If you think that a blank sheet of paper or a blinking cursor on the computer screen is a scary sight, you are not alone. Many writers, students, and employees find that beginning to write can be intimidating. When faced with a blank page, however, experienced writers remind themselves that writing, like other everyday activities, is a process. Every process, from writing to cooking, bike riding, and learning to use a new cell phone, will get significantly easier with practice.

Just as you need a recipe, ingredients, and proper tools to cook a delicious meal, you also need a plan, resources, and adequate time to create a good written composition. In other words, writing is a process that requires following steps and using strategies to accomplish your goals.

These are the five steps in the writing process:

Effective writing can be simply described as good ideas that are expressed well and arranged in the proper order. This chapter will give you the chance to work on all these important aspects of writing. Although many more prewriting strategies exist, this chapter covers six: using experience and observations, freewriting, asking questions, brainstorming, mapping, and searching the Internet. Using the strategies in this chapter can help you overcome the fear of the blank page and confidently begin the writing process.

Prewriting is the stage of the writing process during which you transfer your abstract thoughts into more concrete ideas in ink on paper (or in type on a computer screen). Although prewriting techniques can be helpful in all stages of the writing process, the following four strategies are best used when initially deciding on a topic:

At this stage in the writing process, it is OK if you choose a general topic. Later you will learn more prewriting strategies that will narrow the focus of the topic.

In addition to understanding that writing is a process, writers also understand that choosing a good general topic for an assignment is an essential step. Sometimes your instructor will give you an idea to begin an assignment, and other times your instructor will ask you to come up with a topic on your own. A good topic not only covers what an assignment will be about but also fits the assignment’s purposeThe reason(s) why a writer creates a document. and its audienceThe individual(s) or group(s) whom the writer intends to address..

In this chapter, you will follow a writer named Mariah as she prepares a piece of writing. You will also be planning one of your own. The first important step is for you to tell yourself why you are writing (to inform, to explain, or some other purpose) and for whom you are writing. Write your purpose and your audience on your own sheet of paper, and keep the paper close by as you read and complete exercises in this chapter.

My purpose: ____________________________________________

My audience: ____________________________________________

When selecting a topic, you may also want to consider something that interests you or something based on your own life and personal experiences. Even everyday observations can lead to interesting topics. After writers think about their experiences and observations, they often take notes on paper to better develop their thoughts. These notes help writers discover what they have to say about their topic.

Have you seen an attention-grabbing story on your local news channel? Many current issues appear on television, in magazines, and on the Internet. These can all provide inspiration for your writing.

Reading plays a vital role in all the stages of the writing process, but it first figures in the development of ideas and topics. Different kinds of documents can help you choose a topic and also develop that topic. For example, a magazine advertising the latest research on the threat of global warming may catch your eye in the supermarket. This cover may interest you, and you may consider global warming as a topic. Or maybe a novel’s courtroom drama sparks your curiosity of a particular lawsuit or legal controversy.

After you choose a topic, critical reading is essential to the development of a topic. While reading almost any document, you evaluate the author’s point of view by thinking about his main idea and his support. When you judge the author’s argument, you discover more about not only the author’s opinion but also your own. If this step already seems daunting, remember that even the best writers need to use prewriting strategies to generate ideas.

The steps in the writing process may seem time consuming at first, but following these steps will save you time in the future. The more you plan in the beginning by reading and using prewriting strategies, the less time you may spend writing and editing later because your ideas will develop more swiftly.

Prewriting strategies depend on your critical reading skills. Reading prewriting exercises (and outlines and drafts later in the writing process) will further develop your topic and ideas. As you continue to follow the writing process, you will see how Mariah uses critical reading skills to assess her own prewriting exercises.

FreewritingA prewriting strategy in which writers write freely about any topic for a set amount of time (usually three to five minutes). is an exercise in which you write freely about any topic for a set amount of time (usually three to five minutes). During the time limit, you may jot down any thoughts that come to your mind. Try not to worry about grammar, spelling, or punctuation. Instead, write as quickly as you can without stopping. If you get stuck, just copy the same word or phrase over and over until you come up with a new thought.

Writing often comes easier when you have a personal connection with the topic you have chosen. Remember, to generate ideas in your freewriting, you may also think about readings that you have enjoyed or that have challenged your thinking. Doing this may lead your thoughts in interesting directions.

Quickly recording your thoughts on paper will help you discover what you have to say about a topic. When writing quickly, try not to doubt or question your ideas. Allow yourself to write freely and unselfconsciously. Once you start writing with few limitations, you may find you have more to say than you first realized. Your flow of thoughts can lead you to discover even more ideas about the topic. Freewriting may even lead you to discover another topic that excites you even more.

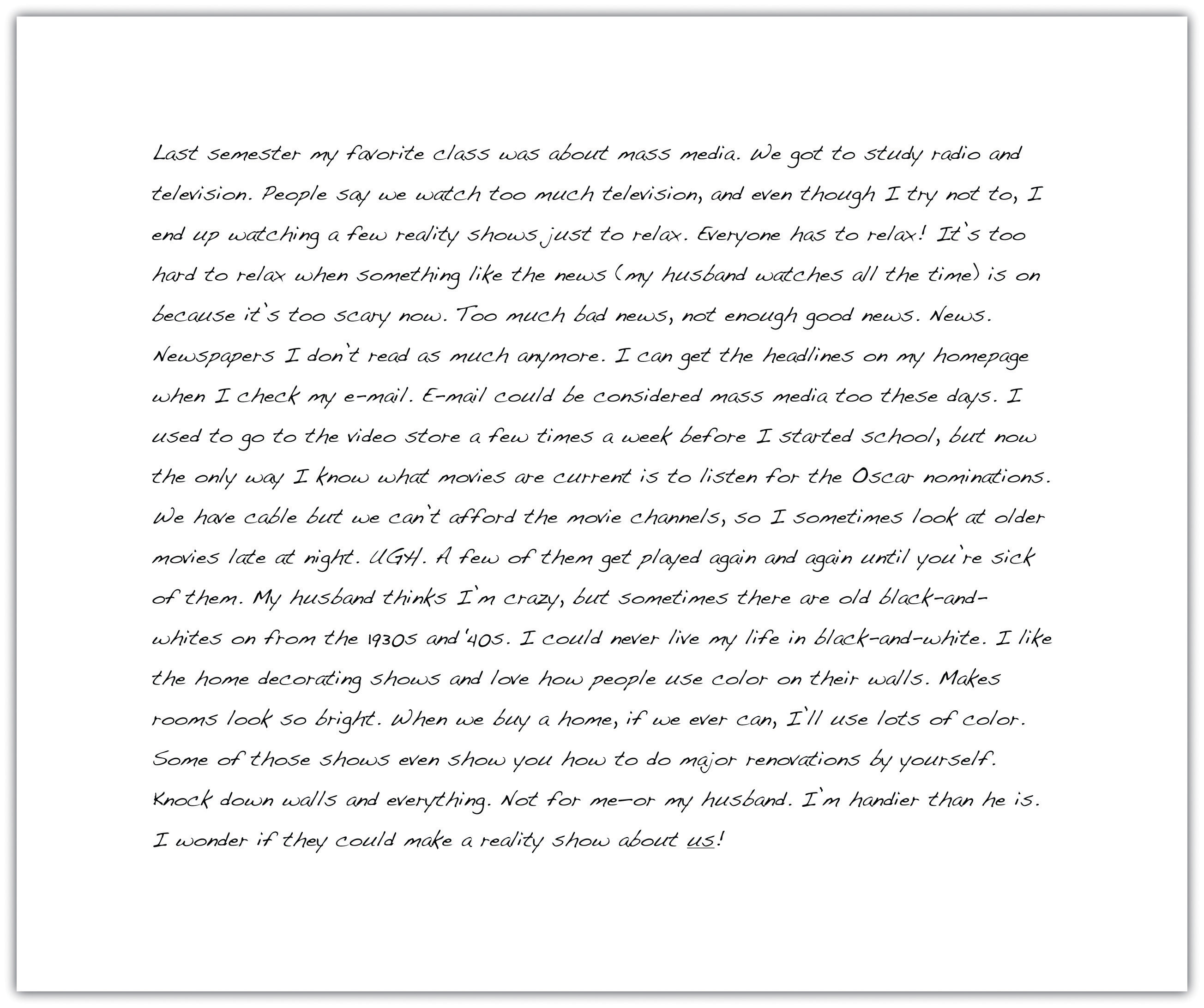

Look at Mariah’s example. The instructor allowed the members of the class to choose their own topics, and Mariah thought about her experiences as a communications major. She used this freewriting exercise to help her generate more concrete ideas from her own experience.

Some prewriting strategies can be used together. For example, you could use experience and observations to come up with a topic related to your course studies. Then you could use freewriting to describe your topic in more detail and figure out what you have to say about it.

Freewrite about one event you have recently experienced. With this event in mind, write without stopping for five minutes. After you finish, read over what you wrote. Does anything stand out to you as a good general topic to write about?

Who? What? Where? When? Why? How? In everyday situations, you pose these kinds of questions to get more information. Who will be my partner for the project? When is the next meeting? Why is my car making that odd noise? Even the title of this chapter begins with the question “How do I begin?”

You seek the answers to these questions to gain knowledge, to better understand your daily experiences, and to plan for the future. Asking these types of questions will also help you with the writing process. As you choose your topic, answering these questions can help you revisit the ideas you already have and generate new ways to think about your topic. You may also discover aspects of the topic that are unfamiliar to you and that you would like to learn more about. All these idea-gathering techniques will help you plan for future work on your assignment.

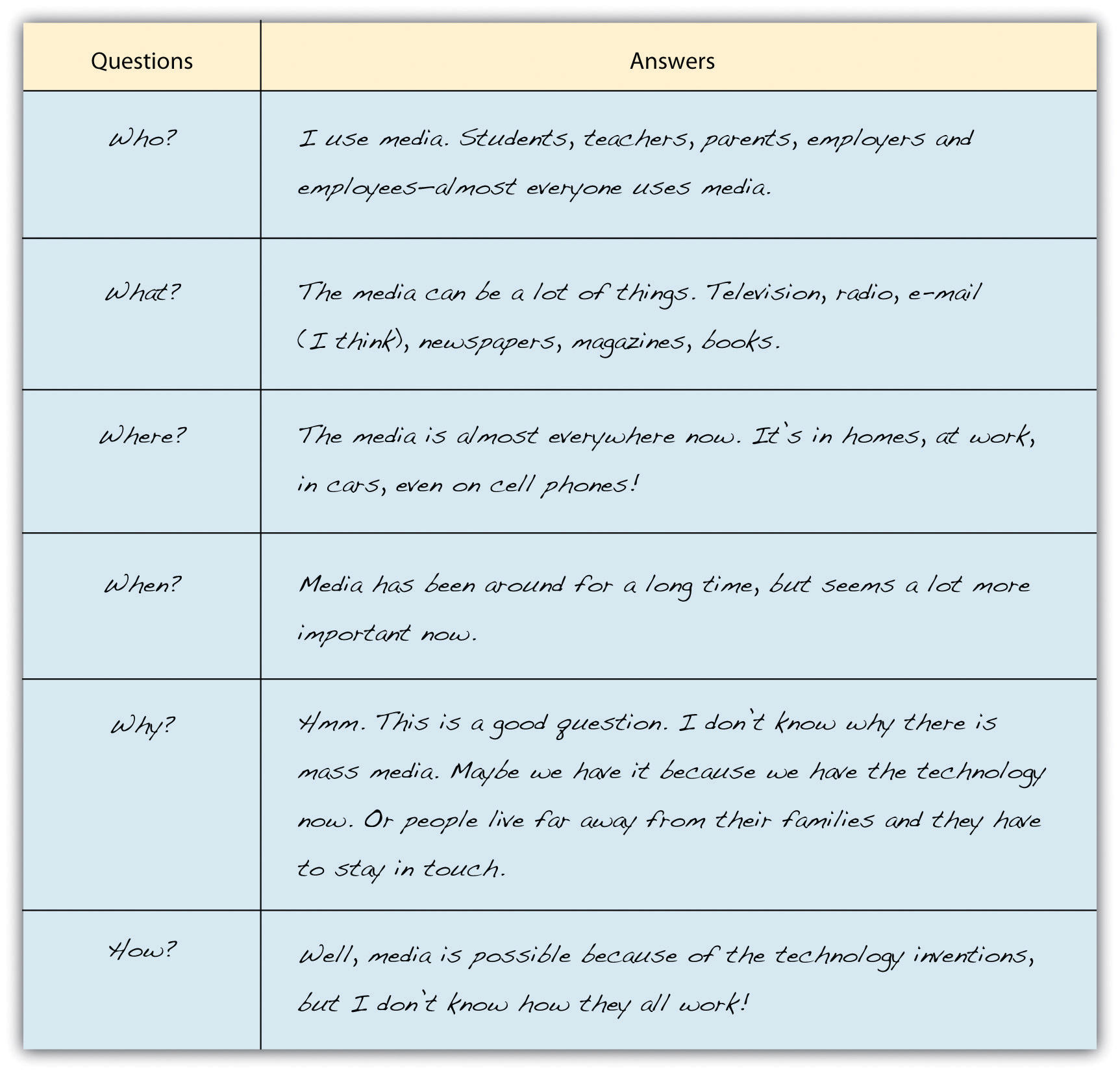

When Mariah reread her freewriting notes, she found she had rambled and her thoughts were disjointed. She realized that the topic that interested her most was the one she started with, the media. She then decided to explore that topic by asking herself questions about it. Her purpose was to refine media into a topic she felt comfortable writing about. To see how asking questions can help you choose a topic, take a look at the following chart that Mariah completed to record her questions and answers. She asked herself the questions that reporters and journalists use to gather information for their stories. The questions are often called the 5WH questionsThe questions that reporters and journalists use to gather information for their stories and that writers use in the writing process: Who? What? Where? When? Why? How?, after their initial letters.

Figure 8.1 Asking Questions

Prewriting is very purpose driven; it does not follow a set of hard-and-fast rules. The purpose of prewriting is to find and explore ideas so that you will be prepared to write. A prewriting technique like asking questions can help you both find a topic and explore it. The key to effective prewriting is to use the techniques that work best for your thinking process. Freewriting may not seem to fit your thinking process, but keep an open mind. It may work better than you think. Perhaps brainstorming a list of topics might better fit your personal style. Mariah found freewriting and asking questions to be fruitful strategies to use. In your own prewriting, use the 5WH questions in any way that benefits your planning.

Choose a general topic idea from the prewriting you completed in Note 8.9 "Exercise 1". Then read each question and use your own paper to answer the 5WH questions. As with Mariah when she explored her writing topic for more detail, it is OK if you do not know all the answers. If you do not know an answer, use your own opinion to speculate, or guess. You may also use factual information from books or articles you previously read on your topic. Later in the chapter, you will read about additional ways (like searching the Internet) to answer your questions and explore your guesses.

5WH Questions

Who?

_____________________________________________________

What?

_____________________________________________________

Where?

_____________________________________________________

When?

_____________________________________________________

Why?

_____________________________________________________

How?

_____________________________________________________

Now that you have completed some of the prewriting exercises, you may feel less anxious about starting a paper from scratch. With some ideas down on paper (or saved on a computer), writers are often more comfortable continuing the writing process. After identifying a good general topic, you, too, are ready to continue the process.

Write your general topic on your own sheet of paper, under where you recorded your purpose and audience. Choose it from among the topics you listed or explored during the prewriting you have done so far. Make sure it is one you feel comfortable with and feel capable of writing about.

My general topic: ____________________________________________

You may find that you need to adjust your topic as you move through the writing stages (and as you complete the exercises in this chapter). If the topic you have chosen is not working, you can repeat the prewriting activities until you find a better one.

The prewriting techniques of freewriting and asking questions helped Mariah think more about her topic, but the following prewriting strategies can help her (and you) narrow the focus of the topic:

Narrowing the focus means breaking up the topic into subtopics, or more specific points. Generating lots of subtopics will help you eventually select the ones that fit the assignment and appeal to you and your audience.

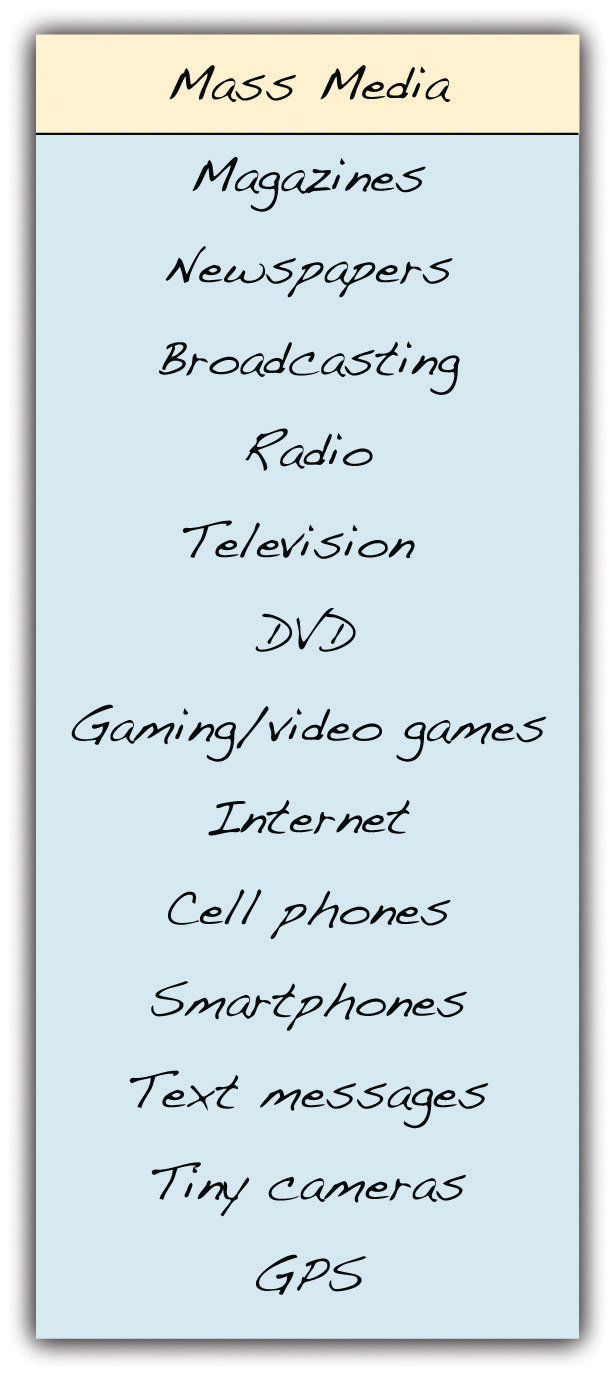

After rereading her syllabus, Mariah realized her general topic, mass media, is too broad for her class’s short paper requirement. Three pages are not enough to cover all the concerns in mass media today. Mariah also realized that although her readers are other communications majors who are interested in the topic, they may want to read a paper about a particular issue in mass media.

BrainstormingA prewriting strategy similar to list making. Writers start with a general category and list specific items that fall into the category. is similar to list making. You can make a list on your own or in a group with your classmates. Start with a blank sheet of paper (or a blank computer document) and write your general topic across the top. Underneath your topic, make a list of more specific ideas. Think of your general topic as a broad category and the list items as things that fit in that category. Often you will find that one item can lead to the next, creating a flow of ideas that can help you narrow your focus to a more specific paper topic.

The following is Mariah’s brainstorming list:

From this list, Mariah could narrow her focus to a particular technology under the broad category of mass media.

Imagine you have to write an e-mail to your current boss explaining your prior work experience, but you do not know where to start. Before you begin the e-mail, you can use the brainstorming technique to generate a list of employers, duties, and responsibilities that fall under the general topic “work experience.”

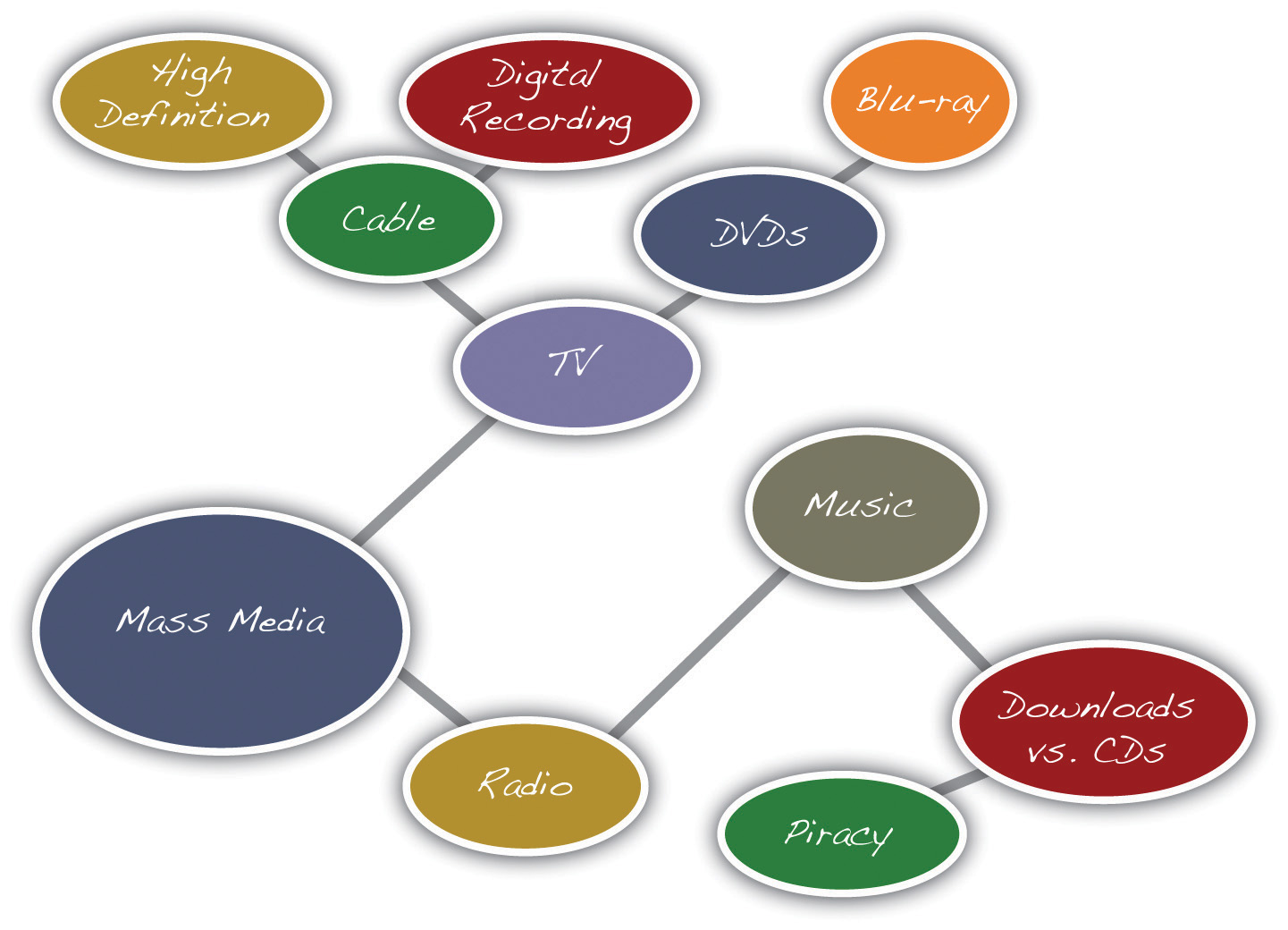

Idea mappingA prewriting strategy in which writers cluster ideas on paper using circles, lines, and arrows. allows you to visualize your ideas on paper using circles, lines, and arrows. This technique is also known as clustering because ideas are broken down and clustered, or grouped together. Many writers like this method because the shapes show how the ideas relate or connect, and writers can find a focused topic from the connections mapped. Using idea mapping, you might discover interesting connections between topics that you had not thought of before.

To create an idea map, start with your general topic in a circle in the center of a blank sheet of paper. Then write specific ideas around it and use lines or arrows to connect them together. Add and cluster as many ideas as you can think of.

In addition to brainstorming, Mariah tried idea mapping. Review the following idea map that Mariah created:

Figure 8.2 Idea Map

Notice Mariah’s largest circle contains her general topic, mass media. Then, the general topic branches into two subtopics written in two smaller circles: television and radio. The subtopic television branches into even more specific topics: cable and DVDs. From there, Mariah drew more circles and wrote more specific ideas: high definition and digital recording from cable and Blu-ray from DVDs. The radio topic led Mariah to draw connections between music, downloads versus CDs, and, finally, piracy.

From this idea map, Mariah saw she could consider narrowing the focus of her mass media topic to the more specific topic of music piracy.

Using search engines on the Internet is a good way to see what kinds of websites are available on your topic. Writers use search engines not only to understand more about the topic’s specific issues but also to get better acquainted with their audience.

Look back at the chart you completed in Note 8.12 "Exercise 2". Did you guess at any of the answers? Searching the Internet may help you find answers to your questions and confirm your guesses. Be choosy about the websites you use. Make sure they are reliable sources for the kind of information you seek.

When you search the Internet, type some key words from your broad topic or words from your narrowed focus into your browser’s search engine (many good general and specialized search engines are available for you to try). Then look over the results for relevant and interesting articles.

Results from an Internet search show writers the following information:

If the search engine results are not what you are looking for, revise your key words and search again. Some search engines also offer suggestions for related searches that may give you better results.

Mariah typed the words music piracy from her idea map into the search engine Google.

Figure 8.3 Useful Search Engine Results

Not all the results online search engines return will be useful or reliable. Give careful consideration to the reliability of an online source before selecting a topic based on it. Remember that factual information can be verified in other sources, both online and in print. If you have doubts about any information you find, either do not use it or identify it as potentially unreliable.

The results from Mariah’s search included websites from university publications, personal blogs, online news sources, and lots of legal cases sponsored by the recording industry. Reading legal jargon made Mariah uncomfortable with the results, so she decided to look further. Reviewing her map, she realized that she was more interested in consumer aspects of mass media, so she refocused her search to media technology and the sometimes confusing array of expensive products that fill electronics stores. Now, Mariah considers a paper topic on the products that have fed the mass media boom in everyday lives.

In Note 8.12 "Exercise 2", you chose a possible topic and explored it by answering questions about it using the 5WH questions. However, this topic may still be too broad. Here, in Note 8.21 "Exercise 3", choose and complete one of the prewriting strategies to narrow the focus. Use either brainstorming, idea mapping, or searching the Internet.

Collaboration

Please share with a classmate and compare your answers. Share what you found and what interests you about the possible topic(s).

Prewriting strategies are a vital first step in the writing process. First, they help you first choose a broad topic and then they help you narrow the focus of the topic to a more specific idea. An effective topic ensures that you are ready for the next step.

Developing a Good Topic

The following checklist can help you decide if your narrowed topic is a good topic for your assignment.

With your narrowed focus in mind, answer the bulleted questions in the checklist for developing a good topic. If you can answer “yes” to all the questions, write your topic on the line. If you answer “no” to any of the questions, think about another topic or adjust the one you have and try the prewriting strategies again.

My narrowed topic: ____________________________________________

Your prewriting activities and readings have helped you gather information for your assignment. The more you sort through the pieces of information you found, the more you will begin to see the connections between them. Patterns and gaps may begin to stand out. But only when you start to organize your ideas will you be able to translate your raw insights into a form that will communicate meaning to your audience.

Longer papers require more reading and planning than shorter papers do. Most writers discover that the more they know about a topic, the more they can write about it with intelligence and interest.

When you write, you need to organize your ideas in an order that makes sense. The writing you complete in all your courses exposes how analytically and critically your mind works. In some courses, the only direct contact you may have with your instructor is through the assignments you write for the course. You can make a good impression by spending time ordering your ideas.

Order refers to your choice of what to present first, second, third, and so on in your writing. The order you pick closely relates to your purpose for writing that particular assignment. For example, when telling a story, it may be important to first describe the background for the action. Or you may need to first describe a 3-D movie projector or a television studio to help readers visualize the setting and scene. You may want to group your support effectively to convince readers that your point of view on an issue is well reasoned and worthy of belief.

In longer pieces of writing, you may organize different parts in different ways so that your purpose stands out clearly and all parts of the paper work together to consistently develop your main point.

The three common methods of organizing writing are chronological orderA method of organization that arranges ideas according to time., spatial orderA method of organization that arranges ideas according to physical characteristics or appearance., and order of importanceA method of organization that arranges ideas according to their significance.. You will learn more about these in Chapter 9 "Writing Essays: From Start to Finish"; however, you need to keep these methods of organization in mind as you plan how to arrange the information you have gathered in an outline. An outline is a written plan that serves as a skeleton for the paragraphs you write. Later, when you draft paragraphs in the next stage of the writing process, you will add support to create “flesh” and “muscle” for your assignment.

When you write, your goal is not only to complete an assignment but also to write for a specific purpose—perhaps to inform, to explain, to persuade, or for a combination of these purposes. Your purpose for writing should always be in the back of your mind, because it will help you decide which pieces of information belong together and how you will order them. In other words, choose the order that will most effectively fit your purpose and support your main point.

Table 8.1 "Order versus Purpose" shows the connection between order and purpose.

Table 8.1 Order versus Purpose

| Order | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Chronological Order | To explain the history of an event or a topic |

| To tell a story or relate an experience | |

| To explain how to do or make something | |

| To explain the steps in a process | |

| Spatial Order | To help readers visualize something as you want them to see it |

| To create a main impression using the senses (sight, touch, taste, smell, and sound) | |

| Order of Importance | To persuade or convince |

| To rank items by their importance, benefit, or significance |

One legitimate question readers always ask about a piece of writing is “What is the big idea?” (You may even ask this question when you are the reader, critically reading an assignment or another document.) Every nonfiction writing task—from the short essay to the ten-page term paper to the lengthy senior thesis—needs a big idea, or a controlling idea, as the spine for the work. The controlling idea is the main idea that you want to present and develop.

For a longer piece of writing, the main idea should be broader than the main idea for a shorter piece of writing. Be sure to frame a main idea that is appropriate for the length of the assignment. Ask yourself, “How many pages will it take for me to explain and explore this main idea in detail?” Be reasonable with your estimate. Then expand or trim it to fit the required length.

The big idea, or controlling idea, you want to present in an essay is expressed in a thesis statementA sentence that presents the controlling idea of an essay. A thesis statement is often one sentence long and states the writer’s point of view.. A thesis statement is often one sentence long, and it states your point of view. The thesis statement is not the topic of the piece of writing but rather what you have to say about that topic and what is important to tell readers.

Table 8.2 "Topics and Thesis Statements" compares topics and thesis statements.

Table 8.2 Topics and Thesis Statements

| Topic | Thesis Statement |

|---|---|

| Music piracy | The recording industry fears that so-called music piracy will diminish profits and destroy markets, but it cannot be more wrong. |

| The number of consumer choices available in media gear | Everyone wants the newest and the best digital technology, but the choices are extensive, and the specifications are often confusing. |

| E-books and online newspapers increasing their share of the market | E-books and online newspapers will bring an end to print media as we know it. |

| Online education and the new media | Someday, students and teachers will send avatars to their online classrooms. |

The first thesis statement you write will be a preliminary thesis statement, or a working thesis statementThe first thesis statement writers use while outlining an assignment. A working thesis statement may change during the writing process.. You will need it when you begin to outline your assignment as a way to organize it. As you continue to develop the arrangement, you can limit your working thesis statement if it is too broad or expand it if it proves too narrow for what you want to say.

Using the topic you selected in Section 8.1 "Apply Prewriting Models", develop a working thesis statement that states your controlling idea for the piece of writing you are doing. On a sheet of paper, write your working thesis statement.

You will make several attempts before you devise a working thesis statement that you think is effective. Each draft of the thesis statement will bring you closer to the wording that expresses your meaning exactly.

For an essay question on a test or a brief oral presentation in class, all you may need to prepare is a short, informal outline in which you jot down key ideas in the order you will present them. This kind of outline reminds you to stay focused in a stressful situation and to include all the good ideas that help you explain or prove your point.

For a longer assignment, like an essay or a research paper, many college instructors require students to submit a formal outlineA detailed guide that shows how all the supporting ideas in an essay are related to one other. before writing a major paper as a way to be sure you are on the right track and are working in an organized manner. A formal outline is a detailed guide that shows how all your supporting ideas relate to each other. It helps you distinguish between ideas that are of equal importance and ones that are of lesser importance. You build your paper based on the framework created by the outline.

Instructors may also require you to submit an outline with your final draft to check the direction of the assignment and the logic of your final draft. If you are required to submit an outline with the final draft of a paper, remember to revise the outline to reflect any changes you made while writing the paper.

There are two types of formal outlines: the topic outline and the sentence outline. You format both types of formal outlines in the same way.

Here is what the skeleton of a traditional formal outline looks like. The indention helps clarify how the ideas are related.

Introduction

Thesis statement

Main point 1 → becomes the topic sentence of body paragraph 1

Supporting detail → becomes a support sentence of body paragraph 1

Supporting detail

Supporting detail

Main point 2 → becomes the topic sentence of body paragraph 2

Main point 3 → becomes the topic sentence of body paragraph 3

In an outline, any supporting detail can be developed with subpoints. For simplicity, the model shows them only under the first main point.

Formal outlines are often quite rigid in their organization. As many instructors will specify, you cannot subdivide one point if it is only one part. For example, for every roman numeral I, there must be a For every A, there must be a B. For every arabic numeral 1, there must be a 2. See for yourself on the sample outlines that follow.

A topic outline is the same as a sentence outline except you use words or phrases instead of complete sentences. Words and phrases keep the outline short and easier to comprehend. All the headings, however, must be written in parallel structure. (For more information on parallel structure, see Chapter 7 "Refining Your Writing: How Do I Improve My Writing Technique?".)

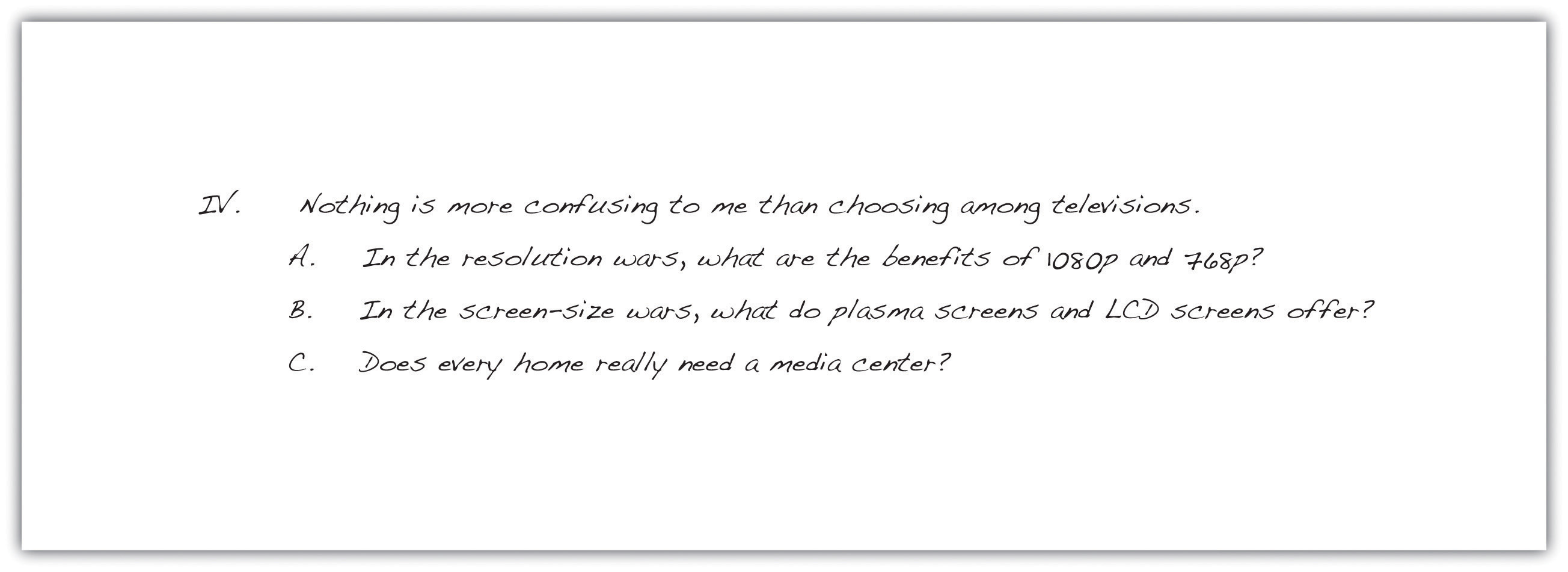

Here is the topic outline that Mariah constructed for the essay she is developing. Her purpose is to inform, and her audience is a general audience of her fellow college students. Notice how Mariah begins with her thesis statement. She then arranges her main points and supporting details in outline form using short phrases in parallel grammatical structure.

Writing an Effective Topic Outline

This checklist can help you write an effective topic outline for your assignment. It will also help you discover where you may need to do additional reading or prewriting.

Word processing programs generally have an automatic numbering feature that can be used to prepare outlines. This feature automatically sets indents and lets you use the tab key to arrange information just as you would in an outline. Although in business this style might be acceptable, in college your instructor might have different requirements. Teach yourself how to customize the levels of outline numbering in your word-processing program to fit your instructor’s preferences.

Using the working thesis statement you wrote in Note 8.32 "Exercise 1" and the reading you did in Section 8.1 "Apply Prewriting Models", construct a topic outline for your essay. Be sure to observe correct outline form, including correct indentions and the use of Roman and arabic numerals and capital letters.

Collaboration

Please share with a classmate and compare your outline. Point out areas of interest from their outline and what you would like to learn more about.

A sentence outline is the same as a topic outline except you use complete sentences instead of words or phrases. Complete sentences create clarity and can advance you one step closer to a draft in the writing process.

Here is the sentence outline that Mariah constructed for the essay she is developing.

The information compiled under each roman numeral will become a paragraph in your final paper. In the previous example, the outline follows the standard five-paragraph essay arrangement, but longer essays will require more paragraphs and thus more roman numerals. If you think that a paragraph might become too long or stringy, add an additional paragraph to your outline, renumbering the main points appropriately.

PowerPoint presentations, used both in schools and in the workplace, are organized in a way very similar to formal outlines. PowerPoint presentations often contain information in the form of talking points that the presenter develops with more details and examples than are contained on the PowerPoint slide.

Expand the topic outline you prepared in Note 8.41 "Exercise 2" to make it a sentence outline. In this outline, be sure to include multiple supporting points for your main topic even if your topic outline does not contain them. Be sure to observe correct outline form, including correct indentions and the use of Roman and arabic numerals and capital letters.

DraftingThe stage of the writing process in which the writer develops a complete first version of a piece of writing. is the stage of the writing process in which you develop a complete first version of a piece of writing.

Even professional writers admit that an empty page scares them because they feel they need to come up with something fresh and original every time they open a blank document on their computers. Because you have completed the first two steps in the writing process, you have already recovered from empty page syndrome. You have hours of prewriting and planning already done. You know what will go on that blank page: what you wrote in your outline.

Your objective for this portion of Chapter 8 "The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?" is to draft the body paragraphs of a standard five-paragraph essay. A five-paragraph essay contains an introduction, three body paragraphs, and a conclusion. If you are more comfortable starting on paper than on the computer, you can start on paper and then type it before you revise. You can also use a voice recorder to get yourself started, dictating a paragraph or two to get you thinking. In this lesson, Mariah does all her work on the computer, but you may use pen and paper or the computer to write a rough draft.

What makes the writing process so beneficial to writers is that it encourages alternatives to standard practices while motivating you to develop your best ideas. For instance, the following approaches, done alone or in combination with others, may improve your writing and help you move forward in the writing process:

Of all of these considerations, keeping your purpose and your audience at the front of your mind is the most important key to writing success. If your purpose is to persuade, for example, you will present your facts and details in the most logical and convincing way you can.

Your purpose will guide your mind as you compose your sentences. Your audience will guide word choice. Are you writing for experts, for a general audience, for other college students, or for people who know very little about your topic? Keep asking yourself what your readers, with their background and experience, need to be told in order to understand your ideas. How can you best express your ideas so they are totally clear and your communication is effective?

You may want to identify your purpose and audience on an index card that you clip to your paper (or keep next to your computer). On that card, you may want to write notes to yourself—perhaps about what that audience might not know or what it needs to know—so that you will be sure to address those issues when you write. It may be a good idea to also state exactly what you want to explain to that audience, or to inform them of, or to persuade them about.

Many of the documents you produce at work target a particular audience for a particular purpose. You may find that it is highly advantageous to know as much as you can about your target audience and to prepare your message to reach that audience, even if the audience is a coworker or your boss. Menu language is a common example. Descriptions like “organic romaine” and “free-range chicken” are intended to appeal to a certain type of customer though perhaps not to the same customer who craves a thick steak. Similarly, mail-order companies research the demographics of the people who buy their merchandise. Successful vendors customize product descriptions in catalogs to appeal to their buyers’ tastes. For example, the product descriptions in a skateboarder catalog will differ from the descriptions in a clothing catalog for mature adults.

Using the topic for the essay that you outlined in Section 8.2 "Outlining", describe your purpose and your audience as specifically as you can. Use your own sheet of paper to record your responses. Then keep these responses near you during future stages of the writing process.

My purpose: ____________________________________________

____________________________________________

____________________________________________

My audience: ____________________________________________

____________________________________________

____________________________________________

A draft is a complete version of a piece of writing, but it is not the final version. The step in the writing process after drafting, as you may remember, is revising. During revising, you will have the opportunity to make changes to your first draft before you put the finishing touches on it during the editing and proofreading stage. A first draft gives you a working version that you can later improve.

Workplace writing in certain environments is done by teams of writers who collaborate on the planning, writing, and revising of documents, such as long reports, technical manuals, and the results of scientific research. Collaborators do not need to be in the same room, the same building, or even the same city. Many collaborations are conducted over the Internet.

In a perfect collaboration, each contributor has the right to add, edit, and delete text. Strong communication skills, in addition to strong writing skills, are important in this kind of writing situation because disagreements over style, content, process, emphasis, and other issues may arise.

The collaborative software, or document management systems, that groups use to work on common projects is sometimes called groupware or workgroup support systems.

The reviewing tool on some word-processing programs also gives you access to a collaborative tool that many smaller workgroups use when they exchange documents. You can also use it to leave comments to yourself.

If you invest some time now to investigate how the reviewing tool in your word processor works, you will be able to use it with confidence during the revision stage of the writing process. Then, when you start to revise, set your reviewing tool to track any changes you make, so you will be able to tinker with text and commit only those final changes you want to keep.

If you have been using the information in this chapter step by step to help you develop an assignment, you already have both a formal topic outline and a formal sentence outline to direct your writing. Knowing what a first draft looks like will help you make the creative leap from the outline to the first draft. A first draft should include the following elements:

These elements follow the standard five-paragraph essay format, which you probably first encountered in high school. This basic format is valid for most essays you will write in college, even much longer ones. For now, however, Mariah focuses on writing the three body paragraphs from her outline. Chapter 9 "Writing Essays: From Start to Finish" covers writing introductions and conclusions, and you will read Mariah’s introduction and conclusion in Chapter 9 "Writing Essays: From Start to Finish".

Topic sentences make the structure of a text and the writer’s basic arguments easy to locate and comprehend. In college writing, using a topic sentence in each paragraph of the essay is the standard rule. However, the topic sentence does not always have to be the first sentence in your paragraph even if it the first item in your formal outline.

When you begin to draft your paragraphs, you should follow your outline fairly closely. After all, you spent valuable time developing those ideas. However, as you begin to express your ideas in complete sentences, it might strike you that the topic sentence might work better at the end of the paragraph or in the middle. Try it. Writing a draft, by its nature, is a good time for experimentation.

The topic sentence can be the first, middle, or final sentence in a paragraph. The assignment’s audience and purpose will often determine where a topic sentence belongs. When the purpose of the assignment is to persuade, for example, the topic sentence should be the first sentence in a paragraph. In a persuasive essay, the writer’s point of view should be clearly expressed at the beginning of each paragraph.

Choosing where to position the topic sentence depends not only on your audience and purpose but also on the essay’s arrangement, or order. When you organize information according to order of importance, the topic sentence may be the final sentence in a paragraph. All the supporting sentences build up to the topic sentence. Chronological order may also position the topic sentence as the final sentence because the controlling idea of the paragraph may make the most sense at the end of a sequence.

When you organize information according to spatial order, a topic sentence may appear as the middle sentence in a paragraph. An essay arranged by spatial order often contains paragraphs that begin with descriptions. A reader may first need a visual in his or her mind before understanding the development of the paragraph. When the topic sentence is in the middle, it unites the details that come before it with the ones that come after it.

As you read critically throughout the writing process, keep topic sentences in mind. You may discover topic sentences that are not always located at the beginning of a paragraph. For example, fiction writers customarily use topic ideas, either expressed or implied, to move readers through their texts. In nonfiction writing, such as popular magazines, topic sentences are often used when the author thinks it is appropriate (based on the audience and the purpose, of course). A single topic sentence might even control the development of a number of paragraphs. For more information on topic sentences, please see Chapter 6 "Writing Paragraphs: Separating Ideas and Shaping Content".

Developing topic sentences and thinking about their placement in a paragraph will prepare you to write the rest of the paragraph.

The paragraph is the main structural component of an essay as well as other forms of writing. Each paragraph of an essay adds another related main idea to support the writer’s thesis, or controlling idea. Each related main idea is supported and developed with facts, examples, and other details that explain it. By exploring and refining one main idea at a time, writers build a strong case for their thesis.

Paragraph Length

How long should a paragraph be?

One answer to this important question may be “long enough”—long enough for you to address your points and explain your main idea. To grab attention or to present succinct supporting ideas, a paragraph can be fairly short and consist of two to three sentences. A paragraph in a complex essay about some abstract point in philosophy or archaeology can be three-quarters of a page or more in length. As long as the writer maintains close focus on the topic and does not ramble, a long paragraph is acceptable in college-level writing. In general, try to keep the paragraphs longer than one sentence but shorter than one full page of double-spaced text.

Journalistic style often calls for brief two- or three-sentence paragraphs because of how people read the news, both online and in print. Blogs and other online information sources often adopt this paragraphing style, too. Readers often skim the first paragraphs of a great many articles before settling on the handful of stories they want to read in detail.

You may find that a particular paragraph you write may be longer than one that will hold your audience’s interest. In such cases, you should divide the paragraph into two or more shorter paragraphs, adding a topic statement or some kind of transitional word or phrase at the start of the new paragraph. Transition words or phrases show the connection between the two ideas.

In all cases, however, be guided by what you instructor wants and expects to find in your draft. Many instructors will expect you to develop a mature college-level style as you progress through the semester’s assignments.

To build your sense of appropriate paragraph length, use the Internet to find examples of the following items. Copy them into a file, identify your sources, and present them to your instructor with your annotations, or notes.

Now we are finally ready to look over Mariah’s shoulder as she begins to write her essay about digital technology and the confusing choices that consumers face. As she does, you should have in front of you your outline, with its thesis statement and topic sentences, and the notes you wrote earlier in this lesson on your purpose and audience. Reviewing these will put both you and Mariah in the proper mind-set to start.

The following is Mariah’s thesis statement.

Here are the notes that Mariah wrote to herself to characterize her purpose and audience.

Mariah chose to begin by writing a quick introduction based on her thesis statement. She knew that she would want to improve her introduction significantly when she revised. Right now, she just wanted to give herself a starting point. You will read her introduction again in Section 8.4 "Revising and Editing" when she revises it.

Remember Mariah’s other options. She could have started directly with any of the body paragraphs.

You will learn more about writing attention-getting introductions and effective conclusions in Chapter 9 "Writing Essays: From Start to Finish".

With her thesis statement and her purpose and audience notes in front of her, Mariah then looked at her sentence outline. She chose to use that outline because it includes the topic sentences. The following is the portion of her outline for the first body paragraph. The roman numeral II identifies the topic sentence for the paragraph, capital letters indicate supporting details, and arabic numerals label subpoints.

Mariah then began to expand the ideas in her outline into a paragraph. Notice how the outline helped her guarantee that all her sentences in the body of the paragraph develop the topic sentence.

If you write your first draft on the computer, consider creating a new file folder for each course with a set of subfolders inside the course folders for each assignment you are given. Label the folders clearly with the course names, and label each assignment folder and word processing document with a title that you will easily recognize. The assignment name is a good choice for the document. Then use that subfolder to store all the drafts you create. When you start each new draft, do not just write over the last one. Instead, save the draft with a new tag after the title—draft 1, draft 2, and so on—so that you will have a complete history of drafts in case your instructor wishes you to submit them.

In your documents, observe any formatting requirements—for margins, headers, placement of page numbers, and other layout matters—that your instructor requires.

Study how Mariah made the transition from her sentence outline to her first draft. First, copy her outline onto your own sheet of paper. Leave a few spaces between each part of the outline. Then copy sentences from Mariah’s paragraph to align each sentence with its corresponding entry in her outline.

Mariah continued writing her essay, moving to the second and third body paragraphs. She had supporting details but no numbered subpoints in her outline, so she had to consult her prewriting notes for specific information to include.

If you decide to take a break between finishing your first body paragraph and starting the next one, do not start writing immediately when you return to your work. Put yourself back in context and in the mood by rereading what you have already written. This is what Mariah did. If she had stopped writing in the middle of writing the paragraph, she could have jotted down some quick notes to herself about what she would write next.

Preceding each body paragraph that Mariah wrote is the appropriate section of her sentence outline. Notice how she expanded roman numeral III from her outline into a first draft of the second body paragraph. As you read, ask yourself how closely she stayed on purpose and how well she paid attention to the needs of her audience.

Mariah then began her third and final body paragraph using roman numeral IV from her outline.

Reread body paragraphs two and three of the essay that Mariah is writing. Then answer the questions on your own sheet of paper.

A writer’s best choice for a title is one that alludes to the main point of the entire essay. Like the headline in a newspaper or the big, bold title in a magazine, an essay’s title gives the audience a first peek at the content. If readers like the title, they are likely to keep reading.

Following her outline carefully, Mariah crafted each paragraph of her essay. Moving step by step in the writing process, Mariah finished the draft and even included a brief concluding paragraph (you will read her conclusion in Chapter 9 "Writing Essays: From Start to Finish"). She then decided, as the final touch for her writing session, to add an engaging title.

Now you may begin your own first draft, if you have not already done so. Follow the suggestions and the guidelines presented in this section.

Revising and editing are the two tasks you undertake to significantly improve your essay. Both are very important elements of the writing process. You may think that a completed first draft means little improvement is needed. However, even experienced writers need to improve their drafts and rely on peers during revising and editing. You may know that athletes miss catches, fumble balls, or overshoot goals. Dancers forget steps, turn too slowly, or miss beats. For both athletes and dancers, the more they practice, the stronger their performance will become. Web designers seek better images, a more clever design, or a more appealing background for their web pages. Writing has the same capacity to profit from improvement and revision.

Revising and editing allow you to examine two important aspects of your writing separately, so that you can give each task your undivided attention.

How do you get the best out of your revisions and editing? Here are some strategies that writers have developed to look at their first drafts from a fresh perspective. Try them over the course of this semester; then keep using the ones that bring results.

Many people hear the words critic, critical, and criticism and pick up only negative vibes that provoke feelings that make them blush, grumble, or shout. However, as a writer and a thinker, you need to learn to be critical of yourself in a positive way and have high expectations for your work. You also need to train your eye and trust your ability to fix what needs fixing. For this, you need to teach yourself where to look.

Following your outline closely offers you a reasonable guarantee that your writing will stay on purpose and not drift away from the controlling idea. However, when writers are rushed, are tired, or cannot find the right words, their writing may become less than they want it to be. Their writing may no longer be clear and concise, and they may be adding information that is not needed to develop the main idea.

When a piece of writing has unityA quality in which all the ideas in a paragraph and in the entire essay clearly belong and are arranged in an order that makes logical sense., all the ideas in each paragraph and in the entire essay clearly belong and are arranged in an order that makes logical sense. When the writing has coherenceA quality in which the wording of an work clearly indicates how one idea leads to another within a paragraph and from paragraph to paragraph., the ideas flow smoothly. The wording clearly indicates how one idea leads to another within a paragraph and from paragraph to paragraph.

Reading your writing aloud will often help you find problems with unity and coherence. Listen for the clarity and flow of your ideas. Identify places where you find yourself confused, and write a note to yourself about possible fixes.

Sometimes writers get caught up in the moment and cannot resist a good digression. Even though you might enjoy such detours when you chat with friends, unplanned digressions usually harm a piece of writing.

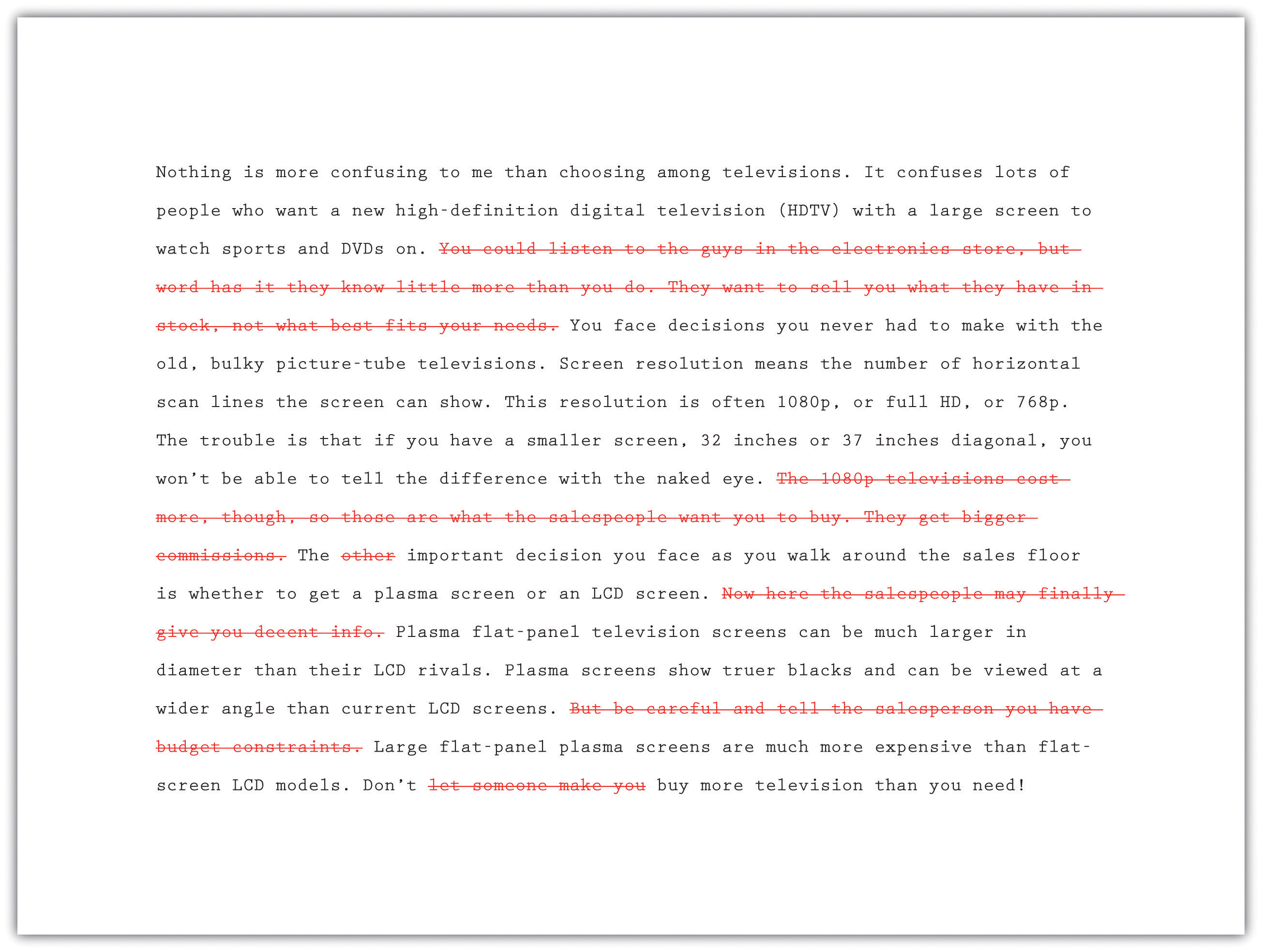

Mariah stayed close to her outline when she drafted the three body paragraphs of her essay she tentatively titled “Digital Technology: The Newest and the Best at What Price?” But a recent shopping trip for an HDTV upset her enough that she digressed from the main topic of her third paragraph and included comments about the sales staff at the electronics store she visited. When she revised her essay, she deleted the off-topic sentences that affected the unity of the paragraph.

Read the following paragraph twice, the first time without Mariah’s changes, and the second time with them.

Answer the following two questions about Mariah’s paragraph:

Collaboration

Please share with a classmate and compare your answers.

When you reread your writing to find revisions to make, look for each type of problem in a separate sweep. Read it straight through once to locate any problems with unity. Read it straight through a second time to find problems with coherence. You may follow this same practice during many stages of the writing process.

Many companies hire copyeditors and proofreaders to help them produce the cleanest possible final drafts of large writing projects. Copyeditors are responsible for suggesting revisions and style changes; proofreaders check documents for any errors in capitalization, spelling, and punctuation that have crept in. Many times, these tasks are done on a freelance basis, with one freelancer working for a variety of clients.

Careful writers use transitionsWords and phrases that show how the ideas in sentences and paragraphs are related. to clarify how the ideas in their sentences and paragraphs are related. These words and phrases help the writing flow smoothly. Adding transitions is not the only way to improve coherence, but they are often useful and give a mature feel to your essays. Table 8.3 "Common Transitional Words and Phrases" groups many common transitions according to their purpose.

Table 8.3 Common Transitional Words and Phrases

| Transitions That Show Sequence or Time | ||

| after | before | later |

| afterward | before long | meanwhile |

| as soon as | finally | next |

| at first | first, second, third | soon |

| at last | in the first place | then |

| Transitions That Show Position | ||

| above | across | at the bottom |

| at the top | behind | below |

| beside | beyond | inside |

| near | next to | opposite |

| to the left, to the right, to the side | under | where |

| Transitions That Show a Conclusion | ||

| indeed | hence | in conclusion |

| in the final analysis | therefore | thus |

| Transitions That Continue a Line of Thought | ||

| consequently | furthermore | additionally |

| because | besides the fact | following this idea further |

| in addition | in the same way | moreover |

| looking further | considering…, it is clear that | |

| Transitions That Change a Line of Thought | ||

| but | yet | however |

| nevertheless | on the contrary | on the other hand |

| Transitions That Show Importance | ||

| above all | best | especially |

| in fact | more important | most important |

| most | worst | |

| Transitions That Introduce the Final Thoughts in a Paragraph or Essay | ||

| finally | last | in conclusion |

| most of all | least of all | last of all |

| All-Purpose Transitions to Open Paragraphs or to Connect Ideas Inside Paragraphs | ||

| admittedly | at this point | certainly |

| granted | it is true | generally speaking |

| in general | in this situation | no doubt |

| no one denies | obviously | of course |

| to be sure | undoubtedly | unquestionably |

| Transitions that Introduce Examples | ||

| for instance | for example | |

| Transitions That Clarify the Order of Events or Steps | ||

| first, second, third | generally, furthermore, finally | in the first place, also, last |

| in the first place, furthermore, finally | in the first place, likewise, lastly | |

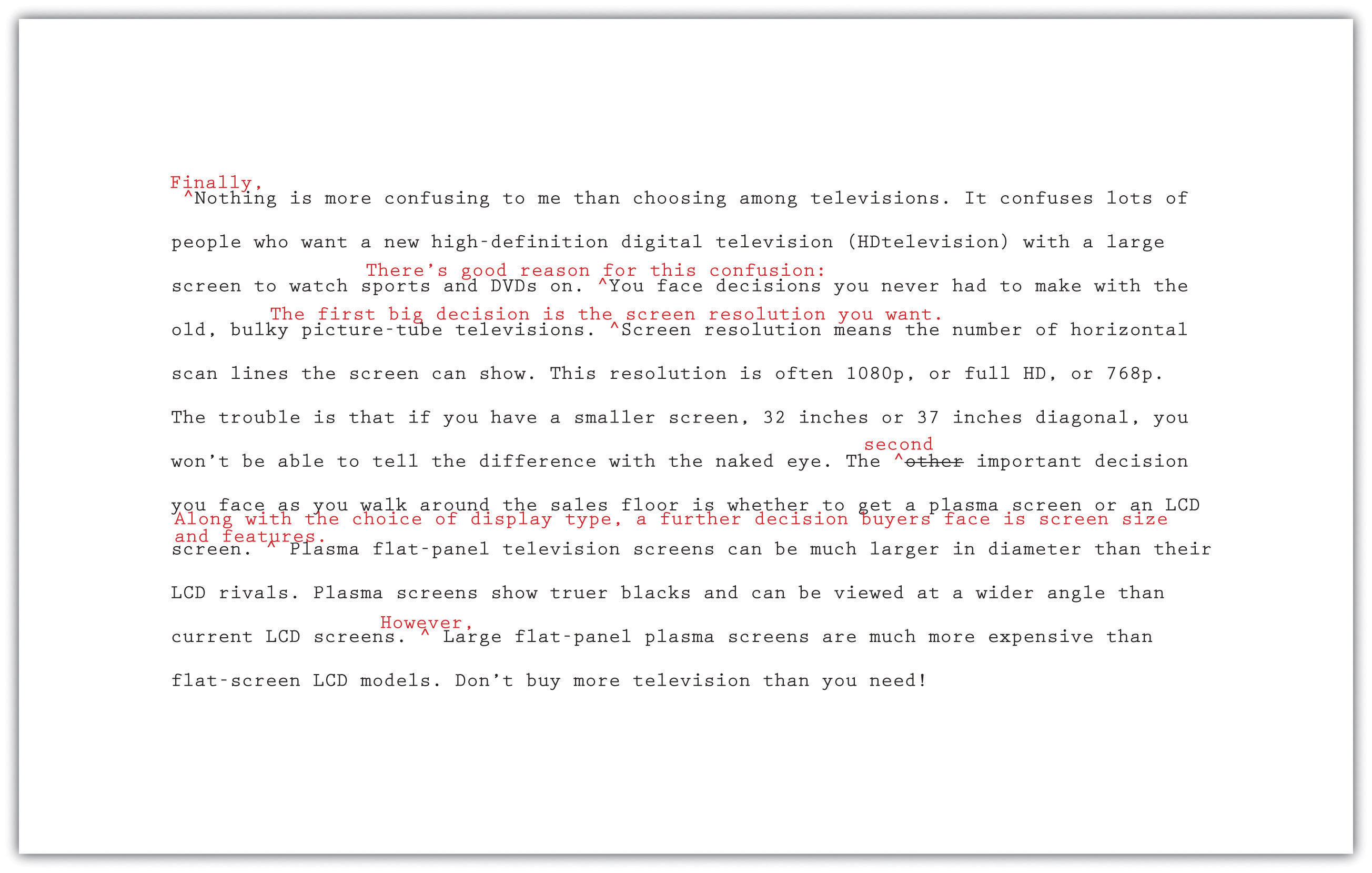

After Maria revised for unity, she next examined her paragraph about televisions to check for coherence. She looked for places where she needed to add a transition or perhaps reword the text to make the flow of ideas clear. In the version that follows, she has already deleted the sentences that were off topic.

Many writers make their revisions on a printed copy and then transfer them to the version on-screen. They conventionally use a small arrow called a caret (^) to show where to insert an addition or correction.

Answer the following questions about Mariah’s revised paragraph.

Some writers are very methodical and painstaking when they write a first draft. Other writers unleash a lot of words in order to get out all that they feel they need to say. Do either of these composing styles match your style? Or is your composing style somewhere in between? No matter which description best fits you, the first draft of almost every piece of writing, no matter its author, can be made clearer and more concise.

If you have a tendency to write too much, you will need to look for unnecessary words. If you have a tendency to be vague or imprecise in your wording, you will need to find specific words to replace any overly general language.

Sometimes writers use too many words when fewer words will appeal more to their audience and better fit their purpose. Here are some common examples of wordiness to look for in your draft. Eliminating wordiness helps all readers, because it makes your ideas clear, direct, and straightforward.

Sentences that begin with There is or There are.

Wordy: There are two major experiments that the Biology Department sponsors.

Revised: The Biology Department sponsors two major experiments.

Sentences with unnecessary modifiers.

Wordy: Two extremely famous and well-known consumer advocates spoke eloquently in favor of the proposed important legislation.

Revised: Two well-known consumer advocates spoke in favor of the proposed legislation.

Sentences with deadwood phrases that add little to the meaning. Be judicious when you use phrases such as in terms of, with a mind to, on the subject of, as to whether or not, more or less, as far as…is concerned, and similar expressions. You can usually find a more straightforward way to state your point.

Wordy: As a world leader in the field of green technology, the company plans to focus its efforts in the area of geothermal energy.

A report as to whether or not to use geysers as an energy source is in the process of preparation.

Revised: As a world leader in green technology, the company plans to focus on geothermal energy.

A report about using geysers as an energy source is in preparation.

Sentences in the passive voice or with forms of the verb to be. Sentences with passive-voice verbs often create confusion, because the subject of the sentence does not perform an action. Sentences are clearer when the subject of the sentence performs the action and is followed by a strong verb. Use strong active-voice verbs in place of forms of to be, which can lead to wordiness. Avoid passive voice when you can.

Wordy: It might perhaps be said that using a GPS device is something that is a benefit to drivers who have a poor sense of direction.

Revised: Using a GPS device benefits drivers who have a poor sense of direction.

Sentences with constructions that can be shortened.

Wordy: The e-book reader, which is a recent invention, may become as commonplace as the cell phone.

My over-sixty uncle bought an e-book reader, and his wife bought an e-book reader, too.

Revised: The e-book reader, a recent invention, may become as commonplace as the cell phone.

My over-sixty uncle and his wife both bought e-book readers.

Now return once more to the first draft of the essay you have been revising. Check it for unnecessary words. Try making your sentences as concise as they can be.

Most college essays should be written in formal English suitable for an academic situation. Follow these principles to be sure that your word choice is appropriate. For more information about word choice, see Chapter 4 "Working with Words: Which Word Is Right?".

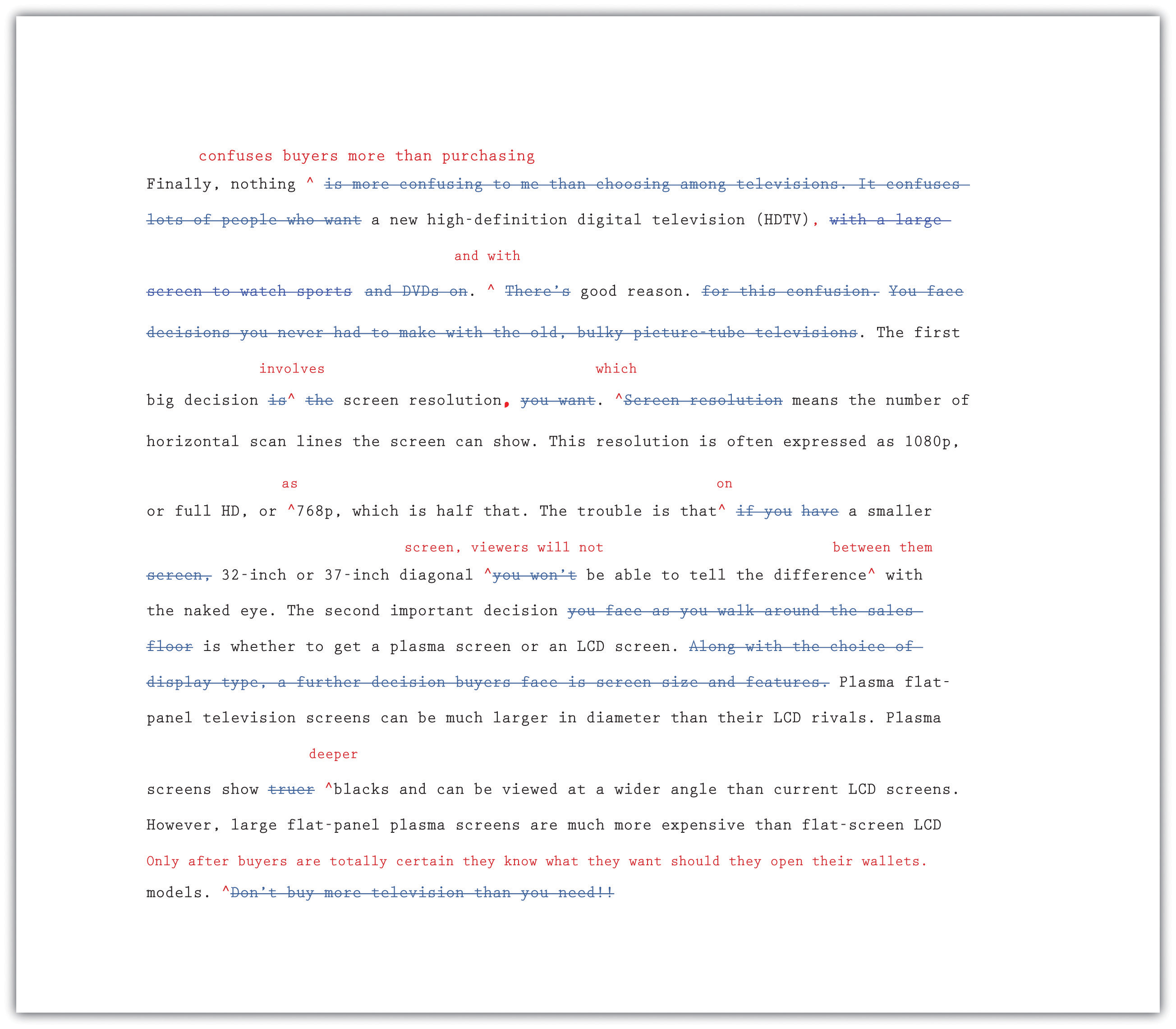

Now read the revisions Mariah made to make her third paragraph clearer and more concise. She has already incorporated the changes she made to improve unity and coherence.

Answer the following questions about Mariah’s revised paragraph:

After working so closely with a piece of writing, writers often need to step back and ask for a more objective reader. What writers most need is feedback from readers who can respond only to the words on the page. When they are ready, writers show their drafts to someone they respect and who can give an honest response about its strengths and weaknesses.

You, too, can ask a peer to read your draft when it is ready. After evaluating the feedback and assessing what is most helpful, the reader’s feedback will help you when you revise your draft. This process is called peer reviewThe process in which a writer allows a peer to read and evaluate a draft..

You can work with a partner in your class and identify specific ways to strengthen each other’s essays. Although you may be uncomfortable sharing your writing at first, remember that each writer is working toward the same goal: a final draft that fits the audience and the purpose. Maintaining a positive attitude when providing feedback will put you and your partner at ease. The box that follows provides a useful framework for the peer review session.

Title of essay: ____________________________________________

Date: ____________________________________________

Writer’s name: ____________________________________________

Peer reviewer’s name: _________________________________________

These three points struck me as your strongest:

Point: ____________________________________________

Why: ____________________________________________

Point: ____________________________________________

Why: ____________________________________________

Point: ____________________________________________

Why: ____________________________________________

These places in your essay are not clear to me:

Where: ____________________________________________

Needs improvement because__________________________________________

Where: ____________________________________________

Needs improvement because ____________________________________________

Where: ____________________________________________

Needs improvement because ____________________________________________

One of the reasons why word-processing programs build in a reviewing feature is that workgroups have become a common feature in many businesses. Writing is often collaborative, and the members of a workgroup and their supervisors often critique group members’ work and offer feedback that will lead to a better final product.

Exchange essays with a classmate and complete a peer review of each other’s draft in progress. Remember to give positive feedback and to be courteous and polite in your responses. Focus on providing one positive comment and one question for more information to the author.

The purpose of peer feedback is to receive constructive criticism of your essay. Your peer reviewer is your first real audience, and you have the opportunity to learn what confuses and delights a reader so that you can improve your work before sharing the final draft with a wider audience (or your intended audience).

It may not be necessary to incorporate every recommendation your peer reviewer makes. However, if you start to observe a pattern in the responses you receive from peer reviewers, you might want to take that feedback into consideration in future assignments. For example, if you read consistent comments about a need for more research, then you may want to consider including more research in future assignments.

You might get feedback from more than one reader as you share different stages of your revised draft. In this situation, you may receive feedback from readers who do not understand the assignment or who lack your involvement with and enthusiasm for it.

You need to evaluate the responses you receive according to two important criteria:

Then, using these standards, accept or reject revision feedback.

Work with two partners. Go back to Note 8.81 "Exercise 4" in this lesson and compare your responses to Activity A, about Mariah’s paragraph, with your partners’. Recall Mariah’s purpose for writing and her audience. Then, working individually, list where you agree and where you disagree about revision needs.

If you have been incorporating each set of revisions as Mariah has, you have produced multiple drafts of your writing. So far, all your changes have been content changes. Perhaps with the help of peer feedback, you have made sure that you sufficiently supported your ideas. You have checked for problems with unity and coherence. You have examined your essay for word choice, revising to cut unnecessary words and to replace weak wording with specific and appropriate wording.

The next step after revising the content is editing. When you edit, you examine the surface features of your text. You examine your spelling, grammar, usage, and punctuation. You also make sure you use the proper format when creating your finished assignment.

Editing often takes time. Budgeting time into the writing process allows you to complete additional edits after revising. Editing and proofreading your writing helps you create a finished work that represents your best efforts. Here are a few more tips to remember about your readers:

The first section of this book offers a useful review of grammar, mechanics, and usage. Use it to help you eliminate major errors in your writing and refine your understanding of the conventions of language. Do not hesitate to ask for help, too, from peer tutors in your academic department or in the college’s writing lab. In the meantime, use the checklist to help you edit your writing.

Editing Your Writing

Grammar

Sentence Structure

Punctuation

Mechanics and Usage

Be careful about relying too much on spelling checkers and grammar checkers. A spelling checker cannot recognize that you meant to write principle but wrote principal instead. A grammar checker often queries constructions that are perfectly correct. The program does not understand your meaning; it makes its check against a general set of formulas that might not apply in each instance. If you use a grammar checker, accept the suggestions that make sense, but consider why the suggestions came up.

Proofreading requires patience; it is very easy to read past a mistake. Set your paper aside for at least a few hours, if not a day or more, so your mind will rest. Some professional proofreaders read a text backward so they can concentrate on spelling and punctuation. Another helpful technique is to slowly read a paper aloud, paying attention to every word, letter, and punctuation mark.

If you need additional proofreading help, ask a reliable friend, a classmate, or a peer tutor to make a final pass on your paper to look for anything you missed.

Remember to use proper format when creating your finished assignment. Sometimes an instructor, a department, or a college will require students to follow specific instructions on titles, margins, page numbers, or the location of the writer’s name. These requirements may be more detailed and rigid for research projects and term papers, which often observe the American Psychological Association (APA) or Modern Language Association (MLA) style guides, especially when citations of sources are included.

To ensure the format is correct and follows any specific instructions, make a final check before you submit an assignment.

With the help of the checklist, edit and proofread your essay.

Write a thesis statement and a formal sentence outline for an essay about the writing process. Include separate paragraphs for prewriting, drafting, and revising and editing. Your audience will be a general audience of educated adults who are unfamiliar with how writing is taught at the college level. Your purpose is to explain the stages of the writing process so that readers will understand its benefits.

Collaboration

Please share with a classmate and compare your answers.