Like the group 14 elements, the lightest member of group 15, nitrogen, is found in nature as the free element, and the heaviest elements have been known for centuries because they are easily isolated from their ores.

Antimony (Sb) was probably the first of the pnicogens to be obtained in elemental form and recognized as an element. Its atomic symbol comes from its Roman name: stibium. It is found in stibnite (Sb2S3), a black mineral that has been used as a cosmetic (an early form of mascara) since biblical times, and it is easily reduced to the metal in a charcoal fire (Figure 22.10 "The Ancient Egyptians Used Finely Ground Antimony Sulfide for Eye Makeup"). The Egyptians used antimony to coat copper objects as early as the third millennium BC, and antimony is still used in alloys to improve the tonal quality of bells.

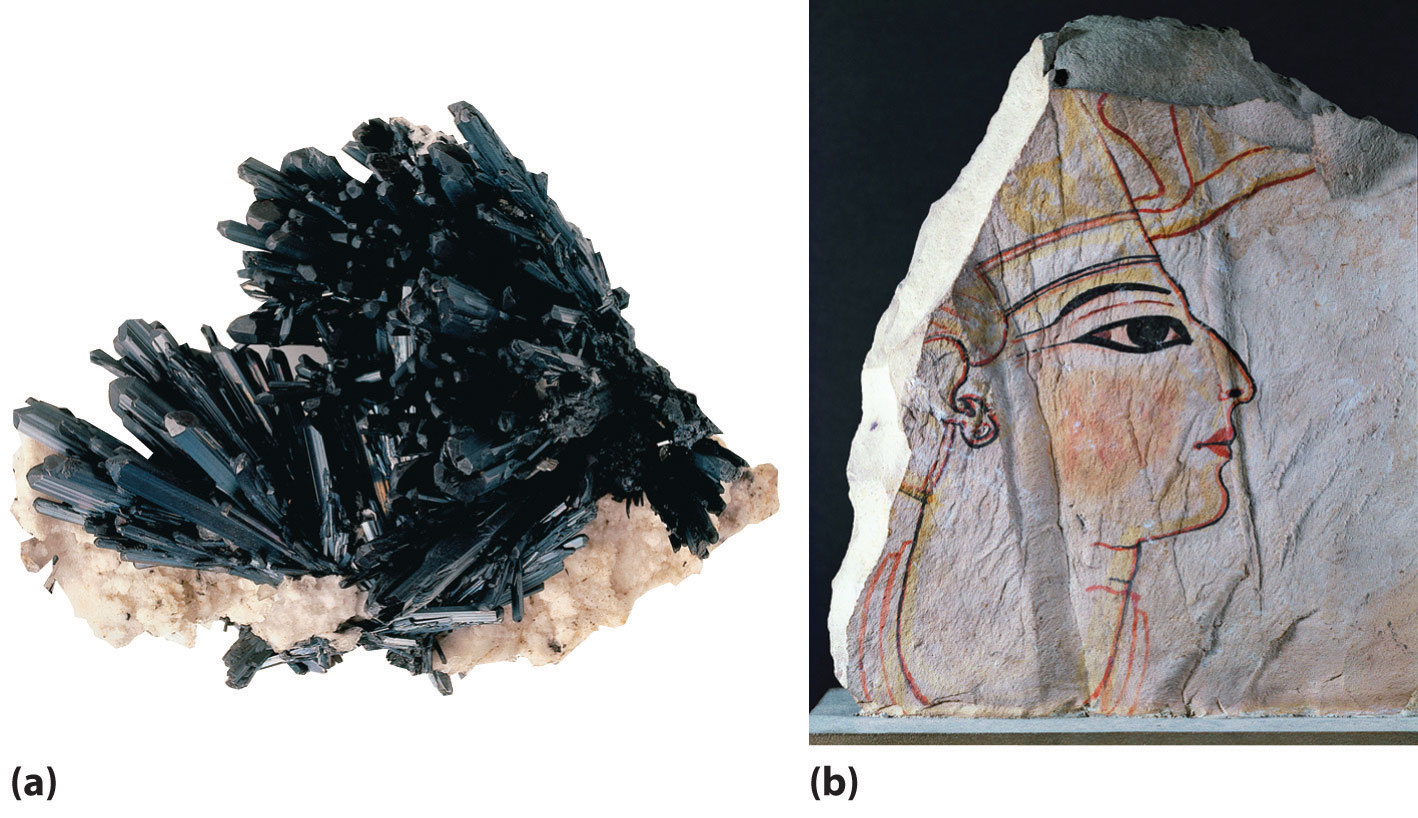

Figure 22.10 The Ancient Egyptians Used Finely Ground Antimony Sulfide for Eye Makeup

(a) Crystals of the soft black mineral stibnite (Sb2S3) on a white mineral matrix. (b) A fragment of an Egyptian painting on limestone from the 16th–13th centuries BC shows the use of ground stibnite (“kohl”) as black eye shadow. Small vases of ground stibnite have been found among the funeral goods buried with Egyptian pharaohs.

In the form of its yellow sulfide ore, orpiment (As2S3), arsenic (As) has been known to physicians and professional assassins since ancient Greece, although elemental arsenic was not isolated until centuries later. The history of bismuth (Bi), in contrast, is more difficult to follow because early alchemists often confused it with other metals, such as lead, tin, antimony, and even silver (due to its slightly pinkish-white luster). Its name comes from the old German wismut, meaning “white metal.” Bismuth was finally isolated in the 15th century, and it was used to make movable type for printing shortly after the invention of the Gutenberg printing process in 1440. Bismuth is used in printing because it is one of the few substances known whose solid state is less dense than the liquid. Consequently, its alloys expand as they cool, filling a mold completely and producing crisp, clear letters for typesetting.

Phosphorus was discovered in 1669 by the German alchemist Hennig Brandt, who was looking for the “philosophers’ stone,” a mythical substance capable of converting base metals to silver or gold. Believing that human urine was the source of the key ingredient, Brandt obtained several dozen buckets of urine, which he allowed to putrefy. The urine was distilled to dryness at high temperature and then condensed; the last fumes were collected under water, giving a waxy white solid that had unusual properties. For example, it glowed in the dark and burst into flames when removed from the water. (Unfortunately for Brandt, however, it did not turn lead into gold.) The element was given its current name (from the Greek phos, meaning “light,” and phoros, meaning “bringing”) in the 17th century. For more than a century, the only way to obtain phosphorus was the distillation of urine, but in 1769 it was discovered that phosphorus could be obtained more easily from bones. During the 19th century, the demand for phosphorus for matches was so great that battlefields and paupers’ graveyards were systematically scavenged for bones. Early matches were pieces of wood coated with elemental phosphorus that were stored in an evacuated glass tube and ignited when the tube was broken (which could cause unfortunate accidents if the matches were kept in a pocket!).

Unfortunately, elemental phosphorus is volatile and highly toxic. It is absorbed by the teeth and destroys bone in the jaw, leading to a painful and fatal condition called “phossy jaw,” which for many years was accepted as an occupational hazard of working in the match industry.

Although nitrogen is the most abundant element in the atmosphere, it was the last of the pnicogens to be obtained in pure form. In 1772, Daniel Rutherford, working with Joseph Black (who discovered CO2), noticed that a gas remained when CO2 was removed from a combustion reaction. Antoine Lavoisier called the gas azote, meaning “no life,” because it did not support life. When it was discovered that the same element was also present in nitric acid and nitrate salts such as KNO3 (nitre), it was named nitrogen. About 90% of the nitrogen produced today is used to provide an inert atmosphere for processes or reactions that are oxygen sensitive, such as the production of steel, petroleum refining, and the packaging of foods and pharmaceuticals.

Because the atmosphere contains several trillion tons of elemental nitrogen with a purity of about 80%, it is a huge source of nitrogen gas. Distillation of liquefied air yields nitrogen gas that is more than 99.99% pure, but small amounts of very pure nitrogen gas can be obtained from the thermal decomposition of sodium azide:

Equation 22.28

In contrast, Earth’s crust is relatively poor in nitrogen. The only important nitrogen ores are large deposits of KNO3 and NaNO3 in the deserts of Chile and Russia, which were apparently formed when ancient alkaline lakes evaporated. Consequently, virtually all nitrogen compounds produced on an industrial scale use atmospheric nitrogen as the starting material. Phosphorus, which constitutes only about 0.1% of Earth’s crust, is much more abundant in ores than nitrogen. Like aluminum and silicon, phosphorus is always found in combination with oxygen, and large inputs of energy are required to isolate it.

The other three pnicogens are much less abundant: arsenic is found in Earth’s crust at a concentration of about 2 ppm, antimony is an order of magnitude less abundant, and bismuth is almost as rare as gold. All three elements have a high affinity for the chalcogens and are usually found as the sulfide ores (M2S3), often in combination with sulfides of other heavy elements, such as copper, silver, and lead. Hence a major source of antimony and bismuth is flue dust obtained by smelting the sulfide ores of the more abundant metals.

In group 15, as elsewhere in the p block, we see large differences between the lightest element (N) and its congeners in size, ionization energy, electron affinity, and electronegativity (Table 22.3 "Selected Properties of the Group 15 Elements"). The chemical behavior of the elements can be summarized rather simply: nitrogen and phosphorus behave chemically like nonmetals, arsenic and antimony behave like semimetals, and bismuth behaves like a metal. With their ns2np3 valence electron configurations, all form compounds by losing either the three np valence electrons to form the +3 oxidation state or the three np and the two ns valence electrons to give the +5 oxidation state, whose stability decreases smoothly from phosphorus to bismuth. In addition, the relatively large magnitude of the electron affinity of the lighter pnicogens enables them to form compounds in the −3 oxidation state (such as NH3 and PH3), in which three electrons are formally added to the neutral atom to give a filled np subshell. Nitrogen has the unusual ability to form compounds in nine different oxidation states, including −3, +3, and +5. Because neutral covalent compounds of the trivalent pnicogens contain a lone pair of electrons on the central atom, they tend to behave as Lewis bases.

Table 22.3 Selected Properties of the Group 15 Elements

| Property | Nitrogen | Phosphorus | Arsenic | Antimony | Bismuth |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| atomic symbol | N | P | As | Sb | Bi |

| atomic number | 7 | 15 | 33 | 51 | 83 |

| atomic mass (amu) | 14.01 | 30.97 | 74.92 | 121.76 | 209.98 |

| valence electron configuration* | 2s22p3 | 3s23p3 | 4s24p3 | 5s25p3 | 6s26p3 |

| melting point/boiling point (°C) | −210/−196 | 44.15/281c | 817 (at 3.70 MPa)/603 (sublimes)† | 631/1587 | 271/1564 |

| density (g/cm3) at 25°C | 1.15 | 1.82† | 5.75‡ | 6.68 | 9.79 |

| atomic radius (pm) | 56 | 98 | 114 | 133 | 143 |

| first ionization energy (kJ/mol) | 1402 | 1012 | 945 | 831 | 703 |

| common oxidation state(s) | −3 to +5 | +5, +3, −3 | +5, +3 | +5, +3 | +3 |

| ionic radius (pm)§ | 146 (−3), 16 (+3) | 212 (−3), 44 (+3) | 58 (+3) | 76 (+3), 60 (+5) | 103 (+3) |

| electron affinity (kJ/mol) | 0 | −72 | −78 | −101 | −91 |

| electronegativity | 3.0 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 2.1 | 1.9 |

| standard reduction potential (E°, V) (EV → EIII in acidic solution)|| | +0.93 | −0.28 | +0.56 | +0.65 | — |

| product of reaction with O2 | NO2, NO | P4O6, P4O10 | As4O6 | Sb2O5 | Bi2O3 |

| type of oxide | acidic (NO2), neutral (NO, N2O) | acidic | acidic | amphoteric | basic |

| product of reaction with N2 | — | none | none | none | none |

| product of reaction with X2 | none | PX3, PX5 | AsF5, AsX3 | SbF5, SbCl5, SbBr3, SbI3 | BiF5, BiX3 |

| product of reaction with H2 | none | none | none | none | none |

| *The configuration shown does not include filled d and f subshells. | |||||

| †For white phosphorus. | |||||

| ‡For gray arsenic. | |||||

| §The values cited are for six-coordinate ions in the indicated oxidation states. The N5+, P5+, and As5+ ions are not known species. | |||||

| ||The chemical form of the elements in these oxidation states varies considerably. For N, the reaction is NO3− + 3H+ + 2e− → HNO2 + H2O; for P and As, it is H3EO4 + 2H+ + 2e− → H3EO3 + H2O; and for Sb it is Sb2O5 + 4e− + 10H+ → 2Sb3+ + 5H2O. | |||||

In group 15, the stability of the +5 oxidation state decreases from P to Bi.

Because neutral covalent compounds of the trivalent group 15 elements have a lone pair of electrons on the central atom, they tend to be Lewis bases.

Like carbon, nitrogen has four valence orbitals (one 2s and three 2p), so it can participate in at most four electron-pair bonds by using sp3 hybrid orbitals. Unlike carbon, however, nitrogen does not form long chains because of repulsive interactions between lone pairs of electrons on adjacent atoms. These interactions become important at the shorter internuclear distances encountered with the smaller, second-period elements of groups 15, 16, and 17. (For more information on internuclear distance, see Chapter 7 "The Periodic Table and Periodic Trends", Section 7.2 "Sizes of Atoms and Ions" and Chapter 8 "Ionic versus Covalent Bonding", Section 8.2 "Ionic Bonding".) Stable compounds with N–N bonds are limited to chains of no more than three N atoms, such as the azide ion (N3−).

Nitrogen is the only pnicogen that normally forms multiple bonds with itself and other second-period elements, using π overlap of adjacent np orbitals. Thus the stable form of elemental nitrogen is N2, whose N≡N bond is so strong (DN≡N = 942 kJ/mol) compared with the N–N and N=N bonds (DN–N = 167 kJ/mol; DN=N = 418 kJ/mol) that all compounds containing N–N and N=N bonds are thermodynamically unstable with respect to the formation of N2. In fact, the formation of the N≡N bond is so thermodynamically favored that virtually all compounds containing N–N bonds are potentially explosive.

Again in contrast to carbon, nitrogen undergoes only two important chemical reactions at room temperature: it reacts with metallic lithium to form lithium nitride, and it is reduced to ammonia by certain microorganisms. (For more information lithium, see Chapter 21 "Periodic Trends and the ".) At higher temperatures, however, N2 reacts with more electropositive elements, such as those in group 13, to give binary nitrides, which range from covalent to ionic in character. Like the corresponding compounds of carbon, binary compounds of nitrogen with oxygen, hydrogen, or other nonmetals are usually covalent molecular substances.

Few binary molecular compounds of nitrogen are formed by direct reaction of the elements. At elevated temperatures, N2 reacts with H2 to form ammonia, with O2 to form a mixture of NO and NO2, and with carbon to form cyanogen (N≡C–C≡N); elemental nitrogen does not react with the halogens or the other chalcogens. Nonetheless, all the binary nitrogen halides (NX3) are known. Except for NF3, all are toxic, thermodynamically unstable, and potentially explosive, and all are prepared by reacting the halogen with NH3 rather than N2. Both nitrogen monoxide (NO) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2) are thermodynamically unstable, with positive free energies of formation. Unlike NO, NO2 reacts readily with excess water, forming a 1:1 mixture of nitrous acid (HNO2) and nitric acid (HNO3):

Equation 22.29

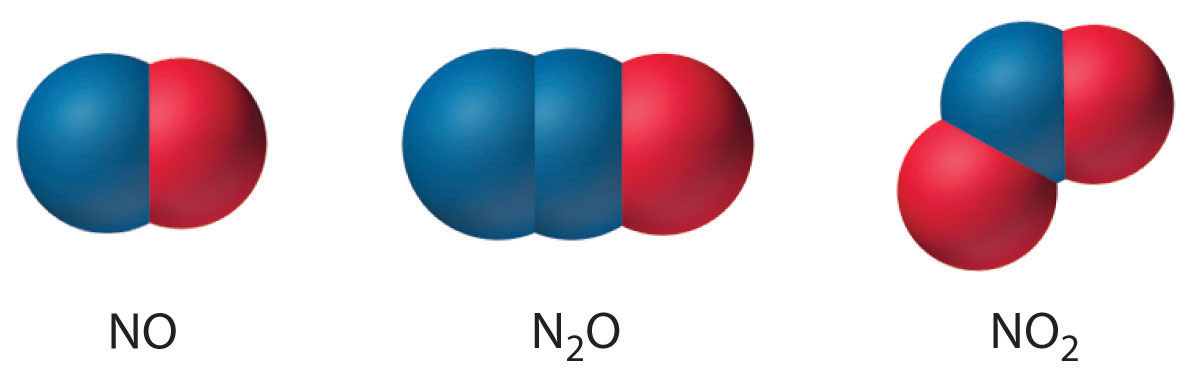

2NO2(g) + H2O(l) → HNO2(aq) + HNO3(aq)Nitrogen also forms N2O (dinitrogen monoxide, or nitrous oxide), a linear molecule that is isoelectronic with CO2 and can be represented as −N=N+=O. Like the other two oxides of nitrogen, nitrous oxide is thermodynamically unstable. The structures of the three common oxides of nitrogen are as follows:

Few binary molecular compounds of nitrogen are formed by the direct reaction of the elements.

At elevated temperatures, nitrogen reacts with highly electropositive metals to form ionic nitrides, such as Li3N and Ca3N2. These compounds consist of ionic lattices formed by Mn+ and N3− ions. Just as boron forms interstitial borides and carbon forms interstitial carbides, with less electropositive metals nitrogen forms a range of interstitial nitrides, in which nitrogen occupies holes in a close-packed metallic structure. Like the interstitial carbides and borides, these substances are typically very hard, high-melting materials that have metallic luster and conductivity.

Nitrogen also reacts with semimetals at very high temperatures to produce covalent nitrides, such as Si3N4 and BN, which are solids with extended covalent network structures similar to those of graphite or diamond. Consequently, they are usually high melting and chemically inert materials.

Ammonia (NH3) is one of the few thermodynamically stable binary compounds of nitrogen with a nonmetal. It is not flammable in air, but it burns in an O2 atmosphere:

Equation 22.30

4NH3(g) + 3O2(g) → 2N2(g) + 6H2O(g)About 10% of the ammonia produced annually is used to make fibers and plastics that contain amide bonds, such as nylons and polyurethanes, while 5% is used in explosives, such as ammonium nitrate, TNT (trinitrotoluene), and nitroglycerine. Large amounts of anhydrous liquid ammonia are used as fertilizer.

Nitrogen forms two other important binary compounds with hydrogen. Hydrazoic acid (HN3), also called hydrogen azide, is a colorless, highly toxic, and explosive substance. Hydrazine (N2H4) is also potentially explosive; it is used as a rocket propellant and to inhibit corrosion in boilers.

B, C, and N all react with transition metals to form interstitial compounds that are hard, high-melting materials.

For each reaction, explain why the given products form when the reactants are heated.

Given: balanced chemical equations

Asked for: why the given products form

Strategy:

Classify the type of reaction. Using periodic trends in atomic properties, thermodynamics, and kinetics, explain why the observed reaction products form.

Solution:

Exercise

Predict the product(s) of each reaction and write a balanced chemical equation for each reaction.

Answer:

Like the heavier elements of group 14, the heavier pnicogens form catenated compounds that contain only single bonds, whose stability decreases rapidly as we go down the group. For example, phosphorus exists as multiple allotropes, the most common of which is white phosphorus, which consists of P4 tetrahedra and behaves like a typical nonmetal. As is typical of a molecular solid, white phosphorus is volatile, has a low melting point (44.1°C), and is soluble in nonpolar solvents. It is highly strained, with bond angles of only 60°, which partially explains why it is so reactive and so easily converted to more stable allotropes. Heating white phosphorus for several days converts it to red phosphorus, a polymer that is air stable, virtually insoluble, denser than white phosphorus, and higher melting, properties that make it much safer to handle. A third allotrope of phosphorus, black phosphorus, is prepared by heating the other allotropes under high pressure; it is even less reactive, denser, and higher melting than red phosphorus. As expected from their structures, white phosphorus is an electrical insulator, and red and black phosphorus are semiconductors. The three heaviest pnicogens—arsenic, antimony, and bismuth—all have a metallic luster, but they are brittle (not ductile) and relatively poor electrical conductors.

As in group 14, the heavier group 15 elements form catenated compounds that contain only single bonds, whose stability decreases as we go down the group.

The reactivity of the heavier pnicogens decreases as we go down the column. Phosphorus is by far the most reactive of the pnicogens, forming binary compounds with every element in the periodic table except antimony, bismuth, and the noble gases. Phosphorus reacts rapidly with O2, whereas arsenic burns in pure O2 if ignited, and antimony and bismuth react with O2 only when heated. None of the pnicogens reacts with nonoxidizing acids such as aqueous HCl, but all dissolve in oxidizing acids such as HNO3. Only bismuth behaves like a metal, dissolving in HNO3 to give the hydrated Bi3+ cation.

The reactivity of the heavier group 15 elements decreases as we go down the column.

The heavier pnicogens can use energetically accessible 3d, 4d, or 5d orbitals to form dsp3 or d2sp3 hybrid orbitals for bonding. Consequently, these elements often have coordination numbers of 5 or higher. Phosphorus and arsenic form halides (e.g., AsCl5) that are generally covalent molecular species and behave like typical nonmetal halides, reacting with water to form the corresponding oxoacids (in this case, H3AsO4). All the pentahalides are potent Lewis acids that can expand their coordination to accommodate the lone pair of a Lewis base:

Equation 22.31

AsF5(soln) + F−(soln) → AsF6−(soln)In contrast, bismuth halides have extended lattice structures and dissolve in water to produce hydrated ions, consistent with the stronger metallic character of bismuth.

Except for BiF3, which is essentially an ionic compound, the trihalides are volatile covalent molecules with a lone pair of electrons on the central atom. Like the pentahalides, the trihalides react rapidly with water. In the cases of phosphorus and arsenic, the products are the corresponding acids, H3PO3 and H3AsO3, where E is P or As:

Equation 22.32

EX3(l) + 3H2O(l) → H3EO3(aq) + 3HX(aq)Phosphorus halides are also used to produce insecticides, flame retardants, and plasticizers.

With energetically accessible d orbitals, phosphorus and, to a lesser extent, arsenic are able to form π bonds with second-period atoms such as N and O. This effect is even more important for phosphorus than for silicon, resulting in very strong P–O bonds and even stronger P=O bonds. The first four elements in group 15 also react with oxygen to produce the corresponding oxide in the +3 oxidation state. Of these oxides, P4O6 and As4O6 have cage structures formed by inserting an oxygen atom into each edge of the P4 or As4 tetrahedron (part (a) in Figure 22.11 "The Structures of Some Cage Compounds of Phosphorus"), and they behave like typical nonmetal oxides. For example, P4O6 reacts with water to form phosphorous acid (H3PO3). Consistent with its position between the nonmetal and metallic oxides, Sb4O6 is amphoteric, dissolving in either acid or base. In contrast, Bi2O3 behaves like a basic metallic oxide, dissolving in acid to give solutions that contain the hydrated Bi3+ ion. The two least metallic elements of the heavier pnicogens, phosphorus and arsenic, form very stable oxides with the formula E4O10 in the +5 oxidation state (part (b) in Figure 22.11 "The Structures of Some Cage Compounds of Phosphorus"). In contrast, Bi2O5 is so unstable that there is no absolute proof it exists.

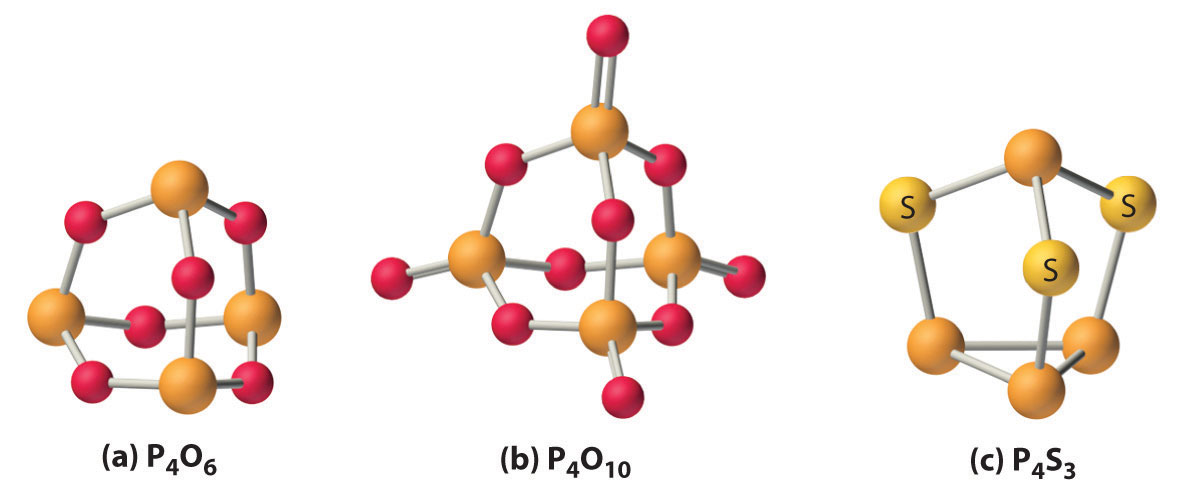

Figure 22.11 The Structures of Some Cage Compounds of Phosphorus

(a, b) The structures of P4O6 and P4O10 are both derived from the structure of white phosphorus (P4) by inserting an oxygen atom into each of the six edges of the P4 tetrahedron; P4O10 contains an additional terminal oxygen atom bonded to each phosphorus atom. (c) The structure of P4S3 is also derived from the structure of P4 by inserting three sulfur atoms into three adjacent edges of the tetrahedron.

The heavier pnicogens form sulfides that range from molecular species with three-dimensional cage structures, such as P4S3 (part (c) in Figure 22.11 "The Structures of Some Cage Compounds of Phosphorus"), to layered or ribbon structures, such as Sb2S3 and Bi2S3, which are semiconductors. Reacting the heavier pnicogens with metals produces substances whose properties vary with the metal content. Metal-rich phosphides (such as M4P) are hard, high-melting, electrically conductive solids with a metallic luster, whereas phosphorus-rich phosphides (such as MP15) are lower melting and less thermally stable because they contain catenated Pn units. Many organic or organometallic compounds of the heavier pnicogens containing one to five alkyl or aryl groups are also known. Because of the decreasing strength of the pnicogen–carbon bond, their thermal stability decreases from phosphorus to bismuth.

Phosphorus has the greatest ability to form π bonds with elements such as O, N, and C.

The thermal stability of organic or organometallic compounds of group 15 decreases down the group due to the decreasing strength of the pnicogen–carbon bond.

For each reaction, explain why the given products form.

Given: balanced chemical equations

Asked for: why the given products form

Strategy:

Classify the type of reaction. Using periodic trends in atomic properties, thermodynamics, and kinetics, explain why the reaction products form.

Solution:

Exercise

Predict the products of each reaction and write a balanced chemical equation for each reaction.

Answer:

In group 15, nitrogen and phosphorus behave chemically like nonmetals, arsenic and antimony behave like semimetals, and bismuth behaves like a metal. Nitrogen forms compounds in nine different oxidation states. The stability of the +5 oxidation state decreases from phosphorus to bismuth because of the inert-pair effect. Due to their higher electronegativity, the lighter pnicogens form compounds in the −3 oxidation state. Because of the presence of a lone pair of electrons on the pnicogen, neutral covalent compounds of the trivalent pnicogens are Lewis bases. Nitrogen does not form stable catenated compounds because of repulsions between lone pairs of electrons on adjacent atoms, but it does form multiple bonds with other second-period atoms. Nitrogen reacts with electropositive elements to produce solids that range from covalent to ionic in character. Reaction with electropositive metals produces ionic nitrides, reaction with less electropositive metals produces interstitial nitrides, and reaction with semimetals produces covalent nitrides. The reactivity of the pnicogens decreases with increasing atomic number. Compounds of the heavier pnicogens often have coordination numbers of 5 or higher and use dsp3 or d2sp3 hybrid orbitals for bonding. Because phosphorus and arsenic have energetically accessible d orbitals, these elements form π bonds with second-period atoms such as O and N. Phosphorus reacts with metals to produce phosphides. Metal-rich phosphides are hard, high-melting, electrically conductive solids with metallic luster, whereas phosphorus-rich phosphides, which contain catenated phosphorus units, are lower melting and less thermally stable.

Nitrogen is the first diatomic molecule in the second period of elements. Why is N2 the most stable form of nitrogen? Draw its Lewis electron structure. What hybrid orbitals are used to describe the bonding in this molecule? Is the molecule polar?

The polymer (SN)n has metallic luster and conductivity. Are the constituent elements in this polymer metals or nonmetals? Why does the polymer have metallic properties?

Except for NF3, all the halides of nitrogen are unstable. Explain why NF3 is stable.

Which of the group 15 elements forms the most stable compounds in the +3 oxidation state? Explain why.

Phosphorus and arsenic react with the alkali metals to produce salts with the composition M3Z11. Compare these products with those produced by reaction of P and As with the alkaline earth metals. What conclusions can you draw about the types of structures favored by the heavier elements in this part of the periodic table?

PF3 reacts with F2 to produce PF5, which in turn reacts with F− to give salts that contain the PF6− ion. In contrast, NF3 does not react with F2, even under extreme conditions; NF5 and the NF6− ion do not exist. Why?

Red phosphorus is safer to handle than white phosphorus, reflecting their dissimilar properties. Given their structures, how do you expect them to compare with regard to reactivity, solubility, density, and melting point?

Bismuth oxalate [Bi2(C2O4)3] is a poison. Draw its structure and then predict its solubility in H2O, dilute HCl, and dilute HNO3. Predict its combustion products. Suggest a method to prepare bismuth oxalate from bismuth.

Small quantities of NO can be obtained in the laboratory by reaction of the iodide ion with acidic solutions of nitrite. Write a balanced chemical equation that represents this reaction.

Although pure nitrous acid is unstable, dilute solutions in water are prepared by adding nitrite salts to aqueous acid. Write a balanced chemical equation that represents this type of reaction.

Metallic versus nonmetallic behavior becomes apparent in reactions of the elements with an oxidizing acid, such as HNO3. Write balanced chemical equations for the reaction of each element of group 15 with nitric acid. Based on the products, predict which of these elements, if any, are metals and which, if any, are nonmetals.

Predict the product(s) of each reaction and then balance each chemical equation.

Write a balanced chemical equation to show how you would prepare each compound.

NaNO2(s) + HCl(aq) → HNO2(aq) + NaCl(aq)