Is price discrimination a good thing or a bad thing? It turns out that there is no definitive answer to this question. Instead, it depends on circumstances. We illustrate this conclusion with a pair of exercises.

This exercise illustrates a much more general proposition: If a price discriminating monopolist produces less than a nondiscriminating monopolist, then price discrimination reduces welfare. This proposition has an elementary proof. Consider the price discriminating monopolist’s sales, and then allow arbitrage. The arbitrage increases the gains from trade, since every transaction has gains from trade. Arbitrage, however, leads to a common price like that charged by a nondiscriminating monopolist. Thus, the only way that price discrimination can increase welfare is if it leads a seller to sell more output than he or she would otherwise. This is possible, as the next exercise shows.

In Exercise 2, we see that price discrimination that brings in a new group of customers may increase the gains from trade. Indeed, this example involves a Pareto improvement: The seller and Group 2 are better off, and Group 1 is no worse off, than without price discrimination. (A Pareto improvement requires that no one is worse off and at least one person is better off.)

Whether price discrimination increases the gains from trade overall depends on circumstances. However, it is worth remembering that people with lower incomes tend to have more elastic demand, and thus get lower prices under price discrimination than absent price discrimination. Consequently, a ban on price discrimination tends to hurt the poor and benefit the rich, no matter what the overall effect.

A common form of price discrimination is known as two-part pricingPrice discrimination featuring a fixed charge plus a marginal charge.. Two-part pricing usually involves a fixed charge and a marginal charge, and thus offers the ability for a seller to capture a portion of the consumer surplus. For example, electricity often comes with a fixed price per month and then a price per kilowatt-hour, which is two-part pricing. Similarly, long distance and cellular telephone companies charge a fixed fee per month, with a fixed number of “included” minutes, and a price per minute for additional minutes. Such contracts really involve three parts rather than two parts, but are similar in spirit.

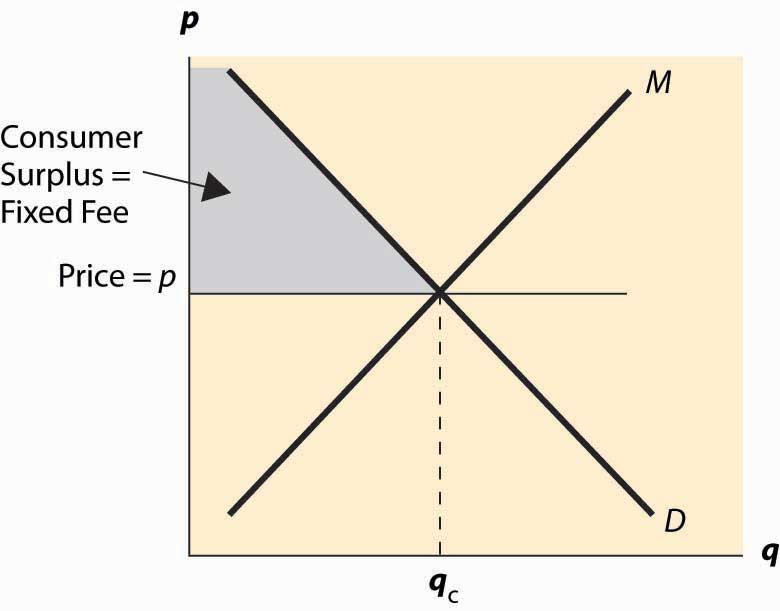

Figure 15.2 Two-part pricing

From the seller’s perspective, the ideal two-part price is to charge marginal cost plus a fixed charge equal to the customer’s consumer surplus, or perhaps a penny less. By setting price equal to marginal cost, the seller maximizes the gains from trade. By setting the fixed fee equal to consumer surplus, the seller captures the entire gains from trade. This is illustrated in Figure 15.2 "Two-part pricing".