After you have read this section, you should be able to answer the following questions:

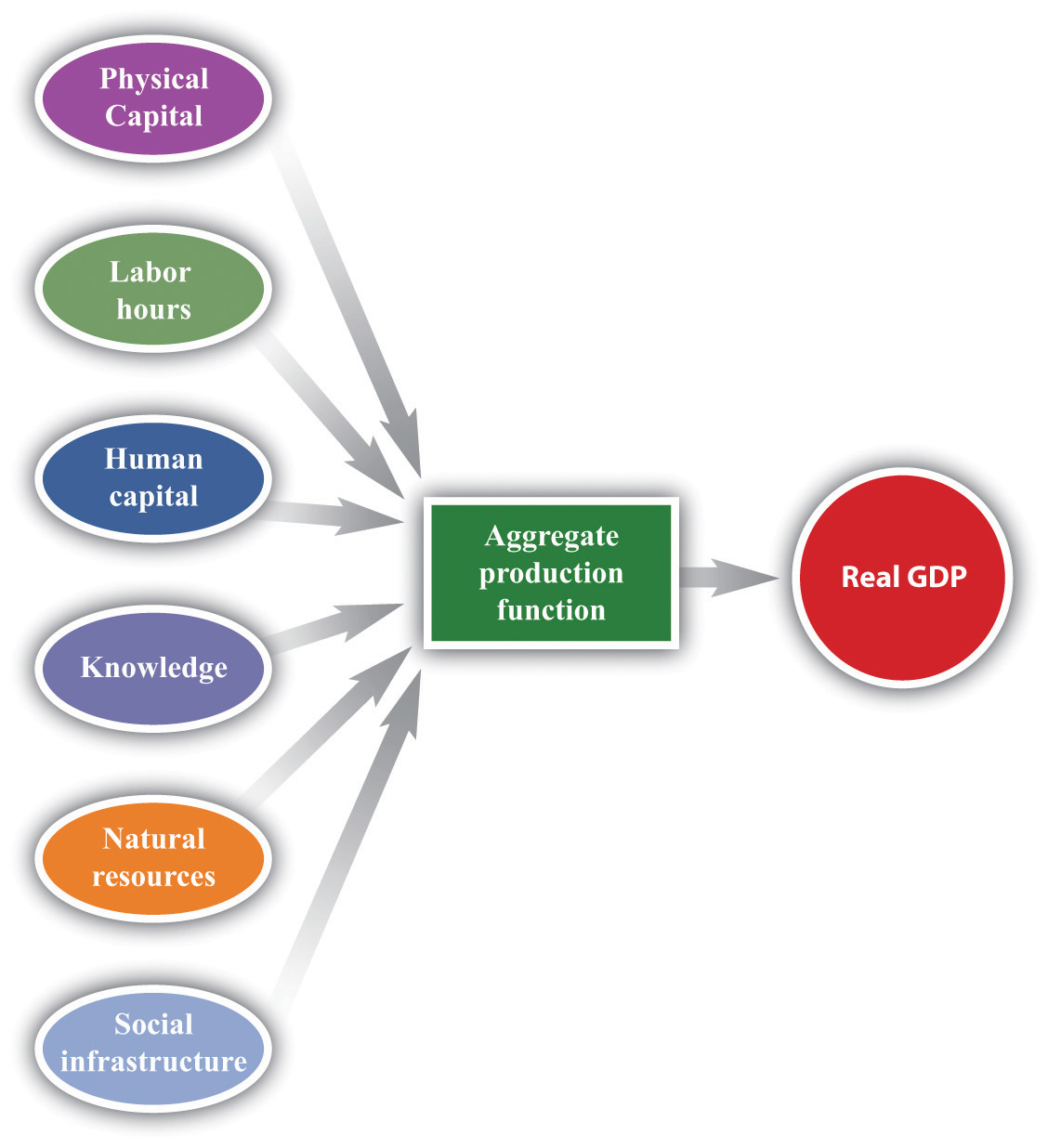

Economists analyze production in an economy by analogy to the production of output by a firm. Just as a firm takes inputs and transforms them into output, so also does the economy as a whole. We summarize the production capabilities of an economy with an aggregate production functionA combination of an economy’s physical capital stock, labor hours, human capital, knowledge, natural resources, and social infrastructure that produces output (real GDP)..

Toolkit: Section 16.15 "The Aggregate Production Function"

The aggregate production function describes how aggregate output (real gross domestic product [real GDP]A measure of production that has been corrected for any changes in overall prices.) in an economy depends on available inputs. The most important inputs are as follows:

Output increases whenever there is an increase in one of these inputs, all else being the same.

Physical capitalThe total amount of machines and production facilities used in production. refers to goods—such as factory buildings, machinery, and 18-wheel trucks—that have two essential features. First, capital goods are used in the production of other goods. The production of physical capital does not increase our well-being in and of itself. It allows us to produce more goods in the future, which permits us to enjoy more consumption at some future date. Second, capital goods are long lasting, which means we accumulate a capital stock over time. Capital goods are thus distinct from intermediate goods, which are fully used up in the production process.

The capital stockThe total amount of physical capital in an economy. of an economy is the total amount of physical capital in the economy. As well as factories and machines, the capital stock includes physical infrastructure—road networks, airports, telecommunications networks, and the like. These are capital goods that are available for multiple firms to use. Sometimes these goods are supplied by governments (roads, for example); sometimes they are provided by private firms (cellular telephone networks are an example). For brevity, we often simply refer to “capital” rather than “physical capital.” When you see the word capital appearing on its own in this book you should always understand it to mean physical capital.

Labor hoursThe total hours worked in an economy, measured as the number of people employed times the average hours they work. are the total number of hours worked in an economy. This depends on the size of the workforce and on how many hours are worked by each individual.We use the term workforce rather than labor force deliberately because the term labor force has a precise definition—those who are unemployed as well as those who are working. We want to include only those who are working because they are the ones supplying the labor hours that go into the production function. Chapter 8 "Jobs in the Macroeconomy" discusses this distinction in more detail.

Human capitalThe skills and knowledge that are embodied within workers. is the term that economists use for the skills and training of an economy’s workforce. It includes both formal education and on-the-job training. It likewise includes technical skills, such as those of a plumber, an electrician, or a software designer, and managerial skills, such as leadership and people management.

KnowledgeThe blueprints that describe a production process. is the information that is contained in books, software, or blueprints. It encompasses basic mathematics, such as calculus and the Pythagorean theorem, as well as more specific pieces of knowledge, such as the map of the human genome, the formula for Coca-Cola, or the instructions for building a space shuttle.

Natural resourcesOil, coal, and other mineral deposits; agricultural and forest lands; and other resources used in the production process. include land; oil and coal reserves; and other valuable resources, such as precious metals.

Social infrastructureThe general business climate, including any relevant features of the culture. refers to the legal, political, social, and cultural frameworks that exist in an economy. An economy with good social infrastructure is relatively free of corruption, has a functional and reliable legal system, and so on. Also included in social infrastructure are any relevant cultural variables. For example, it is sometimes argued that some societies are—for whatever reason—more entrepreneurial than others. As another example, the number of different languages that are spoken in a country influences GDP.

We show the production function schematically in Figure 5.2 "The Aggregate Production Function".

Figure 5.2 The Aggregate Production Function

The aggregate production function combines an economy’s physical capital stock, labor hours, human capital, knowledge, natural resources, and social infrastructure to produce output (real GDP).

The idea of the production function is simple: if we put more in, we get more out.

We call the extra output that we get from one more unit of an input, holding all other inputs fixed, the marginal productThe extra output obtained from one more unit of an input, holding all other inputs fixed. of that input. For example, the extra output we obtain from one more unit of capital is the marginal product of capitalThe extra output obtained from one more unit of capital., the extra output we get from one more unit of labor is the marginal product of laborThe amount of extra output produced from one extra hour of labor input., and so on.

Physical capital and labor hours are relatively straightforward to understand and measure. To measure labor hours, we simply count the number of workers and the number of hours worked by an average worker. Output increases if we have more workers or if they work longer hours. For simplicity, we imagine that all workers are identical. Aggregate differences in the type and the quality of labor are captured in our human capital variable. For physical capital, we similarly imagine that there are a number of identical machines (pizza ovens). Then, just as we measure labor as the number of worker hours, so also we could measure capital by the total number of machine hours.If this were literally true, we could measure capital stock by simply counting the number of machines in an economy. In reality, however, the measurement of capital stock is trickier. Researchers must add together the value of all the different pieces of capital in an economy. In practice, capital stock is usually measured indirectly by looking at the flow of additions to capital stock. We can produce more output by having more machines or by using each machine more intensively.

The other inputs that we listed—human capital, knowledge, social infrastructure, and natural resources—are trickier to define and much harder to quantify. Economists have used measures of educational attainment (e.g., the fraction of the population that completes high school) to compare human capital across countries.We use an index of human capital in Chapter 6 "Global Prosperity and Global Poverty". There are likewise some data that provide some indication of knowledge and social infrastructure—such as spending on research and development (R&D) and survey measures of perceived corruption.

The measurement of natural resources is problematic for different reasons. Land is evidently an input to production: factories must be put somewhere, and agriculture requires fields and orchards, so the value of land can be measured in principle. But what about reserves of oil or underground stocks of coal, uranium, or gold? First, such reserves or stocks contribute to real GDP only if they are extracted from the earth. An untapped oil field is part of a nation’s wealth but makes no contribution to current production. Second, it is very hard to measure such stocks, even in principle. For example, the amount of available oil reserves in an economy depends on mining and drilling technologies. Oil that could not have been extracted two decades ago is now available; it is likely that future advances in drilling techniques will further increase available reserves in the economy.

We simply accept that, as a practical matter, we cannot directly measure an economy’s knowledge, social infrastructure, and natural resources. As we see later in this chapter, however, there is a technique for indirectly measuring the combined influence of these inputs.

One thing might strike you as odd. Our description of production does not include as inputs the raw materials that go into production. The production process for a typical firm takes raw materials and transforms them into something more valuable. For example, a pizza restaurant buys flour, tomatoes, pepperoni, electricity, and so on, and transforms them into pizzas. The aggregate production function measures not the total value of these pizzas but the extra value that is added through the process of production. This equals the value of the pizzas minus the value of the raw materials. We take this approach to avoid double counting and be consistent with the way real GDP is actually measured.Reserves of natural resources are not counted as raw materials. The output of the mining sector is the value of the resources that have been extracted from the earth.

Table 5.1 "A Numerical Example of a Production Function" gives a numerical example of a production function. The first column lists the amount of output that can be produced from the inputs listed in the following columns.

Table 5.1 A Numerical Example of a Production Function

| Row | Output | Capital | Labor | Other Inputs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increasing Capital | ||||

| A | 100 | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| B | 126 | 2 | 1 | 100 |

| C | 144 | 3 | 1 | 100 |

| D | 159 | 4 | 1 | 100 |

| Increasing Labor | ||||

| E | 100 | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| F | 159 | 1 | 2 | 100 |

| G | 208 | 1 | 3 | 100 |

| H | 252 | 1 | 4 | 100 |

| Increasing Other Inputs | ||||

| I | 100 | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| J | 110 | 1 | 1 | 110 |

| K | 120 | 1 | 1 | 120 |

| L | 130 | 1 | 1 | 130 |

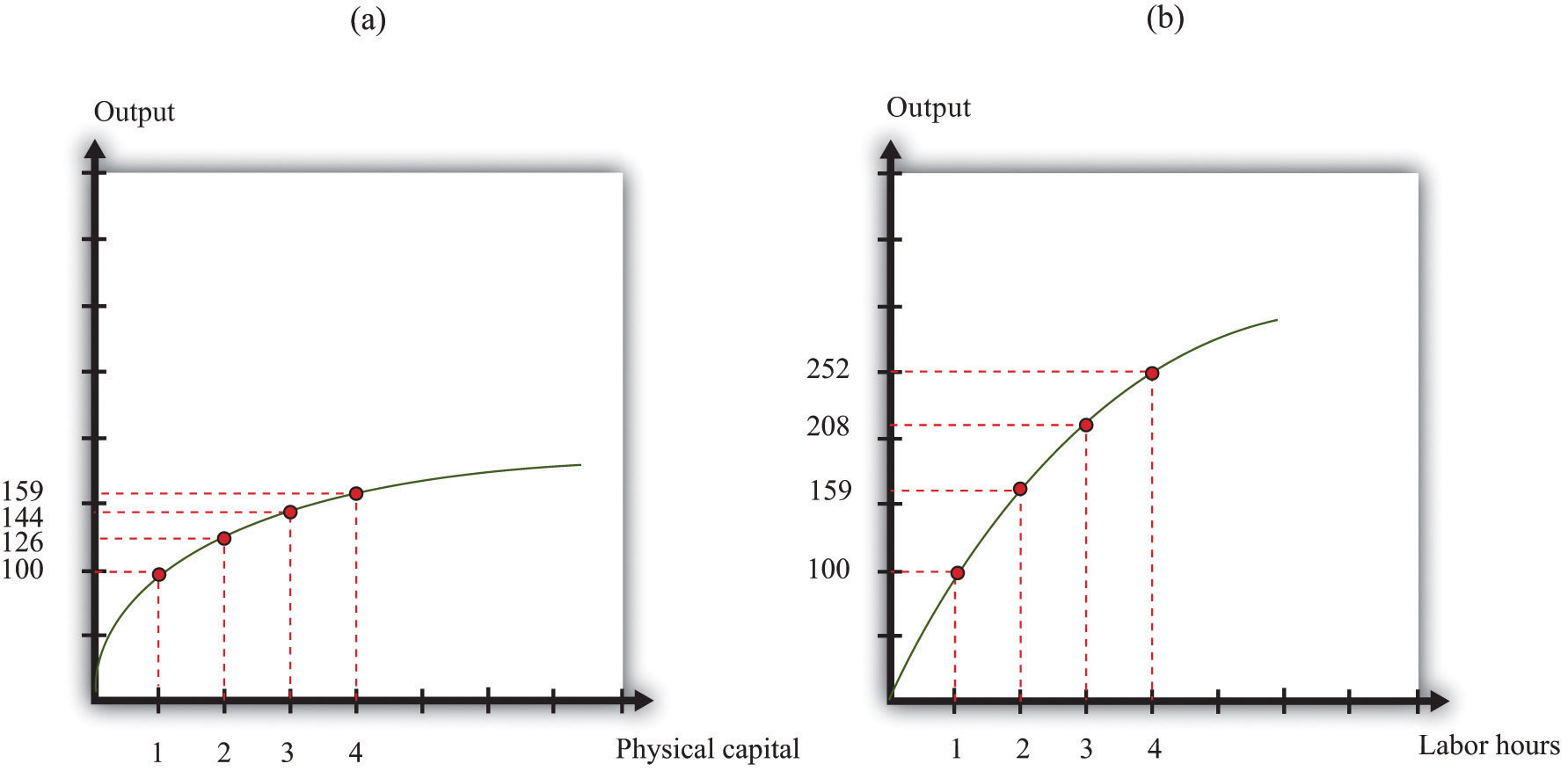

If you compare row A and row B of Table 5.1 "A Numerical Example of a Production Function", you can see that an increase in capital (from 1 unit to 2 units) leads to an increase in output (from 100 units to 126 units). Notice that, in these two rows, all other inputs are unchanged. Going from row B to row C, capital increases by another unit, and output increases from 126 to 144. And going from row C to row D, capital increases from 3 to 4 and output increases from 144 to 159. We see that increases in the amount of capital lead to increases in output. In other words, the marginal product of capital is positive.

Similarly, if you compare rows E–H of Table 5.1 "A Numerical Example of a Production Function", you can see that the marginal product of labor is positive. As labor increases from 1 to 4 units, and we hold all other inputs fixed, output increases from 100 to 252 units. Finally, rows I to L show that increases in other inputs, holding fixed the amount of capital and labor, likewise leads to an increase in output.

Figure 5.3 "A Graphical Illustration of the Aggregate Production Function" illustrates the production function from Table 5.1 "A Numerical Example of a Production Function". Part (a) shows what happens when we increase capital, holding all other inputs fixed. That is, it illustrates rows A–D of Table 5.1 "A Numerical Example of a Production Function". Part (b) shows what happens when we increase labor, holding all other inputs fixed. That is, it illustrates rows E–H of Table 5.1 "A Numerical Example of a Production Function".

Figure 5.3 A Graphical Illustration of the Aggregate Production Function

The aggregate production function shows how the amount of output depends on different inputs. Increases in the amount of physical capital (a) or the number of labor hours (b)—all else being the same—lead to increases in output.

You may have noticed another feature of the production function from Figure 5.3 "A Graphical Illustration of the Aggregate Production Function" and Table 5.1 "A Numerical Example of a Production Function". Look at what happens as the amount of capital increases. Output increases, as we already noted—but by smaller and smaller amounts. Going from 1 unit of capital to 2 yields 26 extra units of output (= 126 − 100). Going from 2 to 3 units of capital yields 18 extra units of output (= 144 − 126). And going from 3 to 4 yields 15 extra units of output (= 159 − 144). The same is true of labor: each additional unit of labor yields less and less additional output. Graphically, we can see that the production function becomes more and more flat as we increase either capital or labor. Economists say that the production function we have drawn exhibits diminishing marginal productThe more an input is being used, the less is its marginal product..

The more physical capital we have, the less additional output we obtain from additional physical capital. As we have more and more capital, other things being equal, additions to our capital stock contribute less and less to output. Economists call this idea diminishing marginal product of capitalThe more physical capital that is being used, the less additional output is obtained from additional physical capital..

The more labor we have, the less additional output we obtain from additional labor. Analogously, this is called diminishing marginal product of laborThe more labor that is being used, the less additional output is obtained from additional labor.. As we have more and more labor, we find that additions to our workforce contribute less and less to output.

Diminishing marginal products are a plausible feature for our production function. They are easiest to understand at the level of an individual firm. Suppose you are gradually introducing new state-of-the-art computers into a business. To start, you would want to give these new machines to the people who could get the most benefit from them—perhaps the scientists and engineers who are working in R&D. Then you might want to give computers to those working on production and logistics. These people would see a smaller increase in productivity. After that, you might give them to those working in the accounting department, who would see a still smaller increase in productivity. Only after those people have been equipped with new computers would you want to start supplying secretarial and administrative staff. And you might save the chief executive officer (CEO) until last.

The best order in which to supply people would, of course, depend on the business. The important point is that you should at all times give computers to those who would benefit from them the most in terms of increased productivity. As the technology penetrates the business, there is less and less additional gain from each new computer.

Diminishing marginal product of labor is also plausible. As firms hire more and more labor—holding fixed the amount of capital and other inputs—we expect that each hour of work will yield less in terms of output. Think of a production process—say, the manufacture of pizzas. Imagine that we have a fixed capital stock (a restaurant with a fixed number of pizza ovens). If we have only a few workers, then we get a lot of extra pizza from a little bit of extra work. As we increase the number of workers, however, we start to find that they begin to get in each others’ way. Moreover, we realize that the amount of pizza we can produce is also limited by the number of pizza ovens we have. Both of these mean that as we increase the hours worked, we should expect to see each additional hour contributing less and less in terms of additional output.

In contrast to capital and labor, we do not necessarily assume that there are diminishing returns to human capital, knowledge, natural resources, or social infrastructure. One reason is that we do not have a natural or obvious measure for human capital or technology, whereas we do for labor and capital (hours of work and capital usage).

Over the last several decades, a host of technological developments has reduced the cost of moving both physical things and intangible information around the world. The lettuce on a sandwich sold in London may well have been flown in from Kenya. A banker in Zurich can transfer funds to a bank in Pretoria with a click of a mouse. People routinely travel to foreign countries for vacation or work. A lawyer in New York can provide advice to a client in Beijing without leaving her office. These are examples of globalizationThe increasing ability of goods, capital, labor, and information to flow among countries.—the increasing ability of goods, capital, labor, and information to flow among countries.

One consequence of globalization is that firms in different countries compete with each other to a much greater degree than in the past. In the 1920s and 1930s, the automobiles produced by Ford Motor Company were almost exclusively sold in the United States, while those produced by Daimler-Benz were sold in Europe. Today, Ford and DaimlerChrysler (formed after the merger of Chrysler and Daimler-Benz in 1998) compete directly for customers in both Europe and the United States—and, of course, they also compete with Japanese manufacturers, Korean manufacturers, and others.

Competition between firms is a familiar idea. Key to this idea of competition is that one firm typically gains at the expense of another. If you buy a hamburger from Burger King instead of McDonald’s, then Burger King is gaining at McDonald’s expense: it is getting the dollars that would instead have gone to McDonald’s. The more successful firm will typically see its production, revenues, and profits all growing.

It is tempting to think that, in a globalized world, nations compete in much the same way that firms compete—to think that one nation’s success must come at another’s expense. Such a view is superficially appealing but incorrect. Suppose, for example, that South Korea becomes better at producing computers. What does this imply for the United States? It does make life harder for US computer manufacturers like Dell Inc. But, at the same time, it means that there is more real income being generated in South Korea, some of which will be spent on US goods. It also means that the cheaper and/or better computers produced in South Korea will be available for US consumers and producers. In fact, we expect growth in South Korea to be beneficial for the United States. We should welcome the success of other countries, not worry about it.

What is the difference between our McDonald’s-Burger King example and our computer example? If lots of people switched to McDonald’s from Burger King, then McDonald’s would become less profitable. It would, in the end, become a smaller company: it would lay off workers, close restaurants, and so on. A company that is unable to compete at all will eventually go bankrupt. But if South Korea becomes better at making computers, the United States doesn’t go bankrupt or even become a significantly smaller economy. It has the same resources (labor, capital, human capital, and technology) as before. Even if Dell closes factories and lays off workers, those workers will then be available for other firms in the economy to hire instead. Other areas of the economy will expand even as Dell contracts.

In that case, do countries compete at all? And if so, then how? The Dubai government’s website that we showed at the beginning of this chapter provides a clue. The website sings the praises of the Emirate as a place for international firms to establish businesses. Dubai is trying to entice firms to set up operations there: in economic language, it wants to attract capital and skilled labor. Dubai is not alone. Many countries engage in similar advertising to attract business. And it is not only countries: regions, such as US states or even cities, deliberately enact policies to influence business location.

Dubai is trying to gain more resources to put into its aggregate production function. If Dubai can attract more capital and skilled labor, then it can produce more output. If it is successful, the extra physical and human capital will lead to Dubai becoming a more prosperous economy.

In the era of globalization, inputs can move from country to country. Labor can move from Poland to the United Kingdom or from Mexico to the United States, for example. Capital can also move. At the beginning of this chapter, we quoted from an article explaining that a Taiwanese manufacturer was planning to open a factory in Vietnam, drawn by low wages and preferential tax treatment. This, then, is the sense in which countries compete with each other—they compete to attract inputs, particularly capital. CompetitivenessThe ability of an economy to attract physical capital. refers to the ability of an economy to attract physical capital.

We have more to say about this later. But we should clear up one common misconception from the beginning. Competing for capital does not mean “competing for jobs.” People worried about globalization often think that if a Taiwanese factory opens a factory in Vietnam instead of at home, there will be higher unemployment in Taiwan. But the number of jobs—and, more generally, the level of employment and unemployment—in an economy does not depend on the amount of available capital.Chapter 8 "Jobs in the Macroeconomy" and Chapter 10 "Understanding the Fed" explain what determines these variables. This does not mean that factory closures are benign. They can be very bad news for the individual workers who are laid off and must seek other jobs. And movements of capital across borders can—as we explain later—have implications for the quality of available jobs and the wages that they pay. But they do not determine the number of jobs available.

Earlier, we observed that our news stories were about the following:

Which input to the production function is being increased in each case?