating Research Into Practice,” April 2000, http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/errors.htm (accessed September 27, 2010).

Once duty has been established, negligence plaintiffs have to demonstrate that the defendant breached that duty. A breach is demonstrated by showing the defendant failed to act reasonably, when compared with a reasonable person. It’s important to keep in mind that this reasonable person is hypothetical and does not actually exist. This reasonable person is never tired, sleepy, angry, or intoxicated. He or she is reasonably careful—not taking every single precaution to prevent accidents but considering his or her actions and consequences carefully before proceeding. In reality, once a duty has been established, the presence of injury or harm is usually enough to satisfy the “breach of duty” requirement.

The third element of negligence is causation. In deciding whether there is causation, courts have to consider two questions. First, courts query as to whether there is causation in fact, also known as but-for causation. This form of causation is fairly easy to prove. But for the defendant’s actions, would the plaintiff have been injured? If yes, then but-for causation is proven. For example, if you are texting while driving and you hit a pedestrian because your attention was diverted, then but-for causation is easily met, because “but for” your actions of texting while driving, you would not have hit the pedestrian.

The second question is tougher to establish. It asks whether the defendant’s actions were the proximate cause of the plaintiff’s injury. In asking this question, courts are expressing a concern that causation-in-fact can be taken to a logical but extreme conclusion. For example, if a speeding truck driver crashes his or her rig and causes the interstate highway to be shut down for several hours, causing you to become stuck in traffic and miss an important interview, you could argue that but for the truck driver’s negligence, you may have landed a new job. It would not be fair, however, to hold the truck driver liable for all the missed appointments and meetings caused by a subsequent traffic jam after the crash. At some point, the law has to break the chain of causation. The truck driver may be liable for injuries caused in the crash, but not beyond the crash. This is proximate causationAn act from which an injury results as a natural and direct consequence..

In determining whether proximate cause exists, we once again use the foreseeability test, already used for determining whether duty exists. If an injury is foreseeable, then proximate cause exists. If it is unforeseeable, then it does not.

In some cases it can be difficult to pinpoint a particular source for a product, which then makes proving causation difficult. This is particularly true in mass tortA civil tort involving numerous plaintiffs against one or few defendants. cases where victims may have been exposed to dangerous substances from multiple sources over a number of years. For example, assume that you have been taking a vitamin supplement for a number of years, buying the supplement from different companies that sell it. After a while the government announces that this supplement can be harmful to health and orders sales to stop. You find out that your health has been affected by this supplement and decide to file a tort lawsuit. The problem is that you don’t know which manufacturer’s supplement caused you to fall ill, so you cannot prove any specific manufacturer caused your illness. Under the doctrine of joint and several liabilityA doctrine under which the plaintiff may pursue a claim against any party liable for the claim as if they were jointly liable, and defendants then sort out their respective proportions of liability., however, you don’t have to identify the specific manufacturer that sold you the drug that made you ill. You can simply sue one, two, or all manufacturers of the supplement, and any of the defendants are then liable for the entirety of your damages if they are found liable. This doctrine has been used in cases involving asbestos production and distribution.

The final element in negligence is legally recognizable injuries. If someone walks on a discarded banana peel and doesn’t slip or fall, for example, then there is no tort. If someone has been injured, then damages may be awarded to compensate for those injuries. These damages take the form of money, as there is nothing tort law can do to bring back the dead or regrow lost limbs, and tort law does not allow for incarceration. Money is therefore the only appropriate measure of damages, and it is left to the jury to decide how much money a plaintiff should be awarded.

There are two types of award damages in tort law. The first, compensatory damages, seeks to compensate the plaintiff for his or her injuries. Compensatory damagesCompensation for actual injuries suffered by a plaintiff. can be awarded for medical injuries, economic injuries (such as loss of a car, property, or income), and pain and suffering. They can also be awarded for past, present, and future losses. While medical and economic damages can be calculated using available standards, pain and suffering is a far more nebulous concept. Juries are often left to their conscience to decide what amount of money can compensate for pain and suffering, based on the severity and duration of the pain as well as its impacts on the plaintiff’s life.

The second type of damage award is known as punitive damagesMoney awarded to the plaintiff when the defendant acts wantonly, to punish the defendant and to deter future wrongdoing.. Here, the jury is awarded a sum of money not to compensate the plaintiff but to deter the defendant from ever engaging in similar conduct. The idea behind punitive damages is that compensatory damages may be inadequate to deter future bad conduct, so additional damages are necessary to ensure the defendant corrects its ways to prevent future injuries. Punitive damages are available in cases where the defendant acted with willful and wanton negligence, a higher level of negligence than ordinary negligence. Bear in mind, however, that there are constitutional limits to the award of punitive damages.

A defendant being sued for negligence has three basic affirmative defenses. An affirmative defenseA response by the defendant that raises a justification or excuse for the defendant’s conduct. is one that is raised by the defendant essentially admitting that the four elements for negligence are present, but that the defendant is nonetheless not liable for the tort. The first defense is assumption of riskA defense in which the plaintiff is barred from recovery because the plaintiff voluntarily and knowingly assumed known risks.. If the plaintiff knowingly and voluntarily assumes the risk of participating in a dangerous activity, then the defendant is not liable for injuries incurred. For example, if you decide to bungee jump, you assume the risk that you might be injured during the jump. It’s common for bungee jumpers to experience burst blood vessels in the eye, soreness in the back and neck region, and twisted ankles, so these injuries are not compensable. On the other hand, you can only assume risks that you know about. When a person bungee jumps, one of the first steps is for the jump operator to weigh the jumper, so that the length of the bungee can be adjusted accordingly. If this is not done properly, the jumper may overshoot or undershoot the expected bottom of the jump. While you can assume known risks from bungee jumping, you cannot assume unknown risks, such as the risk that a jump operator may negligently calculate the length of the bungee rope.

A related doctrine, the open and obviousA doctrine under which the landowner is protected from liability if an invitee is injured by an open and obvious danger or hazard. doctrine, is used to defend against suits by persons injured while on someone else’s property. For example, if there is a spill on a store’s floor and the store owner has put up a sign that says “Caution—Slippery Floor,” yet someone decides to run through the spill anyway, then that person would lose a negligence lawsuit if he or she slips and falls because the spill was open and obvious. Use of the open and obvious doctrine varies widely by state, with some states allowing it to be used in a wide variety of premises liability cases and other states circumventing its usefulness.

Both the assumption of risk and open and obvious defenses are not available to the defendant who caused a dangerous situation in the first place. For example, if you negligently start a house fire while playing with matches and evacuate the house with your roommates, if one of your roommates decides to reenter the burning house to rescue someone else, you cannot rely on assumption of risk as a defense since you started the fire.

The second defense to negligence is to allege that the plaintiff’s own negligence contributed to his or her injuries. In a state that follows the contributory negligenceAn absolute defense in situations where the plaintiff contributed to his or her own injuries. rule, a plaintiff’s own negligence, no matter how minor, bars the plaintiff from any recovery. This is a fairly harsh rule, so most states follow the comparative negligenceA partial defense that reduces the plaintiff’s recovery by the amount of the plaintiff’s own negligence. rule instead. Under this rule, the jury is asked to determine to what extent the plaintiff is at fault, and the plaintiff’s total recovery is then reduced by that percentage. For example, if you jaywalk across the street during a torrential thunderstorm and a speeding car strikes you, a jury may determine that you are 20 percent at fault for your injuries. If the jury decides that your total compensatory damage award is $1 million, then the award will be reduced by $200,000 to account for your own negligence.

Finally, in some situations, the Good Samaritan lawState laws that shield those who aid the injured from negligence liability. may be a defense in a negligence suit. Good Samaritan statutes are designed to remove any hesitation a bystander in an accident may have to providing first aid or other assistance. They vary widely by state, but most provide immunity from negligent acts that take place while the defendant is rendering emergency medical assistance. Most states limit Good Samaritan laws to laypersons (i.e., police, emergency medical service providers, and other first responders are still liable if they act negligently) and to medical actions only.

Negligence imposes a duty on all persons to act reasonably and to exercise due care in dealing and interacting with others. There are four elements to the tort of negligence. First, the plaintiff must demonstrate the defendant owed the plaintiff a duty. If the risk of injury is foreseeable, then the defendant owes the plaintiff a duty. Second, there must be a breach of that duty. A breach occurs when the defendant fails to act like a reasonable person. Professional negligence is known as malpractice. Third, the plaintiff must demonstrate that the defendant caused the plaintiff’s injuries. Both causation-in-fact and proximate causation must be proven. Finally, the plaintiff must demonstrate legally recognizable injuries, which include past, present, and future economic, medical, and pain and suffering damages. Defendants can raise several affirmative defenses to negligence, including assumption of risk, comparative or contributory negligence, and in some cases, Good Samaritan statutes.

Intentional torts require some level of intent to be committed, such as the intent to batter someone. Negligence torts don’t require intent to harm but require some level of carelessness or neglect. Strict liabilityLiability without fault. torts require neither intent nor carelessness. In fact, if strict liability applies, it is irrelevant how carelessly, or how carefully, the defendant acted. It doesn’t matter if the defendant took every precaution to avoid harm—if someone is harmed in a situation where strict liability applies, then the defendant is liable.

Since this rule can have harsh consequences, it applies in a only few limited circumstances. One of those circumstances is when the defendant is engaged in an ultrahazardous activityAn activity so inherently dangerous that those who undertake the activity and cause injuries are strictly liable.. An ultrahazardous activity is one that is so inherently dangerous that the risk to human life is great if anything wrong happens, so the person carrying out the ultrahazardous activity is held strictly liable for those activities. Transporting dangerous chemicals or nuclear waste, for example, is inherently dangerous. If the chemicals spill, it is very difficult, if not impossible, to prevent injury to property or persons. Similarly, businesses that use dynamite, such as building demolition crews, run the risk that no matter how careful they are, people or property could be damaged by intentionally igniting dynamite. Therefore, strict liability applies.

Strict liability also applies when restaurants, bars, and taverns serve alcohol to minors or visibly intoxicated persons. This activity is dangerous, and there is a high risk of probability that these patrons, if they drive, will injure others. Many states have dram shop actsState laws establishing strict liability for taverns, bars, and restaurants for serving alcohol to minor or visibly intoxicated persons who then cause death or injury to others. that impose strict liability in this circumstance.

You might wonder why defendants are held strictly liable if they are acting reasonably or are even being ultracautious. As with most issues in law, the answer lies in social policy. In essence, strict liability torts exist because businesses that engage in covered activities (such as transporting hazardous chemicals or operating bars) profit from those activities. They are also in the best position to ensure that every precaution can be taken to avoid an unexpected event, which may have catastrophic consequences. Victims of these events are often innocent members of the public who are not in any position to avoid being injured and therefore should not be denied a legal remedy simply because the defendant took prudent precautions. This social policy concern is also expressed in the most important area of strict liability application, strict product liabilityUnder strict product liability, manufacturers, distributors, and retailers are strictly liable for injuries caused by unreasonably dangerous products..

In strict product liability, any retailer, wholesaler, or manufacturer that sells an unreasonably dangerous product is strictly liable. For example, Toyota recently disclosed that it had manufactured and sold several vehicle models with faulty accelerators, leading to several cases of unintended acceleration and subsequent deaths. Vehicles that accelerate unintentionally are clearly unreasonably dangerous. In this case, the manufacturer (Toyota Japan), the wholesaler or importer (Toyota’s U.S. sales company), and the retailer (local dealers) are all strictly liable for injuries caused by these faulty accelerators. Note, however, that strict liability applies only to commercial sellers. If a private citizen sold his or her Toyota on Craigslist, for example, he or she would not be strictly liable for selling an unreasonably dangerous product.

To demonstrate that a product is unreasonably dangerous, plaintiffs have two theories available to them. First, they might allege that the product was defective because of a flaw in the manufacturing process. Under this theory, the vast majority of products being produced turn out fine, but due to some sort of production defect, a few samples or a batch turns out defective. If these defective samples are sold to the public, the manufacturer or seller is strictly liable. A light bulb factory that manufactures a million safe light bulbs, for example, and then manufacturers one that explodes when it is turned on due to some production defect, is strictly liable for the injuries caused. Similarly, a frozen pizza factory that produces thousands of pizzas without any trouble would be strictly liable if one frozen pizza is produced that contains foreign contaminants because of a production defect such as an inattentive worker or machine breakdown.

Second, a product may be defective because of a design defect. Here, there is nothing wrong with the manufacturing or production of the product. Rather, the product is defective because it was designed incorrectly or in a manner that causes the product to be unreasonably dangerous. Engineers continually work to design products to be as safe as possible, but in some cases the product is nonetheless dangerous, and the manufacturer or seller is strictly liable. For example, starting in 1991 several Boeing 737 jetliners began experiencing unexpected movement in the rudder, leading to several high-profile crashes including a USAir flight in Pittsburgh that killed 132 people.“When Jets Crash: How Boeing Fights to Limit Liability,” Seattle Times, October 30, 1996, http://seattletimes.nwsource.com/news/local/737/part04 (accessed September 27, 2010). During the course of investigation, the government discovered that the part that controls the rudder gets very cold in flight, and when it is injected with hot hydraulic fluid, the part can jam and move the rudder in the opposite direction of what the pilot is calling for. This design defect was eventually fixed by upgrading the rudder control systems on all existing Boeing 737s worldwide.

http://www.time.com/time/business/article/0,8599,128198,00.html

In 1999 Ford customers in the Middle East began experiencing tread separation problems on Ford Explorer SUVs. The tires would disintegrate, leading to a loss of control and often a rollover crash. The company initially believed that the problem was limited to the Middle East because of unique characteristics there such as extremely hot weather, lowered tire inflation pressures for driving in sand, and harsh operating environments. Soon, however, vehicles in the United States, especially in hotter regions of the country, began experiencing the same problems. The death toll mounted to over 170 deaths and over 700 injuries from these accidents. Ford’s investigation led the company to believe that certain fifteen-inch tires manufactured by Firestone were to blame; virtually all the accidents involved Firestone tires manufactured in one plant in Decatur, Illinois (now closed). Similar vehicles equipped with Goodyear tires rarely experienced tread separation problems. Firestone, on the other hand, blamed the Ford Explorer for being defectively designed. Firestone argued that the Explorer lacked critical safety features to lower the center of gravity, reduce the propensity to roll over, and lessen the chance of underinflating the tires. Firestone pointed out that the same tires did not experience any problems when installed on GM vehicles. Whether the fault lay with a production defect in Firestone tires or design defect in Ford Explorers, both companies were strictly liable. Ford spent over $3 billion recalling the tires and ended its one-hundred-year relationship with Firestone. Congress also responded, passing a federal law requiring all vehicles to be equipped with tire pressure monitoring systems.

Many product liability cases arise from the defective design theory because courts have held that the warning labels on products, as well as accompanying literature, are all part of a product’s design. A product that might be dangerous if used in a particular way, therefore, must have a warning label or other caution on it, so that consumers are aware of the risk posed by that product. Manufacturers must warn against a wide variety of possible dangers from using their products, as long as the injury is foreseeable. If consumer misuse is foreseeable, manufacturers must warn against that misuse as well. For these reasons, window blinds come with warnings about choking hazards posed by the rope used to raise and lower them, and hair dryers come with warnings about operating them in bathtubs and showers.

While you may think that these warnings are a little silly, keep in mind that products can harm or kill people who don’t know how to use them correctly. For example, in one case, a woman traveling in the passenger seat of a GM SUV was killed in a low-speed collision in a parking lot when airbags deployed in a collision. The woman was killed because her seat was reclined and rather than being restrained by the seat and seatbelt, she “submarined” underneath the seat belt and hit the deploying airbag. When her family sued GM, the company argued that seats and seatbelts work only when the seat is in an upright position and that the owner’s manual warns not to recline the seat when the vehicle is in motion. The family argued successfully that this warning was not clear and conspicuous enough, and that as a result many people travel with their seat reclined. Do you believe the lack of a clear and conspicuous warning about the danger of traveling with the seat reclined makes a vehicle’s design defective?

http://www.usatoday.com/life/people/2007-12-04-quaid-lawsuit_N.htm

Figure 7.9

Should these labels be more distinctive to prevent mistakes?

In November 2007 actor Dennis Quaid and his wife Kimberly were celebrating the birth of their newborn twins at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles. The twins suffered a staph infection, and doctors prescribed a blood thinner to prevent blood clots. The blood thinner, Heparin, comes in two doses, with the heavier dose one thousand times more potent than the lower dose. However, the two doses come in similar packaging with blue labels. Nurses at the hospital inadvertently gave the twins the higher dose, nearly killing the twins. In Indianapolis earlier that year, three premature infants did in fact die from overdosing on Heparin. The Quaids are suing the manufacturer, arguing that the labels on the drug represent a design defect because it is too easy to confuse the two doses. The manufacturer, Baxter Healthcare, has since changed the design to include a red warning label that must be torn off before the drug can be used.

There are several defenses to strict product liability. Since product liability is strict liability, the plaintiff’s contributory or comparative negligence is not a defense. However, assumption of risk can be a defense. As in negligence, the user must know of the risk of harm and voluntarily assume that risk. For example, someone cutting carrots with a sharp knife voluntarily assumes the risk that the knife may slip and cut him or her, meaning he or she cannot sue the knife manufacturer. However, if the knife blade unexpectedly detaches from the knife handle because of a design or production defect, and injures the user, then there is no assumption of risk since the user would not have known about that particular risk.

Product misuse is another defense to strict product liability. If the consumer misuses the product in a way that is unforeseeable by the manufacturer, then strict liability does not apply. Modifying a lawn mower to operate as a go-kart, for instance, is product misuse. Note that manufacturers are still liable for any misuse that is foreseeable, and they must take steps to warn against that misuse. A related defense is known as the commonly known danger doctrine. If a manufacturer can convince a jury that the plaintiff’s injury resulted from a commonly known danger, then the defendant may escape liability.

In areas where strict liability applies, the defendant is liable no matter how careful the defendant was in preventing harm. Carrying out ultrahazardous activities results in strict liability for defendants. Another area where strict liability applies is in the serving of alcohol to minors or visibly intoxicated persons. A large area of strict liability applies to the manufacture, distribution, and sale of unreasonably dangerous products. Products can be unreasonably dangerous because of a production defect, design defect, or both. A product’s warnings and documentation are a part of a product’s design, and therefore inadequate warnings can be a basis for strict product liability. Assumption of risk, product misuse, and commonly known dangers are all defenses to strict product liability.

Tort law is continually changing and adapting to societal expectations about the freedoms and interests we expect to protect. Although it has endured for many years, recent debates have sought to recast the viability of tort law in political terms. The Republican Party platform, for example, maintains that the rule of tort trial lawyers threatens America’s “global competitiveness, denies Americans access to the quality of justice they deserve, and puts every small business one lawsuit away from bankruptcy.”Republican National Committee, “2008 Republican Platform,” 2008, http://www.gop.com/2008Platform/Economy.htm#7 (accessed September 27, 2010). Many businesses see tort lawsuits as a nuisance at best and ruinous at worst, and would like to see them disappear altogether. Consumer rights activists, on the other hand (and often backed by plaintiff lawyer groups), believe that tort lawsuits are the most effective way to keep corporations honest and prevent them from putting profits before safety. This debate has led to several proposals for tort reform among the various states, or by the federal government.

These reforms can take several different forms. One common reform is to impose a statute of repose on product liability claims. These statutes function like a statute of limitations and bar plaintiffs from filing tort claims after a certain period of time has lapsed. For example, in 1994 President Clinton signed the General Aviation Revitalization Act into law, imposing an eighteen-year statute of repose on product liability claims brought against general aviation aircraft manufacturers such as Cessna and Piper. The law allowed these manufacturers to once again launch new light aircraft production in the United States. Another popular tort reform is a cap on punitive damages. President George W. Bush supported a nationwide punitive damage cap of $250,000 for medical malpractice claims, but Congress did not pass any such law. Other reforms call for eliminating defective design as a basis for recovery, barring any claims if a product has been modified by the consumer in any way, and allowing for the state-of-the-art defense (if something was “state of the art” at the time it was produced then no strict liability can apply).

Occasionally Congress passes legislation that provides industry-wide tort lawsuit protection for certain industries. For example, in 2005 President George W. Bush signed the Protection of Lawful Commerce in Arms Act. The law shields firearm manufacturers and dealers from product liability lawsuits for crimes committed with their products. Many industries have tried to obtain this form of industry-wide protection, either from Congress or from judicial rulings. Most recently, drug manufacturers hoped for industry-wide protection by arguing that if the Food and Drug Administration approved drug labels, labeling lawsuits would be preempted by the Constitution. The Supreme Court rejected this argument in 2009.Wyeth v. Levine, 555 U.S. ___ (2009), http://www.law.cornell.edu/supct/html/06-1249.ZS.html (accessed October 2, 2010).

In spite of these efforts at tort reform, torts remain an important and viable part of civil law. All businesses, of all sizes and across all industries, must maintain a keen understanding of the duties and responsibilities imposed by tort law. Being able to understand, and even embrace, these duties can help businesses thrive while keeping consumers and customers safe.