Economists use the term equilibrium in the same way that the word is used in physics: to represent a steady state in which opposing forces are balanced so that the current state of the system tends to persist. In the context of supply and demand, equilibriumCondition that occurs when the pressure for higher prices is balanced by the pressure for lower prices so that the current rate of exchange between buyers and sellers persists. occurs when the pressure for higher prices is balanced by the pressure for lower prices, and so that rate of exchange between buyers and sellers persists.

When the current price is above the equilibrium price, the quantity supplied exceeds the quantity demanded, and some suppliers are unable to sell their goods because fewer units are purchased than are supplied. This condition, where the quantity supplied exceeds the quantity demanded, is called a surplusCondition in which the quantity supplied exceeds the quantity demanded.. The suppliers failing to sell have an incentive to offer their good at a slightly lower price—a penny less—to make a sale. Consequently, when there is a surplus, suppliers push prices down to increase sales. In the process, the fall in prices reduces the quantity supplied and increases the quantity demanded, thus eventually eliminating the surplus. That is, a surplus encourages price-cutting, which reduces the surplus, a process that ends only when the quantity supplied equals the quantity demanded.

Similarly, when the current price is lower than the equilibrium price, the quantity demanded exceeds the quantity supplied, and a shortageCondition in which the quantity demanded exceeds the quantity supplied. exists. In this case, some buyers fail to purchase, and these buyers have an incentive to offer a slightly higher price to make their desired purchase. Sellers are pleased to receive higher prices, which tends to put upward pressure on the price. The increase in price reduces the quantity demanded and increases the quantity supplied, thereby eliminating the shortage. Again, these adjustments in price persist until the quantity supplied equals the quantity demanded.

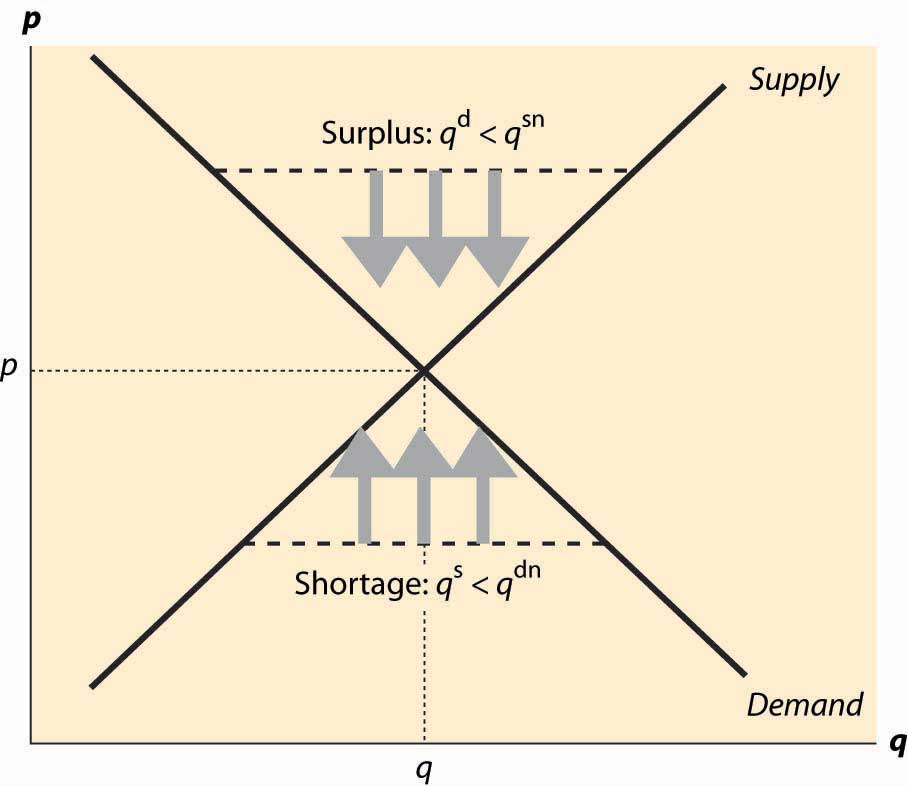

Figure 2.9 Equilibration

This logic, which is illustrated in Figure 2.9 "Equilibration", justifies the conclusion that the only equilibrium price is the price at which the quantity supplied equals the quantity demanded. Any other price will tend to rise in a shortage, or fall in a surplus, until supply and demand are balanced. In Figure 2.9 "Equilibration", a surplus arises at any price above the equilibrium price p*, because the quantity supplied qs is larger than the quantity demanded qd. The effect of the surplus—leading to sellers with excess inventory—induces price-cutting, which is illustrated using three arrows pointing down.

Similarly, when the price is below p*, the quantity supplied qs is less than the quantity demanded qd. This causes some buyers to fail to find goods, leading to higher asking prices and higher bid prices by buyers. The tendency for the price to rise is illustrated using three arrows pointing up. The only price that doesn’t lead to price changes is p*, the equilibrium price in which the quantity supplied equals the quantity demanded.

The logic of equilibrium in supply and demand is played out daily in markets all over the world—from stock, bond, and commodity markets with traders yelling to buy or sell, to Barcelona fish markets where an auctioneer helps the market find a price, to Istanbul’s gold markets, to Los Angeles’s real estate markets.

The equilibrium of supply and demand balances the quantity demanded and the quantity supplied so that there is no excess of either. Would it be desirable, from a social perspective, to force more trade or to restrain trade below this level?

There are circumstances where the equilibrium level of trade has harmful consequences, and such circumstances are considered in the chapter on externalities. However, provided that the only people affected by a transaction are the buyer and the seller, the equilibrium of supply and demand maximizes the total gains from trade.

This proposition is quite easy to see. To maximize the gains from trade, clearly the highest value buyers must get the goods. Otherwise, if a buyer that values the good less gets it over a buyer who values it more, then gains can arise from them trading. Similarly, the lowest-cost sellers must supply those goods; otherwise we can increase the gains from trade by replacing a higher-cost seller with a lower-cost seller. Thus, the only question is how many goods should be traded to maximize the gains from trade, since it will involve the lowest-cost suppliers selling to the highest-value buyers. Adding a trade increases the total gains from trade when that trade involves a buyer with value higher than the seller’s cost. Thus, the gains from trade are maximized by the set of transactions to the left of the equilibrium, with the high-value buyers buying from the low-cost sellers.

In the economist’s language, the equilibrium is efficientMaximizing the gains from trade under the assumption that the only people affected by any given transaction are the buyers and the seller. in that it maximizes the gains from trade under the assumption that the only people affected by any given transaction are the buyers and the seller.