Businesses must be organized in order to effectively conduct their operations. This organization can run from simple to complex and depends greatly on the needs of the business owners to structure their liability and taxes. In this chapter, you’ll learn about the factors that go into organizing a business. Specifically, you should be able to answer the following questions:

Figure 11.1 Apple’s Headquarters in Cupertino, California

Source: Photo courtesy of kalleboo, http://www.flickr.com/photos/kalleboo/3614939469/sizes/o.

Many of you may be reading this chapter on a laptop or desktop designed and manufactured by Apple Inc. You may own a phone from Apple, or perhaps a portable music device. The company’s innovation, product development process, marketing capabilities in creating new and unthought-of markets, and ability to financially reward its owners are well known. While you might enjoy Apple products as a consumer, have you ever thought about Apple as a corporationA legal entity chartered by the state, with a separate and distinct existence from its owners.? Its corporate headquarters in Cupertino, California (Figure 11.1 "Apple’s Headquarters in Cupertino, California"), is the physical embodiment of this entity we call a corporation, but what does that mean? It might surprise you to learn that this building, or rather the legal concept of the entity that occupies it, is more like you than you realize. For example, just like you, this entity can own property. This entity can enter into contracts to buy and sell goods. This entity can hire and fire employees. This entity can open bank accounts and engage in complex financial transactions. This entity can sue others, and can be sued in court. This entity even has constitutional rights, just like you. Unlike you, however, this entity does not breathe, does not bleed, and in fact may be immortal. And most unlike you, this entity has no independent judgment of its own, no moral compass or conscience to tell it the difference between right and wrong. In this chapter we’ll explore corporate entities such as Apple Inc. in detail. We’ll examine why human beings choose to organize into corporate entities in the first place, and why the law recognizes these entities for public policy purposes. We’ll start by looking at the factors that go into making a decision about entity choice, and then examine the available choices in detail.

Try to recall the basic function of a businessAny commercial enterprise, usually organized for profit of its owners, and typically involving the provision of goods or services to a customer.. At its most fundamental level, a business exists to make a profit for its owners. In a capitalist market-driven economy, a business that fails to make a profit ultimately ceases to exist, overtaken by creditorsPersons or entities to whom money is owed. and competitors. The need to make a profit is one truism that binds all businesses together, but beyond that, it’s hard to draw generalizations about business operations. The world of business is as varied as human experience itself, ranging from the neighborhood kids who shovel snow in the winter and sell lemonade in the summer, to the neighborhood pizza restaurant, to the small tool-and-die factory on the outskirts of town making machine tools, to the multinational corporation with hundreds of thousands of employees scattered throughout the globe. Some businesses make things in factories (manufacturers), other businesses sell things that other businesses make (retailers or franchiseesPersons or entities granted a franchise to market or sell a the franchisor’s goods or services, usually under a franchise agreement.), and still other businesses exist to help both the makers and sellers make and sell better (business consultants). Some businesses don’t make things at all, and instead profit by selling their services (think of an accounting or law firm, a house painting company, or a hotel) or by lending money at a higher rate of interest than it can borrow.

With this breadth and diversity, it’s not surprising that there is no “one size fits all” approach to choosing a business organization. When choosing what form of entity is best, business professionals must consider several factors. First, they have to consider how much it costs to create the entity and how hard it is to create. Some entities are easy to create, while others are more complicated and have ongoing maintenance requirements that are important to consider. Second, they have to consider how easy it is for the business to continue if the founder dies, decides to retire, or decides to enter a new business altogether. Third, they have to consider how difficult it might be to raise money to grow or expand the business. Fourth, they have to consider what sort of managerial control they wish to keep on the business, and whether they are willing to cede control to outsiders. Fifth, they have to consider whether or not they wish to eventually expand ownership to members of the public. Sixth, they must give some thought to tax planning to minimize the taxes paid on earnings and income. Finally, and most importantly, they have to consider whether or not they wish to protect their personal assets from claims, a feature known as limited liabilityAny type of investment where the investor’s maximum possible losses is the amount invested. The investor’s other assets are not reachable by creditors..

It’s important to remember that choosing a business organization is different from what kind of business you run. For example, some businesses are known as franchises because they operate under a license agreement (contract) whereby they agree to follow certain standards set by the franchisor, purchase their goods from the franchisor, and maybe share either a royalty fee or percentage of profits with the franchisor. Franchises are a very common type of business (especially in the food and services industries), but there is no typical form of business for a franchise. Depending on the needs of the franchise owners, a franchise could be a sole proprietorship, a limited liability company (LLC), or a corporation. Similarly, we sometimes refer to “nonprofit organizations” such as universities or charities as separate legal entities. Although they are nonprofit, some of these enterprises can be very large, with complex operations that spread across borders (for example, the Red Cross or Doctors Without Borders). For tax purposes, nonprofits do not have to pay any taxes if they meet strict qualifications under IRS guidelines to become a “501(c)(3)” organization (named for the section of the Internal Revenue Code that grants nonprofit status), but from a legal perspective, these entities can also take on any number of forms, from sole proprietorships to corporations.

If you are ever in a position to start a new business venture, your focus is typically on growing revenue and cutting costs so that you can maximize profit. You may not be very concerned with entity choice at the outset, since so many other considerations are competing for your attention. Once an entity choice is made, however, it is difficult (but not impossible) to change to another selection. Since entity choice can have a profound effect on these considerations, it is important to gain a basic understanding of the available choices so that you, the business professional, can focus on the business fundamentals rather than legal or accounting details.

Business organizations are an important part of a business’s structure. Different organizations provide different advantages and disadvantages in creation cost and simplicity, ongoing maintenance requirements, dissolution and continuity, fundraising, managerial control, public ownership, tax planning, and limited liability. The type of business being conducted (for-profit, nonprofit, franchise) has little to do with the business organization in which the business is conducted. Many business organizations take the form of separate legal entities, which the law recognizes as nearly like persons for purposes of legal rights.

Lily, a college sophomore, is home for the summer. Unable to find even part-time work in a tough economy, she begins to help her parents by cleaning up their overgrown garden. After a few days of this work, Lily discovers that she enjoys doing this and is good at it. The neighbors see the work Lily is doing, and they ask her to help their gardens too. Within a week, Lily has scheduled appointments and jobs throughout the neighborhood. Using the money she has earned, she places orders for additional landscaping equipment and materials with a local retailer. Within a month, she is so busy that she has to hire workers to do some of the more routine tasks, such as mulching and lawn mowing, for her. By the middle of summer, Lily has applied knowledge she picked up in her business classes by developing a name for her business (Lily’s Landscaping) and developing marketing materials such as a Facebook fan page, flyers to be posted at local stores, business cards, and a YouTube video showing her projects. By the end of the summer, Lily has earned a healthy profit for all her work and developed valuable know-how on how to run her business. She has to stop working when the weather gets cooler and she returns to school, but promises herself to restart the business next summer.

Lily is a sole proprietorA type of business where there is no legal distinction between the business and its owner., the most common form of doing business in the United States. From a legal perspective, there is absolutely no difference between Lily and Lily’s Landscaping—they are one and the same, and completely interchangeable with each other. If Lily’s Landscaping makes a profit, that money belongs exclusively to Lily. If Lily’s Landscaping needs to pay a bill to a supplier or creditor, and Lily’s Landscaping doesn’t have the money, then Lily has to pay the bill. When Lily’s Landscaping enters into a contract to plant a new flower garden, it is actually Lily that is entering into the contract. If Lily’s Landscaping wants to open a bank account to accept customer payments or to pay bills, then Lily will actually own the account. When Lily’s Landscaping enters into a contract promising to pay a worker to mow lawns or lay mulch, it is actually Lily that is entering into that contract. Lily can even apply for a “doing business as” or d.b.a. filing in her state, so that her business can carry on under the fictitious name “Lily’s Landscaping.” Note, however, that legally Lily’s Landscaping is still no different from Lily herself. Any fictitious name therefore cannot have any words in it that suggest a separate entity, such as “Corp.” or “Inc.”

http://www.business.gov/register/business-name/dba.html

The legal name for a sole proprietorship is the owner’s name. Some business owners are happy to use their own names for their business, but for marketing and branding reasons many business owners prefer to use a fictitious name. Using a fictitious name is permitted under state laws where the business operates, using a filing known as a d.b.a. filing. Explore this Web site to find out how to file a d.b.a. filing in your state.

There are many advantages to doing business as a sole proprietor, advantages that make this form of doing business extremely popular. First, it’s easy to create a sole proprietorship. In effect, there is no creation cost or time, since there is nothing to create. The entrepreneurA person who organizes a business and carries the risk of loss and reward of profit with it. in charge of the business simply starts doing business, charging money, and providing goods or services. Depending on the business, some sole proprietors may need to obtain permits or licenses before they can begin operating. A pizza restaurant, for example, may need to obtain a food service license, while a bar or tavern may need to obtain a liquor license. A small grocery store may need a license to collect sales tax. Do not confuse these governmental permits with legal approval for a business organization; in a sole proprietorship, the license is granted to the individual owner.

Another key advantage to sole proprietorships is autonomy. Since the owner is the business, Lily can decide for herself what she wants to do to Lily’s Landscaping. She could set her own hours, grow as quickly or slowly as she wants, expand into new lines of businesses, take a vacation, or wind down the business, all at her own whim and direction. That autonomy also comes with total ownership of the business’s finances. All the money that Lily’s Landscaping takes in, even if it is in a separate bank account, belongs to Lily, and she can do with that money whatever she wants.

These advantages must be weighed against some very important disadvantages. First, since a sole proprietorship can have only one owner, it is impossible to bring in others to the business. Lily cannot bring in her college roommate to work on Web site design as a partner in the business, for example. In addition, since the business and the owner are identical, it is impossible to pass on the business from Lily. If Lily dies, the business dies with her. Of course, she can always sell or give away the business assets (equipment, inventory, as well as intangible assets such as customer lists and goodwill).

Raising working capital can be a problem for sole proprietors, especially those early in their business ventures. Many entrepreneurial ventures are built on great ideas but need capital to flourish and develop. If the entrepreneur lacks individual wealth, then he or she must seek those funds from other sources. For example, if Lily decides to expand her business and asks her wealthy uncle to invest money in Lily’s Landscaping, there is no way for her uncle to participate as a profit-sharing owner in the business. He can make a loan to her, or enter into a profit-sharing contract with her, but there is no way for him to own any part of Lily’s Landscaping. Traditionally, most sole proprietors seek funding from banks. Banks approach these loans just like any other personal loan to an individual, such as a car loan or mortgage. Down payment requirements may be high, and typically the banks require some form of personal collateral to guarantee the loan, even though the loan is to be used to grow the business. Many sole proprietors resort to running their personal credit cards to the maximum limit, or transferring balances between credit cards, in the early stage of their business.

http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=113816657

During the Great Recession, many banks faced a liquidity crisis as loans they made performed poorly. Lending tightened, interest rates went up, credit lines went down, and standards became higher. The effect on many sole proprietors, including those featured in this National Public Radio story, has been very challenging.

In certain industries, entrepreneurs may be able to find financing through venture capitalMoney invested in an unproven or new start-up business.. Venture capital firms combine funds from institutional investors and high net-worth individuals (known as angel investorsAffluent individuals (or groups of individuals) who provide capital to start-up and early-stage businesses.) to identify promising start-ups, and to fund them in a private placementA nonpublic offering in which a business sells securities to a few chosen and qualified investors to raise capital. offering until the start-up has developed its technology to a commercially feasible stage. At that point the venture capital firm seeks an exit strategy, typically through offering sale of the business to the public in an initial public offering (IPO)The first time a corporation sells its shares to members of the public..

Tax planning can also be challenging for the sole proprietor. Since there is no legal distinction between the owner and the business, all the income generated by the business is treated as ordinary personal income to the owner. The United States has several income tax rates depending on the type of income being taxed, and ordinary personal income typically suffers the highest rate of taxation. Being able to plan effectively to take advantage of lower income tax rates is very difficult for the sole proprietor.

Finally, sole proprietors suffer from one hugely unattractive feature: unlimited liabilityAn undesirable situation where if the debts of the business exceed its ability to pay, creditors may reach the personal assets of the business owners.. Since there is no difference between the owner and the business, the owner is personally liable for all the business’s debts and obligations. For example, let’s say that Lily’s Landscaping runs into some financial trouble and is unable to generate planned revenue in a given month due to unexpectedly bad weather. Creditors of the business include landscaping supply stores, employees, and outside contractors such as the company that prints business cards and maintains the business Web site. Lily is personally liable to pay these bills, and if she doesn’t she can be sued for breach of contract. Some proprietors are very successful and can generate many hundreds of thousands of dollars in profit every year. Unlimited liability puts all the personal assets of the sole proprietor reachable by creditors. Personal homes, automobiles, boats, bank accounts, retirement accounts, and college funds—all are within reach of creditors. With unlimited liability, all it takes is one successful personal injury lawsuit, not covered by insurance or exceeding insurance limits, to wipe out years of hard work by an individual business owner.

For these reasons, while sole proprietors are still the most common way of doing business in the United States, they are in many ways the most unattractive. Thankfully, modern business law creates real and viable alternatives for sole proprietors, as we’ll discuss shortly.

Sole proprietorships are the most common way of doing business in the United States. Legally, there is no difference or distinction between the owner and the business. The legal name of the business is the owner’s name, but owners may carry on business operations under a fictitious name by filing a d.b.a. filing. Sole proprietors enjoy ease of start-up, autonomy, and flexibility in managing their business operations. On the downside, they have to pay ordinary income tax on their business profits, cannot bring in partners, may have a hard time raising working capital, and have unlimited liability for business debts.

Let’s assume that after her first summer running Lily’s Landscaping, Lily decides that it’s time to take her business to the next level. She has gathered a lot of expertise in running the operations in her business, from placing orders with suppliers to scheduling workers for client projects. She realizes, however, that she’s not very good at marketing or accounting, and that if her business is to grow, she needs to bring someone on board who can create a strong brand and strategy for growth, as well as keep good records of her accounts so that she can plan for the future. Fortunately, her good friend Adam is a double major in accounting and marketing, and after a series of discussions, Adam and Lily decide to run Lily’s Landscaping together.

Lily and Adam have formed a general partnershipAssociation of two or more persons in an unincorporated entity to do business and share profits and losses.. The moment they agreed to run Lily’s Landscaping together, and to share in the profits and losses of the business together, the partnership was formed. Although they formed their partnership verbally, most general partnerships are formed formally, with partners writing down their agreement in a special type of contract known as the articles of partnershipAlso known as a partnership agreement, a voluntary contract (typically written) in which two or more persons decide to conduct business together and share profits and losses.. The articles can set forth anything the partners wish to include about how the partnership will be run. Normally, all general partners have an equal voice in management, but as a creation of contract, the partners can modify this if they wish. As in a sole proprietorship, there is no state involvement in creating a general partnership because there is no separation from the business and the partners—they are legally the same.

General partnerships are dissolved as easily as they are formed. Since the central feature of a general partnership is an agreement to share profits and losses, once that agreement ends, the general partnership ends with it. In a general partnership with more than two persons, the remaining partners can reconstitute the partnership if they wish, without the old partner. A common issue that arises in this situation is how to value the withdrawing partner’s share of the business. Articles of partnership therefore typically include a buy/sell agreementAn agreement between partners to value and sell a partner’s portion of the business in the event the partner withdraws or dies., setting forth the agreement of the partners on how to account for a withdrawing partner’s share, which the remaining partners then agree to pay to the withdrawing partner (or the spouse or heir if the partner dies).

http://www.law.cornell.edu/nyctap/I96_0191.htm

After a nearly twenty-year career, Evan Dawson was a partner at a major New York City law firm, White & Case. In 1988 the firm tried to persuade him to withdraw as a partner, but he refused. In July 1988 the other partners in the firm voted to dissolve the partnership and then immediately re-formed again, without Dawson as a partner. He had effectively been fired as a partner from a general partnership. Dawson filed a suit against White & Case for an “accounting,” claiming that the “goodwill” of the law firm should be part of the valuation of the partnership. The common law in New York at the time was that professional partnerships like law firms have no goodwill. The reasoning behind the rule is that as professionals, law firm partners develop and cultivate their own goodwill with clients, and if a partner leaves the firm then the goodwill leaves with that partner. The New York Court of Appeals, in its opinion on this case, held that unless the partnership agreement states otherwise, goodwill is indeed an asset of the partnership and has to be distributed when the partnership is dissolved.

A general partnership is taxed just like a sole proprietorship. The partnership is considered a disregarded entityFor tax purposes, an entity that does not need to file its own tax return or pay taxes; profits and losses flow through disregarded entities to the owners. for tax purposes, so income “flows through” the business to the partners, who then pay ordinary income tax on the business income. The partnership may file an information returnTax return that provides information only to the taxing authority., reporting total income and losses for the partnership, and how those profits and losses are allocated among the general partners. As is the case for sole proprietors, tax planning opportunities are limited for general partners.

General partnerships are also similar to sole proprietorships in unlimited liability. Every partner in the partnership is jointly and severally liableA form of liability where creditors or other claimants can pursue their entire claim against one, several, or all possible defendants, leaving defendants to sort out their respective proportions of liability and payment. for the partnership’s debts and obligations. This is a very unattractive feature of general partnerships. One partner may be completely innocent of any wrongdoing and still be liable for another partner’s malpractice or bad acts.

Let’s assume that the general partnership formed by Lily and Adam flourishes and becomes profitable. To grow the landscaping business, they want to bring in Lily’s wealthy uncle as a partner. The uncle, however, is worried about maintaining limited liability. In most states, they can form a limited partnershipA form of partnership formed in compliance with state law that provides limited liability to certain limited partners who agree to refrain from management of the business.. A limited partnership has both general partners and limited partners. In this case, Lily and Adam will remain as general partners in the business, but the uncle can become a limited partnerA partner in a limited partnership given limited liability. and enjoy limited liability. As a limited partner, the most he can lose is the amount of his investment into the business, nothing more. Limited partnerships have to be formed in compliance with state law, and limited partners are generally prohibited from participating in day-to-day management of the business.

A general partnership is formed when two or more persons agree to share profits and losses in a joint business venture. A general partnership is not a separate legal entity, and partners are jointly and severally liable for the partnership’s debts, including acts of malpractice by other partners. Income from a general partnership flows through to the partners, who pay tax at the ordinary personal income tax rate. In most states general partners can also bring in limited partners, creating a limited partnership. Limited partnerships must be formed in compliance with state statutes. Limited partners enjoy limited liability but generally cannot participate in day-to-day management of the business.

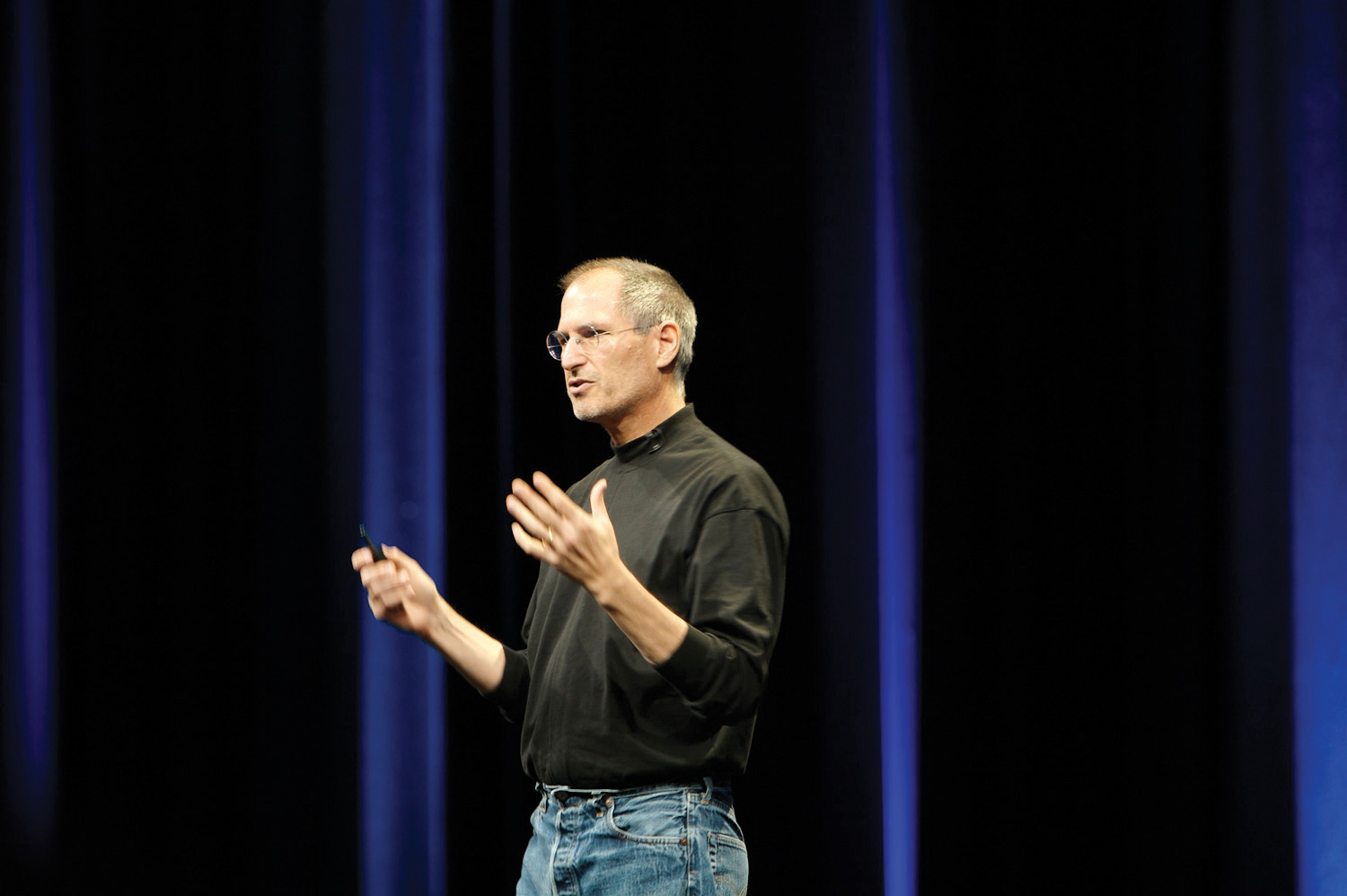

Figure 11.4 Apple Cofounder Steve Jobs

Source: Photo courtesy of acaben, http://www.flickr.com/photos/acaben/541334636/sizes/o.

So far in this chapter, we have explored sole proprietorships and partnerships, two common and relatively painless ways for persons to conduct business operations. Both these forms of business come with significant disadvantages, however, especially in the area of liability. The idea that personal assets may be placed at risk by business debts and obligations is rightfully scary to most people. Businesses therefore need a form of business organization that provides limited liability to owners and is also flexible and easy to manage. That is where the modern corporationA legal entity chartered by the state, with a separate and distinct existence from its owners. comes in.

Consider, for example, tech entrepreneur and Apple cofounder Steve Jobs (Figure 11.4 "Apple Cofounder Steve Jobs"). As a young man, he was a college dropout without much ability for computer engineering. If doing business as a sole proprietor was his only option, Apple would not exist today. However, Jobs met a talented computer engineer named Steve Wozniak, and the two decided to pool their talents to form Apple Computer in1976. A year later, the company was incorporatedOrganized and created into a legal corporation. and in 1980 went public in an initial public offering (IPO)The first time a corporation sells its shares to members of the public.. Incorporation allowed Jobs much more flexibility in carrying out business operations than a mere sole proprietorship could. It allowed him to bring in other individuals with distinct skills and capabilities, raise money in the early stage of operations by promising shares in the new company, and eventually become very wealthy by selling stockCapital raised by a corporation through issuance of shares entitling owners to an ownership interest., or securitiesAny negotiable instruments representing financial value, such as a bond or stock., in the company.

http://cnettv.cnet.com/60-minutes-steve-jobs/9742-1_53-50004696.html

Sole proprietorships are limiting not just in a legal sense but also in a business sense. As Steve Jobs points out in this video, great things in business are never accomplished with just one person; they are accomplished with a team of people. While Jobs may have had the vision to found Apple Inc. and maintains overall strategic leadership for the company, the products the company releases today are very much the result of the corporation, not any single individual.

Unlike a sole proprietorship or general partnership, a corporation is a separate legal entity, separate and distinct from its owners. It can be created for a limited duration, or it can have perpetual existence. Since it is a separate legal entity, a corporation has continuity regardless of its owners. Entrepreneurs who are now dead founded many modern companies, and their companies are still thriving. Similarly, in a publicly traded company, the identity of shareholders can change many times per hour, but the corporation as a separate entity is undisturbed by these changes and continues its business operations.

Since corporations have a separate legal existence and have many legal and constitutional rights, they must be formed in compliance with corporate law. Corporate law is state law, and corporations are incorporated by the states; there is no such thing as a “U.S. corporation.” Most corporations incorporate where their principal place of business is located, but not all do. Many companies choose to incorporate in the tiny state of Delaware even though they have no business presence there, not even an office cubicle. Delaware chanceryA court with jurisdiction to decide cases based on equity as well as law. courts have developed a reputation for fairly and quickly applying a very well-developed body of corporate law in Delaware. The courts also operate without a jury, meaning that disputes heard in Delaware courts are usually predictable and transparent, with well-written opinions explaining how the judges came to their conclusions.

http://www.business.gov/register/incorporation

Since corporations are created, or chartered, under state law, business founders must apply to their respective state agencies to start their companies. These agencies are typically located within the Secretary of State. Click the link to explore how to fill out the forms for your state to start a company. You may be surprised at how quickly, easily, and inexpensively you can form your own company! Don’t forget that your company name must not be the same as another company’s name. (Most states allow you to do a name search first to ensure that name is available.)

To start a corporation, the corporate founders must file the articles of incorporationA legal document that creates a corporation when filed and approved by the relevant state authority. with the state agency charged with managing business entities. These articles of incorporation may vary from state to state but typically include a common set of questions. First, the founders must state the name of the company and whether the company is for-profit or nonprofit. The name has to be unique and distinctive, and must typically include some form of the words “Incorporated,” “Company,” “Corporation,” or “Limited.” The founders must state their identity, how long they wish the company to exist, and the company’s purpose. Under older common law, shareholders could sue a company that conducted business beyond the scope of its articles (these actions are called ultra viresAn act in excess of designated legal power.), but most modern statutes permit the articles to simply state the corporation can carry out “any lawful actions,” effectively rendering ultra vires lawsuits obsolete in the United States. The founders must also state how many sharesUnits of account for a financial instrument, such as stocks. the corporation will issue initially, and the par valueThe face vale of a security as determined by the corporation. Par value has no relation to market value. of those shares. (Of course, the company can issue more shares in the future or buy them back from shareholders.)

Unlike sole proprietorships, corporations can be quite complicated to manage and typically require attorneys and accountants to maintain corporate books in good order. In addition to the foundation requirements, corporate law requires ongoing annual maintenance of corporations. In addition to filing fees due at the time of incorporation, there are typically annual license fees, franchise fees and taxes, attorney fees, and fees related to maintaining minute books, corporate seals, stock certificates and registries, as well as out-of-state registration. A domestic corporationA corporation operating in the state in which it was incorporated. is entitled to operate in its state of incorporation but must register as a foreign corporationA corporation incorporated in a state other than where it is seeking to operate. to do business out of state. Imagine filing as a foreign corporation in all fifty states, and you can see why maintaining corporations can become expensive and unwieldy.

Owners of companies are called shareholdersOwners of a corporation.. Corporations can have as few as one shareholder or as many as millions of shareholders, and those shareholders can hold as few as one share or as many as millions of shares. In a closely held corporationA corporation whose stock is held by only a small number of shareholders., the number of shareholders tends to be small, while in a publicly traded corporation, the body of shareholders tends to be large. In a publicly traded corporation, the value of a share is determined by the laws of supply and demand, with various markets or exchanges providing trading space for buyers and sellers of certain shares to be traded. It’s important to note that shareholders own the share or stock in the company but have no legal right to the company’s assets whatsoever. As a separate legal entity, the company owns the property.

Shareholders of a corporation enjoy limited liability. The most they can lose is the amount of their investment, whatever amount they paid for the shares of the company. If a company is unable to pay its debts or obligations, it may seek protection from creditors in bankruptcy court, in which case shareholders lose the value of their stock. Shareholders’ personal assets, however, such as their own homes or bank accounts, are not reachable by those creditors.

Shareholders can be human beings or can be other corporate entities, such as partnerships or corporations. If one corporation owns all the stock of another corporation, the owner is said to be a parent company, while the company being owned is a wholly owned subsidiaryA company wholly owned or controlled by another company.. A parent company that doesn’t own all the stock of another company might call that other company an affiliateA commercial enterprise with some sort of contractual or equity relationship with another commercial enterprise. instead of a subsidiary. Many times, large corporations may form subsidiaries for specific purposes, so that the parent company can have limited liability or advantageous tax treatment. For example, large companies may form subsidiaries to hold real property so that premises liabilityThe liability of landowners and leaseholders for torts that occur on their real property. is limited to that real estate subsidiary only, shielding the parent company and its assets from tort lawsuits. Companies that deal in a lot of intellectual property may form subsidiaries to hold their intellectual property, which is then licensed back to the parent company so that the parent company can deduct royalty payments for those licenses from its taxes. This type of sophisticated liability and tax planning makes the corporate form very attractive for larger business in the United States.

Corporate law is very flexible in the United States and can lead to creative solutions to business problems. Take, for example, the case of General Motors Corporation. General Motors Corporation was a well-known American company that built a global automotive empire that reached virtually every corner of the world. In 2009 the General Motors Corporation faced an unprecedented threat from a collapsing auto market and a dramatic recession, and could no longer pay its suppliers and other creditors. The U.S. government agreed to inject funds into the operation but wanted the company to restructure its balance sheet at the same time so that those funds could one day be repaid to taxpayers. The solution? Form a new company, General Motors Company, the “new GM.” The old GM was brought into bankruptcy court, where a judge permitted the wholesale cancellations of many key contracts with suppliers, dealers, and employees that were costing GM a lot of money. Stock in the old GM became worthless. The old GM transferred all of GM’s best assets to new GM, including the surviving brands of Cadillac, Chevrolet, Buick, and GMC; the plants and assets those brands rely on; and the shares in domestic and foreign subsidiaries that new GM wanted to keep. Old GM (subsequently renamed as “Motors Liquidation Company”) kept all the liabilities that no one wanted, including obsolete assets such as shuttered plants, as well as unpaid claims from creditors. The U.S. federal government became the majority shareholder of General Motors Company, and may one day recoup its investment after shares of General Motors Company are sold to the public. To the public, there is very little difference in the old and new GM. From a legal perspective, however, they are totally separate and distinct from each other.

One exception to the rule of limited liability arises in certain cases mainly involving closely held corporations. Many sole proprietors incorporate their businesses to gain limited liability but fail to realize when they do so that they are creating a separate legal entity that must be respected as such. If sole proprietors fail to respect the legal corporation with an arm’s-length transactionA transaction made by parties as if they were unrelated, in a free market system, each acting in its own best interest., then creditors can ask a court to pierce the corporate veilAn equitable doctrine allowing creditors to petition a court to not permit limited liability to a corporate shareholder.. If a court agrees, then limited liability disappears and those creditors can reach the shareholder’s personal assets. Essentially, creditors are arguing that the corporate form is a sham to create limited liability and that the shareholder and the corporation are indistinguishable from each other, just like a sole proprietorship. For example, if a business owner incorporates the business and then opens a bank account in the business name, the funds in that account must be used for business purposes only. If the business owner routinely “dips into” the bank account to fund personal expenses, then an argument for piercing the corporate veil can be easily made.

Not all shareholders in a corporation are necessarily equal. U.S. corporate law allows for the creation of different types, or classes, of shareholders. Shareholders in different classes may be given preferential treatment when it comes to corporate actions such as paying dividends or voting at shareholder meetings. For example, founders of a corporation may reserve a special class of stock for themselves with preemptive rightsSometimes known as rights of first refusal, rights given to existing shareholders in a corporation to purchase any newly issued stock to maintain same proportion of their existing holdings.. These rights give the shareholders the right of first refusal if the company decides to issue more stock in the future, so that the shareholders maintain the same percentage ownership of the company and thus preventing dilutionThe result when a corporation issues additional shares, resulting in a reduction of percentage of the corporation owned by shareholders. of their stock.

A good example of different classes of shareholders is in Ford Motor Company stock. The global automaker has hundreds of thousands of shareholders, but issues two types of stock: Class A for members of the public and Class B for members of the Ford family. By proportion, Class B stock is far outnumbered by Class A stock, representing less than 10 percent of the total issued stock of the company. However, Class B stock is given 40 percent voting rights at any shareholder meeting, effectively allowing holders of Class B stock (the Ford family) to block any shareholder resolution that requires two-thirds approval to pass. In other words, by creating two classes of shareholders, the Ford family continues to have a strong and decisive voice on the future direction of the company even though it is a publicly traded company.

Shareholder rights are generally outlined in a company’s articles of incorporation or bylawsRules and regulations adopted by a corporation for its own internal goverance.. Some of these rights may include the right to obtain a dividend, but only if the board of directorsA group of persons elected by shareholders of company to set high-level strategy for the company. approves one. They may also include the right to vote in shareholder meetings, typically held annually. It is common in large companies with thousands of shareholders for shareholders to not attend these meetings and instead cast their votes on shareholder resolutions through the use of a proxyA person authorized to act on behalf of a shareholder at a shareholders’ meeting..

Under most state laws, including Delaware’s business laws, shareholders are also given a unique right to sue a third party on behalf of the corporation. This is called a shareholder derivative lawsuitA lawsuit brought by a shareholder on behalf of a corporation against a third party. (so called because the shareholder is suing on behalf of the corporation, having “derived” that right by virtue of being a shareholder). In essence, a shareholder is alleging in a derivative lawsuit that the people who are ordinarily charged with acting in the corporation’s best interests (the officers and directors) are failing to do so, and therefore the shareholder must step in to protect the corporation. These lawsuits are very controversial because they are typically litigated by plaintiffs’ lawyers working on contingency fees and can be very expensive for the corporation to litigate. Executives also disfavor them because oftentimes, shareholders sue the corporate officers or directors themselves for failing to act in the company’s best interest.

One of the most important functions for shareholders is to elect the board of directors for a corporation. Shareholders always elect a director; there is no other way to become a director. The board is responsible for making major decisions that affect a corporation, such as declaring and paying a corporate dividendA portion of a corporation’s net income designated by the board of directors and returned to shareholders on a per share basis. to shareholders; authorizing major new decisions such as a new plant or factory or entry into a new foreign market; appointing and removing corporate officers; determining employee compensation, especially bonus and incentive plans; and issuing new shares and corporate bondsA debt obligation issued by corporations to raise money without selling stock.. Since the board doesn’t meet that often, the board can delegate these tasks to committees, which then report to the board during board meetings.

Shareholders can elect anyone they want to a board of directors, up to the number of authorized board members as set forth in the corporate documents. Most large corporations have board members drawn from both inside and outside the company. Outside board members can be drawn from other private companies (but not competitors), former government officials, or academe. It’s not unusual for the chief executive officer (CEO) of the company to also serve as chair of the board of directors, although the recent trend has been toward appointing different persons to these functions. Many shareholders now actively vie for at least one board seat to represent the interests of shareholders, and some corporations with large labor forces reserve a board seat for a union representative.

Board members are given wide latitude to make business decisions that they believe are in the best interest of the company. Under the business judgment ruleA legal assumption that prevents courts or juries from second-guessing decisions made by directors, unless they are proven to act with bad faith or corrupt motive., board members are generally immune from second-guessing for their decisions as long as they act in good faith and in the corporation’s best interests. Board members owe a fiduciary duty to the corporation and its shareholders, and therefore are presumed to be using their best business judgment when making decisions for the company.

Shareholders in derivative litigation can overcome the business judgment rule, however. Another fallout from recent corporate scandals has been increased attention to board members and holding them accountable for actually managing the corporation. For example, when WorldCom fell into bankruptcy as a result of profligate spending by its chief executive, board members were accused of negligently allowing the CEO to plunder corporate funds. Corporations pay for insurance for board members (known as D&O insuranceAlso known as Directors and Officers Liability Insurance, insurance that protects board members and senior officers of corporations from liability arising from their actions. D&O insurance is usually paid by the corporation., for directors and officers), but in some cases D&O insurance doesn’t apply, leaving board members to pay directly out of their own pockets when they are sued. In 2005 ten former outside directors for WorldCom agreed to pay $18 million out of their own pockets to settle shareholder lawsuits.

One critical function for boards of directors is to appoint corporate officersSenior management, often “C-Level,” or “Chief Level,” appointed by the board of directors of a corporation to execute strategy and manage day-to-day matters for the corporation.. These officers are also known as “C-level” executives and typically hold titles such as chief executive officer, chief operating officer, chief of staff, chief marketing officer, and so on. Officers are involved in everyday decision making for the company and implementing the board’s strategy into action. As officers of the company, they have legal authority to sign contracts on behalf of the corporation, binding the corporation to legal obligations. Officers are employees of the company and work full-time for the company, but can be removed by the board, typically without cause.

In addition to being somewhat cumbersome to manage, corporations possess one very unattractive feature for business owners: double taxationThe imposition of two or more separate taxes on the same pool of money.. Since corporations are separate legal entities, taxing authorities consider them as taxable persons, just like ordinary human beings. A corporation doesn’t have a Social Security number, but it does have an Employer Identification Numbers (EIN)A unique nine-digit number issued by the IRS to business entities for purposes of identification., which serves the same purpose of identifying the company to tax authorities. As a separate legal entity, corporations must pay federal, state, and local tax on net income (although the effective tax rate for most U.S. corporations is much lower than the top 35 percent income tax rate). That same pile of profit is then subject to tax again when it is returned to shareholders as a dividend, in the form of a dividend taxAn income tax on dividend payments to shareholders..

One way for closely held corporations (such as small family-run businesses) to avoid the double taxation feature is to elect to be treated as an S corporationA corporation that, after meeting certain eligibility criteria, can elect to be treated like a partnership for tax purposes, thus avoiding paying corporate income tax.. An S corporation (the name comes from the applicable subsection of the tax law) can choose to be taxed like a partnership or sole proprietorship. In other words, it is taxed only once, at the shareholder level when a dividend is declared, and not at the corporate level. Shareholders then pay personal income tax when they receive their share of the corporate profits. An S corporation is formed and treated just like any other corporation; the only difference is in tax treatment. S corporations provide the limited liability feature of corporations but the single-level taxation benefits of sole proprietorships by not paying any corporate taxes. There are some important restrictions on S corporations, however. They cannot have more than one hundred shareholders, all of whom must be U.S. citizens or resident aliens; can have only one class of stock; and cannot be members of an affiliated group of companies. These restrictions ensure that “S” tax treatment is reserved only for small businesses.

A corporation is a separate legal entity. Owners of corporations are known as shareholders and can range from a few in closely held corporations to millions in publicly held corporations. Shareholders of corporations have limited liability, but most are subject to double taxation of corporate profits. Certain small businesses can avoid double taxation by electing to be treated as S corporations under the tax laws. State law charters corporations. Shareholders elect a board of directors, who in turn appoint corporate officers to manage the company.

By now you should understand how easy yet dangerous it is to do business as a sole proprietor, and why many business organizations are drawn to the corporation as a form for doing business. As flexible as the corporation is, however, it is probably best suited for larger businesses. Annual meeting requirements, the need for directors and officers, and the unattractive taxation features make corporations unwieldy and expensive for smaller businesses. A form of business organization that provides the ease and simplicity of sole proprietorships, but the limited liability of corporations, would be much better suited for a wide range of business operations.

A limited liability company (LLC)A hybrid form of business that provides limited liability to owners while being treated as a partnership for tax purposes. is a good solution to this problem. LLCs are a “hybrid” form of business organization that offer the limited liability feature of corporations but the tax benefits of partnerships. Owners of LLCs are called membersOwners of limited liability companies.. Just like a sole proprietorship, it is possible to create an LLC with only one member. LLC members can be real persons or they can be other LLCs, corporations, or partnerships. Compared to limited partnerships, LLC members can participate in day-to-day management of the business. Compared to S corporations, LLC members can be other corporations or partnerships, are not restricted in number, and may be residents of other countries.

Taxation of LLCs is very flexible. Essentially, every tax year the LLC can choose how it wishes to be taxed. It may want to be taxed as a corporation, for example, and pay corporate income tax on net income. Or it may choose instead to have income “flow through” the corporate form to the member-shareholders, who then pay personal income tax just as in a partnership. Sophisticated tax planning becomes possible with LLCs because tax treatment can vary by year.

LLCs are formed by filing the articles of organization with the state agency charged with chartering business entities, typically the Secretary of State. Starting an LLC is often easier than starting a corporation. In fact, you might be startled at how easy it is to start an LLC; typical LLC statutes require only the name of the LLC and the contact information for the LLC’s legal agent (in case someone decides to file a lawsuit against the LLC). In most states, forming an LLC can be done by any competent business professional without any legal assistance, for minimal time and cost. Unlike corporations, there is no requirement for an LLC to issue stock certificates, maintain annual filings, elect a board of directors, hold shareholder meetings, appoint officers, or engage in any regular maintenance of the entity. Most states require LLCs to have the letters “LLC” or words “Limited Liability Company” in the official business name. Of course, LLCs can also file d.b.a. filings to assume another name.

Although the articles of organization are all that is necessary to start an LLC, it is advisable for the LLC members to enter into a written LLC operating agreementAn agreement (usually written) among LLC members governing the LLC’s management, rights, and duties.. The operating agreement typically sets forth how the business will be managed and operated. It may also contain a buy/sell agreement just like a partnership agreement. The operating agreement allows members to run their LLCs any way they wish to, but it can also be a trap for the unwary. LLC law is relatively new compared to corporation law, so the absence of an operating agreement can make it very difficult to resolve disputes among members.

LLCs are not without disadvantages. Since they are a separate legal entity from their members, members must take care to interact with LLCs at arm’s length, because the risk of piercing the veil exists with LLCs as much as it does with corporations. Fundraising for an LLC can be as difficult as it is for a sole proprietorship, especially in the early stages of an LLC’s business operations. Most lenders require LLC members to personally guarantee any loans the LLC may take out. Finally, LLCs are not the right form for taking a company public and selling stock. Fortunately, it is not difficult to convert an LLC into a corporation, so many start-up business begin as LLCs and eventually convert into corporations prior to their initial public offering (IPO).

A related entity to the LLC is the limited liability partnership, or LLP. Be careful not to confuse limited liability partnerships with limited partnerships. LLPs are just like LLCs but are designed for professionals who do business as partners. They allow the partnership to pass through income for tax purposes, but retain limited liability for all partners. LLPs are especially popular with doctors, architects, accountants, and lawyers. Most of the major accounting firms have now converted their corporate forms into LLPs.

The limited liability company (LLC) represents a new trend toward business organization. It allows owners, called members, to have limited liability just like corporations. Unlike corporations, however, LLCs can avoid double taxation by choosing to be taxed like a partnership or sole proprietorship. Unless a business wishes to become publicly traded on a stock exchange, the LLC is probably the most flexible, most affordable, and most compatible form for doing business today. The limited liability partnership (LLP) is similar to the LLC, except it is designed for professionals such as accountants or lawyers who do business as partners.

Most economists and public policy officials believe that the American economy is a key anchor to American society and values. Private enterprise and the profit motive allow innovation and entrepreneurship to flourish, leading to prosperity and peace. Underlying the strength of American business enterprises is a flexible and easy-to-manage legal system that allows business owners many options in choosing how to organize their operations. The sole proprietorship, which provides autonomy and ease in creation, is a dangerous form to do business because of unlimited liability. The general partnership allows business partners to do business together but similarly carries unlimited liability. The corporation provides limited liability for its owners but can be unwieldy and cumbersome to manage, with numerous technical requirements in creation and ongoing management. Limited liability entities, such as the limited liability company and limited liability partnership, provide the most flexible choice for doing business, multiple options for tax planning, and limited liability for owners.